| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

Léon Gérôme, "Albanian Smoking Tobacco," Oil Painting (Private Collection, USA).

1610

Marino Bizzi:

Report of a Visit to Parts of Turkey, Bar, Albania and SerbiaMarino Bizzi, originally from the Dalmatian island of Rab, was the Archbishop of Bar (Antivari) from 1608 to 1625. He regarded himself as a bulwark in the defence of the interests of the Vatican in a region which was increasingly leaving the fold of the Catholic Church and converting to Islam. Among his duties was the preparation and transmission to Rome of reports on the state of the church in the regions under his authority. The report of his visit to northern Albania in 1610 is considered one of the most interesting and informative descriptions of northern Albania in the early years of the seventeenth century.

Report of Marino Bizzi, Archbishop of Bar (Antivari),

on his visit to Turkey, Bar, Albania and Serbia in the year 1610... While I was greeting the steward of the sanjak bey, I met a cavalryman from Selita (1) called Musli Bey who, a few months earlier, had met and made good friends in Albania with my nephew Angelo, who had gone there for business on my behalf. The day after my return to Bar (Antivari), he thus came to meet me and to inform me that he had worked for my relative, the secretary of the grand vizier. He also wished to inquire as to whether he could be of any assistance to me, it being that, as he was so fond of that gentleman, he was ready and willing to express towards me the gratitude he felt for that person. When he learned that I was about to undertake a journey to visit the Christians of Albania, he offered to accompany me wherever I should command and, if I were resolved to depart within the next two or three days, he would wait for me.

I accepted the offer to go to Albania under his escort because my nephew had told me of the warm welcome this man had extended to him and, in particular, because the Christians of Bar had recommended him. I was apprehensive simply because many friends of mine had told me that I would come up against a great many perils and would almost certainly lose my own life and that of my relatives. This was because there was a growing Turkish (2) hatred of and insolence towards the Christians. The former have become extremely suspicious since the conquest and looting of Durrës by the Western fleet last year. I was, however, even more uneasy at the thought of not being able to accomplish such a difficult mission and of having to return soon with little to show for myself. The six hundred pieces of gold which His Holiness, Pope Clement, had granted to my predecessor, Monsignor Orsino, for the visit did not seem sufficient for half of the trip and would force me to turn back. Nonetheless, I had my relatives send me money once again, despite the fact that I felt sorry for them since I had spent over two thousand ducats, and ordered, for any eventuality, that more money be sent to Dubrovnik on my behalf. At the beginning of March, I set off in the name of God, blessing the people of Bar and asking them to pray for my well being and that God give me the strength needed to overcome the difficulties ahead so that I could accomplish His holy mission.

That morning we mounted our horses and had just ridden down from the town gate on the Saint Hillary side when the cavalryman, Musli Bey, began with great merriment to demonstrate the capabilities of his steed. With a single shout, he spurred his horse into a gallop along the rocky road which is on the other side of the brook called Orciuli. It galloped with such speed and agility that it seemed not to touch the ground at all. I, for my part, was afraid that the Turk had been too affected by wine to realize that he might injure the horse and break his own neck to boot on that rocky road. We went after him, fearful all the time that the horses would stumble, although we were riding much more slowly. In the meadows along the roadside, he would make his horse prance about on its hind legs despite the fact that the earth was moist from the rain and it was difficult to advance at all without breaking a leg. Often, when we were riding up out of ditches and brooks, without even being back on the path, it would dash up the hillsides like a roebuck. The other cavalrymen and janissaries who were accompanying us to Selita could not resist prancing about with their horses either. They often galloped in twos side by side, embracing one another all the way. They were so nimble and agile that in all their movements, their turbans did not even shift, let alone fall off, although turbans are just as likely to do so as our hats are.

That evening we arrived at Selita, a village of about twenty-five homes inhabited entirely by Turks. We were put up at the home of the aforementioned Musli Bey, in a ground level building with a big front courtyard, though without roofing, as is the custom of the Turks. They care little for convenience and cleanliness in their homes; in fact they despise it. As such, the room we were lodged in had only a few mats on straw as a floor, upon which we sat cross legged, ate and later slept. For me, they brought in a mattress and put it under the mats. There were enough blankets for everyone. At meal times, they brought in a round red Bulgarian hide without any tablecloth or serviette, over which they spread out a striped linen cloth in Moorish colours. The spoons, which all Turks rich and poor possess, were only made of wood, but were very smooth. They do not use any other utensils. They use their fingers instead. Hanging from the walls of that room were all sorts of Turkish weapons. They also kept horses, which were chained to a feeding trough with one hind leg tied to a peg in the ground so that they would remain quiet.

The cavalryman's elderly father lived there. He was grey with age but still robust. In his youth, he had, for certain worldly reasons, reneged on his Christian faith and, as a result, the whole large family, including three able and indeed courageous sons, had become Turks. The cavalryman did everything he could in his home to keep me satisfied and begged me to stay for a few more days. However, as soon as I heard that the old man had turned Turk and had caused the loss of all the souls of that large family, I could hardly wait to get away from there and to depart for Shas, three miles away, which I did in the company of the said cavalryman.

Shas was once a great and well built city, as its ruins still show. It is said that there were once up to 365 churches here, i.e. one for every day of the year. It has now shrunk to the size of a village, a common occurrence under the Turks, who abandon and destroy everything. It used to have a bishop who was one of the electors of Bar. It is situated on the top of a hill, above a large and pleasant lake full of various kinds of fish, off which the inhabitants live. In the winter, the lake is covered by swarms of ducks, swans, herons and other such birds. It is situated twenty miles from Bar. Across from it, towards the sea, is the town of Ulcinj which, during the last war, fell to the Turks together with Bar. The two cities were formerly possessions of the Republic of Venice. It has eighty houses, almost all of which are inhabited by Latin Christians, plus a few Turks. It has a relatively large and spacious church, that of Saint John the Baptist, and a good number of others which have been discovered. The church is very badly furnished. There is no picture above the altar, nothing but a wooden cross. On the walls below the rostrum are the portaits of several saints. It lacks a baptistry and a shrine, as do most of the other churches in Albania. The reason for this, they say, is that it is dangerous to have a baptistry because the Turks might use the water. The resident parish priest is Dom Lawrence Mezilli whom I had sent there several weeks earlier. The inhabitants speak no other languages but Albanian and Turkish. Since the priest's house was at the foot of the hill near the lakeside, I took up lodgings near the church at the home of a Turk called Hasan, who had bought a Christian woman as his wife. Her father had willingly sold her for twenty-five talers.

This woman came up to me and asked me to give her an Agnus Dei medallion free of charge, since we had brought some with us from Rome. I told her right off that she was living in disgrace before God since she had consented to marry an infidel and that it would be preferable if she not approach him at all. If this were not possible, she should at least endeavour not to commit any sins when he approached her, if she wished to save her soul.

Meanwhile, Dom Thomas Armani arrived, chaplain of the village of Saint George (3) on the river Buna, in order to accompany me thither. I confirmed fifty-three souls, carried out other functions and gave my blessing to the people and with that, we sailed across the lake on several vessels hollowed out of whole tree trunks four paces long and less than half a pace wide. These are used on all the inland waterways in Albania. By linking two of these vessels together, even horses, however unruly they may be, can be transported across the rivers. The village of Saint George has about thirty houses, all inhabited by Latin Christians. These people, like the inhabitants of Shas, pay tribute to a cavalryman, who is more or less an army veteran in the sultan's favour. The sultan confers this income upon the cavalryman, and the cavalryman, in return, is obliged, whenever the sultan should so command, to go to war with a quantity of his soldiers and receive no further remuneration. The cavalryman of this village at the time was Isuf Çaushi, who was to die on his way to Constantinople several months later, when I sent my nephew there.

