| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1782

Karl Gottlieb von Windisch:

On the Kelmendi in Syrmia

The wild Kelmendi tribe of northern Albania allied itself with Austria during the Austro-Russian-Turkish War of 1735-1739. When Austrian troops withdrew from the southern Balkans, the Kelmendi fighters in Kosovo and in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar had no choice but to retreat northwards (here under their fictitious leader Clement). They eventually reached a safe haven in the region of Syrmia (Srem), situated between the Danube and Sava Rivers, west of Belgrade in present-day Serbia. There in 1749 or 1755, the Kelmendi settled in two or three villages where they preserved their language, customs and Catholic religion well into the nineteenth century. Indeed, there were still a few Albanian speakers to be found there as late as 1921. The following report, published in 1782 in the “Hungarian Journal or Contributions to Hungarian History, Geography, Natural Science and Recent Literature,” was the first scholarly article on the Kelmendi of Syrmia. Its author, Karl Gottlieb von Windisch (1725-1793), a German Hungarian merchant and scholar from Pressburg (Bratislava), includes an interesting sampling of the Albanian dialect of Syrmia. The original German transcription of the Albanian terms has been adapted to an English transcription here.

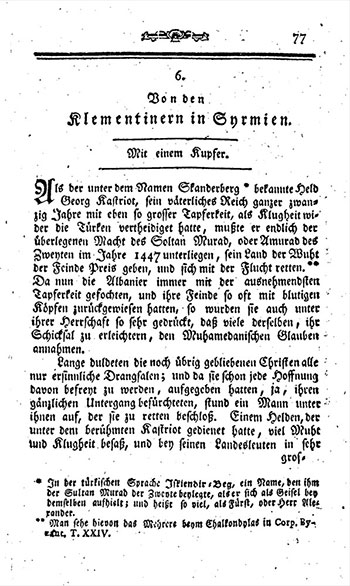

A Kelmendi man and woman

(Copperplate etching by Jacob Adam of Vienna)

Original German text.

Having defended his fatherland against the Turks with both courage and intelligence for twenty years, the well-known hero George Castriota, known by the name of Scanderbeg, was finally overcome in 1447 by the superior power of Sultan Murad, or Amurad, the Second, abandoned his country to the wrath of the Turks, and saved his own life by taking flight. Since the Albanians always fought the Turks with exceptional bravery and so often repulsed their foes who were forced to withdraw with bloodied heads, they were so severely oppressed under Turkish rule that many of them took on the Mohammedan faith to alleviate their suffering.

For a long time, the remaining Christians suffered all manner of affliction, and by the time they had given up all hope of being relieved thereof, and were indeed contemplating their end and destruction, a man rose among them who resolved to save them. Such an endeavour could not fail with a hero who had served under the great Castriota, who possessed much resolve and intelligence, and who was held in great respect by his people. Clement, such was the name of this patriot, revealed his plan to some of his fellow countrymen and the latter assembled a host of almost twenty thousand able-bodied and armed Albanians, whom in 1465 he led successfully with their families and possessions into the uninhabited and very remote mountains between Albania and Serbia. Here they constructed their homes, with protective barriers at all entrances and set up a small free state, electing their leader, the courageous Clement, as its head. From him arose the name Clementine [Kelmendi], which was adopted by their fellow countrymen who had remained at home and which they bear to this very day. The Turks, who were too weak to prevent this emigration, sent word to the Porte, and the latter dispatched a contingent of folk to attack them. But they defended themselves, not only on that occasion but in the later years always with great courage, and overcame all the assaults of their enemies. However, when, after the tragic Battle of Mohács in 1526, the Christians lost almost all the land in Illyria, they, too, were forced to pay an annual tribute of four thousand ducats to the Turks. They remained quiet in their mountains, grazed their animals and grew to become a reputable tribe. Finally, in 1737, together with many Bosnian, Bulgarian and Albanian families, they were convinced by the Greek Patriarch of Belgrade, Arsenius Jovanović, to emigrate to Serbia. Almost twenty thousand of these people gathered at the appointed settlement of Valjevo on the little Kolubra River, but they were attacked there by the Turks and cut to pieces with the exception of about one thousand men. Among those who managed to escape were three hundred men of Kelmendi with their wives and children, who turned to Belgrade and, thereafter, under the leadership of a priest called Suma, set up their homes in Syrmia [Srem] where, in the vicinity of Mitrovica, they founded the villages of Hrtkovci and Nikinci, the two being not far from the Sava River. These two villages are quite attractive and well-built, and have churches in which Franciscan monks hold mass. Since they are almost all devoted to the Roman Catholic faith, they hold mass in Latin.

