| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

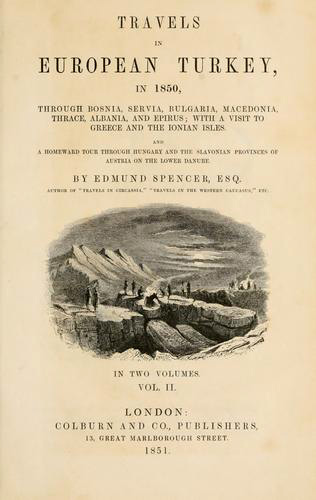

Title page of "Travels in European Turkey", 1850.

1850

Edmund Spencer:

A Journey from Ohrid to Janina

Captain Edmund Spencer was a prolific British travel writer of the mid-nineteenth century. He seems to have lived in Prussia for a time. His first travel book was entitled “Sketches of Germany and the Germans, with a glance at Poland, Hungary, & Switzerland in 1834, 1835, and 1836, by an English resident of Germany” (London 1836). He was in contact with German travel writer, Count Hermann Pückler-Muskau (1785-1871), whose book “Tutti Frutti” he translated into English (London 1836). Spencer’s second great tour took him down the Danube from Vienna to Constantinople and the Black Sea where he visited the Caucasus. He hereafter published his “Travels in the Western Caucasus” (London 1838) and other volumes on the region. Finally, in 1850, Spencer undertook an extensive voyage through the southern Balkans, which he described in his two-volume “Travels in European Turkey, in 1850, through Bosnia, Servia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Thrace, Albania, and Epirus, with a visit to Greece and the Ionian Isles” (London 1851). The Albanian portion of this epic journey took him on horseback and on foot from Ohrid to Mirdita, Elbasan, Kruja, Shkodra and up to Kotor, and then back to Elbasan from where he continued on to Berat, Përmet, and Janina. This description of mid-nineteenth century Albania, with much rare insight, is given as follows.

A Journey from Ohrid to Janina

CHAPTER IVImperial fisheries of the Sultan – Defile of the Drin – Ascent of the Miriditi Mountains – Hospitality of the inhabitants – Aspect of the country – Arrival at the Djeta of a Miriditi chieftain – Sketch of Hamsa, the chief – His singular history – Austrian and Italian missionaries – Fanaticism of the Miriditi – Stefa, my kiraidji – Some account of him – The versatility of his religious opinions – The pass of Keupris – Dangerous travelling – Rencontre with a part of Albanian rebels – Ancient bridge over the Scoumbi – Arrival at Elbassan – Description of the town and its inhabitants – The Albanian tribes – Their political tendencies – Some account of the independent tribes of the Miriditi – Depopulation of Albania.

For want of space, we are compelled to conclude our sketches of Ocrida [Ohrid] and its beautiful lake, which if Monsieur Voltaire had seen, he never would have said, when writing upon Geneva, “Mon lac est le premier lac du monde!” And now, having secured another kiraidji, accompanied by my friend, the Missionary from Vienna, we set out for the mountain home of the those independent tribes of Albanian, the Miriditi [Mirdita], the worthy priest assuring me that we should not only meet with a hospitable reception from his co-religionists, but find a chief there who spoke the English language fluently.

On leaving Ocrida, our route lay along the banks of the lake, over meadows like a bowling-green, till we came to the little town of Strouga [Struga], distant about two leagues; here, in compliance with a previous invitation, we passed the remainder of the day and night at the house of a very worthy man, Demetrius Miladin, who had been to Italy and Trieste, and spoke the Italian language fluently. Our short stay here afforded us an opportunity of visiting the imperial fisheries, and however clumsily erected, they yielded the Sultan an annual revenue of a hundred thousand piastres. Here we also plied our fishing-rod, and succeeded even better in charming the trout than in the Lake of Ocrida; they are smaller in size but far more numerous.

After passing the bridge at Strouga, we followed the banks of the Tzerna Drina (Black Drina), to distinguish it from the White Drin, which, rising in the Alpine district of the Scardus, in Upper Albania, meets the Black Drin at Stana, and forms one river. About a league, or a league and a half from Strouga, the defile of the Drin commences, so famous during the wars of the Turks and the Christians in the time of Scanderbeg, and said to be the most formidable and dangerous to the advance of an enemy of any in European Turkey; and truly the wild aspect of the landscape before us – the river dashing through its narrow bed, enclosed within piles of rocks shooting up till their summits are lost in the clouds, rendered still more sombre by the dark foliage of trees springing out of every fissure, might suffice to appal the stoutest heart in a position that offered no security from the attack of an enemy in possession of the heights, who had only to hurl down the loose fragments of rocks to crush every living thing beneath them; and this is the only entrance from the vast basin of Ocrida into the mountain retreat inhabited by those independent tribes of Albania called the Miriditi.

We passed through a couple of villages inhabited by the Mahometan Miriditi, who to distinguish themselves from their Christian brethren occupying the higher regions of the mountain, call themselves the Djeghi [Gheg]. We will say nothing about their religious feelings, but I thought there was more respect displayed towards my companion, the missionary, who appeared to be no stranger to them, than was consistent with the usual bearing of good Mahometans.

The Black Drin Valley near Peshkopia

(Photo: Robert Elsie, December 2008).On leaving the defile of the Drin, so aptly named by the Turks the Kara-Drina, we ascended, or rather climbed up, the steep sides of the mountain through a cleft in the rocks, in rainy weather the bed of a cataract, where it required all our care to steady the feet of our trembling steeds. At length we got to the summer of a beautiful plateau, with a neat village surrounded by cultivated fields, and flocks of sheep and goats browsing on the surrounding slopes; the small white chapels with Latin crosses, sufficiently indicated that we were now within what may be called the territory of the Latin Miriditi. Here we remained for the night, the hospitable mountaineers providing every necessary that could conduce to our comfort.

On continuing our route through this secluded mountain region, I was agreeably surprised to see a succession of these little hamlets with their orchards and fields, in which maize and barley appeared the principal productions; indeed, every spot capable of culture was tilled with the most indefatigable industry and every rivulet artificially turned and divided into a succession of tiny streamlets for the purpose of irrigation. In a few favoured situations they grew a little tobacco for their own use; and here and there in a field or two, supported by terraces constructed of fragments of the rock, the vine and the walnut were growing in the richest luxuriance; still the great source of wealth to these mountaineers consists in their flocks of sheep and goats, together with the produce of the apiary. Forests of the noble oak also are seen occasionally feathering the sides of the mountain, but in a country without roads or navigable rivers, they yield no profit whatever to the inhabitants, except what they convert to their own use.

From time to time we found the mountains broken and split into narrow, deep gorges, as if by an earthquake, between which there was no connexion but a species of bridge constructed of trunks of trees, disclosing a yawning abyss beneath frightful to behold. To cross one of these, without any railing or support required no little nerve; yet if we could divest ourselves of the fear, so natural to man, knowing that the slightest false step hurls him to destruction, there is in reality no more danger to be apprehended, than if they were thrown over a rivulet a few feet in depth. With man, habit is second nature; but we did not find it so with our horses. Our greatest difficulty was in getting them over with their unwieldy pack-saddles, not always securely fastened or properly balanced; and notwithstanding all their good qualities and sure-footedness in mountain travelling, and some portion of courage, not one of them would cross these bridges without being blindfolded, with a man at the head of each horse, and another to steady the saddle; and then the moment their feet touched the wooden plank they trembled so violently, that it required all the endearing epithets of the kiraidji to comfort them during the passage, lest they should actually from fear and weakness tumble down the precipice. Sometimes when we gained the summit of one of these mountains, and the horizon opened to the vision, we saw around us a boundless labyrinth of gorges and deep defiles intersecting each other, overcapped by a chaos of rocks, torn, broken and split, with here and there a naked peak still streaked with snow, running up to a height of between five and six thousand feet. How great must be the love of freedom inherent in man when he has sought such a country as this for his habitation!

At length we arrived at a small but beautiful plateau, in the centre of which lay a village, a little Eden, surrounded by orchards, corn-fields and meadows, through which was roaring a torrent on its way to swell the waters of the Scoumbi [Shkumbin]. This was the Djeta, or principal resident of the chieftain and his clansmen. It was evident from the reception we met with, the discharge of fire-arms, and the number of kilted warriors who came to welcome us, that my friend, the missionary, had heralded our visit by an avant courier. We were at once conducted to the koula of the chief, a stone building surmounted by a species of fortified tower, sufficiently strong to resist a discharge of musketry, with port-holes and a gallery surrounding it. We found the entire household engaged in cooking in the open air around several large fires. In one place a whole sheep roasting on a wooden spit, gave evidence that the principal men of the tribe had been invited to enjoy the feast.

