| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

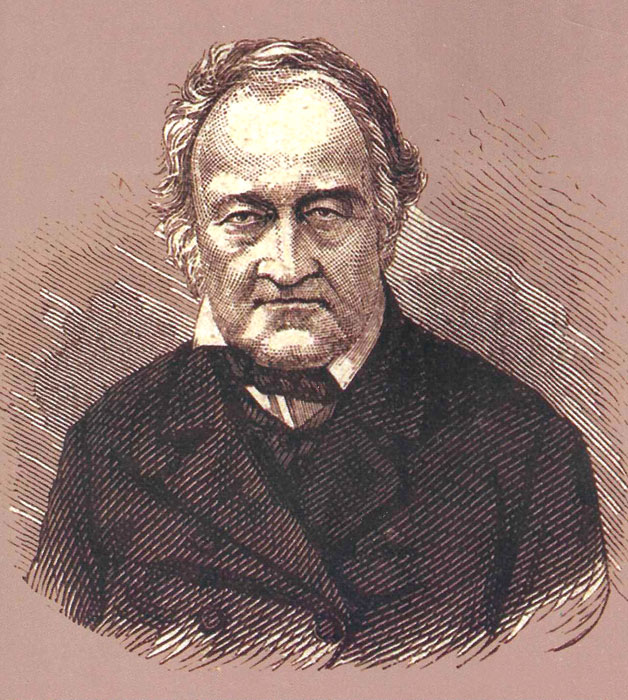

Ami Boué (1794-1881).

1836

Ami Boué:

Journeys through Kosovo

in European TurkeyThe German-Austrian geographer, Ami Boué (1794-1881), stemmed from a Huguenot family from Bergerac in Dordogne (France) that moved to Hamburg in 1705. He was born in Hamburg and went to school there and in Geneva. Boué studied medicine in Edinburgh between 1814-1817 but turned increasingly to geology and botany. After finishing his studies in medicine, he lived primarily in Paris where he was a founder (1830) and later president (1835) of the French Geological Society (“Société Géologique de France”). Having received a substantial inheritance from his parents, he travelled throughout Europe, primarily in Germany, Austria and the Balkans. In 1841 he settled in Vienna where he became an Austrian citizen and a member of the Academy of Sciences (1848). Ami Boué’s travels and research in European Turkey, a region that was little known at the time, had a profound influence on subsequent generations of scholars throughout Europe. Mention may be made in particular of his monumental four-volume work, “La Turquie d’Europe ou observations sur la géographie, la géologie, l’histoire naturelle, la statistique, les moeurs, les coutumes, l’archéologie, l’agriculture, l’industrie, le commerce, les gouvernements divers, le clergé, l’histoire et l’état politique de cet empire” (Turkey in Europe, or Observations on the Geography, Geology, Natural History, Statistics, Customs and Habits, Archaeology, Agriculture, Industry, Commerce, Various Governments, Clergy, and the History of the Political State of this Empire), Paris 1840; and the two-volume “Recueil d’itinéraire dans la Turquie d’Europe: détails géographiques, topographiques et statistiques sur cet empire” (Itineraries in Turkey in Europe: Geographical, Topographical and Statistical Details on the Empire), Vienna 1854. The latter volume, from which the following extracts are taken, include the itineraries of his voyages through Kosovo in 1836-1838.

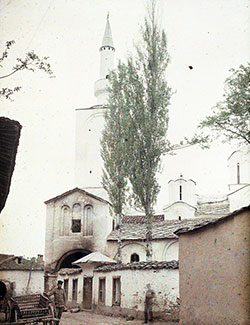

The Serbian Orthodox Patriarchate in Peja/Peć

(Photo: Robert Elsie, January 1996).

Peja

Ipek (Slavic Pecha, Albanian Peja), which is 17 hours from Novipazar [Novi Pazar], has a very agreeable location and is sheltered to the north by an enormous screen of mountains. Emerging from the profound gorge of Streta Gora, the Bistritza [Bistrica] river passes through the town between the mountains of Peklen (also pronounced Paklen) and of Koprivnik for about half a league. Its swift-flowing waters serve to turn the mills and carry away the refuse. Several streets are flooded by the branches of this torrent and the narrow sidewalks serve here as bridges. What is more, this ancient residence of the Serbian patriarchs looks very much to be on the decline because there are no more than 2,000 houses or 7,000 to 8,000 souls, most of whom would seem to be Serbs of the Greek [Orthodox] religion. This information gathered on site differs from the numbers collected by Dr Müller who notes 2,400 houses and increases the number of inhabitants to 12,000, claiming that most of them are Muslims and that there are no more than 130 families of Greek religion and 20 families of Roman Catholic faith. He nonetheless notes that the Slavs form the majority nationality, which makes one suspect that many of the latter simply claimed to be Muslims in order to be better treated. According to him, there are only 62 Turkish families, 100 Albanian families and 28 Zinzar [Vlach] families. If the Muslim population predominated, it would be difficult to explain the paucity of mosques. We saw only three, one of which to the northeast, one near the market, and one near the exit from town to the southwest, on the road to Detschiani [Deçan]. In his desire and in the custom of the Slavs to exaggerate their numbers, the monk Jurišić gives Ipek 4,000 houses, of which 700 to 800 are Serbian and of Greek religion. The shops, number over 960 (?) according to Dr Müller, are all to be found in four streets that make up the market. The streets and the houses are shaded here and there by vine arbours. There are two or three inns, of which the one near the entrance to town on the Djakova [Gjakova] side is the best because it has several clean rooms on the upper floor.

