| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

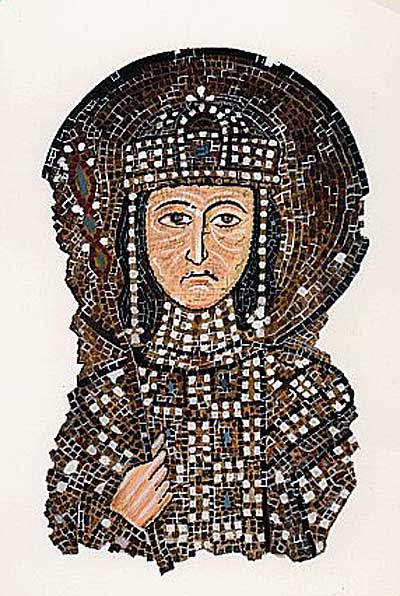

Anna Comnena

1081

Anna Comnena:

The Norman Invasion of Albania

Byzantine historian Anna Comnena (1083- ca. 1153) was the daughter of Emperor Alexius I Comnenus (reg. 1081-1118) and his wife Irene Ducas. In 1097, she married historian Nicephorus Bryennius (1062-1138). The failure of a clumsy plot to prevent her younger brother, John II Comnenus (reg. 1118-1143), from succeeding to the throne, forced her and her mother to retire to a convent. There she spent the rest of her days, devoting her energies to erudition and scholarship. With the death of her husband in 1138, she continued his "History" which, on its completion in 1148 in eight books, became known as the "Alexiad." Of interest in the "Alexiad" which, as the title implies, is devoted to the memory of her father, is her description of the Norman invasion of Albania led by her father's early rival, Robert Guiscard, Duke of Apulia (reg. 1057-1085). Guiscard laid siege to Durrës in 1081 and defeated the Byzantine emperor there. His men then set off in pursuit of Alexius. Anna Comnena describes the events with great clarity.

Robert reached the sanctuary of St Nicolas, where was the imperial tent and all the Roman baggage. He then despatched all his fit men in pursuit of Alexius, while he himself stayed there, gloating over the imminent capture of the enemy. Such were the thoughts that fired his arrogant spirit. His men pursued Alexius with great determination as far as a place called by the natives Kake Pleura [Ndroq]. The situation was as follows: below there flows the River Charzanes [Erzen]; on the other side was a high, overhanging rock. The pursuers caught up with him between these two. They struck at him on the left side with their spears (there were nine of them in all) and forced him to the right. No doubt he would have fallen, had not the sword which he grasped in his right hand rested firmly on the ground. What is more, the spur tip on his left foot caught in the edge of the saddle cloth (which they call a hypostroma) and this made him less liable to fall. He grabbed the horse's mane with his left hand and pulled himself up. It was no doubt some divine power that saved him from his enemies in an unexpected way, for it caused other Kelts to aim their spears at him from the right. The spear points, thrust towards his right side, suddenly straightened him and kept him in equilibrium. It was indeed an extraordinary sight. The enemies on the left strove to push him off; those on the right plunged their spears at his flank, as if in competition with the first group, opposing spear to spear. Thus the emperor was kept upright between them. He settled himself more firmly in the saddle, gripping horse and saddle cloth alike more tightly with his legs. It was at this moment that the horse gave proof of its nobility. Under any circumstances, it was unusually agile and spirited, of exceptional strength, a real warhorse (Alexius had actually acquired him from Bryennius, together with the purple-dyed saddle cloth when he took him prisoner during the reign of Nicephorus Botaniates). To put it shortly, this charger was now spirited by Divine Providence: he suddenly leapt through the air and landed on top of the rock I mentioned before as if he had been raised on wings - or to use the language of mythology, as if he had taken the wings of Pegasus. Bryennius used to call him Sgouritzes (Dark Bay). Some of the barbarians' spears, striking at empty air, fell from their hands; others, which had pierced the emperor's clothing, remained there and were carried off with the horse when he jumped. Alexius quickly cut away these trailing weapons. Despite the terrible dangers in which he found himself, he was not troubled in spirit, nor was he confused in thought; he lost no time in choosing the expedient course and contrary to all expectation escaped from his enemies. The Kelts stood open-mouthed, astonished by what had happened, and indeed it was a most amazing thing. They saw that he was making off in a new direction and followed him once more. When he was a long way ahead of his pursuers he wheeled round and, coming face to face with one of them, drove his spear through the man's chest. He fell at once to the ground, flat on his back. Turning about, Alexius continued on his way. However, he fell in with several Kelts who had been chasing Romans further on. They saw him a long way off and halted in a line, shield to shield, partly to rest their horses, but at the same time hoping to take him alive and present him as a prize of war to Robert. Pursued by enemies from behind and confronted by others, Alexius despaired on his life; but he gathered his wits and noting in the centre of his enemies one man who, from his physical appearance and the flashing brightness of his armour, he thought was Robert, he steadied his horse and charged at him. His opponent also levelled his spear and they both advanced across the intervening space to do battle. The emperor was first to strike, taking careful aim with his spear. The weapon pierced the Kelt's breast and passed through his back. Straightway he fell to the ground mortally wounded, and died on the spot. Thereupon Alexius rode off through the centre of their broken line. The killing of this barbarian had saved him. The man's friends, when they saw him wounded and hurled to the ground, gathered round and tended him as he lay there. The others, pursuing from the rear, meanwhile dismounted from their horses and recognized the dead man. They beat their breasts in grief, for although he was not Robert, he was a distinguished noble, and Robert's right-hand man. While they busied themselves over him, the emperor was well on his way...