Hamsa, the chief, who looked the very personification of a mountain warrior, although past the meridian of life, was still a splendid fellow. In early youth he had the misfortune to kill the son of a neighbouring chief during one of their oft-recurring faidas (domestic quarrels); this obliged him to seek safety in flight, as these people still regard vengeance for blood that is shed as one of the first laws of nature, and in this neither the humanizing precepts of the faith they profess, nor the exhortations of their clergy, have been able to effect a reformation. In vain he sought an asylum among the Austrians at Cattaro; revenge tracked him thither; and his life would have paid the penalty, had he not crossed the sea to Corfu. Here, having changed his name, and by some employment or commerce contrived to amass a little fortune, he was enabled to pay such a fine as satisfied the relatives of the deceased, and permitted him to return with safety and independence to his tribe. He spoke a mixture of the English and Italian languages intelligible to me. This was fortunate, as I did not understand the Albanian, except such words as were derived from the Turkish, Slavonian or Latin. He mentioned the name of Sir Thomas Maitland and of several other distinguished officers quartered there during his exile; and he must have been well treated, for he lauded the character of the English to the seventh heaven; a people he said the most generous and highly-gifted, who knew everything, and did everything better than any other; concluding his eulogium, by hoping the day was not far distant when he might hail them as the rulers of Albania!

Hamsa’s admiration for the English did not evaporate in empty declamation. During his sojourn in the land of the stranger he had learned much, the beneficial effects of which were visible, so far as the influence of his example and means extended. The huts of his clansmen were neater, and their gardens and fields better cultivated, than those of their neighbours; he had built a little church, and endowed a school with land, where the youths of his clan received an education suitable at least to their mode of life. Having lost his wife, and being without children, he devoted his time and energies to the services of his clansmen; still he regretted the loss of those delights of a more civilized existence he had previously enjoyed, but the love he bore to his tribe and his native mountains, prevailed over every other consideration.

The fra missionary who was accustomed to visit Hamsa’s tribe, was evidently a great favourite; he knew everybody, and was regarded by young and old as a saint. He had brought with him a large collection of little wooden crucifixes, painted engravings of Madonnas, saints and angels; these he distributed most liberally, accompanied by his benediction, among the people, who received them with acclamations of delight and admiration: they had now in their possession a talisman, which must triumph over the Evil One, and bring prosperity and happiness to their homes. “It is well,” said Hamsa, turning to me with a grave countenance, “you English have been better taught; but these poor, simple people would require a century before they could be brought to appreciate the excellence of the form of worship I have seen practised in your church at Corfu. Again, their eternal feuds, and their division into so many opposing creeds – Latin, Greek and Mahometan – each hating the other with all the bitterness of religious fanaticism, has been the cause of all our evils: were it not for this, we should long since have driven forth the Osmanli, with their debasing harritch; and Albania, with its mountains, rich plains, valleys and sea, would have been independent.”

“Although,” continued the patriot, “we are Miriditi of the pure race of Scanderbeg, and enjoy here, thanks to the fastness of our native mountains, and the bravery of our people, a species of freedom; yet our isolation from all commerce with our brethren of the lowlands, perpetuates our ignorance and fanatic hatred of every other people and creed differing from ours, and exposes us alike to the hostility of the Mahometans, and the Slavonian and Hellenic Greeks. I did once entertain the hope,” added Hamsa, “while I remained an exile among your people, of forming a union with our brethren of the lowlands, the Djeghi, of whatever religious persuasion. The attempt was made and failed: Osmanli gold prevailed, our leader, Moustapha, Pacha of Scutari, proved a traitor, and I have had to deplore the loss of my only boy. The Osmanli, however, have been again taught to respect our bravery, and a better feeling has sprung up between the tribes of our race, the Miriditi, of whatever religious persuasion.

It were to be wished that these fanatic Romanists, the Miriditi mountaineers, had a few more men among them, possessing the same enlightened views as their countryman, Hamsa. I was much pleased in having met with him, and regretted that I could not accept his invitation, and prolong my stay at his koula, and become more intimate with the manners and customs of these interesting mountaineers. According to every information we received, the insurrection of the Musulman inhabitants of Albania was increasing, which determined me without loss of time to proceed towards the sea-coast, and leave the country, if circumstances should so dictate. Here I also parted from my friend, the missionary, and again set forth on my journey.

I was this time accompanied by a native of Macedonia, as a kiraidji; he was an excellent fellow in his way, spoke a little Italian, which, with his own patois, a mixture of Albanian, Slavonian, Greek, and Turkish, enabled us to understand each other. Among his other qualifications, as a kiraidji, he was lively and communicative, knew the country well, and the character of the inhabitants, and how to avoid danger while travelling through a land in so disorganised a state as Albania; he was also full of anecdote, whether real or imaginary, and among other things amused me with accounts of the great antiquity of his own family, for Stefa was nothing less than a descendant of the Macedonian Kings!

On leaving the village, Hamsa, and half a dozen of his warriors, accompanied us on our route, a precaution absolutely necessary among a people so suspicious of strangers; and, perhaps, there is no part of European Turkey, in which the traveller incurs so much danger as in this mountain district. If he travels in the costume of an Osmanli, he runs a fair chance of being shot by the first half-wild Skipetar he meets with. The heretical Greek is equally detested; but as he is considered a religious, not a political enemy, if he enters the country he is left to die of starvation, for not a single individual among these fanatic Romanists would defile himself or his house, by giving food or shelter to a man excommunicated by the Holy Latin Church, and only fit to herd with brutes. From these dangers and difficulties the Frank traveller is safe so long as he remains among the Miriditi, who believe the Christian world to consist only of Romanists and schismatic Greeks; he must, however, be accompanied by a Miriditi, to certify that he is not a spy. Again the Frank traveller, who journeys through the country, has another advantage, since he is certain to meet with some Italian or German missionary, not very learned in theology, but pleasant companions, who enjoy most heartily a good supper, and a bottle of wine, and listen with delight to the latest news of the great world they have left.

Hamsa, although nearly seventy years of age, sat on his horse with all the firmness of a youthful warrior; for these people continue to the close of life to be strangers to the decrepitude that is certain to overtake the man who lives in the enjoyment of luxury. The costume of the old chief and indeed that of the inhabitants of these mountains of either sex, was similar to that of those tribes of the same race, we already described while travelling at Ipek [Peja] and Prizren, on the other side of the mountains of Upper Albania; the many-plaited phistan, made of white calico, had a singular and not unpicturesque effect, when they were on horseback, and contrasted well with the crimson vest, red fez, and long Arnout gun.

My kiraidji, Stefa, also wore the phistan and red fez, but his braided jacket, which he usually hung over his shoulder like that of a hussar, was dingy white and made of coarse wool. His creed appeared to be that of the Vicar of Bray, at all events, I never could make it out satisfactorily; among the Miriditi mountaineers he was a Romanist, and denounced the schismatic Greeks as the dogs of all dogs, the greatest sinners in the universe. On the plain where the majority of the population professed the Greek religion, his chameleon faith assumed a different character; now he abhorred the carved image worshipping of the Latin wolves, the Miriditi, who were all idolators, and damned to all eternity. When he mingled with the Children of the Crescent, he complied with their customs, and imitated their religious observances; and being a good singer, never failed to conciliate their friendship by singing some song that flattered their self-love and national pride, whether Osmanli or Albanian.

With all the quickness and sharp intellect of the Greek, Stefa combined the honesty of the Slavonian, but he was one of the ugliest men I ever saw, the greatest talker, the most slavish flatterer and coward in existence; these little foibles, however, did not retard his worldly success, for he was considered to be very wealthy by his townspeople at Strouga. In his capacity of pedlar, he was accustomed to traverse these provinces in every direction, knew every person and every place; and the inhabitants of the different towns and villages looked forward to a visit from Stefa as a most desirable event, since he supplied the men, who universally shave their head, with cotton skull caps, braiding for the jackets, and bright gilt clasps, buttons, and sundry other articles for their wardrobe. To the women he brought trinkets, pins, needles, thimbles, thread, and other wares, besides veils, silk handkerchiefs, and perfumery. In a country so lawless, and so often torn by insurrection, it is almost a marvel he escaped being robbed and assassinated; but Stefa was a pattern to all pedlars, a prince among politicians, his good humour was unfailing, he had a kind word and a flattering speech, alike for the wealthy Mahometan of the plain, and the prowling Haiduc of the mountains; and above all, he was a living gazette, circulated all the news of the day, and was without a rival as a singer and story-teller.