Since the said village, as has been noted, is situated on the river near Lake Shas, it abounds in fish, especially mullet, which lay their eggs there when the time is right. The aforementioned river is as big as the Tiber, and has many fish because it flows out of Lake Shkodra. The lake itself is also full of all kinds of fish, especially mullet, brace and eels of such an unusual size that they exhaust the fishermen who catch them and the seamen who load them onto their boats for export to Apulia, increasing the wealth of the sultan. At certain times of the year, the fishermen sail around the mouth of the river and fill their boats with huge quantities of fish, especially of mullet and varoli that is, if they are not impeded by the waves from pulling in their nets and filling their vessels with the fish.

As soon as we arrived in Saint George, the cavalryman asked my permission to return that night to Selita so that he might tend to his household affairs as he would be away from home for quite some time. He said he would return the next day. I agreed since both he and Dom Thomas assured me that we were being lodged in a safe place. This turned out to be a mistake because, in his absence, a grave incident occurred.

At dawn, on the morning of March 12th, which is the feast of Saint Gregory, a group of twenty-five armed Turks sent by Suleyman Aga and Sinam Rais, the Voyvode of Ulcinj, arrived and began beating at the door while we were all sleeping peacefully in the priest's one story home. I was in a separate little room and the others were lying near the entrance on blankets spread on the ground, as is the Albanian custom. They were mostly sea pirates based in Ulcinj and, since a few days earlier the people of Budva had set fire to their only vessel, they were now marauding the countryside, killing and robbing travellers in this region. We had some premonition that they had been notified [of our presence] and encouraged by the Scorovi, who were looking forward to much booty.

They broke into the house, causing much din and uproar, as is the custom of the Turks, discovered our hosts and asked them who they were, not even giving them time to get dressed. They threatened to tie us up and take us back to Ulcinj. My nephew, however, half dressed as he was, rose quickly to his feet and showed them the patent of the Sultan, unfolding it before their eyes. This seemed to calm them down. Indeed, all the Turks who had seen the document admit to having been overwhelmed by it. It was written magnificently in Arabic script on a golden background, with the Sultan's seal all in gold, into which other colours had been worked. It was also in a large format, unusual for documents of this kind.

Taking it in his hands, Sinam Rais read all the commands it contained, for the adherence of which the Kadi of Bar, who is also the Kadi of Ulcinj, was responsible. Once he had read it aloud, with everyone listening attentively, it looked as if Sinam had decided to leave us alone, both in view of the document and of the letters from Isuf Bey which were shown to him. But since these scoundrels had travelled all night in the hope of booty and did not want to return empty handed, they decided on a more devious course of action. Suleyman Aga began by saying that, since it was not certain that the documents were not forgeries, he would have no choice but to take us all back to Ulcinj with him and then on to Shkodra, alleging that he knew Isuf Bey and would let him decide what was to be done. They then began to cart all our possessions out into the courtyard and force our people outdoors under guard. I was still in my room listening to all the uproar. I rose and got dressed so that the Turks would not break in and seize me half naked. Having finished dressing, I was watching what was going on through the slits in the door, when the priest's mother, who had broken into tears over the event, rushed in to tell me what had taken place. This caused one of the Turks to force his way through the door to see if there was anyone else inside. As the room was completely dark, he groped his way blindly in search of people. I was lucky for, although he touched my back with one of his hands, he withdrew from the room without saying a word, thinking no doubt that he had touched the old woman. Shortly thereafter, when all the Turks and our people were out in the courtyard, the priest came in and asked what was to be done now that we had shown them the Sultan's patent and they had chosen not to respect it. I told him to go out and see what they really wanted from us. He replied that they were a band of thieves who were ready to kill anyone, irrespective of his prince and representatives, and that they had come in search of something to eat. I ordered him to go out and promise them a few zecchini if they would go their way and leave us alone. But the Turks wanted more. Since there were quite a few of them, they did not want to release me until each of them had received his just reward. As such, not only did they take away all our money, aside from a few coins I had sewn into my vest, but Suleyman Aga, finding a jacket belonging to my nephew, which had cost forty scudi, put it on and set off with the others for Ulcinj, leaving all of us stunned and confused. The last one to leave was Sinam Rais, who protested that he had not agreed to such wicked deeds and that he had not taken so much as an asper from the booty. He begged us to bear witness to this fact, should it be necessary.

As soon as the Turks left, the whole courtyard in which we were standing was flooded with armed villagers who had supposedly come to my rescue. They excused themselves by saying that the incident had taken place so early that no one had realized what was going on, except those already at work. This was all nonsense because in actual fact, they had taken great care not to put up any resistance to the Turks (who came to the village daily) in order not to make enemies of them and not to suffer even more from their insolence. The effect of this was to be seen later.

We then went to mass at the church and subsequently dealt with some marital problems, etc. The church is quite small, but is attractive and in good order. It is called St George's and is surrounded by walls painted with the images of saints. Over the main altar is a beautiful Madonna. The church is also furnished with garments and rather decent chalices, but the altar had not been consecrated, as have hardly any of the altars in Albania. I discovered that the portable altar had huge cracks in it and that the priest, lacking in knowledge, was using it to celebrate mass. As such, I gave orders for another slab of stone to be made ready and for the pavement of the church to be cleared of all the stones covering it, for the Albanians are accustomed to placing stones on graves in order to distinguish them. I then returned home.

Outside the church was the cavalryman whom I had called for. Still on his horse, he was listening to what the villagers were reporting about the big robbery. When he approached, he urged me not to take offence as he would make good all the crimes committed by the robbers. Accordingly, after dinner, he mounted his horse and set off with my nephew Marino for Ulcinj to endeavour to ensure the restitution of the goods stolen, or at least to convince a magistrate of the habits of the Turks and to present his case with the magistrate before the Sanjak Bey of Shkodra. I waited at the village for him to return the next day. About ten o'clock at night, a boat or skiff was seen coming down the river from the direction of Samrisht (4) and Shkodra. In it was Dom Theodore Pasquali, Archdeacon of Bar, who, after the archiepiscopal Church of Saint George in Bar had been transformed into a mosque and all of his income had been stolen by the Turks, had taken to ministering in the villages of Mushan and Dajç. (5) His nephew Dom Francis was in Samrisht. Having received word that I had been robbed and since it was not certain that they would not take away what remained, he had come with the sole purpose of persuading me to leave the place and accompany him to Samrisht eight miles away, where I would be safer. Accordingly, I ordered that all my affairs be loaded onto the boat as quickly as possible especially since, on the other side of the river, a little over half a mile away, a group of Turks could be seen coming across the plain towards Saint George. But our people were not quick enough.

The moment we departed, an arquebus shot landed in the village, fired by the Turks who had already reached the other bank with their Algerian arquebuses. There were seven of them and they immediately began shouting from the bank. At the same time, on the opposite side of the river, over twenty Turkish archers from Ulcinj were approaching the village itself. The first seven were getting into a boat. We thought at first that they were trying to reach the other bank, but once they were on board, they sailed down the river and forced us to land, even though we had travelled, quite without defence, over a mile from the village. Joined by the Turks from the other side who had come after us, too, they unloaded all our affairs and then forced us, travellers and crew, to disembark. The latter, being from Budva and friends of one of the Turks called Safer, were released. Also released was Dom Thomas and the Archdeacon, but they refused to abandon us for fear that the scoundrels might take some sinister decision with respect to us. By staying with us, they hoped to save us from death. As soon as we were on land, the Turks began rummaging through our pockets to see whether we had any money or valuables. I indeed had a few gold coins sewn into the lining of my coat and a few jewels in my left pocket which I carried with me for an emergency. Thank God that the Turks did not find them, because although they put their hands into my right pocket, they did not carry their search through to the end. Seizing all our belongings, the Turks set off for Ulcinj, crossing through a lowland forest and taking all of us with them.