To the northwest, a quarter of an hour from town is the Serbian monastery of Saint Arsenius, the ancient residence of the Serbian patriarch, which has been converted into barracks. It is situated on a small promontory dominating the town and is surrounded by thick walls and trenches. The building actually contained three churches under one roof, one large one and two small ones. One of them is the Church of the Assumption of Our Lady and another one is the Church of Saint Demetrius the Martyr. It has three domes and is covered in lead. At the entrance to the church there are three columns in stone and two in white marble. The konak of the pasha with two wings is situated at the extreme northwest of the town in Pehlivan Meidan. It is a stone building with one upper floor, surrounded by walls and with a large gate. In front of it, there is a lawn with a few trees and a mosque, to which a school or medresa has been annexed. The pasha also has a country home or one for his harem located at the entrance to Streta Gora and another one near Novo Selo.

The pashalik of Ipek, once with a semi-hereditary administration, is simply part of Doukadgin [Dukagjin], and makes up the districts of Ipek, Djakova, Has or Hassi [Has] and Kéroubi (?). It covers primarily the northern part of Metochiia [Metohija] and part of the mountains to the northeast where only villages and hamlets are to be found. Dr Müller gives it a population of 65,000 souls, of whom 31,000 he says are Christians of Greek rite.

The Pasha Abdularasa speaks Serbian and Turkish and stems from a Brenović family of Bosnia. He received us hospitably. His apartments looked much better than those of the pasha of Novipazar. He gave orders that we were to be lodged with a well-to-do individual in town who owned two houses. As such, we were obliged to leave our Serbian inn. The pasha’s kavass knocked on a few doors and the first people to open up were forced to help transport our baggage. We had the opportunity of visiting the pasha’s nephew, an ailing lad who was suffering from hydrocephalus and was wrapped in sort of hammock with an enormous, heavy gold-embroidered canopy.

We climbed to the summit of Mount Peklen which is the nearest peak to town. The road leading up to it was the one to Rougova [Rugova], a village of 1,200 Muslim Albanians of the Klementi [Kelmendi] tribe who, a short while ago, had been Catholic. It is situated at six or seven hours from Ipek, beyond a spur of Mount Haila or Hailasi [Hajla] (the Albanian word is haliki, meaning rocky) at the foot of Schtedim [Shtedim]. From there, one can continue over to the Lim river and the basin of Plava [Plav/Plava] through a deep valley located between the market town of Plava and the valley of Velika. There is also a village called Trebigne [Trebinje]. This route is much used in summer by peasants and their pack horses coming and going between southern Bosnia and the high basin of Upper Albania. Although their clothing was reduced to what was strictly necessary and some of them went barefoot and their red caps were very worn, the candid faces of these beings – savage-looking to a foreigner – resembled those of the Swiss mountaineers. […]

Deçan

We paid a visit to the famous Serbian monastery of Detschani that is located two and a half leagues southwest of Ipek. The leader of the Christians of Ipek gave us one of his men as a guide and we left our Tartar at home. Leaving town, we passed by a mosque where a clergyman was in prayer. He made a sign as if we were to leave him alone or that our presence offended him. On our return, some mischievous boys threw apples at us, a sign that religious fanaticism has not been entirely overcome in these remote regions of Turkey.

The road from Ipek to Detschiani or Detschani follows along the foot of the mountains for about a quarter of a league from them and passes through three Albanian villages called Striatz [Strellc] (Kiepert calls it Striotza), Lioubouscha [Lëbusha] with the ruins of the Church of Saint Elias, and Lioubonitch [Lybeniq]. We were told that the second village, about half way along, was the site where 23 of the pasha’s soldiers were killed by the inhabitants last year (1835). As one can see, the Albanians detest the Turkish administration. Nonetheless, the Albanian women to whom we ventured to say hello on passing by, responded politely, contrary to oriental custom. The surroundings of the monastery and even the entrance to the valley of Detschani are hidden from view by a large forest of chestnut trees, the Gora Koschtanova (Kestenova). The Albanian village of Detschiani is half an hour to the east of the monastery on the Bistritza. The quickest way to the monastery is to cross a small wooded ridge, from which one is surprised by the panorama of a fair, small and verdant basin where the church and monastery of Detschiani are hidden at the southern side of a hill covered in oak trees, at the foot of a rocky mountain called Pliesch. Further to the south there are mountains covered in pine trees with low ridges bearing the name Detschiani. The livestock of the monastery graze here in the summer, a quarter of an hour away. To reach the gate of the monastery enclosure, one must cross the Detschianska Bistritza [Lumbardhi i Deçanit] river that flows from northwest to southeast and has a very stony bed. The monastery consists simply of one building with an upper floor that is very thin in appearance. The beautiful marble church, however, is a monument that could easily be found in any of our cities. There are also two smaller churches, one dedicated to Saint Nicholas and the other to Saint Demetrius the Martyr.

There were only five or six monks at the monastery. The igumen was paralysed and had been bedridden for a long time. He complained about the monastery’s debts caused by continuous Turkish exactions. The thought worried him terribly, as he said, because the faithful might stop paying the interest and reimbursing the sums borrowed. This poor monk died that year and in 1837 it was a new abbot we met there. Within the monastery there is a small vegetable garden and outside the property, there are mostly fields, pastures and huge forests.

To the west of the monastery is a wasteland of woods and mountains almost ten leagues in length, through which one can reach the high valleys of the Prokletija and even Shalia [Shala] and Gouzinie [Gucia/Gusinje]. […]

Peja to Prishtina

The road from Ipek to Prischtina [Prishtina] crosses the plain stretching from west-northwest to east-southeast. It is cultivated here and there, but mostly covered in pastureland and groves of trees. To our right and in front of us there were hills called Kraljania (of the king). At one league from Ipek we passed successively Plavian [Pavlan], Zachatschi [Zahaç] and Labian or Lebian [Llabjan]. This may be the settlement referred to by Dr Müller as Lebous. He also mentions a Muslim village to the south of Ipek with the curious name of Voksch [Voksh] (20 hours), and three leagues away is Tzrkva [Svërka] (church). A poor old Serbian woman cried out as she offered us some water: “You have finally come! The Christians here are waiting for Prince Milosh as their Messiah, to deliver us from our suffering!” Seeing us surrounded by Serbs, she took us for one of them. Instead of reacting in anger, the kavass of Ipek simply replied: “The old woman is mad!” This country is probably quite a disagreeable place to be for the servants of the pashas because our guide took two pairs of pistols and a rifle with him. To the south of Doubaschar, several little hills and oak forests lead the traveller to Novoselo and then to the Drim [Drin] river that one crosses on a wooden bridge. Drsnik [Dërsnik], at six hours from Ipek, is located on the opposite bank at the foot of some little terraces.

