| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

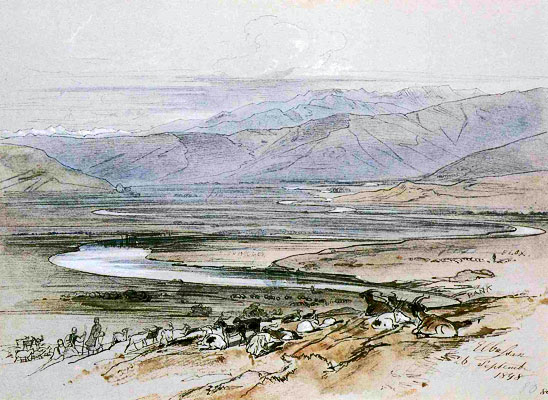

Paintings Edward Lear,

"Elbasan, 26 Sept. 1848".

![]()

Paintings Edward Lear,

"Tirana, 28 Sept. 1848".

1848

Edward Lear:

The Devil Writes

The English poet and painter Edward Lear (1812-1888) was born in Highgate (London), the twentieth of twenty-one children. He was a passionate painter from an early age and received a commission from the Earl of Derby to paint landscapes in the Mediterranean. He travelled to Albania in the autumn of 1848 on an originally unplanned journey. It was the British ambassador in Constantinople who managed to get the requisite papers for him to travel through what was then considered the wilds of the Ottoman Empire. Starting from Thessalonika, he arrived in Monastir (Bitola) on 20 September, accompanied by his temperamental dragoman Giorgio. From there, they continued on to Ohrid, Struga, Elbasan, Tirana, Kruja, Lezha and Shkodra, which they reached on 2 October. After several days there, they returned to Tirana and continued southwards to Kavaja, Berat (14-18 October), Ardenica, Apollonia, Vlora, the coast of Himara (21-30 October), Tepelena, Gjirokastra and on to Janina (5 November). The delightful account of the journey, of which we provide an excerpt here, was published in his "Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania," London 1851, reprinted as “Edward Lear in Albania: Journals of a Landscape Painter in the Balkans.” Edited by Bejtullah Destani and Robert Elsie (I.B. Tauris, in association with the Centre for Albanian Studies, London 2008). Many of the landscape paintings and sketches he made during the journey provide an accurate topographical record of mid-nineteenth century Albania.

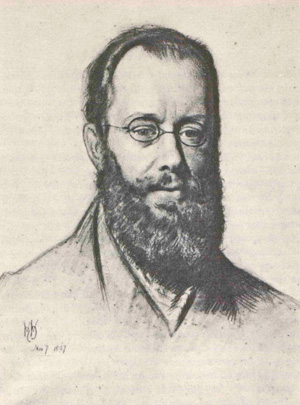

Edward Lear

drawn by Holman Hunt

SEPTEMBER 26th, 1848

A grey, calm, pleasant morning. The air seeming doubly warm from the contrast between the low plains and the high mountains of the last two days' journey. I set off early to make the most of a whole day at Elbassán - a town singularly picturesque, both in itself, and as to its site. A high and massive wall with a deep outer moat surrounds a large quadrangle of dilapidated houses, and at the four corners are towers, as well as two at each of the four gates: all of these fortifications appear of Venetian structure. Few places can offer a greater picture of desolation than Elbassán, albeit the views from the broad ramparts extending round the town are perfectly exquisite: weeds, brambles, and luxuriant wild fig overrun and cluster about the grey heaps of ruin, and whichever way you turn, you have a middle distance of mosques and foliage, with a background of purple hills, or southward, the remarkable mountain of Tomóhr, the giant Soracte of the plains of Berát.

No sooner had I settled to draw - forgetful of Bekir the guard - than forth came the populace of Elbassán, one by one, and two by two, to a mighty host they grew, and there were soon from eighty to a hundred spectators collected, with earnest curiosity in every look; and when I had sketched such of the principal buildings as they could recognise, a universal shout of "Shaitán!" (Devil!) burst from the crowd, and strange to relate, the greater part of the mob put their fingers into their mouths and whistled furiously, after the manner of butcher-boys in England.