I was convinced that we were lost, even though I was a subject of the Lords of Venice and was travelling in the region with patents from the Sultan and Isuf Bey. Since we had the documents with us, I showed them to the Turks, insisting that we were on our way to Shkodra at the invitation of Isuf Bey, to take him some presents. I indeed begged them to consider that he would not be pleased at the tribulations we were going through. Nor would the Porte in Constantinople be pleased since we were the friends of some powerful figures who would be infuriated by our deaths, which would most certainly be avenged in a terrible manner. At the same time, the Archdeacon and Dom Thomas kept on insisting that I was related to Mahmut, the secretary of the grand vizier, and that I was on my way to meet him in Constantinople. They reacted as if they did not believe us or simply did not care. Indeed, one of their leaders said to me that they intended to take us all to Durrës and sell us. By now it was about 11 P.M. and we were getting close to the edge of the forest. I approached the priests and told them I strongly suspected that once we entered the forest, the barbarians would slit our throats, since it had grown dark. I was all the more terrified because I had overheard the Turks tell the local people to pray for us and not to proceed any farther. Indeed one of the villagers who was accompanying us turned back, and my nephew Angelo managed to understand a bit of what they were saying in Turkish, this being to the effect that they intended to kill us all. I therefore told them to try to calm the Turks down by giving them something to eat. I was more than glad to give them everything we owned simply to save our lives.

At this point, the Archdeacon lost control of himself and could not hold back his tears in view of the danger we were facing of losing our lives. This caused me great distress and I now realized I was lost, since the one person who knew the country and the customs of the barbarians had abandoned all hope. For this reason, as we were advancing, I fell slightly behind with Dom George, my chaplain, in order to talk to him before we entered the forest. Ordering him to hide in the hedges and begging him to pray to God for our souls if he should hear that we had been slain, I then hurried forward, hoping that the Turks would not miss him. He, however, instead of following my instructions, stood still, confused and dumbfounded, right in the middle of the road, looking backwards in a daze and not moving from the spot. When one of the Turks happened to look back and saw him in the middle of the road at quite a distance from us, he began shouting and loaded his arquebus to rush back and kill him. Realizing what he intended to do, I ran up to him immediately and managed, with great difficulty, to calm him down, insisting that the chaplain was not trying to escape, but was simply relieving himself. The chaplain then ran up towards us as quickly as he could and caught up with the others.

In the meanwhile, Dom Thomas had been talking to the barbarians to calm them down, in particular to Safer, to whom the crew of the boat had pleaded on our behalf, and to the other leaders. Although I was unaware of the fact because I had not had time to speak to him, he had come to the following agreement with the Turks. They were to take part of our possessions, leaving us free to return to Saint George. We had already entered the forest when I saw the Turks stop and dump all our things onto the ground. One of their leaders ordered me to sit down on a chest. When I saw him take out his scimitar to chop off my head, I dissimulated my fear and replied that I was so exhausted that I did not care to sit down. I simply begged him to reconsider what I had told him earlier on the road. While everyone else was standing around pallid with fear and trepidation, he turned to me and told me to ensure that all of my things were there because he wanted to take only what Dom Thomas had promised him. We were to be allowed to take whatever was left over and depart for wherever we wanted. But first of all, I was to open up the chest because they wanted the money in it. I replied that I would be quite happy for them to take whatever they wanted, including all the money they could find, but that there was not a penny in the chest since they had already taken all of my money that morning. I added that I could not open the chest because I did not have the keys with me as they were with my nephew, but that, if they wanted, they could break the chest open and I would willingly die if they did find any money in it.

They seemed satisfied with this answer and did not break the chest open. Instead, they seized all my most valuable possessions, left us in the forest and continued their journey to Reç (6), a nearby village, to spend the night. As the sun had already set, we decided to gather all our remaining affairs and set off slowly towards Saint George until we could find someone to help us and take us in, thanking God that we had been saved from the hands of the barbarians with less loss than we had expected.

As soon as we arrived at the village, I had a barque made ready and, without any further delay, we sailed up the river Buna in silence and in the dark of night towards Samrisht, leaving Dom Thomas behind to bring with him the affairs which our boat could not hold. I gave instructions for someone to set off immediately for Ulcinj to inform my nephew and the cavalryman about the second attack we had suffered. The priest did send a messenger, but the information did not arrive because the messenger simply pretended to go, and did not transmit the message at all. Most of the people are dishonest, or are afraid of incurring the wrath of the robbers.

In Samrisht, we found the aforementioned Dom Francis Pasquali who was ministering in Gorica across the river. That night we recovered somewhat from the ordeal we had suffered. The next morning I visited the church across the river, which was well-built and capable of holding five hundred souls. It was beautifully adorned with pictures on all sides. It is named after the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin and is well furnished with chalices and ecclesiastical garments, with a small portable altar but, like most churches in Albania, is without a baptistry and shrine, and is badly paved because of all the gravestones. After announcing that we would be confirming the next morning, we returned home to find my nephew and the cavalryman who had come back from Ulcinj. They had only managed to bring with them the jacket because the cavalryman insisted it was his. Since they were not able to get any money, they brought with them a sealed document, being a record of the theft. This, however, was in Turkish and in Turkish script, and turned out to be a simple passport.

We sent messengers to Shkodra immediately with some presents for Isuf Bey in order to inform him of the act of vandalism carried out against me under his sway and, as such, to urge him to repair the injustice committed by having the stolen goods returned to me. The messengers came back and told me that he had expressed such sorrow at the damage inflicted upon me and had reacted to the affront by stating that the violence had been perpetrated against himself and not against me. I was not to worry because he had summoned the leaders of the band and would ensure that everything be returned to me, even if he had to pay for it out of his own pocket. With them came Sinam Rais whom they thought had been staying with Isuf Bey. This was no more than an alibi, since he had been in the company of the thieves.

A little later we received word that the Sanjak Bey of Shkodra, Cascapan, was to arrive at Selita that night on his way to his residence in Shkodra. We then received another message to the effect that an emissary of the schismatic (7) Patriarch of Peja (Pec) had arrived with a group of Turks at the aforementioned Church of the Annunciation across the river in order, as usual, to extort dues from the priests of the Latin villages, dues which, according to an old tradition approved by the Sultans, belonged to the Archbishop of Bar. These dues consisted of two aspers per household annually, twelve for every marriage, twenty-two for the marriage of a widower and forty-eight for the marriage of a widow, as well as one zecchino annually for every church. These emissaries showed up two or three times a year, sometimes, as men-tioned, with the patriarch himself. With the help of the Turks he had with him, he was also extorting dues from the Latins, even though the latter are subjects of the archbishops of Bar alone.

