| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1813

Thomas Smart Hughes:

Travels in AlbaniaBritish scholar, historian and travel writer, the Reverend Thomas Smart Hughes (1786-1847) was born at Nuneaton in Warwickshire and was educated at Shrewsbury School and at St John’s College, Cambridge. In December 1812, after graduating with a B.A. (1809) and a masters degree (1811), he accepted the post of travelling tutor for the wealthy young Robert Townley Parker (1793-1879) of Cuerdon Hall, Lancashire. For about two years, the two young men travelled through Spain, Italy, Sicily, Greece and Albania. The results of this extensive Mediterranean journey were published in his two-volume “Travels in Sicily, Greece and Albania,” London 1820. A second edition of this work, now covering 1,024 pages and illustrated with the drawings of Charles Robert Cockerell (1788-1863), was published in 1830 under the title “Travels in Greece and Albania.” Hughes began the Albanian part of his journey in Preveza which at the time marked the border between Albania and Greece, and continued on to Arta and Janina (Iôannina). The Albania he describes is thus primarily Epirus, the realm of Ali Pasha Tepelena, of whom he leaves us a good biography. From Janina, he then provides us with a detailed account of his excursion to the north of Albania (in modern terms, actually the south of Albania), i.e. to Libohova, Gjirokastra, Kardhiq, Tepelena, Berat, Këlcyra, Përmet, Konitsa and back to Janina, from which the following text (Chapters 9-11) has been taken.

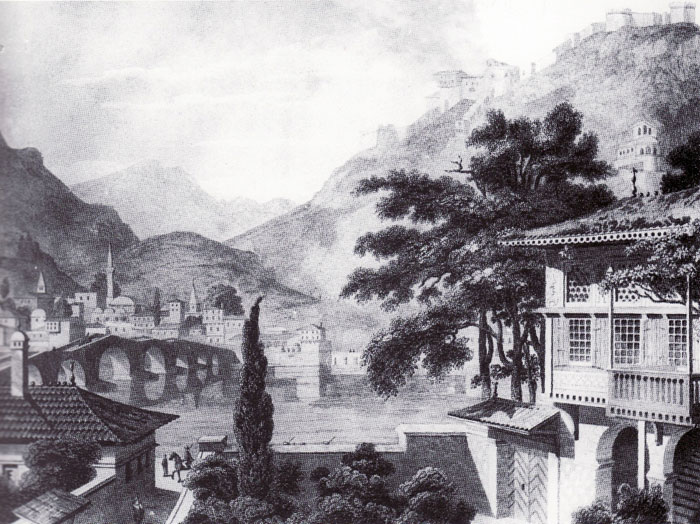

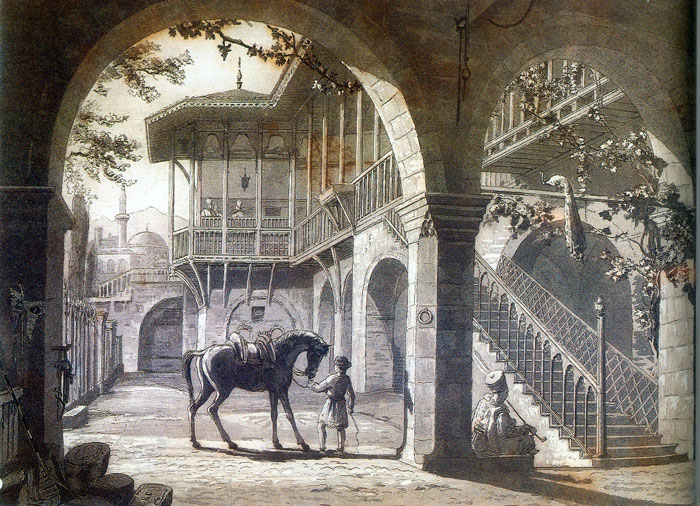

The house of Nicolo Argyris in Janina (Ioannina)

in Epirus (Drawing by Charles Cockerell, 1813).

Excursion to the North of Albania

CHAPTER IX

[…] – Excursion to the North of Albania – Zitza – Fall of the Kalamas or Thyamis – Tzarovina – Vizir’s Powder-Mills – Delvinaki – Misery of its Inhabitants – Inscription upon a Church – Violent Conduct of Mustafà – Valley of Deropuli – Reflections thereon – Palaia-Episcopi – Snuff Manufactory – Libochovo – Remains of Adrianopolis – Appearance of Argyro-Castro – Albanian Soldiers – Captain Gianko – Cries of Women for the Dead – Description of Argyro-Castro – Inspection of the Fortress – Visit to Salee Bey the Vizir’s youngest Son – The unfortunate Demetrio Anastasi – Statistical Paper sent by the Bishop of Argyro-Castro – Mistake of the Author respecting the Bearer.

On the 28th of March therefore at noon, one fortnight before the festival of Easter, we commenced our expedition, attended by Signore Nicolo, Antonietti, Demetrio, four suradgees, and Mustafa, armed with the plenipotential powers of his bouyourdee. In our first day’s journey we advanced no further than to Zitza [Zítsa], which is four hours northwest of Ioannina, situated upon some turfy knolls so as to command a fine view of that mountainous region through which the Thyamis flows into the Thesprotian plains; those plains wherein it once imparted verdure and luxuriance to the groves of platani that sheltered the Amaltheum. To their umbrageous shade the munificent Atticus retired a voluntary exile from the calamities of his country: there he endeavoured to forget his sorrows in the exercise of generous hospitality, in philosophical studies, and rural amusements, amidst scenery whose soft features were so congenial to the amenity of his own disposition. At the entrance of the village we passed a monastery on our left hand, situated in a tuft of fine trees upon a lovely eminence, and on the right a small serai belonging to the vizir, to which a granary is attached for containing the produce of his chiflick: throughout the whole of our route we constantly observed similar mementos of tyrannic power. Zitza contains about 150 houses, with four Greek churches: it is celebrated for a very excellent and fragrant species of white wine, made from grapes which have been exposed for about three days to the sun, and which has a peculiar flavour from the absynthus employed in its preparation. We procured from the convent a copious supply of this nectar, in which Signore Nicolo indulged his genius so freely as to bring on certain symptoms of an incipient fever, which, in the course of a few days, prevented our having the benefit of his company during the rest of this excursion. Next morning we resumed our journey through an undulating tract of country covered with vineyards: at one hour’s distance from Zitza we passed a beautiful cascade on the left hand, called the fall of Glizani, where the river Thyamis rolls over a rock about fifty feet in height and thirty in breadth, adorned on one side by a fine wooded knoll, and on the other by a picturesque watermill: the sun was shining brilliantly and a find iris playing over the spray. The scenery down the valley of the Thyamis would probably afford ample gratification to the lovers of the picturesque; our route lay upwards in a more northerly direction, which brought us in about four hours to the lake of Tzarovina, which is said to be unfathomable, and seems as if it filled up the vacuum of an exhausted crater; its great depth gives a deep azure to the transparent water, whose gloom is increased by some trees and shrubs which bathe their branches in its margin. Tzarovina is the place which Ali Pasha first occupied in his advances against Ioannina, and here he has built a small serai and fortress, which is mounted by a few cannon: below the lake, near the channel of the Thyamis, his largest power-mills are situated; but the article is wretchedly manufactured. Advancing about one hour further we turned suddenly to the right, up a very precipitous and magnificent glen, down which a small river flows into the Kalamas; at this point of the road we met a company of Albanian soldiers escorting several French and Italian prisoners who had been taken in league with some brigands in northern Albania. Antonietti entered into conversation with his countrymen, who did not much enjoy the prospect of an interview with the dreaded chieftain: as we did not hear of any punishment being inflicted upon these rogues, it is very probable that he received them into his service. After proceeding about a quarter of a mile up the valley, we crossed it and ascended a steep hill towards the town of Delvinaki. Here we met a number of women returning from the toils of agriculture with hoes, spades, and other implements of husbandry in their hands: one poor creature had two infants tied in a kind of bag over her shoulders. Almost all the cultivation of the ground in this district is left to women, whilst the men are absent during greatest part of the year in Constantinople, Adrianople, Saloniki, and other large cities, where they carry on the trades of butchers and bakers. Many of these sun-burnt daughters of labour had very fine features, the place being noted for the beauty of its women: some of them accosted us with great frankness and were very inquisitive as to the objects of our journey, and the place from whence we came.