Whether this was a sort of spell against my magic I do not know, but the absurdity of sitting still on a rampart to make a drawing, while a great crowd of people whistled at me with all their might, struck me so forcibly, that come what might of it, I could not resist going off into convulsions of laughter, an impulse the Ghéghes seemed to sympathise with, as one and all shrieked with delight, and the ramparts resounded with hilarious merriment. Alas! this was of no long duration, for one of those tiresome Dervishes - in whom, with their green turbans, Elbassán is rich - soon came up, and yelled, "Shaitán scroo! Shaitán!" (The Devil writes! Devil!) in my ears with all his force, seizing my book also, with an awful frown, shutting it, and pointing to the sky, as intimating that heaven would not allow such impiety. It was in vain after this to attempt more; the "Shaitán" cry was raised in one wild chorus - and I took the consequences of having laid by my fez for comfort's sake - in the shape of a horrible shower of stones, which pursued me to the covered streets, where, finding Bekir with his whip, I went to work again more successfully about the walls of the old city. Knots of the Elbassaniotes nevertheless gathered about Bekir, and pointed with angry gestures to me and my 'scroo.' "We will not be written down," said they. "The Frank is a Russian, and he is sent by the Sultan to write us all down before he sells us to the Russian Emperor." This they told also to Giorgio, and murmured bitterly at their fate, though the inexorable Bekir told them they should not only be scroo'd, but bastinadoed, if they were not silent and obedient. Alas! it is not a wonder that Elbassán is no cheerful spot, nor that the inhabitants are gloomy. Within the last two years one of the most serious rebellions has broken out in Albania, and has been sternly put down by the Porte. Under an adventurer named Zuliki, this restless people rose in great numbers throughout the north-western districts; but they were defeated in an engagement with the late Seraskier Pashá. Their Beys, innocent or accomplices, were exiled to Koniah or Monastir, the population was either drafted off into the Sultan's armies, slain, or condemned to the galleys at Constantinople, while the remaining miserables were and are more heavily taxed than before. Such, at least, is the general account of the present state of these provinces; and certainly their appearance speaks of ill-fortune, whether merited or unmerited. Beautiful as is the melancholy Elbassán - with its exquisite bits of mosques close to the walls - the air is most oppressive, after the pure mountain atmosphere. How strange are the dark covered streets with their old mat roofing hanging down in tattered shreds, dry leaves, long boughs, straw or thatch reeds; one phosphorus match would ignite the whole town! Each street is allotted to a separate bazaar, or particular trade, and that portion which is the dwelling of the tanners and butchers is rather revolting, - dogs, blood, and carcasses filling up the whole street, and sickening one's very heart.

At three P.M. I rode out with the scarlet and gold-clad Bekir to find a general view of the town. But the long walled suburbs, and endless olive-gardens, are most tiresome, and nothing of Elbassán is seen till one reaches the Skumbi, spanned by an immensely long bridge, full of ups and downs and irregular arches. On a little brow beyond the river I drew till nearly sunset; for the exquisitely graceful lines of hill to the north present really a delightful scene, - the broad, many-channelled stream washing interminable slopes of rich olives, from the midst of which peep the silver minarets of Elbassán.

The dark khan cell at tea-time was enlivened by the singing of some Gheghes in the street. These northern, or Sclavonic Albanians are greatly superior in musical taste to their Berát or Epirote neighbours, all of whom either make a feeble buzzing or humming over their tinkling guitars, like dejected flies in a window-pane, or yell forth endless stanzas of a whining, monotonous song, somewhat resembling a bad imitation of Swiss yodelling. But here there is a better idea of music. The guardian Bekir indulged me throughout yesterday with divers airs, little varied, but possessing considerable charm of plaintive wild melody. The Soorudji, also, made the passes of the Skumbi resound with more than one pretty song.

SEPTEMBER 27th, 1848

Great was my alarm, when two hours before sunrise the whole khan was knocked up by a government Tatar, raging for horses to proceed towards Skódra. All that were to be found in Elbassán I had engaged for my own journey, and the fear was, that should the Khanji yield our steeds to the new-comer, my detention in so charming a place as this might be indefinitely prolonged; but for some reason of his own the Khanji chose to lie in the most fertile manner, saying that some of his horses were ill, some away; and so the baffled Tatar retreated; and as the fibs were not uttered by my orders I became composed, and went to sleep again with a good conscience.

At half-past six A.M. we left Elbassán, Giorgio growling at all the inhabitants, and wishing they might be sold to the Czar, according to their fears. In any case, attachment to Abdul Medjid is not the reigning characteristic of this forlorn place. It was long before we left walls and lanes (there is more cultivation, especially of the olive, in these environs than in any part of Albania I have yet seen), or ceased to jostle in narrow places against mules laden with black wool, and driven by white-garbed, black-cloaked men, but when the route began to ascend from the valley, the view southward over to Skumbi, in which the giant Tomóhr, forms the one point of the scene, was remarkably grand. In the early morning's ride there was but little interest; the greater part of it being through the narrow valley of a stream tributary to the Skumbi; the winding bed of which torrent we crossed more than thirty times ere we left it; and much after-time was occupied in painfully coasting bare clay hills till we began to climb the sides of the high mountain which separates the territory of Elbassán from that of Tyrana.