To get from there to Prischtina, one proceeds across some wooded and rocky plains to the west of Drsnik, the first of which is called Drsnikbari and the second Brtschevabari. Veins of Eocene limestone are exploited here to roof the houses in the surroundings. At two leagues from Drsnik, we arrived at Iglareva [Gllareva], where there was pastureland followed by forests and some rather soggy meadows. Having passed through the villages of Kieva [Kjeva] and Mletjan [Mleçan], we continued through a very wide valley, consisting mostly of meadows. In the distance to the north were several low ridges, the highest of which was Komoran. We did not go through the village of Loschitza [Llazica]. Finally, without even realising that we were climbing, we arrived by a branch of the valley at the remote inn of Lapouschnik [Llapushnik] which is located at an altitude of 1,457 feet or about 400 feet above the White Drim. […]

The inn of Lapouschnik consists of a large barn covered in flagstones, in front of which is a rectangular, cobblestone courtyard. It is closed off at the front by a wall and gate. On each side is a square building with an upper floor, in one of which the main floor is used to store the provisions of the innkeeper and for the oven. The upstairs room on each side has five little windows with wooden bars. The room where we spent the night was piled full of objects such as sacks and matting.

Just after Lapouschnik, we crossed the Drnitza [Drenica] river on a wooden bridge at 1,447 feet in altitude. It flows slowly through the black clay soil. The mention of a village called Janievo as a geographical point on this river is doubtful. If the village exists, it would be nearer to the bend in the Drnitza where it enters the plain of the Sitnitza [Sitnica]. To get down to the water from the inn, we had to climb a bit and cross several low wooded ridges of oak trees that separated us from the plain of the Sitnitza. These ridges all run from north to south, increasing in height from west to east and have little ravines in them which are, however, no impediment to oxcarts. There are numerous rosebushes in the hedges, as in Serbia. […]

Pastures and crops cover the plain of the Sitnitza. Here and there, we could see villages without any trees. The descent from the summit was gradual and did not last more than a quarter of an hour. We reached the village of Vragoulia [Vragolia] (perhaps from Vragolije, devil’s work?), and then crossed the village of Slatina [Sllatina] and finally the Sitnitza river that flows slowly here in a south to north direction and irrigates the whole region. A little farther on, we forded the Schaglavitza [Çagllavica], a small tributary of the Sitnitza. We could see villages to the north and southwest, but our attention was more drawn to the magnificent mountains of Kopaonik in the form of a magnificent amphitheatre and their foothills. To the south-southwest rose the low mountains of Katschanik [Kaçanik] to 6,400 feet, with the elegant cone of Lioubeten [Luboten] at the eastern edge of the Schar [Sharr] range.

The oval plain of the Sitnitza is nine to ten leagues long, stretching north to south, and three leagues wide, at an altitude of over 1,400 feet. It is bounded by low mountain ridges to the east and to the west. Prischtina is located in a winding valley separated from the plain itself by a small ridge open only to the southwest. In the upper part of this little valley and above Prischtina there is a nice spring in the midst of alluvial clay that covers the older ground. The spring forms a small basin for the laundry women and flows through the town from northeast to southwest. Before one reaches the town, there is a creek called Breitche or Brzé [Bresje].

Prishtina

Prischtina, called Pristina by the cartographers, got its name from prischt ‘tumour, boil’ because the hill to the west of the town has a sort of irregular promontory on the eastern side of the Sitnitza valley. This town is currently the largest in this part of Old Serbia (Stara Srbia), in which the Serbs include the districts of Novipazar, Metochie [Metohija] and western Upper Moesia right to the Macedonian border. At 17 hours from Ipek, this open town begins in the little valley and stretches eastwards in the form of an amphitheatre to the last slopes of a low ridge on a slant that looks rather unpleasant. The hills are covered in vineyards to the west and north, whereas to the east, the heights consist entirely of dry pastureland, the lower part of which serves as the cemetery for the town. Between it and the first houses are the remainders of a little trench and a low parapet that date from the time of the troubles in 1806 when bands of brigands terrorised the countryside. There is another cemetery to the northwest. Most of the streets are unpaved and irregular. They are cleansed by the rain and by the small above-mentioned creek. The butcher shops on the main street offer huge chunks of blood-dripping meat and entrails over a space of 20 paces, and brown dogs fight over the remains in the dreadful motley scene.

The Mosque of Jashar Pasha in Prishtina,

built in 1834 (Photo: Ismail Gagica).

The only noticeable buildings in Prischtina are a clock tower and twelve mosques, two of which are tall and round-shaped, painted in arabesques or in long sayings from the Koran. One small mosque was built by Jashar Pasha who held that post in 1837 and 1838. The bazaar is covered in boarding, and there is a café where the three main streets come together. The pasha’s konak is a large building constructed partly of wood. It has two wings and an upper floor with a large square courtyard, spacious corridors and wooden staircases, as is custom. One wing of the konak is painted in arabesques. It is connected over the road with the harem that is also a rather large house, mostly of wood, with closed window shades. The pasha’s divan has no glass windows. The windows are closed simply by folding in the wooden shutters. There were also swallows’ nests on the ceiling.