The Kelmendi consist of six families (fis), three of which inhabit each of the said villages. As with other Oriental peoples, their customs are rather rough, but not savage. Their character traits include honesty, loyalty, discretion and an inclination to war. Among their failings are vengeance and violent fits of temper.

They marry at a young age – the men mostly in their twenties, but the maidens when they are thirteen or fourteen. Yet a Kelmendi will never marry anyone from outside his own nation. Neither are the womenfolk allowed to take outsiders as husbands. As such, they have remained unmixed to the present day. As to their build, they are large, slender people, taller than average, and their facial traits are regular and pleasant such that one can easily distinguish a Kelmendi from an Illyrian [Croatian]. The womenfolk are exceptionally beautiful and attractive when they are young and the men are accordingly very proud of them and are jealous to the extreme. It is therefore not advisable to speak to a Kelmendi woman even in the daytime without others being present because if her husband were to come by, it is likely that one would be killed on the spot.

Close relatives usually all live together in the same household, meaning that quite often that thirty or more families inhabit one house. Their houses are generally large and very clean. Their food is not tasty, but it is not as abominable as that of the non-uniate Illyrians. They make most of their food with cheese. They are also fond of drinking. Even their women rarely resist a glass. They like to sweeten their favourite drink, brandy (rakie), with honey.

Their primary occupations are agriculture and herding, in particular of sheep. They brought a very hearty species of this animal - with fine wool - with them from Albania. In Syrmia these animals are universally known as Kelmendi sheep. The women work indoors, spinning and weaving, and make all of their clothes themselves. They are also skilled at dying their wool with the juice of various herbs, as can be seen in their very colourful clothing.

Their clothes are rather curious, in particular those of the women. The men cover their heads with small red caps, identical to those that secular priests put on their tonsured heads, except that they have a small tassel on them. They keep their hair cut short and wear a piece of black crape around their necks. Over their shirts they wear a sleeveless garment that extends down to their knees and is usually red in colour. It is open at the top of the chest so that they can more easily cast it over their heads. Over this garment, they also wear a short jacket that extends to their hips and has a hem covered in many small buttons and balls of string, rather like the fur dolmans of the Hussars. Around their waists they wear a long sash that is wound around them several times, and around their ankles they bind colourful woollen material that is so attractive one could easily believe they were wearing stockings, and as footwear they wear a sort of drawstring shoes (opánki) that are well made and are laced with narrow straps. For weapons they use the so-called pusztován, which has a bronze or iron bullet that is inserted and secured in a barrel one and a half feet long. They carry it in their right hands and are highly skilled in its use. In their belts they carry a Turkish dagger and a pistol. From their left hips hangs a Hungarian sabre, and over their shoulders is a flintlock with which they can usually hit their targets at a distance of three hundred feet. The soldiers among them are only to be seen with these weapons and in the above-mentioned clothes at feasts, weddings, dances and other celebrations. At other times, they wear the same uniforms as normally worn by other imperial and royal border soldiers. However, both with these and with others weapons, the Kelmendi are exceptionally brave and dauntless solders who know no fear. They belong to the district of the Peterwardein [Petrovaradin] Regiment and make up an infantry company and half a Hussar company.

The costumes of the womenfolk of these people are extremely curious. The peacock, indeed the rainbow, could not be more colourful than a Kelmendi woman when she gets all dressed up. The headdress of the maidens (rubb) consists of a silk handkerchief with alternative yellow and red tuffs that hangs down their necks. They part their hair from the crown down to their necks and on each side they have three braids that fall over their shoulders. On top of their heads, they plait in their hair little bits of silver-coloured foil, flowers and other ornaments. The married women usually wear men’s hats that are different from ours only in that the part turned back is adorned with white ribbons. Their necklaces (posh) consist of strands of coral and glass beads. On the front, from their necks to their waists, they are covered in coins, for the arrangement of which they strive to achieve a certain symmetry. Their jackets (ling) of fine red cloth reach down to their hips and are fastened with only one button at the navel. These jackets have fringes all around and the sleeves only reach their elbows. From there down to their hands, their arms, like their legs, are covered in colourful woollen material. The fringes of these jackets are also adorned with tiny shells that we call cowries and that are used in Hungary to adorn riding equipment. Between their shoulders and elbows they have all manner of shells such that, when a couple of Kelmendi women stroll with one another, one hears jingling that resembles that of a sleigh ride. Perhaps they do this to draw the attention of the men. In addition to this, their whole jackets are adorned with yellow, red and green beads, and with white ones here and there among them in the form of little wheels (rueta). The sleeves, in particular, are decorated with these wheels and with silver braiding (chirip) and speckled silk tassels. They wear double belts: a wider one (posztát) of red cloth and a narrower leather one (brenz) on top of it, with a lot of iron buttons sewed into it and a thin iron chain hanging from it. Instead of a skirt, they wear an apron (pokoina) in front that consists of thick rows of yellow and red wool stitching that stretches down to their calves. On the other side, they wear a silken cloth (funtling) that hangs over their backsides. They cover their legs in wrappings as the men do and also wear opánkis as footwear. Their shirts (kemish) that extend to their calves are very tight-fitting and under them, they wear a coarse slip of woollen material.