After this, the Kelts went on their way to Robert. When the latter saw them empty-handed and learnt what had happened to them, he bitterly censured all of them and one in particular, whom he even threatened to flog, calling him a coward and an ignoramus in war. The fellow expected to be put to horrible torture - because he had not leapt onto the rock with his own horse and either struck and murdered Alexius, or grabbed him and brought him alive to Robert. For this Robert, in other respects the bravest and the most daring of men, was also full of bitterness, swift to anger, with a heart overflowing with wrath. In his dealing with enemies he had one of two objects: either to run through with his spear any man who resisted him, or to do away with himself, cutting the thread of Fate, so to speak. However, the soldier whom he accused now gave a vivid account of the ruggedness and inaccessibility of the rock: no one, he added, whether on foot or on horseback, could climb it without divine aid - not to mention a man at war and engaged in fighting; even without war it was impossible to venture its ascent. "If you can't believe a word I say," he cried, "try it yourself - or let some other knight, however daring, have a go. He will see it's out of the question. Anyway, if someone should conquer that rock, not only minus wings but even with them, then I myself am ready to endure any punishment you'd like to name and to be damned for cowardice." These words, which expressed the man's wonder and amazement, appeased Robert's fury; his anger turned to admiration. As for the emperor, after spending two days and nights in travel through the winding paths of the neighbouring mountains and all that impassable region, he arrived at Achrida [Ohrid]. On the way, he crossed the Charzanes and waited for a short time near a place called Babagora [Krraba mountains between Tirana and Elbasan] a remote valley. Neither the defeat nor any of the other evils of war troubled his mind; he was not worried in the slightest by the pain from his wounded forehead; but in his heart he grieved deeply for those who had fallen in the battle and especially for the men who had fought bravely. Nevertheless, he applied himself wholly to the problems of the city of Dyrrachium [Durrës] and it hurt him to recall that it was now without its leader, Palaeologus (for he had been unable to return - the war had moved so fast). To the best of his ability he ensured the safety of the inhabitants and entrusted the protection of the citadel to the Venetian officers who had migrated there. All the rest of the city was put under the command of Komiskortes, a native of Albania (τῷ ἔξ Αρβανῶν ὁρμωμένῳ), to whom he gave profitable advice for the future in letters.

It was generally agreed and some actually said that Robert was an exceptional leader, quick-witted, of fine appearance, courteous, a clever conversationalist with a loud voice, accessible, of gigantic stature, with hair invariably of the right length and a thick beard; he was always careful to observe the customs of his own race; he preserved to the end the youthful bloom which distinguished his face and indeed his whole body, and was proud of it - he had the physique of a true leader; he treated with respect all his subjects, especially those who were more than usually devoted to him. On the other hand, he was niggardly and grasping in the extreme, a very good businessman, most covetous and full of ambition. Dominated as he was by these traits, he attracted much censure from everyone. Some people blame the emperor for losing his head and starting the war with Robert prematurely. According to them, if he had not provoked Robert too soon, he would have beaten him easily in any case, for Robert was being shot at from all directions, by the Albanians (ἀρβανιτῶν) and by Bodinus' men from Dalmatia. But of course fault-finders stand out of weapon range and the acid darts they fire at the contestants come from their tongues. The truth is that Robert's manliness, his marvellous skill in war and his steadfast spirit are universally recognized. He was an adversary not readily vanquished, a very tough enemy who was more courageous than ever in his hour of defeat.

[Extract from: Anna Comnena, The Alexiad, IV 7-8, Bonn 1836, p. 215‑221 and p. 293-294. Translated from the Greek by E. R. A. Sewter in: The Alexiad of Anna Comnena, London 1969, p. 149‑153 and p. 195. Reprinted in Robert Elsie: Early Albania, a Reader of Historical Texts, 11th-17th Centuries, Wiesbaden 2003, p. 6-9.]

TOP