Prischtina seemed to me to have a population of about 7,000 to 9,000 souls, among whom there are a good number of Orthodox Serbs together with the Albanians and semi-Muslim Serbs. Mr Jurišić estimated 3,000 houses, a third of which were Serbs. This is the capital of the little pashalik that includes not only the basin of the Sitnitza up to Vouschitrn [Vushtrria], but also part of the surrounding mountains, the valley of the Drnitza and the upper reaches of the valley of the Lépenatz [Lepenc/Lepenac]. The only wretched settlements of note to be found here are Vouschitrn and Kratovo where there are ayans. All the other settlements, with the exception of the town of Prischtina, are villages and hamlets that rarely have even an agha. The population consists of Serbs and a few Bulgarians and Albanians, including a certain number of Serbs who have become half Albanians and Muslim for political reasons or through marriage. The Albanians live mostly in the south and southwest of the pashalik and the Serbs on the opposite sides. The total population is no more than 40,000 to 50,000 souls, and no less than 30,000

Prishtina to Kaçanik

The road from Prischtina to Ouskoub [Skopje] follows the last deforested slope of the foothills to the west of the Sitnitza basin. Half a league away, it crosses a little valley and a small hill on which is situated the hamlet of Schaglavitza [Çagllavica] surrounded by plum trees, and beyond this is the Slavic village of Lapouselo [Llapllasella] (Turkish Kadi-Keui [Kadiköy]) where an agha resides in a square house in the form of a tower with wooden extensions sticking out at the top.

The Lepenc and Nerodimja river

flowing together at Kaçanik

(Photo: Ismail Gagica).

In 1838 we simply chose the best Serbian house to stay at despite the protests of the women who claimed that they had nothing to offer us. When we had stored our baggage in the house and put the horses in the stable, we began poking about in the crates of these people and discovered some barley. As they could not hide the chickens, we had everything we needed. At this juncture, the master of the house arrived and we inveighed upon him to such an extent that he agreed to give us his barley, although he pretended he had just bought it. There was much stalling again before the agha consented to give us some hay in return for payment. The next day, he stayed at home all day claiming we might catch a fever. There were more unpleasant scenes with these Slavs who are so accustomed to being robbed by the Turks that simply catching sight of our money was enough to reassure them of payment for the supplies. Our Tartar could no longer contain his wrath because of their insolence and began to insult them. At one moment, the Serb seized his axe and was ready to respond with vigour if the Tartar continued to insult them. The Tartar fell silent for a while and later simply stated quite calmly that he would send a report to Prischtina and have some garrison troops sent around. This threat put an end to the bad mood of our host. He quietened down and we reached an arrangement. We were friends by the time we left in the afternoon.

To the east, we could see the convent of Saint Stephen or of Graschan [Graçan] near the place where the Gratschanitza [Graçanica] flows down onto the plain. This monastery was founded by King Milutin in the year 6730 since creation according to an inscription. It is built of stonework and has five domes, only one of which is large. At the entrance to the church there is a stone with a Roman inscription noted by Mr Jurišić. In 1838, the monastery had only three monks. At one league to the west of Lapouselo is the hamlet of Dodol and at one league to the north-northwest of this village is another.

The Gorge of Kaçanik in Kosovo

(Photo: Ismail Gagica).

Beyond the large village of Lapouselo one crosses a plain of black soil. One passes Labian and then Babousch or Babosch [Babush] to the west. Farther on is the Albanian village of Podrosch and then one crosses the Sitnitza river over a bridge. One then comes to a remote inn, beyond which the land begins to rise a bit. This is at one hour from Sazlia. There is a wooded hill here that stretches from east to west and separates the plain of the Sitnitza from the basin of Lepenatz or Lepenitza [Lepenc/Lepenac]. Having crossed a small slope at an elevation of 80 to 100 feet above the plain, one is on a wooded plateau at 1,580 feet in altitude. The soil is black here as if it had once been a marsh. Beyond this grove there are large marshes and a brook called Sazlia flows from north to south into the Lepenatz, whereas the source of the Sitnitza is a way to the north and north-northeast. One passes this brook over a stone bridge via the paved road, and one then arrives at the remote inn of Sazlia, located at five and a quarter hours from Prischtina near the marsh. It is a dismal place indeed. In 1836, this hotel consisted of a large barn with a very small chamber with a window, and three wooden huts for the hay and farming equipment. A wattle fence surrounded everything and the approach to the inn was extremely muddy. Not far away was a group of Bulgarian peasants camped out for the night who were taking three cartloads of cherries from Macedonia to Prischtina. The bridge of Sazlia is mentioned in Serbian folksongs because the marsh, located right on the military road, was something of importance, depending on circumstances.

Continuing our route, we soon passed by Varoschka Rieka flowing from north to south that seems to receive water from the Sazlia marsh and causes a watermill to turn. At one league to the right are the villages of Varosch [Varosh] and Sirnik. Further on, four hours before Katschanik, we encountered the creek of Nerodimlia [Nerodimja] that was called Porodimlia prior to the violent death of Tsar Urosh. In this area we noticed a good number of beautiful willow trees of a particular type. Finally at two and a half hours from Sazlia, we reached Novi Han which forms the southern border of the Pashalik of Prischtina. The inn occupies the lower part of a two-storey building, on the upper floor of which is a guard of gendarmes. This house is situated on one side of a square courtyard where there are two other simple one-storey cottages.

Five minutes away from there, we passed another guard corps belonging to the Pasha of Ouskoub that was deployed on a small promontory. The landscape was varied, wild and covered in undergrowth. The soil was gravelly and formed of alluvial deposits. This region was once covered in forests and its present barren state dates from 1806 when many brigands camped out there and also occupied Katschanik. Not even Prischtina was spared of these mobs who had the support of some of the ayans. At that time, a decision was taken to burn down the forests, both here and towards Vranja and in the Schar mountains between Prizren and Kalkanel [Tetova/Tetovo]. As such, in 1807, they put a stop to the brigandage for which the Katschanik trail had always been notorious, as can be noted in old Serbian folksongs.

We finally reached the bed of the Lépenatz which, full of boulders and gravel banks, seemed to have dug itself a channel through alluvial terraces. Its water was probably originally a lake stretching down to Katschanik. We saw very few crops, only here and there, and met some Turkish travellers as well as Serbian and Bulgarian peasants from Upper Moesia who were on their way to Macedonia to sell their harvest. They looked like Turks because they were wearing little turbans formed of white handkerchiefs, and some of them had pistols with them. There were also some women among them.