My friends in Ocrida and Strouga recommended him very highly, but he would not consent to accompany me, unless I allowed him to attach sundry little packages of merchandize to my saddle. It is true, this gave me the appearance of a pedlar; but in a country without roads, and in mountain districts, where the traveller, who has any regard for the safety of his neck, must occasionally perform the journey on foot, I was indifferent about the matter, particularly as he had a capital pair of horses, and being kind and attentive to their wants, they followed him, and answered his whistle, like a couple of Spaniel dogs.

At the Pass of Keupris, through which runs a torrent of the same name, Hamsa left us, for we were now about to enter the country of the Djeghi Miriditi, presenting an aspect equally wild and desolate as any I had hitherto traversed. There was a little river, like a cataract, tearing its course between a wall of rock with a narrow horse-path before us, resembling a ribbon carried along the brow of an almost perpendicular mountain; it was, in truth, a fearful pass, and might cause the stoutest heart to hesitate before commencing it; but by the influence of habit we become so inured even to the most dangerous passes in mountain travelling, that we fear not to mount a crag or a precipice, which at another time we should shrink from attempting.

On descending through the depths of a defile, equally precipitous, with a half dried-up torrent, we came to the rapid Scoumbi, the Genesus of the ancients, and the Tobi of the Miriditi; having successfully forded the surge, we hurried on to a han, which appeared like an eagle’s nest pending from the brow of the mountain, where Stefa, with his worn-out horses, determined to pass the night. This arrangement was much against my inclination, as I had no wish to be tormented with an additional number of the live stock that infest these resting-places of the traveller in European Turkey. However, there was no alternative, the rocks offered no pasture for our horses, and Stefa felt certain that if we slept al fresco in such a wild district as this, we should run a fair change, if we escaped the prowling bandit, to be devoured by bears or wolves.

Poor Stefa! if he avoided one peril that haunted his imagination, he rushed into another; for on entering the han we found it crowded with a band of fierce mountaineers, armed at all points, on their way to join the rebel chieftain, Julika. The angry look they seemed to cast upon us was sufficient to shake the nerves of a stronger man than our kiraidji, whose ghastly features and trembling limbs indicated that his thoughts were wandering among the contents of his pedlar’s pack. He wisely, however, made the best of his position, and having most respectfully saluted the party by placing his hand over his heart, and saying in Albanian, “Mir ouernata,” accompanied by “aye-schindosh,” (a good evening), and hoping he found his good friends all well, proceeded to place our various packages and saddle-bags under the care of the hanji. His mind being so far at rest, and having exchanged a word or two with the master of the han in an adjoining room, he ventured into the general reception-room, carrying a large bag filled with the finest tutoun (tobacco) and a canister of genuine English powder. This he divided among the warriors, as priming for their guns and pistols, assuring them, with much grandiloquence of style, it was a present from his Serene Highness the Ingleski Bey, his master (what a bouncer!), at the same time hoping they would honour the humblest of their slaves by accepting from him a little tutoun.

Whatever might have been the original intention of these warriors of the phistan, Stefa’s politic manoeuvre won the good-will of all present; the best place in the room was assigned to us, tchibouques and raki were pressed upon us from every side, and we found ourselves as safe in the midst of these wild-looking insurrectionists as if we were under the safeguard of the police of the best-regulated country in Western Europe. In short, the only drawback to my amusement, was my inability to hold converse with our warlike companions, except through the medium of two bad interpreters, Stefa and the hanji – a Zinzar [Vlach], whose native tongue, the Roumaniski, somewhat resembled the Latin.

The chief, or leader of the band, who possessed a most intelligent countenance, strikingly resembled in form and feature a certain nobleman in England, and, like him, was a splendid specimen of man. He expressed himself much interested on finding he had met with a Frank, and told us that, according to tradition, his ancestors were Norman, and possessed vast estates in Upper and Central Albania, previous to the Turkish conquest, the greater part of which they lost during the wars of Scanderbeg and subsequent revolutions. Although a Mahometan, he held the Osmanli in great contempt, whom he denounced as a gluttonous race, without honour or faith; the phrase he used, and which I heard so frequently afterwards in the mouth of an Albanian, was “Osmanlis cinai kalos dia to tchorba!” Poor fellow! I fear he was engaged in a hazardous enterprise, which would probably end in the loss of his life, or at least the remnants of the lands bequeathed to him by his forefathers. On parting, he presented me with a beautiful poniard, the handle glittering with silver and precious stones; and in return, I gave him the last pair of pistols but one out of half a dozen I had brought with me from England, to serve as presents on similar occasions. “Preserve this,” said he, “as a talisman; for should you get into trouble, or meet with any of our bands, you have only to show it, and tell them that you have eaten out of the same dish, drank out of the same cup, and smoked out of the same tchibouque with the Bey Manie of Croia, to find everywhere a friend and protector.”

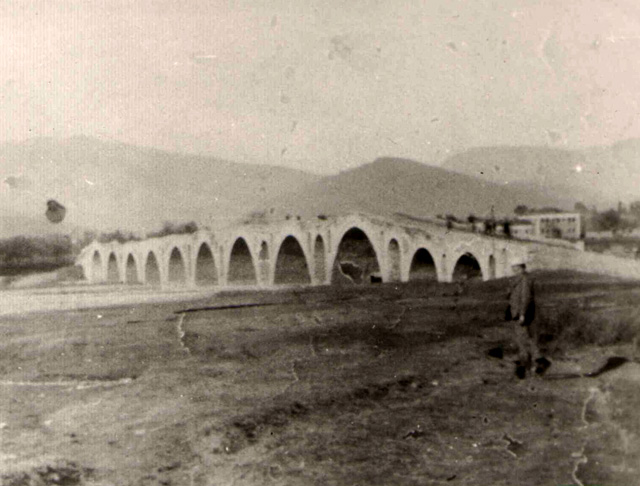

One-time Bridge of Kurt Pasha

near Elbasan.

On leaving the han, the landscape still maintained its character for savage wildness, abounding in gorges, narrow defiles and rocky precipices, till we arrived at the great stone bridge over the Scoumbi, consisting of twelve arches, without a parapet, exceedingly narrow, and with a pointed arch in the centre, rising to a height of at least fifty feet. Altogether it was a singular specimen of bridge building by the ancients, and proves that travelling on wheeled vehicles was not more fashionable then in Albania than in our time. There was an inscription to record that it was repaired by the puissant Seigneur, Kurd Pacha. During my subsequent excursions in Albania and Epirus, I met with other bridges, constructed in a similar manner, but at what epoch, or by what people, has not hitherto been satisfactorily discovered. Some antiquarians believe them to be the work of the ancient Macedonians or the Romans, while others imagine them to have been built by the Byzantine Greeks. In every instance the Turks have defaced the original inscription, with the absurd intention of destroying every trace of the original possessors of the country; and in some cases, they have even placed an inscription, telling the reader it was they who had erected the bridge! What a miracle!

After crossing the Scoumbi, the defile continued to widen into a beautiful fertile valley, splendid forest trees covered the sides of the mountains to the highest peak; meadows and arable fields lined the banks of the river, while many a pretty hamlet lay scattered here and there, half hid by the foliage of the orchard and the forest. As we advanced we entered a fine avenue of plane-trees, of an enormous size, which conducted us to Elbassan [Elbasan], situated in one of the most beautiful and fertile plains in Albania, where the olive and the vine, the fig and the pomegranate, arrive to the highest perfection.