Sinam Rais who, as mentioned above, was the voyvode of Ulcinj and the kadi of the surrounding villages, sent some of his men to bring the emissary before us in order to find out by what authority he was going about extorting from the Latins dues which did not belong to him, and in order to get back everything he had taken, and therewith reward Sinam Rais. When the emissary was brought forth, he presented several imperial patents, by the authority of which he alleged he had the right to go about demanding dues since the sultan had authorized his patriarch to do so. When Sinam read the document, he turned to the emissary and asked him if he did not have any higher authority. When the emissary replied that the patents he had were quite sufficient, Sinam lost his temper and said, "With this patent only, you have been going about, forcibly extorting money from Latins who have nothing to do with your patriarch because they are subjects of the Archbishop of Bar and not of him!" He then ordered the emissary to be tied up and placed under arrest until the sanjak bey arrived. While the guards were busy carrying out the order and bringing forth ropes to tie him up, I said that, since the matter was in my interests, I would be quite satisfied if the emissary, without being tied up, would be brought before the sanjak bey so that the matter could be solved by justice. He should go before the sanjak bey and show him the patents, explaining his reasons, and I would explain my reasons. Sinam and the cavalryman, Musli Bey, accompanied by my nephew, then took the emissary with them and set off for Selita. The few Turks who were still with the emissary abandoned him because they were afraid the sanjak bey might be angry with them. The emissary gave the guards ten talers, promising that he would appear in Shkodra on the following Sunday to resolve the matter in the presence of Isuf Bey. But he did not show up. Several of my priests, for their part, had gone there to protest that they were being forced to pay such dues two or three times a years, even though they owed nothing to the schismatics, but only to their superior, the Archbishop of Bar. And although Isuf Bey ordered that the emissary be summoned once again, he did not show up, but endeavoured even more fervently, with the help of his Turks, to collect what he had not yet managed to obtain. This forced me not to demand fees of anyone because they had already been obliged to pay them elsewhere. I only took what the people gave me voluntarily. This I could not help but accept because I was in a difficult financial situation in view of the theft and the many excessive gifts I had been forced to give to the Turks.

After carrying out our functions in Samrisht and Gorica and leaving orders that prayers be said for the spiritual well being of the souls there, we carried on to Mushan and Dajç where the aforementioned Archdeacon was serving. The next morning we went to visit a church two miles from the village. Because of the distance involved, the village priest often set up an altar in the shelter of his own house to accommodate the people and celebrated mass there when it was muddy and rainy out. I saw them doing this all over Albania where the churches are at a distance. I could not order even chapels, much less churches to be built in the villages because the Turks would not allow any new buildings of this kind. They would not even allow restoration work without being paid.

The aforementioned church bears the name of Saint Nicholas, is well built and can hold five hundred people, but it is very dark and sombre even though comparatively well-furnished with garments and chalices. As usual, it has an uneven stone flooring on unequal and unordered gravestones. Mass is celebrated on a small portable altar, very clean and nice looking, but on close inspection, it was seen to be fractured crosswise. As such, it was necessary to send people to Gorica to fetch the little altar at the church there so that we could celebrate mass that morning, as a large congregation had gathered. But we received no altar from Gorica as the priest could not find it. Other people were therefore sent to the Abbey of Shirq, five or six miles away, i.e. a little over an hour's travel, and brought a small altar back with them. Mass was then celebrated, prayers were said for the dead, and the graves were visited. The people there were very much consoled.

From that church, which is situated on the top of a hill, one can see the fortress of Shkodra about eight miles in the distance on an invincible mass of rock which domi-nates all the surrounding villages and the lake.

When we returned to the village, we confirmed one hundred fifty or more people. Then, we carried on to the church of Shirq and visited three villages in Trush where Dom James Cressendeli and Dom Athanasius Vassi were serving as chaplains. The poll tax from these villages was collected by three brothers, the aforementioned Isuf Bey, Suleyman Aga and Ibrahim Aga, all important and highly respected persons in this region. It happened that we were to call upon the latter two, since Isuf Bey himself was in Shkodra on business. When we came to speak of the robbery which the thieves from Ulcinj had perpetrated against me, the two replied favourably, saying that they would see to it that everything was returned to me, even if they had to pay for it out of their own pockets. But nothing ever came of their promises. I do not know whether this is more because of the lack of sincerity with which the Turks treat the Christians or because they needed to maintain good relations with the Turks of Ulcinj in view of their hostile relations with Isuf Çaushi, timar holder of Shas and Saint George, and with Mustafa Çelebia, revenue collector of Zadrima, with whom they had had a big altercation which caused much grief to the Christians of Zadrima before I set off in that direction.

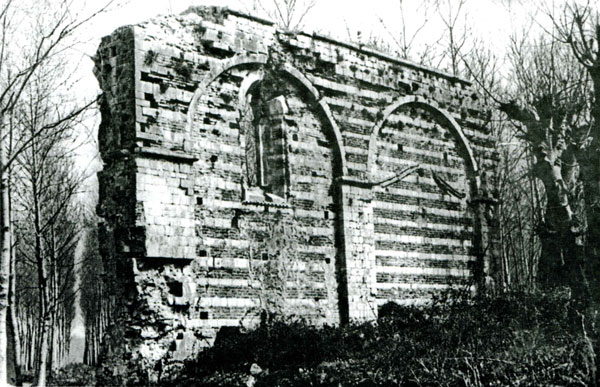

The three villages of Trush have no other church than that of Shirq, two miles away. It is, however, a magnificent structure capable of holding some three thousand people. In the past, Benedictine monks used to live there with substantial income, which the Turks have now got their hands on. The church itself has been damaged by them, as they have removed and broken the best slabs of marble and have gouged out the eyes of all the faces of the saints, with the exception of Saint George and Saint Michael whom they hold in some veneration. As I had been informed that the church had been the object of much impiety, I reconsecrated it. The inhabitants came and brought me half the sum necessary. For the remainder, they asked me to wait, because the three villages had been in conflict with one another as a result of fighting and murders which had occurred when they were finishing the roof of the church. The men from one of the three villages decided, as a result of this, to reduce their contribution to the fraternity and in particular their part in the great amount needed for the feast of Saint Serge, during which food is cooked to be distributed to all the people who come and take part in the feast. The others, without whose consent the decision had been taken, did not agree. As such, they told the priests simply to say mass and hold the feast in the village. This way, no one would have a reason to go to church that day and cause further expenses. But since they were in the minority, they were outvoted by the others who wanted to go to church and do so according to custom, taking Dom Athanasius with them to say mass, since Dom James had refused to go.

When the feast was over that evening, they all departed in a good mood, wanting to pass through the third village which had refused to take part. Some of those who seemed to have been upset by the matter began to insult the other side verbally. They were also angry at the priest, who had gone to celebrate mass against their wishes, and were infuriated in particular when they heard a woman complain about one of them who had shot and killed a chicken with an arrow. They believed this had been done with the expressed purpose of angering them. The altercation progressed from words to deeds involving the arms they were bearing. As such, aside from a good number of wounds on both sides, several people from the third village met their deaths. The one who was accused most for all of this was the priest, who had gone to the church that morning to say mass. A number of the elders thus came forth to ask that he be punished, saying that he had been the first person to raised his hand and shoot five or six arrows. I replied that as soon as my secretary got back from Samrisht, the case could be tried with witnesses, because I did not want to leave the matter unsettled. The priest suddenly turned to Ibrahim Aga, one of his superiors, who appealed to me in no uncertain terms not to try him and not to hold any grudge against him, for he was certain that they were accusing him not because he bore any guilt, but out of pure malevolence and that the priest had only wanted to clarify the matter. He also stated that, since the priest was a relation of his, any action taken against the priest would be considered an action against him, too. I replied that I would gladly do anything I could to please him and that I would be happier if they did not raise the matter and did not bring forth witnesses. But if, on the other hand, they insisted on proceeding, I could not deny them their right to justice, as I was compelled to act accordingly by Christian institutions. He then put the rayah of that village under such pressure that they did not raise the matter again, even though I stayed there among them for almost a week. On this occasion, I asked the aforementioned Ibrahim Aga and his brother Suleyman to intervene between the villages, and the matter was solved within a month.