The approach to Katschanik (nine and three-quarter hours from Prischtina) is quite attractive. At first one catches sight of a mosque and a meadow because the little village itself is located behind them at an elevation of 1,350 feet. Climbing slightly, one passes the base of an old Serbian castle and enters onto a rather long road which forms most of this settlement along the western bank of the Lépenatz. There are also a few homes hidden on the opposite side of the river. On both sides of the river were hills covered in beech trees and, to the west, above the forests one could see the cone-shaped peak of Lioubéten (from the Albanian words liope ‘cow’ and tine ‘butter pot’). Mr Kiepert places it too far to the north, or Katschanik too far to the south. To the north rise low hills that paint a more agreeable picture to the eye, whereas to the south is the Mlad Planina, a hill compared to the peak of Lioubéten, that seemed quite insurmountable. Nonetheless, we pushed forth along the Lépenatz and entered the canyon. On the eastern bank was a ledge with a trail skilfully cut into it, but further on, the cliffs made the canyon narrower and narrower. The torrent seems to turn to the right. One must reach this point to see how the trail and the water make their way through the wooded cliffs in the mountains.

The inn of Katschanik was once perhaps clean and comfortable, but in 1836 all the rooms and corridors were run down and filthy. At least each of us could have his own room, a luxury we had not enjoyed since leaving Hungary. The innkeeper was a simple Turkish coffee seller and would have nothing to do with feeding us in the evening. Since our Asian Tartar was a lazy fellow, we had to send our servants out to get some food and had to cook it ourselves. I mention this to show the importance, when travelling in Turkey, of having a European Turk as one’s Tartar and to know the customs of the country because our Asian Tartar whom we treated as a servant and not as an effendi, that is to say, he was never invited to dine at the table or take coffee with us, only did what he was told and nothing more than that to please us.

As we wanted to climb to the top of Mount Lioubéten, we went to see the local ayan to ask him to give us a guide. He lived in a little place in the walls surrounding the old fortress of Katschanik. A ladder served him as a staircase and a tiny room with a bit of rug was his divan. His wife seemed to live in town. The ayan was away and his kiaja [steward] or alter ego told us he could not allow us to make such an excursion without permission from his chief, the Pasha of Ouskoub. Had we had a more agreeable Tartar with us, this misfortune would probably not have occurred because he would have passed us off as officials of the sultan rather than strengthening the ayan’s suspicions that we were spies. When this disappointing encounter was over, we had a look at the rest of the fortress and climbed up onto an elevation in the courtyard that was probably once the site of a tower. From this vantage point we got a good look at the mountains all around Katschanik and could see that from there, with large-calibre cannons, one could close off the road to Macedonia for which Katschanik is the gate on this side. The ayan’s men looked on with evident displeasure as we made our observations.

At a quarter of an hour from Katschanik, the road was completely blocked by a dolomite cliff through which a tunnel twenty paces long, ten paces wide and ten paces high had been dug. There was a plaque at the southern entrance of the tunnel that attributed the work to a vizier of Roumelia who lived in 1708 but, despite the rather pompous style of the Turkish inscription, it seemed rather doubtful that he was behind the good carriageway from Katschanik to Ouskoub, although it is possible. A little farther on, the Lépenatz receives the waters of the Kriva Rieka (wavy river) that flows in from the north-northeast, and a bit farther down another tributary flows into the river, this one being a large torrent coming down from the foot of Lioubéten. The gorge, which the Slavs call Klisoura, runs initially from northwest to southeast and then, at one and a half leagues from Katschanik, runs from east to west, but then finally assumes its original direction. For the first two and a half hours, we proceeded along a well-made trail on a slight slope along the eastern bank that made its way through woods and deep winding gorges, with the waters of the Lépenatz flowing below us. We kept right above the riverbed and advanced in good spirits along this splendid trail through the fragrant woods, adorned largely with dictamnus albus, orchids and a great variety of other flowers such as foxglove (digitalis lutea and purpurea), bellflowers, forget-me-nots, legumes, silenaciae and labiatae, etc. We were also surprised by the number of tortoises and their eggs. The natives do not eat or gather them and some of them in Katschanik could still remember with amazement the time in 1806 when Mr Hugues Pouqueville passed through and cooked them for dinner. On the Albanian coast they are caught and sold for export. At one and a half leagues from Katschanik we tried some acidic-tasting mineral water that welled from the ground near the banks of the Lépenatz, so much so that it floods the area in time of rain.

Gjilan to Prizren

Panorama of Gjilan in southeastern Kosovo

(Photo: Ismail Gagica).

To the south of the Morava is the village of Smorik and, climbing northwestwards at an angle to the mountains in the north, one arrives at the Serbian and Albanian village of Ropotov. In this settlement, the Serbs wear Albanian dress, as they do throughout ancient Rascia. A bed of dry leaves served as our bedroom in a small inn where we lacked none of the comforts of travel in Turkey. The road to Ghilan [Gjilan] rises immediately near an old Serbian church, now in ruins, and after hiking for about an hour, one reaches a plateau at 1,799 feet in elevation which offers a full view of the oval basin of Ghilan that is 350 feet lower and is about one league in length and half a league in width. It is well cultivated, in particular with corn, by the Serbian and Albanian population and, in the extreme southeast, has a farm surrounded by fair orchards and vegetable gardens. No need to mention that this is the property of the ayan of Ghilan. The rayah would not dare to own such property which in Turkish thinking is considered luxurious.

The carriage way passes through Ghilan or Ghilani, which is a settlement of about 1,500 to 2,000 inhabitants, mostly Arnauts [Muslim(?) Albanians]. Their disobedience to the orders of Sultan Mehmed was punished by the temporary exile of many of them to Thrace and Asia. From this point, the road follows a string of low and wooded hills to the basin of Prischtina [Prishtina] where one travels across a plain. We chose the shortest route but which his only suitable for horsemen. This would seem to be the one on the map.