Elbassan, the ancient Bassania, previous to the rule of the Turks was one of the most commercial towns in this part of the world, with a population exceeding fifty thousand, reduced at present to between three and four thousand; altogether, the town presents a melancholy picture of castles, turrets, fortifications, fountains, public buildings, bazaars, and private homes, all lying in ruin. Even the mosque, so generally the pride of the Mahometan, is here fast falling to decay, its crumbling walls affording nourishment to the fig, which is seen spreading its foliage, in company with a forest of stately weeks, alike over the porch and the gilded dome. Even the river, a tributary of the Scoumbi, which once flowed around the town in a clear and rapid stream, now impeded in its progress by mountains of rubbish, caused by the fall of the towers and breaches in the walls, forms a succession of stagnant putrid ponds, exhaling death to the inhabitants who still cling to the hearth of their forefathers; and, to add to their misery, there is not a drop of water to be had for culinary purposes, without resorting to a spring in the neighbouring mountains, from which the Romans, who perfectly understood the value of time and labour, had conducted an aqueduct, now serving as a picturesque ruin to increase the romantic interest of the landscape. We need scarcely add, that Elbassan is the abode of pestilence, sufficiently evidenced by the sickly yellow hue visible in the countenances of the inhabitants; whereas the town, by the removal of the nuisances we have mentioned, might be rendered perfectly healthy, and would be by any other people than these ignorant Mahometans, who appear to live only for the pleasure of doing nothing.

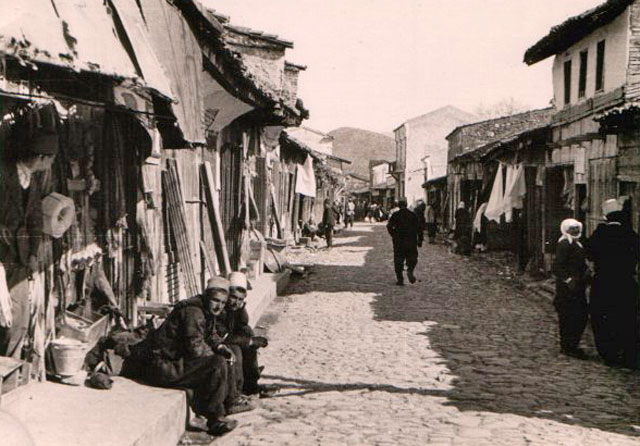

Bazaar of Elbasan in the 1930s

(Photo: Dayrell Oakley-Hill).

Provisions are abundant at Elbassan, and excellent of their kind; fancy my purchasing a fat lamb, ready cooked, for about eightpence of our money! a large basket full of the fiori of the fig, now ripe, and of a flavour superior to those I found in any other country, for less than a penny. Several wealthy Beys and Spahis still reside here; these, with the Turkish Governor, the civil and military authorities, impart something of life to the coffee-houses, the bazaar and the streets, and delight to show themselves attired in the rich, gaudy costume of Albanian warriors, their weapons, glittering with diamonds and precious stones. The greater number of the inhabitants of the town are Mahometans of the Albanian Djeghi tribes. Since the introduction of the reforms of the Sultan, they have lost much of the fanaticism by which they were formerly characterized; and to express their dislike of the rule of the Osmanli, who they hate and despise, they have recently subscribed a large sum of money towards repairing an old church in the town for the service of the Christians, hallowed by the recollection, that within its walls Scanderbeg and the other chieftains of Albania had sworn, on the Evangelists, never to sheathe their swords while an infidel Osmanli desecrated the soil of the fathers.

Notwithstanding the continued insurrections of these warlike tribes of Albania, and their reckless bravery, they rarely succeed in gaining any important advantages over their old enemies, the Osmanli; and even if they could emancipate themselves, we fear that the country would become a prey to the horrors of civil war, in consequence of the rivalry of creeds, and the hostility of tribes. We have only to leave Elbassan, and cross one of the mountains to the south, when we enter the country of the Toski [Tosk] tribes, equally divided in faith – part Mahometan, and part adhering to the Greek ritual; and however much they may dislike each other on religious grounds, they concur in their enmity towards their neighbours, the Miriditi. The same may be said of the Djami [Cham] tribes, that inhabit part of the ancient Epirus, and the Lapi [Lab], the Acroceraunian mountains on the sea-coast. Nor are these the only tribes that call Albania their home: the shrewd Zinzar, and the laborious Bulgarian, are increasing in numbers and influence; in addition to these we find Hellenic Greeks, Armenians, Jews and Gipsies, forming such a confusion of tongues, and rivalry of tribes and creeds, as to preclude the prospect of any union of interests in the present day.

The Mahometan-Albanians, of whatever tribe, at least have the merit of being actuated by patriotic motives, and a love of independence; whereas the Christians, influenced by the arts of designing priests, in addition to their unnatural hatred towards each other, are traitors to the independence of their country. The Albanians of the south, the Djami, who adhere to the Greek ritual, desire a union with their co-religionists of Modern Greece, King Otho’s little kingdom; while those of the north, the Miriditi, who follow the Latin creed, regard the Roman Catholic Sovereign of Austria as their spiritual and temporal chief. This is the true cause why a country so admirably defended by nature, and inhabited by a people not surpassed by any other in bravery and love of liberty, has remained so long under the rule of the Osmanli. We have seen the Djami, the unhappy Christians of Souli and Parga – a mere handful of men – successfully defend for years their freedom and mountain home against the overwhelming forces of the Mahometan-Albanians under Ali Pacha of Jannina, without their neighbours, the Toski or the Lapi, their co-religionists and countrymen, raising a single arm to assist them.

The Miriditi, both Mahometans and Christians, whose territory, the ancient Djegharia, includes nearly the half of Albania, are, from position and numbers, by far the most powerful of all the Albanian tribes, and continue to maintain, in the fastnesses of their native mountains a sort of wild independence, never submitting to the harritch nor the conscription, unless by force of arms; and now that their old rivals, the Toski and the Djami, have been nearly exterminated during the dreadful rule of Ali Pacha of Jannina, should the Mahometans Miriditi at any time, through political motives or conviction, return to the creed of their fathers, and make common cause with their brethren, the Latin Miriditi, they might succeed in driving out the Osmanli and bringing the whole of Albania under their subjection. To aid them in this, they possess a long line of sea-coast, with towns and harbours, particularly Scutari [Shkodra], together with the old town of Croia [Kruja], the ancient capital of the Kings of Albania, always a prestige in their favour. They have also the advantage that a large portion of these tribes, to which we have before alluded – the Latin Miriditi – are wholly independent of the Ottoman Porte, and have been governed since the days of Scanderbeg by their hereditary princes, at whose little capital, the mountain town of Oros [Orosh], the crown of Albania is still preserved.

Fighters near Elbasan,

Ottoman period.

We regret that the limits of this work will not permit us to enter into the history of these warlike tribes, the Latin Miriditi, who, like the mountaineers of Tchernegora [Montenegro], have continued for centuries to defend their mountain home against the most powerful armies of the Ottoman Porte. It is true there is not a single pass leading from the lowlands where an army could advance without danger of being annihilated by a people who are hereditary guerillas, and who inhabit a natural citadel surpassing in strength all that human skill and foresight could construct. As Englishmen, we cannot but admire the heroic spirit of these noble patriots! who, when they had been defeated in the plain, took refuge on the mountain, where they could at least be free, and follow the faith of their fathers; and how many privations must they not have endured! – how many generations passed away, before they could even procure a scanty subsistence from the sterile soil! And what a proof is here exhibited of man’s industry and perseverance: the home of the bear, the wolf and the boar, on which grew the noisome weed and prickly shrub, we see now transformed to gardens and corn-fields; and on the mountain top, where the eagle and the vulture reigned supreme, we behold innumerable flocks of sheep and goats.

It is a popular saying among the inhabitants of European Turkey, of whatever nationality or creed, “Where the Sultan’s horse hath trod, the earth yieldeth nought save thorns and thistles!” and truly, we have only to wander over the mountains, of whatever district, and then descend to the plain, to be convinced of the truth. And how melancholy! Wherever we roam in this lovely country, we see the finest land lying uncultivated for the want of inhabitants: here the remains of entrenchments, there the ruins of churches, forts, towers, towns and cities, telling the fearful tale of the thousands who had died in their attack and defence. With so many objects to remind the inhabitant of the destroyer, whose descendant is still their Sovereign, can we feel surprised at the intense and bitter hatred they bear towards the race of Othman, to whose barbarous administration they owe all their misfortune. Albania, as elsewhere in these provinces, is still without any other roads than those left by the Romans; the rivers without bridges, and the towns and cities fast falling into ruins; and to increase the discontent of the Mussulman population, since the introduction of the conscription, they are hunted down like wild beasts, to swell the ranks of the Nizam-y-Djedid, or expatriated in thousands to colonize some disturbed district in Asia or Europe. Thus torn from the soil of their fathers – their best affections trampled upon; district after district burst forth into those annual revolts, which are never put down without great loss of life, and the hot blood of the Albanian is fired anew, with the never-dying thirst of revenge.