At the top of the hill we burst suddenly upon the town of Delvinaki, seated in a large circular coilon, around which nothing but bleak and barren rocks appear. It contains four churches and about 350 houses, built for the most part in a style of neatness and comfort: but at least a hundred were at this time uninhabited, owing to the cruel exactions of Ali Pasha. He has long been desirous of converting the place into one of his detestable chiflicks, but has been constantly opposed in his endeavours by the inhabitants, who are equally desirous of retaining their independence: to subdue this spirit he has had recourse to the most oppressive avanias, and the most odious impositions, quartering several thousands of his Albanian troops for six months together upon the unfortunate district, and removing them only to introduce a fresh set and subject the inhabitants to greater misery. No resolution can withstand a force like this; and probably long before this time the miserable Delvinaki has sunk into insignificance. Its site has been by some mistaken for Nicaeum, and for Omphalium by others who have been misled by its umbilical appearance; but after a diligent investigation we could not discover a single trace of antiquity upon the spot. The only inscription we observed was one in modern Greek, carved upon the entrance of a new church and signifying that this sacred edifice had been erected in the year 1812, at the expense of the primates, in the reign of the high and mighty Ali Pasha.

At Delvinaki two principal roads branch off, one towards Delvino [Delvina] and Butrinto [Butrint], in the direction of Corfu; the other towards the great plain of Argyro-Castro [Gjirokastra] and the north of Albania. We took this latter, and enjoyed a superb prospect when we arrived at the highest point above Delvinaki, where the eye is carried down the vast chasm that we had passed the day before, and from thence over the extensive mountain scenery of the Kalamas. After passing through a wild rugged country for one hour and a half north-west, we arrived at the han of Xero-Valto [Xiróvalto], or the dried marsh, where the process of drainage has been carried on to a considerable extent, and a large quantity of very productive land brought into a state of cultivation. Near this place I had a serious altercation with our kaivasi Mustafa. He had just discovered that a Greek lad by whom he was attended on the journey, had lost a small parcel containing a shawl which had been committed to his custody. Irritated at this accident he drew his ataghan and beat the poor fellow most unmercifully about the head and shoulders with the back part of it: this passed over, but in a short time the Turk’s rage suddenly broke out afresh like a smothered flame; he began to repeat the castigation with double fury upon the unfortunate offender, and would probably have soon proceeded to use the edge of his scymitar, had I not thought proper to interfere; but it was only by a threat of complaining to the vizir that he could be persuaded to remit his indignation.

Soon after this affair we entered into the magnificent and spacious valley of Deròpuli [Dropull], on the western side of which stands the large city of Argyro-Castro. This plain, as enchanting as any which Arcadia itself can boast, is watered by the river Druno [Drino], commonly mistaken for the Celydnus of antiquity: it extends in length more than thirty miles, and varies from four to six in breadth. It is inhabited by a population probably of 80,000 souls; near a hundred towns and villages may be enumerated, which are seen partly studding the sides of its huge mountain barriers that rise above them in Alpine grandeur, partly hid within their sinuous recesses, or embosomed in thick foliage: flocks of sheep and large Epirotic herds range through the green pastures, and numerous goats browse upon the lofty precipices. A degree of animation is thus communicated to the solemn and impressive features of nature that is perfectly delightful: nor can I recall to mind a view which unites so much of the pleasing with the grand. In contemplating this scene imagination could not help picturing to itself the still more brilliant colours it may assume when the golden wings of Liberty shall be spread over its soil, when wisdom and justice shall direct the energies, restrain the vices, and encourage the emulation of its inhabitants: when industry shall lead into this terrestrial paradise the sister arts, teaching the transparent stream to fertilize every corner which is now deserted, mingle the various hues of every opening flower, spread the umbrageous grove along the plain, and cover the huge sides of every hill with foliage: when architecture shall distribute all around its elegant appendages of decoration, in the splendid dome, the lofty tower, and the columnated portico, scenes adapted to philosophical meditation or scientific research; and above all, when true religion shall once more raise her awful head amidst these shades, diffusing moral happiness among the people, recalling them from their long slumber of ignorance and barbarism, and animating their hearts to adore the Author of all good!

Entrance to the fortress of Libohova

(Photo: Robert Elsie, October 2012).

No district in Albania is half so populous as this, though the miserable tenure of the land, which is chiefly that of the chiflick, tends greatly to diminish its inhabitants. The principal articles of produce are corn, rice, and tobacco, besides vast flocks of sheep and goats, which are seen scattered over the mountains. We remained for about an hour at the beautiful village of Palaia-Episcopi, which is intersected by many transparent rills flowing from the upper parts of the mountain Mertzika, which turns the wheels of a number of water-mills, where the best snuff in all Albania in manufactured. A few miles beyond Episcopi we descended into the vale, and soon afterwards crossed the river nearly opposite the large scattered town of Libochobo [Libohova], lying upon a steep acclivity of Mertzika, and near a vast chasm in that mountain chain, through which a torrent pours its tribute into the Druno. This town, with its territory, is a chiflick belonging to Shaïnitza, the sanguinary sister of the Albanian tyrant, and at this time she occupied a large seraglio which had been constructed for her by the vizir. On the western side of the valley, nearly opposite Libochobo, and at no great distance from the river, Signore Nicolo pointed out the ruins of a small Roman theatre with a few vestiges of other ancient foundations, upon a spot which he designated by the name of Drinopolis, an evident corruption of Hadrianopolis, which in very early ages was called Phanote, and in later times of the Eastern Empire Justinianopolis. Argyro-Castro has succeeded to its consequences, though not to its site, upon which it is erroneously placed in the maps. In a little more than one hour we arrived under that city, whose unequal rocky acclivities, intersected by deep chasms and dividing it into several distinct partitions, give it a truly grand and imposing aspect. The houses, which are generally good, and belong chiefly to Turkish proprietors, are not contiguous, but stand in various positions some on commanding eminences, others beneath projecting crags, many on the ridges of precipices, but the greatest part upon the flat surfaces of rock, between its deep ravines: the whole appearance is singularly striking, and its fine effect is augmented not only by the minarets of its mosques, but by the grand fortress of Ali Pasha, which was at this time nearly completed, upon a much larger scale than has ever been adopted in this country for works of a similar description. At about five o’clock in the afternoon we entered this city and obtained excellent lodgings in a house belonging to a friend of Signore Nicolo.

After dinner we took a walk into the city, accompanied by a fine youth, the son of our host: our appearance attracted great notice and curiosity from the inhabitants. Many Albanians guards came up and entered into familiar converse with us, but there was nothing uncivil or impertinent in their address, and they very freely communicated all they knew respecting the works going forward, the views of the vizir, his wars with the Argyro-Castrites, and their subsequent capitulation. Amongst these troops it was difficult to distinguish the officers from the privates, by dress, by style of conversation, or by any assumption of superiority. A captain of artillery, named Gianko, was extremely civil, and accompanied us during the whole of our walk. This man stood high in the confidence of Ali Pasha, and was present with him at the massacre of the Gardikiotes, where he led on the first body of troops to fire into the court of the Han. In the minute circumstantial account which he gave us of that horrid catastrophe, he said not more than eighty persons were selected by the vizir as objects of clemency, whom he spared. During our excursion we heard many doleful cries and loud lamentations, proceeding from several houses: we inquired the reason of this circumstance from our guides, who informed us that the women were still wailing for their husbands and sons who had fallen in battle against the vizir: now many of these had been thus occupied at least seven years previous to the time we heard then; yet no one appeared surprised at the folly of this observance. So powerful is the force of custom! I remember listening frequently at Ioannina to the cries of a matron who had lost her husband seventeen years before in a Russian campaign, but had never omitted howling three times a day after she received the tidings of his death.

ὕφ' ἵερον ὧρσε γόοιοThe weather being extremely fine we never thought of abridging our excursion, by which means we considerably fatigued ourselves in making the circuit of his craggy city, standing, as it does, upon a steep acclivity and occupying a very extended space sufficiently large for double its population, which is not computed at more than about 15,000 souls. The bazaar is spacious, and appeared very well supplied with articles of commerce. The inhabitants, before the vizir’s conquest, were the greatest merchants in this part of Albania, and Argyro-Castro was a great depot for internal trade. Ali contrived to seize the persons of many of these traffickers, who were scattered about the country, and by this means facilitated greatly the reduction of the place. The most picturesque parts of its site are the chasms which intersect it, whose sides are lined with habitations beautifully intermingled with trees, shrubs, and gardens: these situations, however, are exposed to great danger from the mountain torrents, which, after heavy rains, or the melting of snow, sometimes sweep down with such a swell and impetuosity as to carry every thing before them. About three years ago a terrible inundation of this kind swept away more than sixty houses, with their inhabitants, in the deep ravine which lies to the north of the castle, where the ruins still attest the extent of the calamity. On our return home we found that poor Nicolo, being unwell, had retired to bed. An officer also had arrived from young Salee Bey to inquire after our health, and offer his congratulations upon our arrival.