One leaves the plain of Ghilan and continues eastwards along the hills to Pousti (desert) which is half a league from Ghilan and about 25 feet about the basin. From there, one follows up a torrent that flows into the Morava from the northeast. Then, north of this river, one crosses the eastern slope of some uninhabited mountains that are rather high. At the highest point, one is at 2348 feet in altitude. There, we came across a Serbian carriage carrying a corpse to its last resting place, probably some distant cemetery.

The road continues in a northwesterly or northerly direction. The hills gradually dissipate and one reaches a high valley where there are several homes and Albanian shepherds. To the north-northeast, there are peaks rising to 500 feet. They are probably what Mr Kiepert calls Vaschounja on his map. The pastureland of his barren valley then becomes a gravel mountain landscape, covered in low oak trees. In the midst of this wasteland, our Tartar companion was frightened for a moment when we came across three Albanians. From the heights, one can see Ghilan about three leagues away and the little Arnaut village of Novo Brdo (Novo Berda, the new mountain) two leagues to the northeast. It is situated in the indentation of a ridge about 500 feet over an observation point and at least one thousand feet over the plain of Prischtina. There are about one hundred houses, three or four mosques and a castle dating from the time of the Serbs, who were replaced by the Albanians. Below the manor, there is a rock cliff to the west. The area, which is little visited and surrounded by rugged mountains is ruled by an ayan. The surrounding mountains have few settlements and are covered in pastureland or low oak. Between Novo Brdo and the road to Prischtina there is a rather deep valley running from the northwest to the southeast, which means that one needs over three hours to get there. We did not come across the village of Labjan [Llabjan] noted by Mr Kiepert as being south of Novo Brdo. If he was right, there would be two settlements called Labjan, next to one another, the second one being situated in the basin of the Sitnitza between Lapousélo [Llapllasella] and Babosch [Babush]. But this does not mean that he is wrong. They are probably villages founded by persons having lived on the Lab [Llap], a river to the north of Prischtina.

The village of Janjeva/Janjevo in Kosovo

(Photo: Ismail Gagica).

Advancing along rolling hills, we crossed a valley stretching from north to south, then another stretching from east to west. Then, finally, we descended into a larger valley that stretches to the north and northwest, and then to the west. This valley bears the name Graschanitza [Graçanica] on the Vienna map. Slag left over from foundries indicated the nearby presence of iron ore and abandoned factories. In its western extension, this uninhabited valley narrows to form a wooded gorge which led us to a settlement with a Christian cemetery and several peasant cottages. This was the village of Janjevo, which was probably once much larger and is named after janj ‘poplar tree.’ Here, at two leagues from Prischtina, one leaves the valley, with the stream continuing to flow westwards, to reach the basin of Prischtina.

One can get to Prischtina directly from here, but one can also take a shortcut by climbing to the northwest sideways to reach a hilltop covered in groves of oak trees. This is probably the Janjina Planina that occurs in Serbian folksongs. One then descends into another small valley that leads to the plain of Kosovo and has a spring of water. From there, one continues in the same direction and cuts across several hills that stretch from east to west and that are covered in oak trees. The highest of these hills is 1,500 feet above the plain. Finally, one arrives at the summit, at the foot of which is Prischtina.

Winter scene of Mount Luboten in Kosovo

(Photo: Ismail Gagica).

There is a stunning view from the top, with the Schar [Sharr] mountains and their eastern peak Ljoubéten [Luboten] rising on one side, and the Kopaonik range in Serbia rising on the other. In front of the latter mountain range, the heights of that part of Upper Moesia fade, as do those that separate the basins of Prischtina and Ipek. It is only in the direction of this latter town and of Novibazar [Novi Pazar] that the horizon is full of mountain peaks that appear to the eye to be as high as Kapaonik.

At one league to the southwest of Prischtina, there is a farm and farther on is the little river of Graschanitza that flows gently through the black soil, the bed of a one-time lake that used to occupy this cavity. Still farther on, one fords the Sitnitza or Schitnitza which is no more than a gentle brook. Seeing it, it is difficult to understand why Sultan Murad could have needed all day to cross such a tiny stream before the Battle of Kosovo. One supposes that the Sitnitza was flooded or that historians have confused this river with the marshes of Sazlia [Sazlia] further to the south.

At two leagues from Prischtina there is a Bulgarian village called Skoula or Skoulan [Skullan]. We stayed there with a kind family that owned a compound of six or seven cottages, including sheds. These houses were made of wood or plaited branches and 12 people lived in them. From Skoulan it is a good half a league to the Muslim Arnaut village of Ribar [Ribar] at the foot of some wooded mountains, the highest of which, Goliesch [Golesh], we left to our northwest. We passed over the ridges stretching at 2,219 feet from west to east on a narrow gravel roadway through dense forests of oak that were extremely suitable for robbers. In the middle of the forest we came across several woodcutters. We then finally descended to the southwest along a dreadful path that snaked around a small ravine in the open valley where at 1,725 feet in altitude, there was a mill and several houses. We had decided to take our dinner there when a number of kiradjis [waggon-drivers] arrived, who terrified our Tartar.

This valley of the Tzernolieva Rieka [Carraleva/Crnolevo river], which Mr Hahn erroneously called Tserolera, runs from the northwest to the southeast and, here and there, from north to south. Its water flows into the Lepenatz [Lepenc/Lepenac] and not into the Sitnitza and turns completely towards the southeast. At the mill, the valley is overhung by a cliff and, rising along it a bit to the northwest, is the Albanian village of Kirmaleva or Tzernolieva [Carraleva] with several corn fields. The rest of the upper part towards the west is narrow, very wild and surrounded by oak forests. Despite this, the kiradjis pass through here from time to time which showed that the route was in use.

Suhareka in Kosovo, also known as Theranda

(Photo: Franz Nopcsa, 1903).