Unhappily, the picture we have drawn is too true, and at once explains the rapid diminution of the population of Albania, which previous to the rule of Ali Pacha of Jannina, contained two millions and a half. The wars and massacres of that tyrant destroyed, it is presumed, half a million; then came the reforms of the Sultan, and the insurrection of the Beys, and their slaughter by the Grand Vizier, Mehemet Reschid Pacha; this horrible event was succeeded by the rebellion of Moustapha Bey of Scutari, who, supported by Austria and Russia, fought long and successfully for the crown of Albania, till betrayed by his two allies, when they found it their interest to disown him, he was obliged to give way to a superior force, and Albania had the misfortune to be over-run by an army of its own children, who, though Christians professing the Greek ritual, battled side by side with an army of infidels. The reader will not be surprised, after perusing this hasty sketch, to learn that the population of Albania is now diminished to one million six hundred thousand.

CHAPTER VOrigin of the Albanians – Their warlike tendencies – Creed, manners and customs of the Albanians – Feudal institutions – Hereditary chieftains – Austrian politics in Albania – Sketch of Mahmoud Baraklia – Contemporary history of Albania – Insurrectionary movements of the Mussulman-Albanians – Their wars with the Turks – Sketch of the Grand Vizier, Mehmet Reschid Pacha – Cruel policy of the Turkish Government in Albania – Horrible slaughter of the Albanian chieftains at Bittoglia – The conscription – Its demoralising effects – Great discontent among the people – Difficulty of governing Albania.

Notwithstanding all the efforts of the learned and antiquarian since the days of the Greeks and the Romans, the origin of the inhabitants of Albania still remains disputed point; it is, however, pretty generally agreed, they came from the Caucasus. This supposition is strengthened by the fact, that there are tribes still existing on the banks of the Samour in the ancient Albania, bearing the names of the Toxidi and Dmjaki, which correspond with the Toski and the Djami tribes of our Albania. The appellation of Miriditi, by which the Djeghi tribes, particularly those who adhere to the Latin ritual, are more generally known, is derived from a word in the language of the Medes and Persians – Marditi (brave), simply a title of honour, like Slavoni and Germani (men of war). It is presumed that the expedition of Jason to Cholchidus, having irritated the Caucasian tribes, they retaliated by invading these provinces, where they reigned from sea to sea; this theory is corroborated by the fact, that several ancient towns, rivers, districts and mountains, still preserve their Albanian names. On the other hand, one or two German writers contend that the Albanians are the aborigines of these provinces, whence sprung the Greeks, Illyrians, and Slavonians; this we think must be erroneous, since the Albanians of the pure race, the Skipetar tribes (inhabitants of the mountains), bear no resemblance in feature, character or language, to the Greeks or the Slavonians; they are more like the Lesghi tribes in the Caucasus and on the Caspian Sea, than any other I am acquainted with. They are characterized by the same expressive, sharp features, tall, athletic figure, capable of enduring any fatigue, and like them, they exhibit the same indomitable spirit of resistance to the rule of the stranger, and the same love of independence.

When the whole of Greece and the neighbouring provinces submitted, first to the Romans, and then to the Osmanli, Albanian was destined to be the last home of liberty; for neither the eagle of the one, nor the crescent of the other, ever waved over the mountains of the Skipetars; neither has mighty Russia, after a siege of fifty years, been able to reach the strong hold of the Caucasian Lesghi. Like the Caucasians, it has been noticed, wherever the Skipetars of Albania have mingled with any other race, they have imparted to them their own inflexible character – their warlike enthusiasm. The Djami tribes of Souli and Parga, already immortalized in verse, were a mixed race of Albanians and Greeks, and their neighbours, the indomitable mountaineers of Tchernegora, are also a mélange of the Slavonian and Albanian. Still there is a singular anomaly in the character of the Albanian, since we find him in every epoch submitting to be made the tool of some tyrant stranger, whether Greek, Macedonian, Roman, or Turk, to enslave the nations: his energy in the battle-field rendered the Turk the terror of Christendom; yet, of all the great warriors Albania has produced, not one except Scanderbeg has transmitted his name to posterity, owing to the facility with which these people, when they leave their native mountains, mingle with other races, and merge their individual name and glory in that of their rulers.

Among the long catalogue of successful warriors and celebrated viziers and pachas, whose names adorn the pages of Turkish history, there are few who were not natives of Albania and Bosnia; and although the Albanians have been stigmatized for their ferocious disposition and predatory habits, we must not infer they are naturally cruel, when we remember they were instruments of a most unscrupulous government, who paid its troops by allowing them to plunder, and considered the best test of a warrior’s prowess consisted in the number of ears he was able to produce at head-quarters. Let the stranger visit any one of them, of whatever creed – the wealthy inhabitant of the koula, or the miserable tenant of the hut – and he is certain to find a hearty welcome among a people who regard hospitality as the first duty of man towards man, and who would sacrifice their own life in defence of him who had broken bread with them, or even smoked the tchibouque.

In order to study the manners and customs of the Albanians in all their purity, we must visit the independent tribes of the Miriditi in their mountain stronghold, where the hostile foot of the Osmanli never trod, where we shall find the same feudal institutions existing as in the days of Scanderbeg, somewhat similar to the state of the highlanders of Scotland in the middle ages. The title of chief is hereditary, and he is invested by his clan with the tribal authority of chief, judge and patriarch. As chief, he declares war and leads them to battle; as judge, there is no appeal from his decision; and as patriarch, he governs the church. Each noble family has its armorial ensign, and each tribe its respective banner, confided to its warriors when they set forth on a military expedition; and however great may be the power of the chieftain, and the confidence reposed in him by his clan, it is rarely abused. He lives among them at his koula with the utmost simplicity of manners, regards them as his children, and provides for their wants.

A community, in which the whole power was vested in the sword, must have ended in complete anarchy – a war of tribes, had not these people the good sense to adhere to the monarchical form of government of their forefathers, and preserved through every vicissitude and suffering an unbroken allegiance to their hereditary princes, the Dodas, one of the descendants of the family of Scanderbeg. This Prince, who resides at Oros, a little town in the canton of the Doukagini, not far distant from Croia, surrounded by the higher clergy and the most influential elders of the land, exercises the rights of a sovereign, and maintains the form and machinery of a government.

It must be admitted, that the Miriditi mountaineers owe much of the civilized habits of social life to the higher clergy, who are all natives of Austria and Italy; but, unfortunately, they have trained these poor simple people, through political motives, to the most deplorable fanaticism, which leads, as we before observed, to those terrible encounters with their neighbours, the Slavonians of the Greek Church of Tchernegora, a people equally brave and fanatic as themselves; while the Mahometan claps his hands and cries: “Well done, my Latin wolves and Greek dogs, worry each over! – you will then become more easily the prey of the lion Osmanli!” The consequence has been, that the Miriditi have now not only to contend against the Crescent, but the incessant hatred of an insidious enemy, the Greek, who is gradually placing their mountain home between two fires – the Slavonian Greek to the north, and Albania Hellenized to the south.

Reckless of life, confiding by nature, and hence ever liable to be deceived, an Albanian, of whatever tribe or religious creed, is easily won over to the opinions of a clever adventurer, who desires to make him his instrument for furthering his own selfish designs. While we are discussing the social organization of the people, we shall relate a few episodes in their contemporary history, which are partly, if not wholly, unknown to the inhabitants of Western Europe, illustrative of the character of the people; their rulers, the Osmanli; and their dangerous intriguing neighbours, the Austrians and Russians.

About the year 1786, the Austrian Government, under the plea of protecting its co-religionists, the Miriditi mountaineers, for the first time interfered in the internal affairs of Albania; and having singled out Mahmoud Baraklia, hereditary Pacha of Scutari, as its instrument, offered to support and acknowledge him as sovereign of Albania, provided he would be baptized and adopt as his creed the Roman Catholic. There was no difficulty in winning over a man who had already, by many of his acts and alliances with the Latin chiefs of the Miriditi, made himself suspected by the Ottoman Porte, which however did not find itself strong enough to send the Capidgibaschi with his bow-string to visit a man who exercised the rights of a petty sovereign over the most numerous and valiant of all the tribes in Albania.