Gjirokastra at dawn

(Photo: Robert Elsie, October 2012).Next morning, after having sent a messenger to the young bey, to apprize him of our visit and deliver a letter from his brother Mouchtar Pasha, we set out to view the fortress. We were received at the great entrance by our friend Gianko, and conducted into the apartment of the governor Hassan Bey, an elderly man, who had accompanied the vizir in most of his early campaigns: no greater mark of confidence could have been placed in him by his sovereign than the command of this fortress and the care of his favourite son and successor. The person of this old chief was fine, though his apparel was coarse, and even dirty; he wore a little red skull-cap on his head, and a large coarse cloak of goat’s hair thrown over his shoulders: he treated us with pipes and coffee, but spoke to us through the medium of an interpreter, as he was unacquainted with any other but the Albanian language. After remaining about half an hour in his little dirty apartment, which was totally devoid not only of grandeur but even of neatness and comfort, we departed, under escort of Gianko, to view the fortifications, deferring our visit to Salee Bey for the present, that we might not interrupt him in his studies. The area of this castle is extremely spacious, containing not only barracks for the accommodation of five thousand troops, but a very large seraglio and a mosque. The magazines are subterranean and well calculated to secure not only ammunition but provisions: the walls are of great thickness, though in some places they display too much haste in their construction: subterranean passages lead to all parts of the building, and water is brought by an aqueduct, from the hills that back it on the west, over a space of about six miles. In one apartment we were shewn a curious mill for grinding corn without either wind, water, steam or any other power but that of clock-work: it requires to be wound up only once in twenty-four hours, during which time the stone makes 42,000 turns and grinds 1400 ochas of flour: it is the invention of a poor Greek artificer, who had worked with some Frenchmen at Taigan in the Crimea. From the battlements of this castle we had a noble view of the grand plain of Deròpuli, presenting an appearance of fertility and animation that is wonderful in this country. Forty cannon only were as yet mounted, but forty-five more were expected: that end of the fortress which is turned towards the mountain was defended solely by one large traversing gun at the south-west bastion: amongst others we remarked several pieces of English and French ordnance, together with about a dozen brass field-pieces standing on their carriages upon a platform near the south-east corner. I observed to Captain Gianko that the whole castle was commanded by a position of the south-west, and he said it was in contemplation to secure that by the erection of a strong outwork. If artillery could be brought to play upon it from the heights above, on the western side, it could not sustain a siege of two hours: but whilst Turks only are the enemies to attack it, its deep ravines are a sufficient defence against this danger. About 1500 peasants were busily employed in various labours about this building, and by a shamefully oppressive avania were allowed only rations of coarse calamboci bread, by way of remuneration: and this for the forgery of their own fetters!

After having minutely inspected the works, we adjourned to a small house adjoining the serai, for the purpose of paying our respects to Salee Bey, whom we found seated on the divan in company with his tutor. He received the respectful obeisance of our attendants with a dignity that would have surprised us, if we had not known that lessons in etiquette are among the first in which youth of high rank in these countries are instructed: he appeared pleased to see us, and asked many questions respecting his father and brother; but we thought him deficient both in manner and acquirements when compared with his nephew little Mahmet Pasha, who is about his own age. Motioning Nicolo to sit hear him on the sofa, he questioned him, in a low tone of voice, respecting a difference which he observed in Mr Parker’s dress and my own, as why he wore a sabre and I did not, why his pantaloons were blue and mine white; but he desired his informant not to look at us, lest we might think he was discoursing about us, which, he added, would not be courteous towards strangers. The complexion of this youth was fair, his hair and eyes light, and his physiognomy bore a very strong resemblance to that of his father; he was considered docile, and rather of a mild disposition, although I understand he has since shewn some traits of that vindictive spirit which distinguishes the paternal character. No pains appeared to be spared in his education; he was not only instructed in the Turkish, Albanian and Romaic languages, but was daily trained in bodily exercises, whilst every opportunity was taken to ingratiate him with the Albanian tribes that were to be his future subjects. At our departure he promised to send us letters to various governors of cities that might lie in our route, as well as one to his mother, resident at Tepeleni [Tepelena], who, he added, would be proud to entertain Englishmen as her guests. We then took our leave, when the young bey arose and accompanied us to the door of his apartment, wishing us a pleasant journey and every kind of prosperity.

In the evening an Albanian colonel, accompanied by a dozen guards, brought the promised letters to our lodging: our friend Gianko also called, and two or three Greek gentlemen dropping in, we detained them all to pipes and coffee and discussed the valour and politics of Ali Pasha over a flowing bowl of punch made in Antonietti’s best manner.

The next morning we intended to have resumed our journey, but Signore Nicolo complained so much of the state of his health, that we thought it right to remain another day in Argyro-Castro, to see what turn his complaint might take. Early in the morning, being accompanied by Demetrio, I ascended the mountainous steep behind the city with an intention of gaining the summit; but found this quite impracticable, on account of so many deep chasms which presented themselves in our path. We returned therefore, after having enjoyed a view of the plain which fully recompensed us for our trouble. About noon, Nicolo feeling better, I walked out with him, and we paid a visit to poor Demetrio Athanasi, whose fine house at Ioannina the reader may recollect was seized by Ali for the sake of his nephew the Pasha of Ochrida. A small miserable tenement was now the residence of this wretched family who had been long accustomed to all the comforts and the luxuries of life. Its master appeared gradually sinking under the attacks of a slow fever, nor did any consolation or any medicine afford him relief. The cause of this worthy man’s exile and the confiscation of his property, when explained, is enough to make one shudder at the insufferable tyranny under which he was doomed to breathe; it was a refusal to let one of his beautiful children become a victim to the despot’s lust within the walls of his accursed harem!

View from the fortress of Gjirokastra

(Photo: Robert Elsie, October 2012).Soon after our return, a person was introduced who had bought, at my request, a paper from the Bishop of Argyro-Castro, containing the number of villages and inhabitants in the valley of the Druno. As I understood the bearer had taken the trouble to copy out this document for my use, I presented him with a small pecuniary remuneration; this he accepted with great good-nature, for I found afterwards, to my utter confusion, that I had been feeing one of the most dignified canons of the church. I had not made such a mistake since the time when I gave a pair of English razors to the old dragoman of Tripolitza, who prided himself upon the longest beard in the Morea, which steel had never touched since it first sprouted from his chin and which he nourished with more than parental attachment. Besides the statistical paper, my friend the canon gave me a curious history of the settlement of Argyro-Castro, or rather of Drinopolis, written in excellent Romaic, which refers its foundation to Theseus King of Athens, and contains numberless inconsistencies and absurdities.

CHAPTER XDeparture from Argyro-Castro – Fortress of Schindriada – Fountain of Viroua – Visit to the Ruins of Gardiki – Han of Valiarè – Road to Tepeleni – Arrival there and Reception at the Grand Serai – Hospitality of the Sultana – Ibrahim the Albanian Governor – Description of Tepeleni – Serai burnt down – Curious Anecdote of Ali Pasha connected therewith – Excursion to Jarresi – Gardens of the Serai – Departure from Tepeleni – Mad Dervish – Route to Berat – Magnificent Scenery, curious Dwelling-Houses and Manners of the People – Approach to Berat up the Valley of the Apsus – Lodging in the Suburb of Goritza – Curious Fashions of the Women – Visit to Hussein Bey – Old Usuff Araps – Turkish Chargers – Ascent up the Acropolis – Buffaloes – Ancient Isodomon in the Fortress – Historical Accounts – Great Plain – Ali’s Character in Berat – Extract from Mr Jones’s MS, Journal relating to Apollonia, Delvino, Phoeniké, &c.