We continued to climb a bit until we reached the pass at 2,408 feet in altitude, where the Tzernlieva Rieka takes its source and where the waters divide, this stream being separated from that of Soua Rieka [Suhareka], pronounced Soha Rieka, meaning dry river. Two leagues before the pass, the Tzernolieva Rieka has a tributary coming in from the south and at one league from the pass there is another tributary coming in from the north. A bit to the south of the pass is an Arnaut hamlet called Doulié [Duhël] that consists of about twenty scattered houses covered in boards and without chimneys.

From the pass, it is another one and a half hours down to the little plain of Soua Rieka that consists of gravel and forms a long slope of low oak. The taller trees are quercus cerris in among the smaller ones of common oak (quercus robur). It is a carriage way. Another half an hour is needed to cross the plain leading to the village. The Soua Rieka stream passes through the village of the same name at 1,100 feet in altitude and turns to the southeast to take its source at the foot of the mighty peaks of Lioubeten that are joined to the heights of Doulié. This settlement is inhabited almost entirely by Arnauts, whose houses are mostly along the northern side of the stream. At a distance from there, there were several covered carts inhabited by Zingars [Gypsies]. Their buffalos were grazing around them and their dogs were waiting for an occasion to lunge at passers-by.

The inn of Soua Rieka is wretched. It is actually only a large shed, most of which is taken up by huge barrels used for making wine. This equipment belongs to the village and is stored with the inn-keeper where the grapes are harvested collectively and the produce is then divided up according to the size of the vineyards and the number of tubs of grapes brought in by each inhabitant. The rest of the inn is taken up by a hearth and a bit of room where people can sleep. There are no stables, such that the horse must stay outside in the covered part of the courtyard. The area of the inn around the hearth was occupied by a group of Muslim Albanians who took no notice of the presence of travellers, or if they did, then simply to look at us in contempt. Our Tartar was agitated and endeavoured to maintain his authority by engaging an Albanian in conversation. This fellow was a type of travelling official. Meanwhile, having stored our belongings on the floor in among the wine barrels, we considered getting to know the Albanian peasants and wanted to invite at least the oldest among them over for a cup of coffee. Our Tartar told us we were mad to have anything to do with such rabble. This compliment, probably understood by the Arnauts, put an end to any further conversation between us and them. This is a good example of how the presence of a Turk can hinder a European travelling in Albania because, if he had not been with us, we might perhaps have tamed these boors. But we could not do this without the consent of our Turk, and had we acted against his will, he would not have looked kindly upon us. His respect for us would have diminished in proportion to our familiarity with the Albanians. The Bulgarian innkeeper soon retired because he had a fever and left us to the care of his servant who did what he could to cook us a chicken. Aksham [evening] arrived and we were finally delivered of the devilish Albanians, but remained with our official. We had just finished eating when a full dinner was brought in for this fellow, which he invited our men to take part in. He invited the Tartar to eat with him and then set about drinking spirits. Having drunk his fill, he began pulling at his moustache and saying the most insulting things. He made fun of our man, his firman and his sultan. “If I like to drink a lot,” he said while prancing about, “it is because I know what I am doing and how much liquor I can hold, but this fellow here is a miserable brute.” Turning towards the Tartar, he said: “You talk about your watches and want a lot of money for them. I could easily have them from you. I would only need to go outside and call over two or three Albanians, and it would be you who would be obliged to pay me to take them. You pesevenk [pimp], your firman is just a piece of paper, and your sultan is a wretched giaour [infidel].” Fortunately, the Tartar was just as drunk and was unable to understand what the fellow was saying. Had he only been half as drunk, blood would have been spilled. The whole comedy that played out before us was beginning to irritate us when the servant of the innkeeper whispered into our ears that we were not to talk to the man too much because he was capable of anything. However, in defence of our honour, I must note that he said nothing insulting to us. He then went outside to lay down and added simply that he had found a better bed than ours. As soon as he was outside, the servant of the innkeeper shut the door and locked it with a wooden bar, as is custom, and the rest of the night was quiet.

The road from Soua Rieka to Prizren takes three and a half hours. Initially one crosses a low plain where there are several marshes. Then one passes along a stream flowing towards Soua Rieka from southeast to northwest. One then climbs up onto a slightly higher and broader plateau of the same type. From here, at about three hours from Prizren, one can see an Albanian village and some corn fields on the right side. The position was an excellent lookout to understand the structure of the Prizren basin on the northwest side of the Schar mountains. The Drim [Drin] river flows south of Djakova [Gjakova] through a wide gap in the hills at 600 to 800 feet in elevation over the valley. Having been joined by the Soua Rieka river and the Maritza [Lumbardh] river of Prizren, it flows down the valley or a gorge situated between the mountains to the south of Djakova and the lofty mountain of Hass [Has] or Schalé-Schoss [Shala Shosh?] that is cut off in the west by an enormous fissure running northeast to southwest. This is the gap that enables the White Drim to join the Black Drim.

At one league from Prizren one glimpses the cliffs of the Schar and at one quarter of a league from the carriage way is the Albanian village of Oritsché where there is a small stream coming in from the south and joining the Souha Rieka. It is possible that this is the Srebnitza (from srebro meaning ‘silver’) that Dr Müller referred to when he made mention of several Serbian villages on the plain, which he stated were to the northeast of Prizren. One continues apace through the countryside and, half an hour further on, one passes the village of Gloubitza or Loubitza on the right and a stream of the same name which, flowing from south to north empties into the Drim. A partially cultivated portion of the plain then leads the traveller to Prizren. […]