In vain the Sultan sought to retain the ambitious Pacha in obedience, by promises of boundless wealth and advancement to the highest dignities in the empire; in vain the Scheick-Islam launched anathema upon anathema against the Giaour Pacha and his adherents; he remained firm to his purpose, and daily became more and more the idol of the people. In the meantime, Joseph II., who was then the sovereign of Austria, sent his first contingent of five hundred veteran soldiers to the assistance of the rebel chieftain, these were to be speedily followed by fifteen hundred, and that the new creed of this protégé should not want for a stimulant, they were accompanied by a legion of priests bearing an enormous silver cross, and a Madonna blazing with diamonds and precious stones. The black eagle, in a crimsoned field, the banner of Scanderbeg, was now unfurled, and consecrated by the Roman clergy, in presence of an army of twenty thousand eager warriors, whose vivats proclaimed – Mahmoud of Scutari, the descendant of Scanderbeg, sovereign of Albania.

While these events were passing at Scutari, a Turkish fleet arrived in the Adriatic to blockade the coast of Albania; at the same time, a Turkish army, under the commander of the Seraksier, Vizier of Roumelia, having crossed the dangerous passes between Macedonia and Albania, and joined the Toski and the other fanatic Mahometan tribes of Albania, fell with fire and sword upon the devoted land of the insurgents with an impetuosity that promised to carry all before it. The terrified Mahmoud, astounded at the extraordinary vigour displayed by the Ottoman Porte, repented of his precipitancy, and shutting himself up with his Austrian allies in the strong town of Scutari, entered into a secret negotiation with the Seraskier. But his other allies, the Roman Catholic Miriditi of the mountains, strong in their unity of one common creed, with a firm reliance on the sincerity of their chief, and strangers to political intrigue, having joined their brethren of the lowlands, at the first onset made themselves masters of the passes leading into Macedonia, and with their usual reckless bravery, fell upon a division of the Vizier’s best troops and drove them towards the pass of Ocrida, when, finding all hope of safety was at an end, they threw down their arms and fled, communicating a panic to the entire army of the Seraksier.

We are afraid to enumerate the loss of the Turks and the Mahometan Toski, during this fatal action, which the Miriditi, exultingly say, equalled that of the greatest victories ever achieved by their hero Scanderbeg.

The character of Mahmoud Baraklia – or, as he is netter known in Turkish history, Kara Mahmoud – is open to much reproach; and however illustrious his descent might be – from the hero Scanderbeg – he was no soldier; and subsequent events proved that he was either a fool, or a traitor to the unsuspecting tribes that so madly followed his standard. Instigated on one side by the Sultan, who must have been desirous to see the fall of so ambitious a chieftain, he was offered the doubtful sovereignty of the free tribes of Tchernegora, with the territory of the Latin Miriditi, and Scutari, as a sea-port; on the other hand, Austria, who could not view with complacency the growing power of a little State devoted to the interests of Russia, promised him her protection and assistance. Fortified in his invasion by the Imperial rights of the Sultan, who had accorded to him the sovereignty of Tchernegora, and hallowed by the blessing of the Romanist clergy that followed his standard, the too sanguine Pacha, who fancied he could succeed in any enterprise, however, difficult, at the head of his valiant Miriditi, entered at once into their views. The Christian Miriditi, also, flushed with victory, and excited to madness by their priests, who told them they were the chosen soldiers of the true faith, and that in extirpating the schematics of Tchernegora, they were only executing divine vengeance on heretics, were ever the foremost among his troops.

Now it happened that the schismatics of Tchernegora were equally intolerant, and had also their priests, who propagated similar fanatic opinions to those of their rivals of the Latin Church. We will spare the reader the details of the horrible butcheries that ensued; the Tchernegori mountaineers, more prudent than their adversaries, the Miriditi, allowed them to penetrate into the interior of their mountains as far as Tchetini [Cetinje], where they were surrounded by an implacable foe that gave no quarter, and, as a memorial of the victory, Mahmoud Baraklia’s head still adorns the hall of the senate-house.

The tragic death of the old lion Mahmoud, as he is familiarly called among the Miriditi, and the losses his party sustained in this fatal conflict, induced his son and successor, Moustapha, to submit to the authority of the Sultan; and as a proof of his fidelity, the Austrian troops were discharged, and the heads of the principal conspirators, particularly that of Signor di Brognardi, the Austrian agent, were sent to consol the Divan at Stamboul.

The complete disorganization that ensued among the Miriditi after this fatal defeat, excited the ambition of all the Beys and chieftains of the other tribes of Albania, who aspired to supreme power. Among these there was none that knew how to profit by the events of the day like Ali Pacha of Jannina. The singular career and tragic death of this adventurer, who from a captain of banditti became a despotic ruler, are too well known to require description; it will sufficiently connect the thread of our historical sketch to say, that the theatre of his massacres, devastations, and tyrannic rule, being principally confined to Southern Albania among the Toski, the Djami, and the Lapi tribes, their fall, with that of their leader, paved the way for the young lion, Moustapha of Scutari, and his Miriditi, Christian and Mahometan, to become again the ruling tribes of Albania.

At the death of Ali of Jannina, the Ottoman empire tottered to its foundation, and may be said to have owed its safety to the state of barbarism in which the country was sunk, for, as is the case in the present day, no means of transmitting letters, or communicating any intelligence existed, either by post or printed publication; consequently the inhabitants of one province were entirely ignorant of what occurred in another. This isolation of the disturbed districts prevented the insurgents from acting in concert, and the magnitude o the danger passed over.

Mehemet Ali, of Egypt, ruled independent of the Ottoman Porte, the principality of Servia was nearly so; while Moldavia and Wallachia, instigated by the agents of the Greek Heteria, broke out into rebellion about the same time as Greece. The plan of a simultaneous rising of the entire Rayah population of European Turkey, solely failed through the revival of the old hatred between the rival races, Greek and Slavonian, in which neither would submit to be ruled by a chieftain of the other. It was of no avail that they professed the same creed – always a rallying point to races, however distinct they may be – the ancient hatred of the Slavonian to Greek perfidy, Greek levity, and the traditional recollection of what their forefathers had suffered under the Byzantine rule, remained in full force. The consequence was, that not a single Slavonian, with the exception of Botzaris and one or two others, raised an arm or subscribed a piastre towards assisting the unhappy Greeks during the tragic scenes that ensued.

Hitherto Sultan Mahmoud held in his hands a dreadful scourge; wherever there was a people to be coerced, a country plundered, he found his ready instrument in the warlike Mahometan hordes of Albania and Bosnia – a military force, which while it did not cost him a farthing, sufficed to hold in check the reckless bravery of the Christian insurgents of Servia, Greece, and the other provinces on the Lower Danube. By the slaughter of the Janissaries, a measure at that moment most impolitic, since he had not an effective force to replace them, he lost the sympathy of these warriors of the Crescent.

This was succeeded by the introduction of European reforms and usages repugnant to the habits of the people, which led to the insurrection of the Beys and Spahis of Albania and Bosnia, and which has continued with more or less activity down to the present day. At a moment so menacing to the existence of the Ottoman empire, Russia declared war; and Austria, who always goes hand in hand with her northern ally, if she did not assume a position actually hostile, resorted to her usual weapon – intrigue, with the view of securing to herself Albania and Bosnia, in the event of a dissolution of the rule of the Sultan – provinces so admirably adapted to round her already extensive empire. The Roman Catholic Miriditi mountain tribes were wholly devoted to her cause; and could Moustapha Bey of Scutari, be gained over to place himself at the head of the movement, success was certain.

The same propositions, formerly accepted by the unlucky father, were now made to the son; and Russia being at this time deeply interested in the ruin of the Sultan, offered to support him, conjointly with Austria, as Sovereign Prince of Albania. The misfortunes of the father had taught his more wary son prudence. He saw that he was merely intended to be a puppet in leading strings, to be danced according to the interests of the astute politicians of civilized Europe. Thus, while the other Beys of Albania were engaged in a war of extermination, each hoping to rise to supreme power on the ruin of the other, Moustapha and his Miriditi remained passive spectators of the scene.