April 2d – Signore Nicolo being still indisposed, it was settled that he should remain a few days at Argyro-Castro and then join us on our return to Konitza, where he had a sister married and settled. Accordingly we set out this morning, without him, in a northerly direction along the western side of the valley. We left at some distance on our right the fortress of Schindriada crowning the summit of an eminence which rises abruptly out of the plain. This was built by the vizir about nine years before the surrender of Argyro-Castro, for the purpose not only of annoying his enemies but protecting that line of country through which he was obliged frequently to pass. In one hour and a half we came to a deep fountain, close to the road, called Viroua, where the water rises, as it were, out of a profound crater, curling at the surface in broad eddies: it then flows precipitously over a steep rock and forms at once a river: this I have endeavoured to represent in the vignette prefixed to this chapter. In about half an hour more we turned suddenly to the left, through an opening in the mountain barrier; the road was no more than a fiumara, over which at this time a torrent from the melted snow was flowing rapidly towards the plain, and made it sometimes very difficult for our horses to keep their legs. The ruins of many villages both on the right and left scathed by the destructive flames of war, testified the cruel mode of warfare practised by the Albanian soldiery. We toiled for more than an hour up this wild and rugged glen, when the mountains, suddenly taking on each side a bold sweep, formed a perfect amphitheatre and displayed to view the ruins of Gardiki [Kardhiq] spread over the sides and summit of a conical hill which rises in the very centre of its vast area: high above this fine circumference of hills appeared the huge summits of Acroceraunia whose wintry snows, now melting, allowed the spiry fir here and there to peep out from beneath its resplendent mantle: few cities could boast of so superb a situation. At a little distance from the foot of the hill we passed a large farm house which once served as an outpost of the garrison: the doors and walls, pierced with ten thousand bullets, testified the sharp conflicts it had lately sustained. In the plain beyond we observed a small village peopled by Suliots, who have been congregated together in this spot by the pasha’s orders; it is thought he meditates to take some signal vengeance upon these unfortunate victims when he has got as many as possible within his grasp.

The ruins of Kardhiq

(Photo: Robert Elsie, October 2012).

Having crossed a deep ravine, which defended the city of Gardiki towards the south and east, we ascended up its steep hill by the winding narrow path which but a short time before led Ali’s troops to victory. Upon a detached eminence on the right hand stood a small citadel, whose ruined walls present nothing worthy of notice: after inspecting them we entered at once into the mournful skeleton of Gardiki, “a peopled city made a desert place,” where no living beings disturb the solitude, except serpents, owls, and bats. A chilling kind of sensation, like the fascination of some deadly spell, benumbs the senses, and almost stops the respiration of the traveller, who treads as it were, upon the prostrate corpse of a great city, just abandoned by the animating spirit. The feeling is far different from that which he experiences amidst the fine ruins of antiquity, whose aspect, mellowed down by time and unconnected with any terrible convulsions, inspires only pleasing melancholy, or animating reflections: but here the frightful contract of a recent and terrible overflow appals him; his heart sickens at the sight; and whilst the deep silence in broken only by the breeze which sighs around the ruins or amidst the funereal cypresses which here and there wave over them, he almost expects to meet a spectre at every step he takes.

Amidst these monuments of destruction we found our progress often barred by vast heaps of ruins: nor after an hour’s ramble did we discover one habitation which had not suffered in the work of demolition; even the tombs were razed to their foundations, and the very mosques themselves had not escaped profanation; so duly had the vengeance of an implacable enemy been executed: one minaret alone peered out amidst surrounding masses, to the top of which we ascended, that we might contemplate the whole extent of this melancholy scene. From hence we observed a solitary dervish stealing gently from the covert of some ruins at a distance. Probably the poor man had come, in spite of Ali’s dire anathema, to live and die amidst the relics of this once populous city, to weep over the memory of former days, of friends departed, and connexions broken. Yet the heart of him who has thus rudely torn asunder all the bands of social life, glories in the dreadful deed of vengeance, the memory of which, instead of festering like a canker in his bosom, seems rather a source of joy and exultation.

In our return down the fiumara we marked with surprise the immense quantity of sand and pebbles which a wintry torrent in these mountainous countries will carry down into the plain, overwhelming many acres of fine land at its mouth with the most unfruitful materials.

―――― d’infeconda arena

Semina i prati e le campagne amene.Opposite, in the plain, we observed the deserted han of Valiarè, whose walls enclose the mouldering bones of the murdered Gardikiotes. The door is nailed up, over which an inscription openly testifies the bloody deed, and gives warning that a similar punishment awaits the wretch who shall dare to offer any dishonour to the family of Ali.

At about eleven miles from Argyro-Castro, and nine from Tepeleni, the great plain contracts itself into narrow valley, where a good han appears, near a lofty bridge of a single arch, thrown across the Druno. Soon afterwards this valley becomes a narrow defile, compressing the bed of the river into a very narrow compass between its parallel ridges of mountains. At the distance of a mile from Tepeleni we passed that magnificent defile called anciently the Fauces Antigoneae, where Philip was attacked by the Consul Flaminius, and where the rapid Voïussa [Vjosa], the Aeas or Aöus of antiquity, receives the tributary stream of the Druno between the opposite heights of Asnaus and Aeropus: it flows from seven fountains on Mount Pindus, beneath the town of Mezzovo, and passing near the cities of Konitza, Ostanizza, Premeti [Përmet], Klissura [Këlcyra], and Tepeleni, falls into the Adriatic below the ruins of Apollonia.

The shades of evening almost hid Tepeleni from the view as we entered the town, where we were received into the grand seraglio, and accommodated with the best apartments: as soon as we were settled, the Albanian governor entered to offer his congratulations upon our arrival, bringing also those of the Sultana, with an intimation that her ladies were preparing to send us a dinner from the harem. We returned a proper acknowledgment of this unexpected favour, together with a letter which we had brought from Salee Bey to his mother: and to say the truth, nothing could exceed the civilities paid us during our stay by this unseen benefactress: we learned however that female curiosity prompted her to take a transient view of her guests, through a latticed window, as they passed into the great court of the seraglio. Our unexpected arrival obliged us to wait a considerable time for dinner, which was announced by musical instruments and brought in by a crowd of slaves and Albanian guards, who nearly filled the room, and stood around the table during the time of our repast; Ibrahim, the Albanian governor of the serai and town, dined with us, and paid due respect to the dainties of the harem: he was an intelligent man, full of conversation, and well acquainted with the early life of Ali, concerning whom he amused us with many interesting anecdotes; for he remembered the vizir when he had not where to lay his head. He spoke to us also of his mother, whom he described as possessing all the martial qualities of an Amazon, with the spirit of a Laconian matron: he extolled the good qualities of Salee Bey, and appeared as if he entered into his master’s projects respecting the future destiny of that youth. Thus the evening passed very agreeably till bed-time, when a party of slaves came into the room, bearing in their hands, and on their heads, wilken mattresses, rich coverlets of embroidered velvet, pillows of the same material, with a species of fine Constantinople gauze for sheets, and all the apparatus of bed-furniture, fit for princes in magnificence. These articles were spread out upon the sofas of the divan, and we retired to the comfort of sleep, which requires not much wooing from those who have undergone the fatigues of travelling in this country: not even the novelty of the scene or the roughness of the sheets could long keep us awake. As soon however as we were laid out in state, the governor, with several other officers of the palace, came into the room under pretence of wishing us good night; but in reality to satisfy their curiosity regarding the mode in which Englishmen lie in bed. I observed them sneering a little at our effeminacy: their own custom being to throw off merely the upper garment and recline upon the cushions of the divan, with no covering but a thick paploma, and that only during the cold season. From this cause, and their great aversion to a change of linen, the hircinus odor attaches itself very strongly to Albanian society.

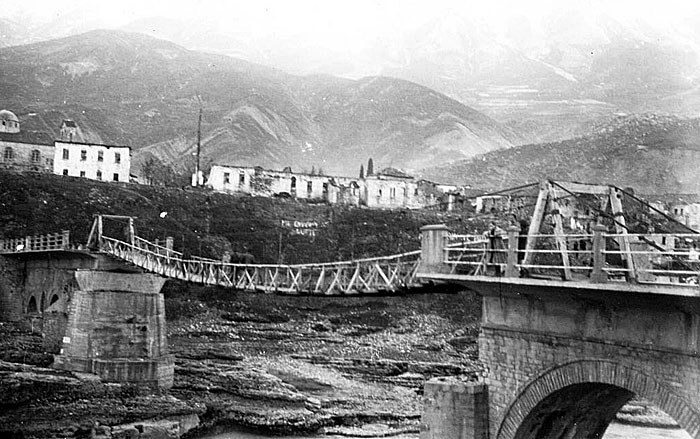

The palace of Ali Pasha in Tepelena,

Engraving of Edward Finden,

based on a drawing by William Purser

(early 19th century, private collection,

United Kingdom).

Next morning we took a view of the town, which is only interesting as the birth-place of the present rule of Epirus. It stands upon the high bank of the Voïussa, which is here about as broad as the Thames at Kew, and like the Araxes indignant at a bridge: a very fine structure of this kind, which was thrown across it during the times of the Lower Empire, had been left in a ruinous state by the violence of the stream, and though the vizir expended 1500 purses in repairs, all his efforts were in vain; not quite two years before our visit, a dreadful inundation swept away the new works and left the old broken arches in their former state of a picturesque ruin. A very handsome reward is still proposed by Ali to any engineer who shall enable him to defy the current. Tepeleni contains about 200 houses, with a population exclusively Albanian; it possesses no architectural beauties, if we except the grand seraglio which Ali has build upon the site of his paternal mansion. This is a very spacious edifice standing upon a fine rock at the edge of the cliff: I speak indeed of the seraglio which then was, for a new edifice has lately been erected upon the ruins of the former, which was accidentally burnt by fire in 1818. The account of this conflagration, which I received from an Albanian correspondent, is worthy of detail, since it tends strongly to illustrate the character of Ali, which these pages are intended principally to portray.