Their dances are peculiar, too. To begin with, the men and women line up in two lines facing one another. Each of the women places her left arm over the right shoulder of the woman next to her, and then they begin to dance, with high-pitched, shrill voices and loud monotonous trills. Soon thereafter, two men come forth with unsheathed sabres in their hands and two pistols in their belts. They jump around in a droll manner for quite some time until one of the women advances to the middle, leaving her line. In each of her hands, she holds up a silk handkerchief. She does not move from the spot but stays where she is, turning to one of the male dancers and then to the other with the most curious gestures. They leap around her as if they were crazy, with no tact or rules. All this dancing goes on without pipes, bagpipes or any other instruments, as they do not know them. The sole accompaniment are their songs about the daring deeds of the heroes of old of their nation, in particular about the deeds of Prince George Castriota, known by the name of Scanderbeg.

Their language is called Albanian and is not related to any other Oriental or Western language. They use Latin letters on which they add many accents. In particular, their letter “z” cannot be pronounced in any European language. It sounds a bit like the Hungarian “z,” but foreigners have never succeeded in pronouncing it properly.

As examples, I would like to add a few Kelmendi words and expressions here, as well as the Lord’s Prayer, having written them down in our orthography and in the way we would pronounce them.

1. Numbers:

nya, one; due, two: tre, three; katter, four; penss, five; yasht six; shtát seven; tet eight; not nine; iviet ten; nishet twenty; trioviet thirty.2. Names of some nations:

Madjar, a Hungarian; Nyemts, a German; Turk, a Turk; Shlavák, a Slovak; Shkye, a Rascian; Harvat, a Croat; Bugarch, a Vlach; Madyub, a Gypsy; Harap, a Moor.3. Names of certain times:

dye, yesterday; sot, today; neser, tomorrow; paradye, the day before yesterday; dinni, winter, vera, summer; prodvera, spring; vieshta, autumn; dita, day; promea, evening; natta, night; evdiel, Sunday; ehonni, Monday; emart, Tuesday; emkur, Wednesday; eenti, Thursday; epratti, Friday; eshtule, Saturday.4. Names of some animals:

tyen, dog; mats, cat; kál, horse; ka, ox; lop, cow; uyk, wolf; harush, bear; laff, lion; orlin, eagle; korb, crow; pat, goose; dyet, rooster; peshch, fish.5. Names of parts of the human body:

kruet, head; sü, eye; vetula, eyebrow; pentesnait, eye socket; vesha, ear; metie, hearing; hunde, nose; miekra, chin; bulchi, cheeks; bal, forehead; fatye, face; perche, hair; buz, lips; dyuna, tongue; chieltsa, palate; tseap, teeth; tyafa, neck; kaptseri, throat; krahi or dora, arm; brüli, elbow; loni, ulna of the elbow; shpina dorz, back of the hand; shplak, palm of the hand; gishtya, finger; dyütüra, knuckle; fua, fingernail; parmzat, chest; brid, rib; plonsi, belly; zemra, heart; bushkni, liver; bushnki tebara, lungs; böza the behind; kar, the male organ; heret, testicles; pis, vagina; lesht, hair on the vagina; koma, foot; kofsha, thigh; dyuni, knee; gashtaydyunit, kneecap; gishta tekomz, toes in general; gishtimat, big toe; fempra, heel.6. Names of some relations:

niri, human being; trim, man; grue, woman; vaitsa, maiden; at, father; nonna, mother; bla, brother; ibiri, son; ebbia, daughter.7. Some Christian names:

Iváni, John; Prel or Tyetri, Peter; Páli, Paul; Dre, Andrew; Yakovi, Jacob; Lulashi, Luke; Mara, Maria; Liza, Elizabeth; Dil, Tekla; Onyd, Anna.8. Theology and schooling:

Lumizot, God; parizi, heaven; drety, the devil; peshkvia, hell; kisha, church; frat, priest; krüch, cross; mordya, death; vore, grave; letter, book; slob, letter of the alphabet.9. Some food and drinks:

buk, bread; mish, meat; tlüen, butter; gyáz, cheese; mola, apple; darda, pear; kumbula, plum; kirshia, cherry; ven, wine; piva, beer; uy, water.10. House and household equipment:

shtpia, house; soba, room; dera, door; asztali, table; stoli, chair; shtrati, bed; furumi, oven; brishk, pocketknife; fik, table knife; filushke, fork; lug, spoon; mashtek, bowl; shabbe, sabre.11. Names of colours and other adjectives:

zi, black; bar, white; kuty, red; mur, blue; ver, green; kaltu, yellow; sheshkim, brown; ilgua, sick; shtosh, healthy; zet, warm; ftoft, cold; mir, good; irun, bad; shum, a lot; pak, a little; shovt, bald.12. Names of some professions:

sholdat, soldier; doctori, physician; moleri, painter; zidari, mason; shushteri, cobbler; shnaideri, tailor; tishleri, joiner; zimmermanni, carpenter; kovach, smith; veknari, weaver.13. Various other words:

chielt, sky; dieli, sun; honna, moon; ulini, stars; deti, sea; ládya, ship; ushtri, war; pustohi, robber; ikmüe, fool; kurva, whore; mal, forest; tedashdun, love; irenim, anger; katundi, village; dyutedia, town; kral, king; kralitsa, queen.14. Some expressions:

Milne shtrasha, good morning; Mili proma, good evening; Tmile nat, good night; Se key fiet? How did you sleep?; Si ye aye shtosh? Are you in good health?; Sie kien a yekyen shtosh? Were you in good health?; Kadar zotün! Praise be to God!; Si ankyen zonya e zotnyiya, a yon kien shtosh? Shtosh kadar zotün! Was the lady or the gentleman in good health? Healthy, praise be to God!; Mil zere, welcome; Ura e par, Happy journey!; Kiof shtosh! Farewell; Zotün tavasht odene par! May God grant you a happy journey!; Un yes i pushtua, I remain a servant; Ti tyen! Oh, you dog!; Ti imalkua! You damn fellow!; Shpormu süsh tmat dretyi! May the devil take you!; Zamot yetyen ne Herdel? How long were you in Transylvania?; Pakmot, A short time; Si tíon tü? What is your name?; Apongdo moa? Do you love me?; Si song sae? What is this called?; Di mir Clementisht, I know (how to speak) Clementinish well; Ke dyun makaona, I love this language; Fort makaona ket nirì, I very much like that person.15. Some conjugation patterns:

Un edoa, I love; tin do, you love; ave do, he loves; na duam, we love; yu doni, you love; atta duen, they love. Another example: Un poha, I am eating; ti poha, you are eating; au poha, he is eating; na poham, we are eating; yu pohanni, you are eating; atta pohan, they are eating; unkomgran, I have eaten; ti kegran, you have eaten; au kagron, he has eaten; na kengron, we have eaten; yu kenigron, you have eaten; atta kangron, they have eaten. Un duame gran, I shall eat; ti domegran, you will eat; au domegran, he will eat; na doemegran, we shall eat; yu donimegran; you will eat; atta duonmegran, they will eat. Another example: Un popi, I am drinking; ti popi, you are drinking; au popi, he is drinking; na popim, we are drinking; yu popinni, you are drinking; atta popi, they are drinking; Un konpi, I have drunk, ti kepin, you have drunk; au kapi, he has drunk; na kempi, we have drunk; yu kennipi, you have drunk; atta kanpi, they have drunk; Un duamepi, I shall drink; ti domepi, you will drink; au domepi, he will drink; na doamepi, we shall drink; yu donimepi, you will drink; atta duonmepi, they will drink.16. The Lord’s Prayer

At ün chi ie mb chielt, Our Father, who art in heaven,

shentenün kiofte enneni tat, Hallowed be thy name,

art regenia yóte, Thy kingdom come,

ubafte volundeshia yote, Thy will be done,

sikuur mb chielt, mb zee, On earth as it is in heaven,

buken tank teper ditsimem eppna shode, Give us this day our daily bread,

e enneana ndiei faitoresi tan, As we forgive those who trespass against us,

e mos ne le meram mb ato kech, And lead us not into temptation,

pro na largó se shketye, But deliver us from evil,

Asto kiofte, Amen, or word for word: May it be thus!v. Windisch

[Karl Gottlieb von Windisch: “Von den Klementinern in Syrmien.” in: Ungrisches Magazin oder Beyträge zu ungrischen Geschichte, Geographie, Naturwissenschaft und der dahin einschlagenden Litteratur, Pressburg (Bratislava), 2 (1782), 1, pp. 77-89. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie. For the footnotes, the interested reader is urged to consult the original German text.]

TOP