As such, I had Dom Peter Izi, abbot of Saint Paul's and student of the Clementine College, begin preaching in that language. He had come to accompany me in the region and had been fishing for souls throughout it with the word of God. When we finished baptizing and carrying out other essential activities, we decided to carry on to Barbullush. But since we had a large retinue and much baggage, difficulties with the horses, and since the Turks were looking upon our load of goods with evil intent, I felt it appropriate to send the chaplain, Dom George, and others of the family with almost all the baggage back to Budva, with the exception of what we needed for the journey. I had them accompanied to the river Buna where they boarded a boat for Budva, sailing to the mouth of the river and out to sea to continue their journey. Since it was a large and fully-laden boat and there was little water in the river, they had to stay put for several days before they were able to leave. At that point, the Turks of Ulcinj, who had reasoned or had been informed that I was sending much of the baggage back to Budva on that boat, made their way forthwith and, boarding the vessel, began searching it. Although much of the luggage was hidden under bails of wool with which the boat was laden, they discovered it and carried it all off with them, with the exception of a cross full of relics which had been stored in a safe belonging to the owner of the vessel. Dom George and the others barely escaped into a nearby forest. They were able to take nothing with them but a silver covered mitre with gold bands and a copper cross covered in silver and gold. Isuf Bey had given us nothing but vain promises and words, in the faith of which I believed longer than I should have, and without any result. All the while, I had been striking the iron while it was hot with continuous gifts and had not dared to appeal to the new sanjak bey of Shkodra in order not to anger the said Isuf Bey, under whose authority the people of Ulcinj were said to be.

Thus, as mentioned above, after having our luggage and some of our retinue returned, we advanced quickly from Trush to Barbullush which is situated on the banks of the Drin, a river larger than the Tiber. This river flows with many bends down from Lake Ohrid, dividing the northern part of Albania from Serbia, and passes through the region of Zadrima to arrive in Lezha where it separates into two branches and flows into the Adriatic Sea, forming on its way an island composed of all sorts of trees. Here I came upon Dom Nicholas Gramshi who had been conferred with that parish by the Bishop of Sapa. He was one of the suffragans of Bar. The parish was, however, beyond the border of his diocese, being situated in the diocese of Shkodra. I therefore decided to remove it from the diocese, in particular since the afore-mentioned Ibrahim and Suleyman with their local timariots had asked me to install some priests recommended by them. But finally, upon my return from Rodon and Durrës, after much imploring from the Christians there, who had also turned to Isuf Bey, I restored it once again to the diocese there and made another patent for it.

In Barbullush there is a church of Saint Stephen encompassing 300 souls, with a chalice, paten, a silver cross, but badly paved as usual. There I met the afore-mentioned Bishop of Sapa, Monsignor Nicholas Bardhi, a prelate of good and healthy manners who came out to meet me, as his diocese borders on Barbullush and is separated only by the Drin. On this side of the river, one enters into Zadrima, which is ancient Pharsalia where the battle which pitted Caesar against Pompey took place between Shkodra and Lezha. It is as fertile and pleasant a countryside as one can find in Albania, blessed with a sublime nature and all good things.

Once we had finished our duties in Barbullush, we crossed over the Drin and spent the night in Gjadër, a village with about eighty houses, all inhabited by Christians and with only two or three Turkish houses. Among the latter was Ferat Aga, also known as Cotus (8), meaning the enraged, because the Turks said whenever they had seen him enter battle it was as if he had gone berserk, beating his breast heroically. I paid him a visit and, as usual, took presents with me because my predecessor, Monsignor Orsino, having returned from Serbia, had not treated him in the proper manner and given him the presents he expected. He had therefore been imprisoned and the local Christians had then had great difficulty in getting him released. Nonetheless, the aforementioned abbot, who at the time was in conflict with Muslim Bey, my cavalryman, brought the matter up because Ferat Aga had got his hands on my nephew's jacket which he had taken from the Turks of Ulcinj and put on immediately. He wore it demonstratively, making things worse and trying to play for time although he had been asked on several occasions to give it back. The next morning, however, he left for Shkodra, pretending that he wanted to deal with the business of the Serbian priest. I never saw him again because he was later conscripted into the Persian war and set off with the jacket, as is the custom of the Turks, since they neither keep their word nor respect the law.

From Gjadër we continued on to Blinisht, a village of over two hundred houses, without a single Turk. They pay their poll tax to Mustafa Çelebia of the region, whom we mentioned earlier, amounting to 14,000 talers of income, of which he is obliged to remit 2,000 for some hospitals in Constantinople. He is a man of good and humane behaviour and does good deeds which the Christians do not cease to praise. I went to his home three or four miles away to pay him a visit and offered him the customary presents. I found him seated at a table with over twenty high ranking Turks. After offering me a seat, he invited me several times to dine with them as the table was covered with meat and poultry. I informed him, however, that according to the rules of our faith, we abstained from such foods for 46 consecutive days, during which we fast, and that we were in precisely that period. He told me he was surprised that I was not going to Constantinople to meet Mahmut, the secretary of the grand vizier, to whom, he had been informed, I was closely related, because Mahmut was a highly respected individual and had influence at the Court. He also informed me of the offices and titles he had held up to then and that he would be named Sea Admiral as soon as changes were made in the profession. He concluded by saying that if I should decide to go, he would be glad to accompany me because he would been going in that direction in sixteen days. I replied that I was honoured by his offer and would let him know.

In Blinisht was chaplain Primus Izi who also served in the village of Gjadër. When I passed through, the elders of the village implored me to assign to them a chaplain of their own since Dom Primus was not in a position to serve both places. They proposed Dom Peter Izi, abbot of Saint Paul's. Nonetheless, since the two villages jointly used the church of Saint Stephen, which is situated near Blinisht, and since the inhabitants of this village asserted that they had furnished it with garments, chalices and other necessities, it was uncertain as to whether the priest of Gjadër would have been able to use it without difficulties and expenses. With the intervention and indeed the authority of the bishop, we thus gave satisfaction to both priests and charged both of them jointly, and in this manner, the two villages were satisfied.

As the feast of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin was approaching, I was invited to Lezha, five or six miles from Blinisht, to take part. The feast was celebrated there by a multitude of people in a splendid church capable of holding over two thousand persons, situated outside the town in the direction of the river Drin. The feast was officiated by the Franciscan brothers who have a monastery inhabited by three or four members of their order. They are poor and wretched individuals, having suffered from continuous attacks by the Turks who eat up everything they have. In the aforementioned church, they claim that the famed Alexander Castrioto, also called Scanderbeg, lies buried. He is remembered for his many valiant deeds against the Turks, which have been committed to verse and are sung by all the Albanians in that language, even in the presence of the Turks themselves.

On my arrival in Lezha, I went as usual to visit the kadi of the town to present him with gifts. I showed him my patent from the sultan and he, for his part, prepared another one for me, thus allowing me to travel freely throughout the territory under his jurisdiction.

In past years, Lezha had been something to see, but now it was so much reduced both in buildings and inhabitants that it was almost like a village with the surrounding walls fallen in and with a good proportion of the houses in ruins and reduced to nothing. It is inhabited by Turks who are more insolent here than anywhere else. But it has a fortress on top of a hill which guards and dominates the town.

There are about 30 Christian homes which, for the most part, were hostile towards their bishop, Monsignor Innocent Stoilino, a monk from Dubrovnik and one of the suffragans of Bar, because he had written some unfavourable reports about these poor Christians to Pope Clement VIII and had accused them of being evil tongued and disgusting in appearance. On more than one occasion I had admonished him, though in vain, to move to his residence here from Dubrovnik where he was staying and where I finally encountered him on my return from Serbia. He reacted coldly towards me because I had informed Rome that he was not residing where he should.

At any rate, we celebrated the aforementioned feast in which a surprising number of Christians from the surrounding area came to take part, bringing with them many Turks who entered the church out of curiosity to witness our celebration of mass. There, in the presence of everyone, and in particular of the vicar who was the head of the brothers, I celebrated mass in the most solemn robes I could find, the celebration being attended by many priests and friars who had come from all the villages of the region.

