| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

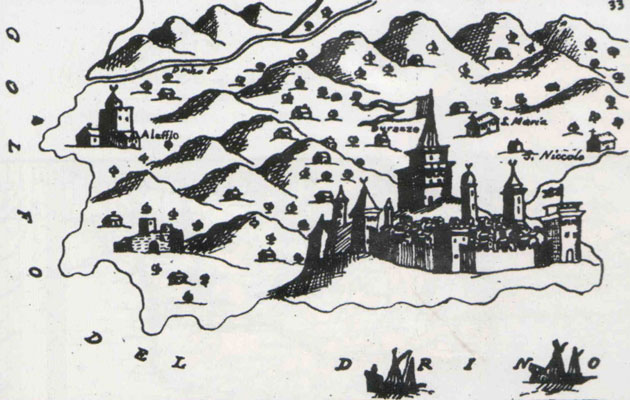

Durrës in a 17th century map

by Vincenzo Maria Coronelli.

1267

George Pachymeres:

An Earthquake in Durrës

Historian and scholar George Pachymeres (1242- ca. 1310) was born in Nicaea and held high office in Constantinople. His 'History' covers the reigns of Michael VIII Palaeologus (r. 1261-1282) and Andronicus II (r. 1282-1328) and constitutes the main source for the period. In it is a moving description of the terrible earthquake which struck the city of Durrës. French historian Alain Ducellier dates the tragic event to July 1267.

After some time, a pitiful and tearful event took place in Durrës. In the course of the month of July, unusual noises caused the earth to tremble continuously, noises which we would normally call a groaning. They portended that something dreadful was about to occur. One day, the din echoed more continuously and more forcefully than it had done previously. The fear which took hold of some people caused them to go and find shelter outside the city, as they were afraid that things would get worse. Night fell upon the groaning din of the previous day and with it, a strong earthquake took place, more violent than any other in living memory. It was not, as one might describe it, a trembling of the earth moving crosswise, but rather a repeated thumping and swaying such that in no time at all, the whole city was turned upside down and was razed to the ground. The houses and tall buildings, resisting not for a second, gave way and tumbled, burying their inhabitants within them. For there was nowhere for the people to escape because the buildings were constructed one beside the other. Indeed, much greater was the chance of survival for those who stayed indoors than for those who ran out of the houses which had been partially spared. None of the buildings survived intact. They collapsed onto one another, and any edifice which happened to have been spared the fate of destruction, was crushed in the collapse of the others. The catastrophe was too sudden and overwhelming to allow anyone to survive by fleeing. For many people, it was like a dream; they never found out in what event they perished. Small children and babies, not understanding what had happened, were buried in the rubble. The din and the tumult were such that the survivors, finding themselves before the frothing surge of the sea, imagined this to be not only the beginning of more agony but indeed the end of the world. As the city was at the seaside and the dreadful quake had taken place so suddenly, those who found themselves outdoors and who had been virtually deafened, confronted as they were by such a tumult and by the din of houses caving in one after the other, could envisage nothing other than the destruction of the entire universe.

The earthquake lasted for quite some time until nothing was left standing. Everything within the city had collapsed and engulfed the inhabitants, with the sole exception of the acropolis which stood fast and survived the quake. When day dawned, the inhabitants of the surrounding area rushed into the city at once and began digging, using everything they could get their hands on: pickaxes, pitchforks and any other tools they could find. Down on all fours, they began excavating, endeavouring of course to rescue any unfortunate victim who might still be alive, but what is more, looking to get their hands on all manner of wealth they could extract from the ruins. As it happened, with the property of the dead, perished the heirs, too, and there was no one left to claim his rightful property. Thus, having burrowed among the ruins for days and, with pitchforks in lieu of sickles, having reaped a harvest of gold, the Albanians and those living nearby eventually abandoned this ancient city to its solitude, a city now only vaguely recognizable, counted among existing cities not for its existence, but simply for its name alone. Its bishop, Nicetas, who had been there at the time, survived, though he was to bear the wounds of the disaster all over his body. At the sight of such a calamity, which no one would ever have thought possible, he panicked and fled, leaving the metropolis deprived not only of his person, but also of its inhabitants, of the splendour of its buildings and of its one-time hustle and bustle.

[Extract from: Georgii Pachymeris: Relationes historicae, Bonn (1835), V. 7, p. 456-461. Translated by Robert Elsie. First published in R. Elsie: Early Albania, a Reader of Historical Texts, 11th - 17th Centuries, Wiesbaden 2003, p. 12-13.]

TOP