How glorious, in spite of the dimming sirocco haze, was the view from the summit, as my eyes wandered over the perspective of winding valley and stream to the farthest edge of the horizon - a scene realizing the fondest fancies of artist imagination! The wide branching oak, firmly rivetted in crevices, all tangled over with fern and creepers, hung half-way down the precipices of the giant crag, while silver-white goats (which chime so picturesquely in with such landscapes as this) stood motionless as statues on the highest pinnacle, sharply defined against the clear blue sky. Here and there the broken foreground of rocks piled on rocks, was enlivened by some Albanians who toiled upwards, now shadowed by spreading beeches, now glittering in the bright sun on slopes of the greenest lawn, studded over with tufted trees, which recalled Stothard's graceful forms, so knit with my earliest ideas of landscape. These and countless well-loved passages of auld lang syne, crowded back on my memory as I rested, while the steeds and attendants reposed under the cool plane tree shade, and drank from the sparkling stream which bubbled from a stone fountain. It was difficult to turn away from this magnificent mountain view - from these chosen nooks and corners of a beautiful world - from sights of which no painter-soul can ever weary: even now, that fold beyond fold of wood, swelling far as the eye can reach - that vale ever parted by its serpentine river - that calm blue plain, with Tomóhr in the midst, like an azure island in a boundless sea, haunt my mind's eye, and vary the present with visions of the past. With regret I turned northwards to descend to the new district of Tyrana; the town (and it is now past eleven) being still some hours distant.

By half-past twelve we had descended into a broad undulating valley-plain, with limits melting into undistinguishable hill and sky (for the day was a sirocco with its dust-like mist, and the atmosphere like an oven), and were, soon at a roadside khan, where a raised platform, with matting shelter, was by no means unacceptable. The magnificent Akhridhan, Bekir, who was charged to accompany me as far as Tyrana, is of very little service in any way; his first care is to secure a good place on the platform - to take off his shoes, and smoke; while Giorgio's alacrity in cooking a good dinner is a strong contrast to the Albanian's idleness. There were whispering olives hanging over the khan-yard; and while a simple melody was chanted by three Ghéghes in the shade, the warm, slumbrous midday halt brought back to memory many such scenes and siestas in Italy.

Starting at two, the scenery along the banks of a river, a noble stream enclosed between fine rocks (the name of which I know not) was fine and varied; but the fear of arriving late at Tyrana urged me onward, to the omission of all drawing - though, had time allowed, it would not have been easy to have selected only one from so many continually-changing pictures as the afternoon's ride afforded. Other things also, good and bad, were included in the day's carte, such as capital grapes at the khan, and from frequent gardens as we approached Tyrana; - many objects of costume among the peasantry, - great flocks of turkeys, - and insecure wooden bridges over little streams, which obliged us, for fear of the horses falling through the planks, to make detours through charming bosky oases of cultivation. At four we forded the river, and hastened on, gradually descending by low brushwood undulations to the plain of Tyrana, while to the east, the long rugged range of the Króia mountains became magnificently interesting from picturesqueness and historical associations.

A snake crossing the road gave Giorgio an occasion, as is his afternoon's wont, to illustrate the fact with a story. "In Egitto," said he, "are lots of serpents; and once there were many Hebrews there. These Hebrews wished to become Christians, but the King Pharaoh - of whom you may have heard - would not allow any such thing. On which Moses (who was the prince of the Jews) wrote to the Patriarch of Constantinople and to the Archbishop of Jerusalem, and also to San Carlo Borromeo, all three of whom went straight to King Pharaoh, and entreated him to do them this favour; to which he only replied 'No, signori.' But one fine morning these three saints proved too strong for the King, and changed him and all his people into snakes; which," said the learned dragoman, "is the real reason why there are so many serpents in Egypt to this day."

Wavy lines of olive - dark clumps of plane, and spirally cypresses marked the place of Tyrana when the valley had fully expanded into a pianura, and the usual supply of white minarets lit up the beautiful tract of foliage with the wonted deceptive fascination of these towns. As I advanced to the suburbs, I observed two or three mosques most highly ornamented, and from a brilliancy of colour and elegance of form, by far the most attractive of any public building I had yet beheld in these wild places; but though it was getting dark when I entered the town (whose streets, broader than those of Elbassán, were only raftered and matted half way across), it was at once easy to perceive that Tyrana was as wretched and disgusting as its fellow city, save only that it excelled in religious architecture and spacious market places.