From there, we set off for Balldren, a village of some fifty homes. Dom Andrew Julsi, a native of the area, was serving there at the church of Saint Anne. He had chalices and decent clothes at his disposal. There is a rectangular bell tower, but without a bell. The inhabitants are all Catholic Christians, with the exception of two homes of Turks.

We then went on to Kakarriq which, since it is a village of 160 homes, has two priests: Dom Christopher Krytha and Dom John of Nica. It also has a church of Saint Nicholas with a rectangular bell tower complete with bell. There were no Turks. We then proceeded to Kukël on the same side of the Drin, half of which is in the diocese of Shkodra and the other half in that of Lezha. There I had happened on Isuf Bey with his brother and a large company of Turks who had just come back from a holiday at the house of Teta Midha, one of the leaders of that region. On this occasion I went to visit him to see if any decision had been taken regarding the restitution of the goods stolen by the men of Ulcinj. He offered his apologies, saying that he had not had an opportunity to talk to them because a number of things had got in the way, but that as soon as he found the time, he would do everything in his power to see that the goods were returned to me. From this reply, slightly different from the earlier ones, I realized that it was a waste of time to pursue the matter any further. His words were only designed to exhaust me. And this turned out to be the truth since a little later, I was informed that he had got his hands on part of the booty himself. Among other things, a beautifully ornate bedspread made of silk was seen in his home, the one which the thieves had stolen from Dom George at the time.

It so happened that I had breakfast with him one morning when my nephew was present. Halfway through the meal, he invited the abbot and Dom Primus Izi to have a seat, the two of them having come to accompany me. He sat on the floor on a rug made of a skin which looked like it was covered in weasel hair, and wore a great turban on his head. He was an attractive, noble looking man, eloquent and exceptionally courteous.

When we returned to Blinisht that evening, we were visited by the aforementioned Bishop of Sapa with all the priests of that diocese who had come to invite me to bless the holy oils in his church of Saint George, four or five miles away. He refused to do this himself because, knowing that I was there, he regarded it as my duty. I thought it a good idea to satisfy his request because I very much liked and respected him for his good qualities. As he had invited me to visit his diocese before I went any farther, I promised to satisfy his wish as soon as I had returned from Renc on the coast, where the church of Saint John had been desecrated. Some of the old people had come to me on various occasions to beg me to go there and reconsecrate it.

Before leaving the bishop, I decided it was the time and right moment to pay a visit to the kadi of Zadrima since he was not far away from there at the village of Mjeda. While the horses were being made ready on the morning of Good Friday, a number of Turks rode into the bishop's courtyard and declared that the kadi was particularly dissatisfied with him because the Christian archbishop of the region had arrived in Zadrima and had paid the bishop a visit without taking care to present himself and show his esteem to the kadi. We replied, asking them to inform him that at that very moment we were saddling the horses to go and fulfil our obligations towards him. But the Turks refused to depart before we were all on our way. The bishop, apprehensive that some misfortune might occur, took two pairs of roosters and a number of other things with him, in addition to the gifts which I had brought with me, in order to better placate the barbarian.

It was the morning of Good Friday and we were expected for services at the church of Joseph Bardhi, chaplain of Saint Mary's in Glina, which is situated on the road to Mjeda. As soon as we had approached the church, we asked two Turks to ride ahead and inform the kadi that we were on our way so that he would not be angry when we arrived.

I sent the family back to Blinisht and, when the church service was over, only I, the bishop, the abbot and some companions set off on foot. We were accompanied in case of trouble by a good number of elders from the surrounding villages of Hajmel and Renc (9). We soon arrived at the home of the kadi in Mjeda. He was wearing a large turban on his head and was sitting on a bed which resembled a theatre loge three hands above the ground. Seated on rugs and cushions, he was a good looking man with a long black beard. He sprang to his feet to greet me when I entered the room. I was informed that kadis usually do this only for sanjak beys and high level dignitaries. He welcomed me cordially and gave me a seat on some cushions beside him. I apologized for having spent several days in Zadrima without having come to fulfil my obligations towards him. I told him that I had come late because I was hoping to recover the things which the men of Ulcinj had taken from me and, had I had them, I would not have been ashamed to visit him right away since I would have had gifts commensurate with his status. I now hoped at any rate that he would accept my best wishes, together with the humble gifts. Aside from the gifts, I also gave him some money so that he would grant me a passport in accordance with the patent of the sultan. He read out the patent and the other documents I had brought with me and responded that, as soon as his secretary arrived, he would have the passport readied and brought to Blinisht. He expressed his wish to provide me with greater services because of the esteem in which he held Mahmut, the secretary of the grand vizier . He also asked the bishop to sit down across from him, while all the others remained standing. After talking for a while, we begged leave of him and went for lunch with the aforementioned Dom John, who was the nephew of the bishop. There we stayed until late and then mounted our horses once again. The bishop came out and accompanied me almost half the way to Blinisht. As it was already growing dark, I spurred my horse into a gallop so as not to be crossing the plain at night in the land of the Turk. This caused the sword which the abbot was carrying at his side to beat and cut its way into the bottom of the sheath where the patents of the sultan and other things were being kept, because he had attached them to his belt, together with the sword. As such, everything fell out of the sheath and onto the ground without our seeing it, and we arrived in Blinisht without the documents. Not only did we encounter our retinue there half petrified by our late return from the kadi, fearful that something might have happened, but we ourselves were also horrified at the loss of the patents. Although the first two hours of night had already passed, I therefore sent my nephew and the abbot back along the road immediately to see if they could find the things. And thank God, with the little bit of moonlight there was, they discovered everything a little over two miles away and we rendered thanks to the greatness of God that He had helped us out of this predicament.

We celebrated Easter in Blinisht and were witness to the great devotion of the people there. I was very comforted by them when I heard them all in the procession seeking God's mercy and continually repeating and responding to one another in two choirs, 'Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison', both the men, the women and all the children. They are a people with a genuine inclination to spiritual devotion. When they enter a church, they first of all fall upon their knees to say prayers in front of the doorway. As a general rule, none of them eat anything on Fridays throughout the year except eggs and dairy products. When they see a priest pass by, they abandon everything and rush to kiss his hand. At mass, when they hear the word 'Jesus', they all bow and repeat 'Jesus', and observe many other acts of devotion.

I then left to reconsecrate the aforementioned church of Saint John the Baptist of Renc, which is over two miles away from a very large port protected from all the winds. The port takes its name from the aforementioned church, surnamed Medua. Here, upon our arrival, several boats from Budva and Perast fired off artillery to salute us. Because the people of Renc were dissatisfied with their chaplain, Dom Christopher Krytha, who was wont to go there from time to time to say mass and to minister the sacraments, they turned to me, and I assigned Dom Andrew of nearby Balldren because, as they were a poor community, they were unable to maintain a chaplain of their own, even if one could have been found.

In the meanwhile, the time for the aforementioned revenue collector to depart for Constantinople was approaching and I resolved to send with him my nephew Marino to see if he could recover from the Turks the possessions and income of the archbishop and of the other churches of Bar because, in contradiction to agreements made, they had been stolen when the town fell. I also wanted to ensure that my Catholic subjects would not be troubled any further by illegal extortions on the part of the schismatic Serbian patriarch, in addition to confirming my reputation as a subject of the aforementioned pasha so that we would be better treated by the Turks wherever we chose to go. Thus, on the first day of May, when the revenue collector had assured himself of his authority over Zadrima by means of reconciliation with his enemy, Isuf Bey, strengthening this friendship even further by having breakfast with him in his garden in Gramsh, he set off on his journey, accompanied by over thirty horses. I waited for him in Blinisht which he was to pass through to pick up my nephew, for whom I had found a good horse for this long journey. I also wanted to give him some letters for the Bailie of Venice and for his page called Pervana who was trying to get into one of their schools in Constantinople.