The mischief was occasioned either by the negligence of some attendants in the train of Salee Bay, who was at Tepeleni on a visit to his mother, or by a storm of thunder and lightning which occurred at the time. However this may be, about the middle of the night the whole palace was in flames. In the horror of the scene the Sultana, with all the other ladies of the harem, endeavoured to make their escape through the doors of the apartments, but were actually met and driven back again by the ataghans of the eunuchs appointed as their guards: these wretches would rather have seen them all fall a prey to the devouring element, than exposed to the lawless gaze of public curiosity: such is the force of Mahometan prejudice! In this extremity they let themselves down through the casements of the windows which they broke and tore away for that purpose. Before morning scarce a vestige was left of that superb edifice which Ali had raised upon the residence of his forefathers. His rage and fury were so dreaded, that it was thought proper at once to ascribe the cause of this misfortune to the effect of lightning, without hinting at the possibility of any other. As soon as he received intelligence of the misfortune he set off instantly, and scarcely rested day or night till he arrived at Tepeleni; there he felt some consolation when he found that the subterranean chambers in which he kept his plate and other valuables were uninjured, as well as the great tower in the garden which is the depository of his treasures. He now set his head at work to contrive some plan for restoring the edifice without incurring any expense. His first care was to issue proclamations throughout his dominions stating that the vengeance of heaven had fallen upon him, and that Ali had no longer a home in the place of his ancestors. He called therefore upon his loving subjects to assist him in his distress, and fixed a day on which he expected their attendance. On the day appointed Tepeleni was crowded with deputies from the various districts of Albania, with his old associates and intimate friends, his children, and relations of every degree. At the outer gate of the seraglio Ali was seen seated upon a dirty mat, cross-legged and bare-headed, with a red Albanian cap in his hands to receive contributions. He had been cunning enough to send large sums of money beforehand to several of his retainers, from whose poverty little could be expected; and these they now brought and restored to him as if they had been voluntary presents from their own stores. When therefore any bey or primate offered a sum inferior to his expectations, he compared his niggard avarice with the liberality of others, who he felt certain had deprived themselves even of the necessities of life for his sake, refusing the present in the following terms: “What good will this offering do for Ali, a man afflicted by the Divine vengeance? Take it back murrie, take it back, and keep it for your own necessities.” This hint was quite sufficient to double or even treble the contributions, and by such means he collected a sum of money which enabled him not only to rebuild his seraglio, but to add very considerably to the treasures in his garden.

After breakfast this morning we set out to investigate the ruins of a palaio-castro, which, as we heard, lay at about one hour’s distance from Tepeleni. The road led us for about a mile up the stream of the Bentza [Bënça], a small river which flows into the Voïussa below the town. At a village of the same name, its bed is contracted by two converging ridges of Mount Argenick, a branch of the great Acroceraunian mountains. Here the vizir has established extensive powder-mills, and the scenery is very romantic. We crossed the river by a handsome bridge of a single arch, and proceeded in an easterly direction to the object of our excursion. This we soon discovered upon a moderate eminence, in a small district called Jarresi [Zharra], but we were disappointed in our expectations of finding either a Greek or Roman fortress; it appeared from its mode of construction scarcely so ancient as the time of Justinian, and may possibly have been erected by the Norman invaders of this country in the reign of Alexius Comnenus.

On our return to Tepeleni we took a walk in the gardens of the seraglio, which are extensive, and laid out by two Italian gardeners, somewhat in the style of their own country. These men were deserters from the French army in Corfu, whom Ali received gladly into his service, giving them houses, with a good salary, and wives from his own harem of Tepeleni.

Ὀικόν τε κληρόν τε πολυμνήτην τε γυναῖκαWe caught a view of these liberated captives during our walk, but they seemed to possess neither beauty nor elegance. The great tower, or treasury, in which more than two millions of money are withdrawn from circulation, is a vast oblong building three stories in height, and secured by ponderous doors, of which Ali alone keeps the key. Such are the resources of ambitious tyrants who are unable to establish or sustain public credit by any constitutional guarantees, and are dependent upon their people’s fears rather than their love for support.

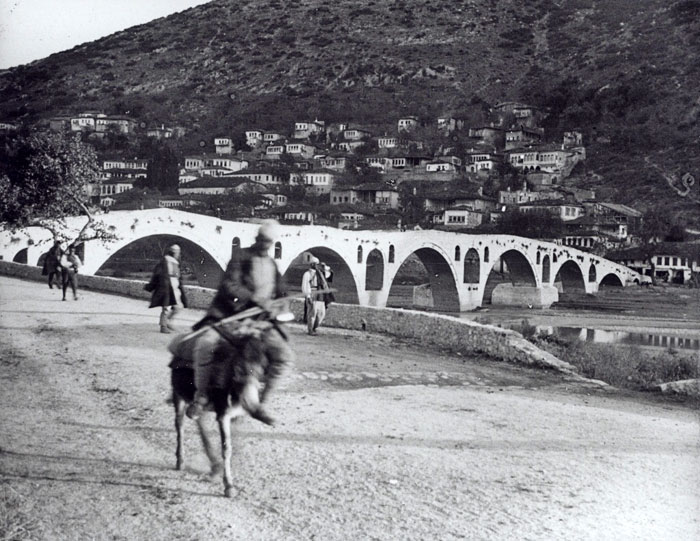

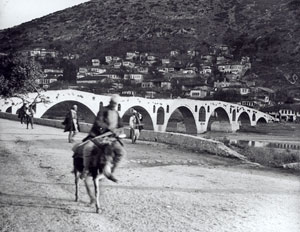

View of Berat (Drawing by Charles Cockerell, 1813).

This day the sultana sent us a very excellent dinner from the harem, consisting of soup, ragouts, pilau, and various kinds of pastry, at which we were again gratified by the company of the governor. When the wine, of which he partook freely, had opened the heart of this worthy old Mussulman, his tongue became very fluent, and he entertained us with many curious and highly interesting anecdotes. This night we slept in splendid misery, and if I had not feared it might have been taken for incivility, I should have made a retreat into my snug little trunk-bed.

Early in the morning, after sending our best acknowledgments to our kind hostess for the hospitality we had experienced, we departed for Berat, taking Demetrio alone to attend us, and sending Antonietti with greatest part of the luggage through the defile of Antigonea to wait our arrival at Premeti. Upon mature consideration we preferred this tour to one which we at first contemplated along the coast of the Adriatic through Avlona [Vlora] and Delvino. That part of Epirus however has been subsequently visited by my friend the Rev. William Jones, who has kindly permitted me to make an extract from his manuscript journal, which will be found at the end of this chapter. As we descended towards the river, a mad dervish came jumping out of the portico of a new mosque near the serai, vociferating the most horrid imprecations against our Christian heads: the application of some paras quickly changed his tone, and the poor wretch remained dancing in the wild manner of his fraternity upon the bank, and eulogizing us in a most Stentorian voice till we were out of sight.