Two khans, each abominable, did we try. No person would undertake to guide us to the palace of the Bey (at some distance from the town), nor at that hour would it have been to much purpose to have gone there. The sky was lowering; the crowds of gazers increasing - Albanian the only tongue; so, all these things considered, I finally fixed on a third-rate khan, reported to be the 'Clarendon' of Tyrana, and certainly better than the other two, though its horrors are not easy to describe nor imagine. Horrors I had made up my mind to bear in Albania, and here, truly, they were in earnest.

Is it necessary, says the reader, so to suffer? and when you had a Sultan's Boyourldi could you not have commanded Beys' houses? True; but had I done so, numberless arrangements become part of that mode of life, which, desirous as I was of sketching as much as possible, would have rendered the whole motives of my journey of no avail. If you lodge with Beys or Pashás, you must eat with them at hours incompatible with artistic pursuits, and you must lose much time in ceremony. Were you so magnificent as to claim a home in the name of the Sultan, they must needs prevent your stirring without a suitable retinue, nor could you in propriety prevent such attention; thus, travelling in Albania has, to a landscape painter, two alternatives; luxury and inconvenience on the one hand, liberty, hard living, and filth on the other; and of these two I chose the latter, as the most professionally useful, though not the most agreeable.

O the khan of Tyrana! with its immense stables full of uproarious horses; its broken ladders, by which one climbed distrustfully up to the most uneven and dirtiest of corridors, in which a loft some twenty feet square by six in height was the best I could pick out as a home for the night. Its walls, falling in masses of mud from its osier-woven sides (leaving great holes exposed to your neighbour's view, or, worse still, to the cold night air); - its thinly raftered roof, anything but proof to the cadent amenities resulting from the location of an Albanian family above it; its floor of shaking boards, so disunited that it seemed unsafe to move incautiously across it, and through the great chasms of which the horses below were open to contemplation, while the suffocating atmosphere produced thence are not to be described!

O khan of Tyrana! when the Gheghe Khanji strode across the most rotten of garrets, how certainly did each step seem to foretell the downfall of the entire building; and when he whirled great bits of lighted pitch-torch hither and thither, how did the whole horrid tenement seem about to flare up suddenly and irretrievably!

O khan of Tyrana! rats, mice, cockroaches, and all lesser vermin were there. Huge flimsy cobwebs, hanging in festoons above my head; big frizzly moths, bustling into my eyes and face, for the holes representing windows I could close but imperfectly with sacks and baggage: yet here I prepared to sleep, thankful that a clean mat was a partial preventive to some of this list of woes, and finding some consolation in the low crooning singing of the Gheghes above me, who, with that capacity for melody which those Northern Albanians seem to possess so essentially, were murmuring their wild airs in choral harmony.

SEPTEMBER 28th, 1848

Though the night's home was so rude, fatigue produced sound sleep. The first thing to do was to visit Machmoud Bey, vice-governor of Tyrana, to procure a Kawás as guardian during a day's drawing, and a letter to his nephew, Alí Bey, of Króia, for to that city of Scanderbeg I am bent on going. Of the Bey's palace, nothing can be said beyond what has already been noted of the serais of similar grandees.

Returning to the khan, I gave five dollars to Bekir of Akhridha, for his five days' service, an expense I resolved in future to forego, as the chance of robbery in these mountains seems a great deal too small to authorize it - the more, that the only assistance I really want (that of a guard while sketching in the towns) I have no difficulty in procuring. But even with a guard, it was a work of trouble to sketch in Tyrana; for it was market, or bazaar day, and when I was tempted to open my book in the large space before the two principal mosques - (one wild scene of confusion, in which oxen, buffaloes, sheep, goats, geese, asses, dogs, and children, were all running about in disorder) - a great part of the natives, impelled by curiosity, pressed closely to watch my operations, in spite of the Kawás, who kept as clear a space as he could for me; the women alone, in dark feringhis, and ghostly white muslin masks, sitting unmoved by their wares. Fain would I have drawn the exquisitely pretty arabesque-covered mosques, but the crowds at last stifled my enthusiasm. Not the least annoyance was that given me by the persevering attentions of a mad or fanatic dervish, of most singular appearance as well as conduct. His note of "Shaitán" was frequently sounded; and as he twirled about, and performed many curious antics, he frequently advanced to me, shaking a long hooked stick, covered with jingling ornaments, in my very face, pointing to the Kawás with menacing looks, as though he would say, "Were it not for this protector you should be annihilated, you infidel!" The crowd looked on with awe at the holy man's proceedings, for Tyrana is evidently a place of great attention to religion.