Unhappy Turkey! the good genius of Othman had not wholly deserted his race. At this critical moment a hero of a different mould, from the degenerate Osmalis of the day, was chosen by the reforming Sultan as his Grand Vizier. This was Mehmet Reschid, so well known for his fidelity to the late Sultan Mahmoud, and to whom we have had occasion to refer while travelling in Bosnia. In addition to being gifted with all the ancient fire and energy of his race, he was a zealous Mahometan; firmly believing that any act, however, cruel, was sanctified when emanating from the Sultan, who alone inherited the prerogative to make or unmake, to bind or to slay, according as the exigencies of the moment might dictate. In short, our Grand Vizier was one of those bigots who confided so absolutely in the divine wisdom of the Caliph of the Faithful, that had Sultan Mahmoud declared himself a Christian, he would have following him in his heresy, and propagated the tenets of the new doctrine with the same fervency and devotion which now distinguished him in his ruthless crusade against the enemies of reform; and in no part of the Turkish empire, not even in Bosnia, was there manifested so decided a hostility to change, as among the high-born conservative of Albania, whose rallying cry was “Death to the Giaour Sultan!”

However gloomy appearances might be, the wary Vizier was prepared for every emergency. In the poetic language of his race, he knew he held in his hands a bridle to cheek the fire of the Mahometan steed; and though the measure might be opposed to the laws of the Koran, he determined, having the sanction of the Caliph, to put arms into the hands of the Rayahs, who everywhere sided with a government which secured to them civil and religious rights equal to those enjoyed by their hereditary oppressors, the Mahometans. It is true they suffered severely at the commencement of the conflict, but it was attended with important results, since it taught them the art of war, improved their moral condition; and for the first time they became aware of their own strength, bravery and numbers.

Watercolour of the Agai Mosque

in Elbasan (Fadil Pullumbi, 1971).

We have said that the whole of the Mussulman Beys of Albania, with the exception of Moustapha, the prudent chief of the Miriditi, were in open revolt against the authority of the Giaour Sultan. The Grand Vizier, while he flattered this powerful chieftain, resolved to sow dissensions among the other Beys of the Toski, the Lapi and the Djami; this, however, could not be done without funds, and there was not a piastre to be had from the Turkish exchequer, already drained of its last coin, which went to purchase peace from Russia; and to add to the embarrassment of the executive, civil dissensions and insurrections were not confined to Albania, but everywhere rampant throughout the entire empire. With consummate ability he addressed himself to the high dignitaries of the Greek Church, whose esteem he had won by timely and important concessions; painted to them the situation of the empire, and the probability of their own ruin, with that of the reforming Sultan, should the fanatic Mussulmans again succeed to power. The appeal had the desired effect. A pastoral letter from the Patriarch of Constantinople to every diocese in the empire, produced an immense collection from the Christians.

The Grand Vizier, now so opportunely supplied with the sinew of war, instead of repairing to the scene of action, although he lay at Bittoglia [Bitola] with a large force of the tacticoes, together with the adherents of those Beys, Pachas and Spahis attached to the cause of reform, continued to fight the battle in Albania with his usual weapons – corruption and intrigue – best suited to a people who were invincible so long as they remained united. With great tact, he gained over to the cause of reform the most powerful and valiant of the chieftains, Veli Bey, who held possession of Jannina and the whole of the intermediate country, with the strong towns of Arta and Prevesa, and who, in conjunction with the Epirot Christians, successfully maintained himself against the refractory Beys.

The astute Asiatic, who secretly entertained the design of exterminating all the feudal Beys and Spahis in Albania, as he knew that so long as they existed there could be no hope of introducing the reforms of the Sultan, having succeeded in kindling the torch of civil war, under the pretence that his religious feelings, as a good Mahometan, prevented him from spilling the blood of the faithful, obstinately refused to take any part in the struggle. This forbearance on the part of the Grand Vizier gained him the esteem of the contending chieftains, who, at length weary of the contest, and acted upon by clever agents, consented to leave their grievances to the decision of the high-minded, peace-loving representative of the Sultan.

The web of intrigue, so artfully woven by the Grand Vizier, was now about to be drawn around his unsuspecting victims. With his usual blandness of manner, and expressions of delight at the termination of their disputes, he, in the name of the Sultan, granted all their demands; and in order to bind their union still more closely, he invited to his camp, at Bittoglia, all who were desirous of distinguishing themselves in the service of the state; and if Albania did not contain a sufficient number of Pachaliks, Beylouks and Spahiluks, was not the empire large enough to satisfy their utmost ambition! On the receipt of this gratifying intelligence, the whole country was in a ferment of delight; rival chieftains, with their clans, fraternized, and in the excitement of the moment, four hundred of the noblest chieftains in Albania, all hereditary Beys, full of confidence in the faith of so good a Mahometan as Mehmet Reschid, repaired to Bittoglia, to receive their investiture of office. They were met on the frontier by a guard of honour, who had orders to conduct them in state to the presence of the representative of the Sultan. On arriving in Bittoglia, they were received with the highest military honours; a feu-de-joie announced their approach; the tacticoes were drawn out in full parade on the At-meidan, and on they rode, full of hope, arrayed in the brilliant costume of Albanian chieftains, through a double hedge of bayonets, towards the kiosk of the Grand Vizier, who was seated under its tchardak, surrounded by a crowd of civil and military officers, waiting to receive them. No sooner, however, had the last ill-fated victim of Osmanli treachery, entered the serried ranks of the soldiery, than at a signal given by the Vizier, the drums beat the charge, and instantly a discharge of musketry, sufficient to rend a mountain, laid that brilliant band of warriors – the pride and strength of Albania – in the dust.

One noble fellow, Arslan Bey, whose quick eye saw the signal given by the Grand Vizier, suspecting treachery, at a bound of his horse, cleared a passage over the heads of the soldiers. In vain he strained his noble charger! in vain he reached the pass leading to Albania! he found it in the hands of an enemy that gives no quarter!

The destruction of the hereditary Beys and chieftains of Southern and Central Albania, opened a wide field of ambition to the Miriditi of the north, who on receiving intelligence of the massacre, rallied around the standard of their chief, Moustapha, and with loud cried demanded to be led against the treacherous Vizier. Scutari, with its castle, Rosapha, again rang with the clang of arms, and again the banner of Scanderbeg replaced the Crescent. The indignation of the Mahometan Miriditi was equally shared by their generous countrymen of Latin creed, who flocked in thousands to the standard of Moustapha, now without a rival, the Sovereign of Albania.

At the head of thirty thousand men, the Miriditi chieftain carried all before him, town after town, fortress after fortress, opened their gates to the conqueror; but, as is ever the case with these savage warriors, pillage, devastation and slaughter everywhere marked their progress; and, eager to revenge the massacre of their brethren, they put every Mahometan of Osmanli origin to the sword, together with every Rayah professing the Greek religion, who was found bearing arms, or known to have taken part with the Government of the Grand Vizier, in the late struggle between the rival chieftains.

The Grand Vizier, who had made himself so unpopular by his wholesale destruction of the Beys of Albania, appears not to have foreseen the hostility of the Miriditi tribes, particularly the mountaineers adhering to the Latin creed, the most valiant and the most to be dreaded, on account of their independent habits and union. As to the traitor, Moustapha, the worthy son of a foolish, vain father, subsequent events proved that he was nothing more than an unwilling agent in the hands of this own troops, and that he was playing, from first to last, into the hands of the Grand Vizier. Still the peril was great; a single false step at this moment and all was lost. The Mahometans in every part of the empire were wavering in their allegiance to the Sultan. Bosnia was in open rebellion; twenty thousand fanatic Mussulmans, under the command of the Zmai od Bosna, were advancing from that province to meet the Albanians on the plains of Macedonia, who were then to march on Constantinople, and dethrone the Sultan. In the face of these evils, it cannot be wondered that even Mehmet Reschid, however fertile in expedients, now trembled at his own temerity; he saw that he had merely shorn a few heads, to erect in their place a hydra more powerful, and far more impatient of Osmanli rule. There was one path still open to him: “The Christian dogs, were they not also divided in faith, Latin and Greek, the most inveterate enemies of each other; if the Latin hound has made common cause with his brother, the Djeghi wolf, we will let loose upon them the Greek tigers of Epirus!”

The thought was worthy of Mehmet Reschid, the Grand Vizier; an appeal was made, by his emissaries, to the patriotism of the Osmanli, who were told that the renegades of Bosnia and Albania had sworn the destruction of every Osmanli in European Turkey; at the same time, the excesses of the Miriditi Latins were magnified to the tribes professing the Greek religion, who were made to believe that they had sworn the massacre of every Christian differing from them in faith; and the atrocities perpetrated by these tribes, when employed by Ali Pacha of Jannina, against the unfortunate schismatics of Souli and Parga, were too recent to be forgotten.