We crossed the Voïussa in a curious kind of trough, scarcely oblong in shape, but broader at one end than the other: the horses were driven with great shouts and cracking of whips into the river and made to gain the opposite bank by swimming: much confusion ensued, as some of the animals swam to a considerable distance down the stream, and others turned back when half way over: at length all arrived safe at the other side when, the saddles and luggage being replaced, we proceeded on our journey, and followed the course of the Voïussa north, to the distance of six miles, where it takes a sweeping turn westward, in the direction of Apollonia. The country now began to lie in a regular ascent, the road winding along the side of continued chains of low hills, rising one above the other. Nearly half way between Tepeleni and Berat we gained the highest point, when the views both before and behind us were extremely grand. In front we looked over a mountainous country, which can be compared to nothing so well as to the Atlantic in a storm: the extreme horizon verging to the left was bounded by the hills around Durazno [Durrës], that on the right by the mighty Tomour, which in bulk and general outline bears a greater resemblance to Aetna than any mountain I have seen. His huge head, clothed in a bright snowy mantle, rose splendidly sublime, like a citadel which the mountain genius of this wild territory might fix upon for his dwelling. Behind us was a spectacle still more superb: the Voïussa pouring down its foaming torrent between its Alpine boundaries; the distant summits of Pindus; the noble scenery of Derópuli; and the vast mountains of Kimarra [Himara], those dreaded heights of Acroceraunia, little inferior to the huge Tomour itself, which reflected in their snow-capt peaks the brilliant tints of the rising sun. After having feasted our eyes some time with these enchanting prospects, we descended into a deep fiumara, through which the road continues for about two hours: from this point all the rivers take a different direction, and instead of flowing towards the bed of the Voïussa, seek to pour their tribute into the river of Berat, the ancient Apsus. The manners of the people in these northern regions seemed much more wild and barbarous than those to which we had hitherto been accustomed. The peasants stared at us with a curiosity bordering upon insolence, whilst the women and children ran away, or if we came upon them unawares, turned their faces from us till we had passed. The villages, some on the declivities of the mountains, and others in the valleys, had a very dull and gloomy appearance, the houses being built of a dark red stone, all widely distant from each other: their construction served to give us a proper notion of that dreadful insecurity which must have rendered society a perfect state of misery before the conquests of Ali Pasha: each mansion was formed like a tower, the entrance to which was in the second story, at least three yards from the foundation, and whenever any member of the family wanted ingress or egress, a rope ladder was lowered and drawn up again by the rest: no aperture admitted the free light of heaven to these keeps, or dungeons, except a few loop-holes pierced in the wall, from whence the family muskets might be pointed against an advancing foe. Almost all the inhabitants of these regions profess the Mahometan faith, though they know as much about Mahomet as the Grand Lama: they abjured Christianity to save their possessions, and are despised equally by the Osmanlis and Greeks. A few years ago this country was quite impassable to a foreigner; every house which he had ventured to approach would have teemed with muskets aimed against his life. Surely even the tyranny of Ali Pasha is happiness compared with such a state as this!

When we arrived within a few miles of Berat, which is distant twelve hours from Tepeleni, the aspect of the country appeared more pleasing and cultivated, and the manners of the people more civilized. Just about sun-set we entered a charming valley extending towards the north, through which a gentle stream flows into the Apsus and distributes verdure and fertility in its course. Here we observed, in several instances, a nearer approach to the country villa than we had before seen in Turkey: some houses on the banks of the river were surrounded by a lawn, plantations, and fences, which, with a little more taste, might have been rendered most agreeable retreats. The rich mellow tints of the sky shed an additional lustre upon the landscape, as we turned to the right up the magnificent valley of the Apsus, where the towers and minarets of Berat burst full upon the view, with huge Tomour rearing his gigantic head into mid-air; the grandeur of the view was so striking, that we should have thought this a sufficient recompense for every fatigue in our journey from Ioannina.

Such scenes as these will justify the bard, who thus describes them after his inspection of the most classic regions that have been celebrated in the songs of poets.

From the dark barriers of that rugged clime,

Ev’n to the centre of Illyria’s vales,

Childe Harold pass’d o’er many a mount sublime,

Through lands scarce notic’d in historic tales;

Yet in fam’d Attica such lovely dales

Are rarely seen; nor can fair Tempe boast

A charm they know not; love’d Parnassus fails

Though classic ground and consecrated most

To match some spots that lurk within this lowering coast.At the distance of about half a mile up the valley a fine bridge of eight arches thrown across the Apsus, leads into a picturesque burial-ground and suburb of Berat, to the east of which rises a noble hill crowned by the fortifications of the citadel and serai of the pasha; both of these have been lately much enlarged by their conqueror. From the bridge a road runs along the right bank of the river to the city, which is higher up the valley, and lies chiefly around the south-east side of its acropolis. The inhabitants of Berat being almost entirely Mahometan, we were lodged with a Greek merchant named Nicolachi, in the large suburb of Goritza [Gorica], on the left bank of the Apsus, where the Christian part of the population have their dwellings. Though this house was one of the best in the place, and the family turned out of the best room in it for our accommodation, its filth and suffocating smell was quite appalling! We found the master seated round the fire with half a dozen loungers who were nearly hid from our view by a dense smoke which issued into the room instead of passing through the chimney. How insignificant such trifles appear to those who are accustomed to them, may be inferred from the following short dialogue which took place between Mr. Parker and our host: “C’è fumo qui, Signore.” “Sì, Signore, dal fuoco.” The night did not pass without our apprehensions being fulfilled regarding the nocturnal enemics which assailed our quarters, and next morning the Augean stable was cleansed by our attendants, to the perfect astonishment of the host, who appeared to glory in the antiquity of his dirt.

Bridge over the Osum River at Berat

(Photo: Hendrik Reimers, 1914).

Unable to sleep I arose with the sun and accompanied Mustafà to the city. In passing over the bridge, as well as in the suburbs, we met several parties of Turkish ladies riding out on horseback to take the morning air: they sat astride upon the saddle with their feet in stirrups, whilst a male attendant generally walked before each horse and carried a short stick in his hand. Some of them were unveiled, not expecting, I suppose, to meet the polluting eyes of a Christian at this time in the day. Throughout Upper Albania it seemed as if a certain colour predominated in female apparel as connected with particular districts. In Argyro-Castro this was a light straw colour: here at Berat it was blue; in which latter city a fashion also prevailed in the head-dress of the women which was very singular and striking: this consisted of a cap or bonnet, nearly two feet in height, in the shape of a bishop’s mitre; it was made generally of blue cloth, well stuffed, and fastened under the chin by ribbons.

The bazaar, which is an extremely handsome and spacious quarter of Berat, lies close to the river and abounds in all sorts of articles brought from Constantinople and the large towns of Macedonia, as well as in foreign goods which are imported through the sea-port of Avlona. It was now full market, and the appearance of a foreigner excited no small degree of curiosity. Mustafà however, who is of Macedonian origin, was soon recognised, and kissed upon the cheek according to custom by many old acquaintances, and before we thought of returning to our lodgings, his brother, who had heard of his approach, and made a journey from the city of Monastir to meet him, alighted from his horse at the door of a han. The affectionate embraces and tears of joy shed by these two semi-barbarians at this rencontre were so affecting, that I felt loth to separate them and returned home alone.

Orthodox Church of the Holy Trinity in Berat

(Photo: Robert Elsie, November 2010).