In no part of Albania are there such beautiful mosques, and nowhere are collected so many green-vested dervishes. But however a wandering artist may fret at the impossibility of comfortably exercising his vocation, he ought not to complain of the effects of a curiosity which is but natural, or even of some irritation at the open display of arts which, to their untutored apprehension, must seem at the very least diabolical.

The immediate neighbourhood of Tyrana is delightful. Once outside the town and you enjoy the most charming scenes of quiet, among splendid planes, and the clearest of streams. The afternoon was fully occupied in drawing on the road from Elbassan, whence the view of the town is beautiful. The long line of peasants returning to their homes from the bazaar, enabled me to sketch many of their dresses in passing; most of the women wore snuff-coloured or dark vests trimmed with pink or red, their petticoats white, with an embroidered apron of chocolate or scarlet; others affected white capotes; but all bore their husband's or male relative's heavy black or purple capote, bordered with broad pink or orange, across their shoulders. Of those whose faces were visible - for a great part wore muslin wrappers - (no sign hereabouts of the wearer being Mohammedan, for both Moslem and Christian females are thus bewrapped) - -some few were very pretty, but the greater number had toil and careworn faces. There were many dervishes, also, wearing high, white felt, steeple-crowned hats, with black shawls round them.

No sooner, after retiring to my pig-stye dormitory, had I put out my candle and was preparing to sleep, than the sound of a key turning in the lock of the next door to that of my garret disturbed me, and lo! broad rays of light illumined my detestable lodging from a large hole a foot in diameter, besides from two or three others just above my bed; at the same time a whirring, humming sound, followed by strange whizzings and mumblings began to pervade the apartment. Desirous to know what was going on, I crawled to the smallest chink, without encountering the rays from the great hiatus, and what did I see? My friend of the morning - the maniac dervish - performing the most wonderful evolutions and gyrations; spinning round and round for his own private diversion, first on his legs, and then pivot-wise, "sur son seant," and indulging in numerous other pious gymnastic feats. Not quite easy at my vicinity to this very eccentric neighbour, and half anticipating a twitch from his brass-hooked stick, I sat watching the event, whatever it might be. It was simple. The old creature pulled forth some grapes and ate them, after which he gradually relaxed in his twirlings, and finally fell asleep.

SEPTEMBER 29th, 1848

It was as late as half-past nine A.M. when I left Tyrana, and one consolation there was in quitting its horrible khan, that travel all the world over, a worse could not be met with. Various delays prevented an early start; the postmaster was in the bath, and until he came out no horses could be procured (meanwhile I contrived to finish my arabesque mosques); then a dispute with the Khanji, who, like many of these provincial people, insisted on counting the Spanish dollar as twenty-three, instead of twenty-four Turkish piastres. Next followed a row with Bekir of Akhridha, who vowed he would be paid and indemnified for the loss of an imaginary amber pipe, which he declared he had lost in a fabulous ditch, while holding my horse at Elbassan; and lastly, and not the least of the list, the crowd around the khan gave way at the sound of terrific shrieks and howlings, and forth rushed my spinning neighbour, the mad dervish, in the most foaming state of indignation. First he seized the bridles of the horses; then, by a frantic and sudden impulse, he began to prance and circulate in the most amazing manner, leaping, and bounding, and shouting "Allah!" with all his might, to the sound of a number of little bells, which this morning adorned his brass-hooked weapon. After this he made an harangue for ten minutes, of the most energetic character, myself evidently the subject; at the end of it he advanced towards me with furious gestures, and bringing his hook to within two or three inches of my face, remained stationary, in a Taglioni attitude. Knowing the danger of interfering with these privileged fanatics, I thought my only and best plan was to remain unmoved, which I did, fixing my eye steadily on the ancient buffoon, but neither stirring nor uttering a word; whereon, after he had screamed and foamed at me for some minutes, the demon of anger seemed to leave him at a moment's warning; for yelling forth discordant cries, and brandishing his stick and bells, away he ran, as if he were really possessed. Wild and savage were the looks of many of my friend's excited audience, their long matted, black hair, and brown visage, giving them an air of ferocity, which existed perhaps more in the outward, than the inner man; moreover, these Gheghes are all armed, whereas out of Ghegheria no Albanian is allowed to carry so much as a knife.

I was glad enough to leave Tyrana, and rejoiced; in the broad green paths, or roads, that lead northwards, through a wide valley below the eastern range of magnificent mountains, on one of which, at a great height from the plain, stands the once formidable Kroia, so long held out against the conquering Turk, by Iskander Bey. Certain of its historical interest, I was now doubly anxious to visit it, from its situation, which promised abundance of beauty.

[Taken from Edward Lear: Journals of a Landscape Painter in Albania (London 1851).]

TOP