When he arrived, he stopped and willingly took with him the letters. As he picked up my nephew, he told me not to worry about him because he would look after him as if he were one of his best friends, and immediately assigned the aforementioned page to look after him exclusively. Once they departed, I was told that when the Turks mount their horses for such a long journey, they hate to be stopped on their way during the first day. If this does happen, they are wont to return home and remount their horses in order to avoid bad luck. He nonetheless journeyed on towards Lezha where they spent the night in a tent. Also with him was the aforementioned archdeacon of Bar who was on his way to protest to the Porte in Constantinople about Kaçeniku, the sanjak bey of Shkodra, who had forced the archdeacon to pay 500 talers for a would be infringement by Dom Francis, his priest. Also in the retinue was Damian, the Emin of Bar and Ulcinj, who was on his way to Constantinople to better secure the position he had. This pleased me greatly in view of what might possibly happen to my nephew on such a long journey.

After the departure of the revenue collector, it seemed to me that it was the right moment to satisfy the wish of the Bishop of Sapa, so I set off for the villages of Troshan and Fishta. Chaplain Dom Primus Cinci was assigned to the church of the Madonna there, itself not badly furnished with garments and silver chalices. There I left orders for another large slab of stone to be made for the little altar and for it to be taken to the bishop to be consecrated. On Wednesday, a messenger arrived from the Rodon area near Durrës, sent by the has bey, a powerful leader in that region, with a letter inviting me to visit the area to provide consolation to his Christian subjects. The latter had appealed to him continuously to this end when they received word that I had arrived in Albania. He informed me that he wanted to grant them the favour and that the messenger, called John Çeka, would accompany me personally when he returned from Perast, where he was being sent on business. I responded that I would be very pleased to go once I finished my visit to Zadrima and that it would be quite sufficient if he ensured my security during the trip by sending some Turk with authority to accompany me.

Once the messenger had departed for Perast and I had fulfilled my functions in Troshan and Fishta, we set off for Sapa where we blessed the holy oils in the church of Saint George. It was here that the very reliable and intelligent Dom Primus Kryeziu was serving.

A Christian woman approached me here, the wife of a Turk. With tears in her eyes, she explained that she was the most unfortunate and desperate woman in the country because she was being kept in the power of a Turk (although she was his wife) and could not get away from him. She had been excluded from the sacraments and from attending church because the priest would not let her in, as he did the other Christian women. She implored me, suffering and enslaved as she was by that infidel, to order the priest and the bishop, whom she had approached several times, to admit her to mass and communion with the others. She was in such a state of despair that she was not to be consoled at all. I was afraid that things might get out of hand and that she might kill herself in order not to suffer from the misery any longer. I did not leave her before managing to calm her down somewhat with much reasoning, telling her that those who took the morally wrong decision to kill themselves in order to escape from the miseries of this world entered into another world of such dire misery that it would have been better for them not to have been born at all. I said that since she could not escape from the clutches of that man, as she claimed, and since, having had children with him, he would not accept to divorce her, she should pray to God to liberate her so that she could be admitted with the other women as she wished. I also promised to take the matter up with the bishop so that she could at least enter the church with the other Christian women and to see what else could be done. Such women were always excluded from confession because, having given birth to children, they had consented to sin, even though the force of such infidels is such that the poor women they take for their wives cannot fight them off if they do not consent. It does not seem right to me to exclude such women from church, of whom there are many throughout Albania and Turkey. Even if they are not allowed into confession, they should at least be able to retain their Christian faith and protect themselves from apostasy, to which they are driven by their infidel husbands. As the situation is, they abandon their faith more readily than if they had never entered a church at all.

Indeed I regard it as a great failing of this Christianity of ours to tolerate such detrimental abuse. They have never bothered to bring the problem up with their superiors, in particular with the Mufti, who is the spiritual head of the Muslims, so that he could expressly prohibit Turks from marrying Christians. In many places I did not fail to chastise the carelessness they had for the physical and spiritual health of their children, not to mention the honour of their families which was being put to shame, and told them that they would most certainly have to render account to God.

We left Sapa and proceeded to Hajmel and Renc where, as was mentioned earlier, Dom Joseph Bardhi was serving at the church of Saint Mary in Glina. We then descended from those villages which are all on the hilltops and arrived at the village of Mireri on a fair plain washed by the Drin, into which flows the river Gjadër. There, in the church of Our Lady, which is very small but which has a portico in front of it, we came upon chaplain Dom Nicholas Kabashi, and at the nearby village of Shelqet, its priest, Dom Joseph. From there, we proceeded to the village of Baba, where Dom John Trushi, also known as Scanderbeg, was serving at the church of Saint Pantaleon. This church, big enough to hold 300 people, was consecrated with crosses on the two facades and crosses on the other two (sides). It contains a silver cross, but the chalice and paten are made of tin.

Since the bishop was there with his vicar, I was requested to admonish the priest and demand that he abandon the concubine he had kept with him for many years. The bishop had admonished him several times and had set out to punish him, but this was in vain because he immediately went to the Turks who ordered the bishop to leave him alone. I admonished him to leave her, on pain of suspension from mass and of deprivation of his official status. He abandoned her immediately, but as soon as he heard that I had left for Rodon and Durrës, he returned to his abomination. Thus, when I returned to Zadrima, after the bishop and all the other priests had complained to me that he was incorrigible and had begged me to punish him, I issued a warrant against him, giving secret notice to the bishop to restitute him if he should mend his ways so that he would not end up on the streets, because he was an old man.

As we were in close proximity to the gardens and houses of Isuf Bey, who had retired to his own home when Cascapan, the Sanjak Bey of Shkodra, took office, I went to pay him a visit out of pure humanity and took him some presents as I was wont to do. He made many promises that he would take action and speak up about the issue of the men of Ulcinj. But these were nothing but empty promises. In the course of the conversation there, when he was talking to the abbot who had come with me, he revealed his dislike of the aforementioned revenue collector, although they had apparently patched up their relations. Taking advantage of the absence of the revenue collector, he had decided to go on the offensive and destroy Zadrima by looting the houses of the revenue collector. This he did several days later, telling the abbot that as soon as the Sanjak Bey of Dukagjin arrived, whom he had won over and who was to turn up shortly, he would punish the people of Zadrima because they had hindered him during the previous winter from making incursions, from which he had hoped to gain great booty and many animals and to put down the people of Dukagjin who were enemies of the sultan. By hindering him, they had proven themselves to be rebels because they were defending the enemies of their own prince. As I was their greatest spiritual leader after the pope, he wanted to allow me to decide what type of punishment they merited. Several days passed and I was once again in Zadrima at the village of Gryka where Dom George Bardhi, a pupil of the Clementine College and nephew of the bishop, was serving as vicar at the church of Saint Demetrius. This church was rebuilt from its foundations as it had been destroyed by an earthquake. There we received word that the aforementioned Sanjak Bey had arrived with a large retinue, had crossed the river Drin and had entered the plain of Mjeda. He had set up his pavilion not far from the ruins of the town of Deja, which had been destroyed at the time by Scanderbeg, and was waiting there to join forces with the Sanjak Bey of Shkodra and with Isuf Bey. He had gathered all the Muslims and Christians under his authority from Bar, Ulcinj, Trush, Kakarriq, Kukël and the banks of the Buna.