Soon after breakfast our kaivasi rejoined us, and we proceeded to pay a visit to Hussein Bey, the eldest son of Mouchtar Pasha, who resided here in quality of his father’s caimacam, under the guidance of old Usuff-Araps, in whose fidelity the most unlimited confidence could be placed. The young bey was lodged in the old seraglio at the foot of the acropolis. He received us very civilly, and expressed a wish of rendering us all the services in his power: there was nothing remarkable either in his person or his manners, but his disposition seemed more amiable and his mind more cultivated than that of his father. Though not nineteen years old he had been married two years, but as yet remained without any progeny. Before our departure he intimated that some ancient remains might be seen within the fortifications of the acropolis, and made an offer of sending us upon his own horses up the heights. This we accepted and orders were given for the steeds to be brought immediately out of the stables where they generally stand ready caparisoned. Before we mounted we adjourned to the apartments of Usuff-Araps, but were unable to see him, as the old gentleman was indisposed. He was flattered however by our intention, for he sent us a magnificent turkey for dinner. In descending down the staircase we heard the prancing and neighing of the horses in the court, and observed two cream-coloured chargers, destined for Mr. Parker and myself, plunging about with an appearance of ungovernable fury: they were the most picturesque animals I ever beheld, and in their broad haunches and chests, thick curved necks and waving manes, small heads and eyes of fire, finely illustrated that splendid oriental description of the war-horse in the book of Job. Our ride was not the most agreeable one that we had experienced; nor was it very easy to sit these spirited animals upon a Turkish saddle, that precludes all pressure of the knee, which in our own style of riding contributes chiefly to a good seat. My steed became so ungovernable in ascending the acropolis, that if his groom had not ran and seized the bridle, I believe we should have both made a precipitate descent down a chasm many hundred feet in depth: when I dismounted, this vicious beast threw out his heels and then ran at me open-mouthed, when I only escaped by running up the staircase of the serai. Another source of alarm also occurred at this time: great repairs and augmentations being carried on in the fortress, the court was nearly filled with carts and sledges drawn by buffaloes: these animals have a decided antipathy to the colour of scarlet, in which Mr. Parker and myself, having just paid a visit of ceremony to the bey, were dressed. Pidcock’s menagerie broke loose would give but a faint idea of the noise and tumult which ensured. Some of the beasts even upset their carriages and broke their yokes in the exertions which they used to get free. To quiet this affay we made a speedy retreat into the interior of the serai, where we were courteously received by Ismail Bey, a rich Turk of Ioannina, the father-in-law of Hussein Bey, who was now upon a visit to his daughter. After the usual refreshment of pipes and coffee, and a very interesting conversation with this polite and high bred Osmanli, he accompanied us through the seraglio and fortifications, pointing out a hill, about 500 yards distant, from whence Ali battered these works in the time of Ibrahim Pasha with four pieces of ordnance, and forced him to a capitulation. Ibrahim had not recourse to this measure before the balls began to penetrate into his own apartment, where we still saw the vestiges, which are designedly preserved. In our egress from the grand entrance of the citadel, we observed some massive building of the ancient Greeks, which formed the lower part of its construction, and extended to some distance in the adjoining walls. It is a rough species of Isodomon, and the blocks employed are of immense size. From hence we made a circuit of the hill, to which the title of acropolis well applies, since a small town is contained between its lines of circumvallation, wherein are many Greek churches of the Lower Empire: indeed I entertain very little doubt but that anciently the whole city occupied this site, and that the lower town is an addition since the Turkish conquest. What the ancient city was called, I confess myself unable to decide; nor it is at all certain at what time it received its present appellation. It is mentioned by many of the Byzantine historians under the title of Balagrada and Balagrita, and is now called Arnaout Belgrade, to distinguish it from the celebrated city of this name upon the banks of the Danube. The Greek emperors sometimes made this their head-quarters when they came to chastise the revolted Albanians or other lawless tribes among these districts. It is a most important post, the key of all this part of the country. The great Scanderbeg himself failed in his attempts to recover it from the Turks, though he encamped against it with 8000 horse and 7000 foot, amongst which was reckoned a strong corps of Italians sent by Alfonso King of Naples, “men skilful,” as the historian observes, “in the assaulting of walles and holdes.” The defeat he suffered here from the Pasha Sebalias, wherein he lost nearly all his Neapolitan auxiliaries, was amongst the severest by which his almost uninterrupted career of success was checked. The battle was most bloody: Musache de Thiopie, brother-in-law of Scanderbeg, being killed, with 3000 foot and 2000 horse; though Scanderbeg in some measure restored the fortune of the day by pouring down from the hill, on which he was encamped with a select corps, upon the rear of the victorious enemy, and slaying with his own hand two desperate Osmanli captains who had sworn his destruction. The bodies of the Christians slain in this battle were shamefully mutilated, and their heads carried in triumph to Constantinople. Berat was conquered by the great Sultan Amurath II., since whose time it has never been freed from the Ottoman yoke.

After having surveyed the fortifications of this citadel and enjoyed a view of the splendid scenery which it commands on all sides, we remounted our steeds at the door of the serai and descended down the acropolis: I own I had no great zest for mounting my Bucephalus, but amongst these people it is quite necessary to shew no signs of fear. When we had thanked Hussein Bey for his civilities, and distributed the customary presents amongst his retainers, we took a walk through the city, which is large and contains thirteen Turkish mosques: from thence we strolled through the beautiful cemetery represented in the annexed plate: beyond this are numerous and extensive gardens bordering on the great plain, which extends to Valona on the west and very near to Albassan [Elbasan] and Kavaia [Kavaja] on the north: we observed large droves of buffaloes cropping the herbage, and cooling themselves in the river, which is here about as broad as the Thames at Richmond.

On our return home we dined sumptuously upon old Usuff’s turkey, and in the evening received visits from some respectable Greek gentlemen: they were the only persons we had met with who spoke with any degree of satisfaction at the government of Ali Pasha; but they contrasted it with the turbulent insecure state in which they existed, owing to his aggressions, during the latter years of Ibrahim’s reign: besides which, it is certain that the despot’s views still turn northward, and that he is very anxious to gain possession of the pashalic of Scutari; the advantages therefore of a good character in this part of the country are not to be overlooked. We retired to rest early, having a long journey to perform next day in the direction of Klissura, Premeti and Konizza, up the valley of the Voïussa. I now gladly use the kind permission of my friend, Mr. Jones, to take an extract from his MS. journal, feeling confident that in this I do but anticipate the wishes of my reader.

* * *Berat, Oct. 2d, 1815. – The pasha having sent horses, according to his promise, we left Berat about nine o’clock in the morning for the ruins of Pollina, the ancient Apollonia. Below the hill, upon which stands the great fortress and seraglio, we passed through a Turkish cemetery, containing an astonishing number of tombs, under the shade of which the Albanians, employed upon the works, were eating their breakfast. Our road lay in the direction nearly N.W. until we crossed river, which is the Apsus of antiquity. After this we entered into an immense plain covered with all kinds of cattle, buffaloes, horses, sheep, and goats. At about the middle of this plain we again reached the banks of the Apsus, and followed its course till it took a sudden turn to the N. W. It was our intention to have reached the monastery of Payane [Pojan], which lies close to the ruins, this evening, but night coming on, we took up our quarters in a wretched village called Shaelk [Sheq]; our lodging, which was the best in the place, was a miserable hut built of the stalks of Indian corn, twigs, and mud; three large openings in the wall serving for door, windows, and chimney. Early next morning we left these quarters and reached the monastery in two hours, where an old monk undertook to be our guide to the ruins of Apollonia.

The ruins of Apollonia

(Photo: Robert Elsie, October 2012).

A single Doric column forms the sole vestige of this once great and populous city, the theatre of Caesar and Pompey’s contests, and the place of Augustus’s early education. A few other relics remain in the walls of the monastery, and in some Turkish sepulchres on the road from Berat there are several inscriptions, but all sepulchral. In every map which I have seen, Pollina is placed too far from the sea, and too near to the Voïussa. From hence we pursued our course in a southern direction through the small village of Lievano [Levan], crossed the Voïussa in a ferry-boat, and proceeding along a fertile plain, arrived at Avlona [Vlora] in the evening. This town contains about a thousand houses, almost all Turkish. From hence we crossed over the hills just behind the town, and proceeding in a S. E. direction, came to the river Susitza [Shushica], a considerable stream, nearly as large as the Voïussa, into which it flows just below the village of Armen [Armen]: this is probably the Celydnus of antiquity; it takes its rise in the mountains of Kimarra. From the village we proceeded nearly in an eastern direction, till we came near to the Voïussa, and then turning to the right, arrived at the village of Selenitza [Selenica], about half a mile from which is the principal shaft of the great pitch mines, which bring in a considerable revenue to the vizir. Placed in the noose of a rope I descended down this shaft: it was about forty feet deep, and of recent formation. Advancing near two miles further up the Voïussa, I came to a spot of ground devoid of all vegetation, from whence proceeded a strong sulphureous smell. My servant struck a light with which I set fire to the gas that issued out of the crevices; the flame spread rapidly in different directions, and burned with great fury at the time of my departure. I perceived a number of bees and reptiles lying dead upon the ground near those crevices. Close to the spot are three oblong blocks of stone worked with great nicety, which had been turned up out of the ground by people digging for sulphur: these probably are fragments of the ancient oracular Nymphaeum. From the village of Romous [Romës] in this vicinity, we proceeded through Carbonara [Karbunara] to the ferry of Lundra, for the purpose of crossing the Voïussa and visiting the ruins at Gradista [Gradishta] on the right bank of that river. This ancient city surmounted the summit of a lofty hill, round which the outer wall may still easily be traced: a transverse one of later date runs across the site formed of small stones and mortar. In a westerly direction from this transverse wall are the remains of a temple, and on turning southward I found a long subterranean chamber of an oblong shape, but narrow in proportion to its length: at no great distance from the southern wall of the city stood evidently a theatre; the angular corners of the proscenium are visible, and the ground is seen rising in a graduated manner.

From Gradista I meant to have proceeded by the direct road to Tepeleni; but my Albanian guard had lately taken a wife, and as he had not seen her for some time, I indulged him by passing the night in his house at the village of Fratari [Fratar], on the mountains which lie to the left of the road. The customs of the country did not permit me to see the lady who was the object of our visit.

The Bistrica River near Syri i kaltër

(Photo: Robert Elsie, October 2012).

In the course of the evening several of his Albanian friends came to see him, in their large shaggy capotes, with long pipes and white staves in their hands. Some of these were the wildest looking fellows I ever beheld. A wandering dervish passed the night with us. He was above eighty years of age, wore a very long white heard, and was extremely talkative till about the hour of going to rest: then he assumed a sudden seriousness preparatory to his prayers. I could not help feeling a degree of respect mingled with pity, when I saw this venerable old man go through his ablutions and prayers: he performed part in silence and part loud enough to be heard, repeating the name of Mohammed two or three times with great solemnity.