The appeal to the passions of the Osmanli, and the schismatic Greeks, produced the best results – they both rallied around the standard of the Grand Vizier; the latter even exceeded the Osmanli in devotion, for they not only contributed men, but money – half a million of piastres – towards carrying on the war; this, with a sum of money sent by the Sultan, enabled the energetic Grand Vizier to set his army in motion, and march upon Prilip, where the traitor, Moustapha, without even securing the passes leading to Bittoglia, was spending his time in giving costly banquets to his troops. The open camp and ill-defended town were carried at the point of the bayonet; at the first shot Moustapha fled, but the Miriditi Latin mountaineers, and the schismatic Greek Skipetar, now face to face, fought with all the hatred of fanaticism, and the slaughtered Souliots were at length avenged.

In a country like Turkey, where the record of events, even the most recent, is confined to the oral tradition of the people – the songs of the bard, exaggerated, or distorted, according to the feelings of the interested party – it is difficult for the stranger to arrive at a real statement of facts. Knowing this, we have never ventured to put forth a single historical statement, that was not confirmed to us by some respectable Jew, Armenian, or Frank merchant settled in the country.

Among the Miriditi of the Latin creed, and the Mahometans of Albania in general, the name of the traitor, Moustapha, is still a by-word of reproach and horror; on the other hand, his friends maintain that he fell a victim, like many others, to the dark policy of the Grand Vizier, who succeeded in corrupting a sufficient number of chiefs under his command, so as to ensure a certain victory. Be this as it may, on leaving the field of battle he shut himself up in his strong castle, Rosapha, at Scutari, where he still defied the Grand Vizier, and only capitulated on receiving a full pardon, and a guarantee for the security of his private fortune, when he engaged to deliver all papers, and reveal every secret treaty or agreement which tended to criminate Mehemet Ali, of Egypt, or any foreign power. It was now discovered that both his father and himself had been the pensioners of Austria for more than half a century, and that he had entered into a treaty with Mehemet Ali for the dethronement of Sultan Mahmoud. It appears, that the ambitious Pacha of Egypt was to have had the lion’s share, Constantinople, Greece and Asiatic Turkey; while Moustapha himself, and Milosh, Prince of Servia, were to divide between them the remainder of European Turkey. In the fall of Moustapha, we record that of the last hereditary chieftain of Albania, and like the other fiefdoms of bygone days, the Sultan reserves to himself the appointment of a civil governor. Moustapha, however, contrived to secure his private fortune, lives in affluence at Stamboul, and like a good Mahometan, having visited Mecca, now prefixes Hadji to his name instead of Prince.

The Grand Vizier, who was now at the very zenith of his glory, was suddenly called away to arrest the progress of Mehemet Ali, who had already assumed the sovereignty of Syria, and threatened Stamboul. The intriguing Vizier, who had so successfully triumphed over the untutored sons of Albania and Bosnia, found the rule of Egypt a man of a different stamp, whom neither honeyed words nor splendid promises could divert from an enterprise; and to add to his misfortunes, the Nizam, who had triumphed over men having no better weapon to oppose against the bayonet than the unwieldy Arnoutka gun, the sword and pistol, when they saw the steady march of the Egyptian army bristling with steel, fled in disorder, leaving the poor Vizier a prisoner in the hands of the enemy. Here ended the career, military and political, of a man who will be long remembered in Turkish history.

It is generally admitted, that the Grand Vizier, Mehmet Reschid, saved the Turkish empire from imminent peril, if not total ruin, by the dexterity he displayed in separating the insurgents of Bosnia and Albania, before Mehemet Ali had time to advance on Constantinople. By the destruction of the Mahometan Beys of Albania, and subsequently that of Moustapha’s army, he struck at the very root of the insurrection, and damped for a time the military ardour of the most dangerous and warlike tribes in the Turkish empire; but recollection of his perfidy and cruelty, which have sunk deeply into the hearts of the people, and utterly annihilated all confidence in the faith of their rulers, may at some future period be attended with serious consequences. They are now quite as impatient of Osmanli rule and its reforms, as they were previous to the administration of the Grand Vizier, and have proved, during the partial insurrections of 1836, ’40, ’43, ’45 and ’47, when they beat the Nizam in so many encounters, that they merely need a union among themselves, and a proper understanding with their compatriots, the Christians, to become a formidable enemy to the Turkish Government.

The turbulent Toski, who so long fought, bled, and supported Ali Pacha of Jannina, have suffered the most severely of all the tribes of Albania. This splendid race, in every epoch impatient of the rule of a stranger, and whose chiefs were for the most part slaughtered at Bittoglia, are still the heart and soul of every insurrection that desolates this unhappy country. Their women, with the eye of a gazelle, and the limbs of an antelope, at once graceful and haughty, yet full of feminine loveliness, cannot fail to win the admiration of the traveller, however mean may be their attire, however miserable the ruin in which they live, once perhaps the turreted castle of an hereditary chieftain.

The Lapi, who occupy the Kimariot mountains to the west of Epirus, down to the Adriatic, are less numerous than any other of the tribes of Albania, and none are so barbarous or ferocious in their customs and manners. In the time of Scanderbeg they professed the Latin creed, and were included among his confederation of the chiefs and their clans in Albania. Shepherds for the most part, and inhabiting a sterile mountain district, they live isolated, in a great measure, from all communication with the other tribes, and their creed, for the want of spiritual teachers, is a singular mixture of the Christian and Mahometan; those who reside in the towns and villages on the sea-coast conform to the Greek ritual. These mountain tribes pay no tribute to the Porte, nor supply a single recruit to the conscription, without being compelled by force of arms; and such is their hostility to the Osmanli troops, who garrison the few forts in the vicinity of their mountain home, that I was assured not a single Turkish soldier can wander beyond the reach of their cannon, without danger of being shot.

The Miriditi tribes, both Christian and Mahometan, who seem to multiply and gather strength according to the magnitude of their disasters, still maintain their rank as the most powerful of all the tribes in Albania. Since the expulsion of the traitor, Moustapha, these people have become more national, and having so long and faithfully battled side by side, in their struggle for independence, the ancient sectarian animosity has in some measure given way to a more friendly feeling. […]

That great discontent prevails in Albania, as well as in the other provinces of European Turkey, is an undoubted fact, which ever must be the case in those countries when the Government is exchanging the barbarous rule of centuries for some approach towards a civilized administration; then the executive must of necessity sacrifice the interests of the few to the well-being of the many. In one place we have the Mahometans, headed by their hereditary chieftains, endeavouring to recover by force of arms their lost rights and privileges; in another, the Slavonians and Hellenic Greeks, still subject to the debasing servitude imposed on the Rayah – the poll-tax and other grievances, from which the Mahometan is exempt – have become weary of Turkish rule, and plot sedition; and perhaps not the least among these grievances, and of which they loudly complain, are the grinding taxes, levied upon them by their high clergy and countenanced by the Turkish Government, who regard them as civil officers, and make them accountable to the executive for the obedience of their flocks. If to all this we add an occasional razzia made upon their property by some rapacious Mahometan in power, we cannot wonder that they occasionally resort to arms in self-defence.

With so many evils to combat, so many races and creeds to conciliate, the Turkish empire requires an able hand at the helm to steer its course with safety; still the Turkish Government displays much vigour in subduing apparently insurmountable difficulties, albeit, in a somewhat ruder style than we are accustomed to in the West. In every point of view we wish the Sultan success in carrying out the Herculean work of reform his father, Sultan Mahmoud, had the courage to commence, and which has more than once reduced the empire to the brink of ruin. We wish him success, through motives of humanity, knowing as we do, that the evil passions – fanaticism and rivalry – of so many races and creeds, must, on the dissolution of Osmanli rule in these provinces of Turkey in Europe, lead to a fearful state of anarchy.

CHAPTER VIAn original – The Albanian language – Commercial capabilities of the country – Its navigable rivers and lakes – Supineness of the Turkish Government – Defects as a ruling power – Sketches of the country – Durazzo – Croia – The Doukadjini – Oros – Alessio – Scutari – Its lakes and rivers – Singular abundance of fish – The Bocca di Cattaro – Its description as a naval station – How it fell into the power of Austria – Blockade of the coast of Albania by the Turkish Government – Embarrassments of a traveller – Asiatic cholera.

Having so far withdrawn the veil that shrouded the political state of Albania, and recorded the most striking event of its contemporary history; sketched the character of the people, their nationality, passions, tendencies and creeds, with many of their customs and manners, we will resume our descriptions of the country, and continue our travels.