This news was of great concern to us all so I decided to leave the region and cross the Drin to get to the town of Kakarriq until the storm passed. But my nephew Angelo fell gravely ill from a certain stomach disorder. This reduced him to such a state that by the fourth day he could not hold any sustenance at all. Nonetheless, either because of his fear of the impending danger or because he did feel better, as he said, he managed to get back on his horse, Kakarriq being no more than three miles away. We all arrived happily because we were now in safety. Less than two hours had passed when he felt as if something had ruptured in his chest and his throat swelled. He begged me to commemorate his soul and invoked the intercession of the Blessed Virgin and of Saint Cecilia, his patron. He confessed to me but I could hardly hear the words which he endeavoured with such fervour to utter. I held him in my arms, giving him encouragement and praying to God in His mercy. When he lost his voice, I gave him absolution and left him in the care of the theologian father and the other priests. Stepping aside, I fell on my knees and prayed to our great Lord in His grace to save his soul. A little later, on May 13th, his soul departed the body in a sign of great attrition, leaving me in such pain and confusion that I hardly knew where we were. He was so young, a mere twenty three years old, of a lively nature and with an excellent memory. He had served me not only as a secretary but also for other needs. I had often asked him to preach to the people. He abandoned me at the hour of my greatest need during this distressful journey when we were sleeping without sheets, for the most part on the ground and in ubiquitous filth from which no one could escape.

Hearing of his death, the bishop and many priests came to console us for our loss which, being the will of God, had to be borne with patience and gratitude to the Lord.

In the meantime, the men of Zadrima, seeing that the enemy was about to attack, took counsel before the conflagration spread and before the Turks began to lay waste to their region. They resolved to appease the Sanjak bey and persuade him to turn back without causing them any further harm. They therefore collected food and other gifts and sent several of their elders to present them to him. Although he accepted the gifts, he made no promise and gave no sign that he would withdraw. Nor did he say openly what he intended to do since the men of Isuf Bey were as yet not ready for war. When the men of Zadrima saw this, they united under the command of Safer, the prefect of the revenue collector. The aforementioned Ferat Cotus Aga also took their side, and they took up position across from the camp of the Sanjak Bey, in support of whom Ali Cascapan, the Sanjak Bey of Shkodra, had arrived with his own forces, as had a good part of the forces of Isuf Bey. Interpreting this as a declaration of war, they went forth and attacked. During the first skirmish, some men were slain and many were wounded on both sides, especially on the Zadrima side. Realizing that the Turks were attacking with more men than they had themselves, as they only had the support of the men of Lezha, they began to retreat, nor could they hold their ground. Despite this, Safer, who was a young man of some twenty two years and who was very courageous, rushed to the fore and resisted the onslaught of the enemy. But in the end, seeing that even Ferat Aga was retreating with his company in disarray, he gave way to the enemy. The battle that day concluded with the victorious return of the Sanjak Bey to his camp, after having plundered Hajmel, Renc and the surrounding villages, including the home of the revenue collector. Everything was taken by the enemy as booty, and no house was spared. Barrels of wine were looted and many women were raped. The houses were put to the torch and so terrible was the conflagration which rose into the sky, that it could be seen from Kakarriq and the other villages nearby. As soon as the Turks began to approach, the men of Zadrima drove their animals up into the mountains so that they would not fall into the hands of their enemy. Only the men of Gjadër drove their animals to the village of Kakarriq. After the battles, not only did the Turks plunder those who were in the mountains, but they also threatened to come back and loot the other villages and set them on fire. The people of Zadrima were thus obliged to pay a huge sum of money which, after many endeavours, appeased the enemy and calmed the situation.

The people were thus allowed to return to their homes, but one morning, we received word in Kakarriq that over one hundred Turks from Ulcinj had crossed the river Drin there. They were on their way to steal the animals of the people of Gjadër and were now about to arrive. For this reason, all the people who had animals began to drive them quickly to Balldren or up into the mountains which rise about Kakarriq. I realized that there was nothing I could do to alter the situation because the barbarians had even been enraged by the requests made for the return of the goods which they had taken from me, and had threatened me. I immediately grabbed a shirt and stuck a little breviary into my pocket and, rushing out of the house with my retinue, came upon Dom Christopher who was making ready a barque. We jumped onto it and tried to punt across the canal in the direction of Balldren, but we could find no one whom we could pay to drag the barque out. Since the vessel appeared to me, in view of the emergency, to be moving too slowly, I decided to disembark as I was afraid that the Turks were too close at hand. We thus set off on foot, running as fast as we could to get away from the village and looking over our shoulders all the time to see if the Turks were behind us. We were about a quarter of a mile from Balldren, I believe, when I discovered that there were no barques there to take us across the canal, and that we had fallen into a trap. Indeed we would have fallen into the hands of the Turks, had they been after us, since, as we could find no ford to get across the canal on foot, there was no other choice but to swim. This horrified me, and all the more because I was covered in sweat and was afraid that I would catch my death in the cold wind which was blowing. But at that moment, a barque loaded with wood approached from Lezha and took us over to the other bank, though this took time because it could only transport us one by one.

When we arrived in Balldren, there was hardly anyone there. Since the watchmen there had spotted us running across the plain and had known there was a multitude of armed Turks in the vicinity, they thought we were Turks who were approaching to pillage and rape them. For this reason, almost all of the inhabitants fled into a nearby forest, taking with them their children and as many of their possessions as they could carry from their homes. When the watchmen recognized who we were and heard what had taken place in Kakarriq, they sent for the refugees and called them back. They also sent one man along the mountain road to see what the Turks were doing, and reinforced their watchmen at other spots. The scout returned and reported that the Turks had gone back to Ulcinj without causing any further harm. I therefore took a barque with my retinue and returned to the village that evening to wait for the messenger of the has bey in order to get to Rodon. I did not dare to set off on my own because I had to pass through territory bathed by the river Mat which was a small fiefdom run by an alay bey who let it be understood that wherever I happened to go, I would be caught and sent packing forthwith to Constantinople. It was therefore impossible for me to explore the country without being caught up in some unrest. But no one turned up. John Çeka, whom the has bey had sent, had, on my orders, brought a number of ships from Perast to load them with grain in Rodon. He had embarked on one of them and was travelling back by sea.

Not many days had passed, during which I was absorbed in thought, when the abbot arrived to inform me that Boe Gianchi of Mërqia had told him that he had recently been on business to the aforementioned alay bey. Not only had the alay bey altered the negative opinion he had held about me, but he had also expressed the wish to see and assist me, realizing that we were under the protection of the Porte in Constantinople. The alay bey was to visit his house in Mërqia in a few days' time where I would have an opportunity to talk to him. In view of this news, I thought it best to return to Blinisht. There, we received word from a messenger of the alay bey himself that the latter had arrived in Mërqia and that I was invited to meet him before he left to return to the Mat area. I therefore set off immediately, having made ready the usual tribute, mounted my horse and rode with the abbot to Mërqia, two miles away, not without apprehension about possible mischief on the part of the Turks. Having faith in God, in whose hands I had been during the whole journey, I carried on intrepidly. There, we came upon a large group of Turks in the shade near a spring, with many choice horses. The alay bey was sitting at a table set up in the grass. When he saw me, he welcomed me with a kind expression on his face and, seating me right away beside him, he spoke graciously and paid me many a fair compliment, inviting me, should I wish to travel to Rodon and Durrës, to meet him the next morning in Lezha to visit his home in Mat. It would be a good idea, he noted, for me to wait for the return of the revenue collector of the local Sanjak Bey in order to get the patents which would ensure my safe passage through those areas. They were not ready because the revenue collector had departed to accompany the Sanjak Bey for a couple of days, who was involved himself in the Persian war. As we were seated side by side, he asked me to sit across from him so that, as he stated, he could better enjoy my presence. He spoke and acted in such a distinguished manner that I marvelled just as much as I delighted in his behaviour.