From Fratari we did not arrive at Tepeleni till the second day, as the roads became extremely bad on account of a heavy fall of rain. The vizir is fortifying this town and has already cut a deep trench at the back of it. The direct route from hence to Ioannina is through Argyro-Castro and Delvinaki; but as the plague was now raging at the former place, I deviated to the once beautiful city of Gardiki [Kardhiq], now utterly overthrown or rendered desolate by the vizir, who has vowed that it shall never again become the habitation of man. From hence I continued my route between two high mountain ridges till I descended into the plain of Delvino [Delvina]; but here also I found the plague broken out and the city surrounded with troops to prevent all communication. The sick were in a kind of barrack on the hills behind the town. Being told there was a palaio-castro or some ancient ruins at the village of Phenikè [Phoinike/Finiq], about half an hour distant, I proceeded thither, sending my guard forward to inquire if any symptoms of the plague were known to be in the place. Upon receiving assurance that all was right, I determined to take up my quarters there for the night. Soon after my arrival a large fire of wood was lighted at the foot of the hills, and a goat roasted whole to welcome me. The whole village formed a circle round the fire and I seated myself amongst them. It was a beautiful moonlight, and in spite of that unwelcome visiter the plague being so near, I could not help enjoying the singularity of the scene.

Early next morning, being told there was a curious fountain on the eastern side of the hill, I ascended thither; but found in it nothing extraordinary, though the inhabitants assured me that it had a regular increase and diminution daily during the summer. From hence I ascended the hill by a steep path covered with fern and briars to an ancient wall, which highly gratified my curiosity. I found it in a very perfect state to the distance of sixty yards in length, and twenty-three feet in height. The stones employed in its construction are immensely large. I measured one which was seven feet long, twenty-one feet high, and three feet two inches broad: another was nine feet eight inches in length by seven feet two inches in breadth; and in one spot three stones alone form a piece of wall thirteen feet in extent. These blocks are cut with great accuracy and seem as firm as if they had been placed here but a few days. In the interior, the ground is almost on a level with the top of the wall. I entered by what appears to have been a principal gateway, and soon observed two octagonal columns about ten yards distant from each other, the fragments of a fluted pillar, and some other relics. The area is covered with briars and herbage, and exhibits evident marks of its having been occupied at two distinct periods by more modern inhabitants than the ancient Hellenes. Thinking it probably, from the appearance of the stones, that some inscription might be discovered, I procured assistance from the peasants in removing several, and discovered one inscribed with the following word in large characters:

ΑΜΒΡΑ

ΚΙΩΤΑExcavations here in all probability would be very successful. Not far distant I found two other octagonal columns standing, like the others, erect, and about two feet in height, with many other architectural fragments, and foundations of several edifices. There is also what I take to be the site of an immense theatre, facing the west, where the ground is seen to rise like a succession of steps one behind the other. The wall is most perfect on the eastern side of the hill along its brow: it appears also at intervals on the western side: the whole circumference seems about two miles: in some parts it is scarcely thirty yards in breadth, and is intersected in its sides by deep hollows: at its north-west extremity (for it runs north-west and south-east) it is lower and terminates almost in a point: towards the other end and on each side it is so steep as to make the ascent extremely difficult. The whole rises quite abruptly near the centre of the plain of Delvino; at the south-east end of which is the little village of Pheniké. This situation is assigned by Signore Psalida to the ancient oracle of Dodona; but the only features which appear to correspond with Strabo’s account are the following: 1. The plain, very marshy, particularly towards the south, where two rivers lose themselves in a considerable lake, viz. the Bistritza [Bistrica], which flows from Mourzina [Muzina] five hours south-east from Pheniké, and the Kalesproti which runs on the west side of the hill. 2. The hill itself, surrounded on all sides by magnificent mountains, except towards the south where the sea and the island of Corfu are seen above the low eminences. 2. The fountain on the east side of the hill.

The epithets δυσχέιμερος and ἀιπυνωτος, which Homer and Aeschylus apply to Dodona well accord with this situation: there are many trees, principally willows and poplars, on the plain; but I could discover no traces of the prophetic oaks.

Eagle carved into the outer wall of the

Orthodox Church of St Nicholas at Mesopotam

(Photo: Robert Elsie, March 2008).From Pheniké I went along the banks of the Bistritza to its source. I visited on my way an old Greek church, dedicated to Saint Nicolo, distant about one hour from the village; it is evidently constructed with materials brought from the ruins: the interior is supported by granite columns some of which are twenty inches in diameter, but others less: they are not more than seven feet in height; in the walls are several blocks sculptured in relief with figures of a lion, an eagle, &c. well executed. Amongst others I found one with an inscription defaced, but terminated by the word ΧΑΙΡΕΤΕ “Farewel!” The source of the river is just below the village of Mourzina. Half issues out of a rock in at least fifty streams of the sweetest and most transparent water: the other half proceeds from a pool, which appears very deep, as the surface is not ruffled by the least ebullition. I was shewn at another place a round hole in the rock, from which a few years ago water also flowed; but this is now dry. The rock appears of limestone; the water issues out in most places with great velocity and forms a stream as large as the Avon at Bath.

From hence, passing through Mourzina, we proceeded between two immense ridges of mountains branching off from that which forms the western boundary of the great vale of Deropuli, whose scenery soon burst upon our view, exhibiting a prospect of unparalleled magnificence in its noble mountains and its numerous towns and villages. We passed across it to the village on its eastern side, but the inhabitants would not receive us when they heard we came from the neighbourhood of Delvino; we were obliged therefore to keep on our course, and as it was a fine moonlight night, and we were travelling under a Grecian sky, we scarcely regretted our disappointment. We rested at Pondicatis [Pontikátes], and next day reached Zitza [Zítsa], a place celebrated in the stanzas of Childe Harold, though I think his encomium is much too lavish. The view is certainly fine, but far inferior to the vale of Deropuli and many others of Epirus. Here is made the best wine in Greece, and this was the time of vintage. All the wine is made out in the fields, where the grapes are put into large casks and trod upon by men bare-footed, till the juice is quite expressed: it is then carried in goat skins to the village, put into barrels, and left to ferment and settle: it is removed in this manner four or five times before it is put into the cask for drinking.

View of Janina (Ioannina) in Epirus

(Drawing by Charles Cockerell, 1813).

In my way from Zitza to Ioannina I passed through the village of Protopapas [Protópapas], which some consider as the site of Dodona: I made diligent inquiries for ruins, but could find none. The approach of Ioannina from the north appeared to me much finer than that from the south, its grand seraglio, fortress, minarets, and cypress groves being seen from this quarter to great advantage. The last few days I passed in Ioannina were rendered melancholy to me, from a very distressing circumstance. On my arrival, October 12th, I was informed that two English gentlemen were in the city, one of whom lay dangerously ill. I went immediately to visit them and found the sick person to be a Mr. King whom I had known at Corfu, and from whom I experienced many civilities. He was chaplain to the Ionian forces, and had come with his friend Captain Scriven of the Royal Artillery, to see Ioannina and pay a visit to Ali Pasha. Great alarms were expressed, for fear his disorder might be the plague, and I was earnestly requested to leave this place; this however I could not consent to do, especially as I perceived Mr. King’s illness was the malaria fever, which he, as well as his servant, had caught at Prevesa. He was apparently about forty years of age, and possessed of as strong and robust a constitution as I ever met with; but he died in my arms on the 15th, and I buried him next evening in the cemetery of the Greek church of St. Nicolo. On the following day I procured a stone slab, which, after I had inscribed upon it the name and titles of the deceased, I placed at the head of his grave. The day before I quitted Ioannina, I visited the vizir in company with Captain Scriven. The chief subject of our conversation related to the unfortunate death of Mr. King: he appeared affected by the event; but whether this proceeded from humanity I will not pretend to say. The same day we also paid a visit to Salee Pasha, the vizir’s youngest son. He had lately received two tails from the Porte and been created Pasha. He received us sitting like his father, and asked us several pertinent questions respecting our own country and our opinion of Albania. Next day, I departed for Athens over the mountain barrier of the Pindus.

CHAPTER XIDeparture from Berat – Route to Klissura – Description of the Town and Fortress – Fauces Antigoneae – Route to Premeti – Lustral Eggs – Town of Premeti, Serai, and curious Rock on the Bank of the Voiussa – Interesting Route to Ostanitza – Castra-Pyrrhi – Ostanitza – Route to Konitza – Picturesque Situation of that City – Mountain of Papingo – Albanian Governor’s Hospitality – Ascent to the ancient Fortress – Beautiful Crystals found on the Hill – Route to Mavro-vouni, and from thence to Ioannina […]