Prizren

Prizren, called Prizrendi by the Albanians and Pérsérin by the Turks, is constructed at 1,149 feet in altitude along the two banks of the river Maritza (Albanian Maratsch) and at the foot of the Schar mountains, such that part of the town forms a veritable amphitheatre, above which crowns an ancient fortress upon a lofty promontory, the residence of some Serbian kings. Surrounded by crenellated and well-kept walls, it occupies a large rectangular space to the west of the Maritza where it opens out onto the plain of Prizren. In the direction of the gorge of this stream, the limestone rock forms a cliff under the fortress, rising to a height of almost 200 feet. As the rest of the countryside is flat, cultivated in part and embellished with villages, the town of Prizren has a truly magnificent position. In order to appreciate it, one must not see it from the surrounding foothills of the Schar because the town disappears when viewed together with the expansive and rich plain of Metohia. One must arrive from Djakova or Ipek. From there, one understands immediately that it is one of the most beautiful and riches towns in Turkey and one is seized with wonder by the contrast between the barren savagery of the Schar mountains and the luxuriant vegetation and vigorous population of the plain. One also understands the importance of this town which always served to hold in awe the mixture of ethnic groups in the surrounding plains and mountains. Its diverse industries and commerce on the transit route between Turkey and coastal Albania have contributed to increasing the number of its inhabitants.

The Ljevishka Church in Prizren transformed

in the Ottoman period into a mosque

(Photo: Auguste Léon, 7 May 1913).

Prizren is situated 13 postal hours from Ouskoub [Skopje], three and a half hours from Djakova, nine hours from Ipek, 11 to 11½ hours from Prischtina, and 28 or perhaps rather 30 hours from Scutari [Shkodra]. Its population surpasses 26,000 souls, for in 1838, Mr Müller counted 25,550 souls in 6,000 houses, being: 18,000 Slavs, mostly Serbs of the Greek [Orthodox] religion, and about 2,000 Zinzars [Vlachs], 2,150 Catholic Albanians, 4,000 Muslim Albanians as well as a very few real Turks and 600 Zingars [Gypsies]. The Turkish garrison is not included in these statistics and varies between 700 and 3,000 men according to whether the country is quiet or not. They have a good band of musicians. Had Mr Müller not stated clearly that his numbers derived from the haraç tax register, we would have thought the number of Slavs he gave to be exaggerated, although this would not have been typical of him.

The Catholic Church in Prizren

(Photo: Ismail Gagica).

The town is divided into three neighbourhoods: the first is to the south of the Maritza and occupies part of the hillside rising to the fortress such that some of the streets here are on a slope. This is where the konak of the pasha is situated, surrounded by high walls and consisting primarily of four wooden buildings overlooking an inner courtyard and a garden. To the west are the Turkish cemeteries and right under the fortress are the homes of the Zingars, who are mostly blacksmiths. To the northwest of this neighbourhood called Sulejmit is a neighbourhood called Eminit where almost all of the industry and commerce is to be found. The covered bazaar stretches along several long open alleys, each of which is devoted to a certain profession. We were particularly struck by the alleys of the gunsmiths and saddle-makers. The Ahmit neighbourhood, mostly to the north of the Maritza, is inhabited in good part by Christians. Here one finds not only the ruins of a church, but also the grand mosque of Ahmed which is none other than the ancient royal cathedral of Sveta Petka from the time of the Serbian Empire. One can still see beautiful large windows and on the northern side, one finds written in bricks the words Sabba srbski (Sabba the Serb). The old Serbian church of the Assumption of Our Lady has also been converted into a Friday mosque. Not far from it is the post station, the menzilhane, a large building with an upper floor of many rooms for travellers and a stable with room for more than 80 horses. It is now a very run-down hostel.

The other buildings of Prizren consist of a dozen large mosques. Mr Müller estimated their number to be 42. There is also a clock tower, a small Roman Catholic church hidden from view, and a Greek church. Prizren is the residence of the Greek bishop for northern Albania, and of a Catholic priest.

The town is not as dirty as many others in Turkey because some of the streets are on a slope and it is traversed by channels of clear flowing water. These derive mostly from the Maritza (little Mary) and bear Slavic names such as Velika, Mala and Sredna Rieka, that is, large river, small river and middle river. The drinking water is excellent. The surrounding limestone cliffs are full of it and one can see it flowing from sources on all sides.

Like the other large cities of Turkey, this one has its places of leisure, consisting mostly of cafes along the banks of the Maritza. Some of them are in the Ahmed neighbourhood on the northern bank of the Maritza not far from a wooden bridge and the Serbian cathedral. Lofty poplars, alders and plane trees shade and protect the town from the rays of the sun such that one can walk along the sandy banks. The other cafes are situated at the entrance to the gorge of the Schar out of which the Maritza flows. Some Oriental planes offer protection from the sun and are as agreeable as the swift flowing water which refreshes the air with its vapors. It is a delight here to observe the cliffs under the fortress.

Going up the twisty gorge of the Maritza, one comes to the ruins of a small monastery at one hour from Prizren. Here the Serbs or Slavs used to come on pilgrimages. Could this be the monastery of the Archangel Michael, where Tsar Dushan was buried? According to the monk Jurišić, somewhere in the mountains half an hour from Prizren there are three Greek churches, being those of the Ascension, of Saint George the Martyr and of the Archangel (Arandjel). On top of a high cliff are the ruins of a fortress. If one proceeds further, one gradually climbs up along limestone promontories which serve as a path to reach the high slopes of Ljoubeten from where one can descend to Katschanik. These overlook the plain of Kosovo and a good part of upper Moesia, which is bordered by mountain chains to the north and south. We took this road, or rather trail, in 1837. At that time it was well-travelled with a crowd of merry Albanians returning to their villages. These were men that the pasha had armed and given European dress. They were a type of national guard, or Redif, which came down to Prizren from time to time to exercise. They were mostly young men and they took great pleasure in allowing me to inspect their weapons. The heights are inhabited by a robust mixture of Albanians and Serbs, with the villages generally hidden in the gorges.

[extracts from Ami Boué, Recueil d’itinéraires dans la Turquie d’Europe. détails géographiques, topographiques et statistiques sur cet empire (Vienna: W. Braumüller, 1854), p. 192-208, 346-352 and 315-318. Translated from the French by Robert Elsie.]

TOP