| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

Johann Georg von Hahn

1854

Johann Georg von Hahn:

Travels in Central AlbaniaGerman scholar and father of Albanian studies, Johann Georg von Hahn (1811-1869) was born in Frankfurt am Main and studied law in Giessen and Heidelberg. From 1834 to 1843, he worked for the legal authorities of the newly founded Kingdom of Greece. From 1844 to 1847, he represented the Prussian consulate in Athens, and then transferred to the Austrian vice-consulate in Janina where he came into contact with the Albanians and began learning Albanian. Finally, in 1851, he was appointed Austrian consul on the island of Syros. It was during his years in Janina that Hahn toured Albania and gathered information on Albanian history, philology and folklore. This vast amount of material was published in the seminal three-part “Albanesische Studien” (Albanian Studies), Jena 1854, which laid the foundations for multidisciplinary Albanian studies. He is also remembered for his “Griechische und albanesische Märchen” (Greek and Albanian Folk Tales), Leipzig 1864, and for accounts of his travels in the Balkans “Reise von Belgrad nach Salonik” (Journey from Belgrade to Salonica), Vienna 1861, and “Reise durch die Gebiete des Drin und Vardar” (Journey through the Region of the Drin and Vardar), Vienna 1867, 1869. The following text, taken from “Albanesische Studien,” is the account of von Hahn’s expedition through central Albania in 1850.

Musakja [Myzeqeja]. The coastal plain beginning near Vlora consists initially of a narrow strip of land skirted by hills. The hills disappear after about two hours, though the area, through which the road to Apollonia leads, does not yet become a real plain, because this latter settlement was built on a 200-foot-high hill.

It is only north of the village of Pójanni [Pojan] that one reaches the broad plain of alluvial soil that penetrates deep into the interior. Very little of it is cultivated. It serves as winter pastureland for northern Epirus and Grammos. In the summer it is therefore depopulated and consists of abandoned Vlach villages, without a soul in them, making a curious and by no means welcoming impression. There is nothing to be stolen from these thatched cottages and any damage to them is repaired in the autumn.

The buildings in the farming villages along the road are curious, I would almost say reminiscent of the tropics. The expansive yards are surrounded by hedges of live reeds and contain three, four or more little houses, one of which is used as a home and the others as stables and for equipment. The frames of the houses are made of wood and the roofs are of reeds. The walls are also of reeds, isolated at the most with a thin layer of mud or cow dung. Only the narrow wall in front of the fire is made of clay bricks. As in the homes of Greek peasants, the fire itself burns three to four feet away from the middle of the wall, on which various household utensils hang: jugs, pots, etc. Along this wall runs a two-foot-high and two-foot-wide clay bench. The floor is made of clay, too. There is no hearth, no table, no chair nor stool. Bedding for the night is rolled up in the morning and stored against the wall. Lighting and ventilation are provided by the two doors in the middle of the long sides of the house. The main door is shut at night. The houses are about 20-25 feet in length, 12-15 feet in width. The living and sleeping room, where the fire burns, makes up only half of the space. The other half is for storage. The furnishings are very much as in Greece, including huge round wicker baskets with a clay lid that are used for storing grain. What are particular to the country are the two-wheeled carts that are very common all along the coast. Travellers hate them because of the screech of their hubs and axles that rarely enjoy a spot of grease, not only since they are an insult to the ears but because they awaken visions of thirst. Should the traveller be suffering from fever and not be drinking liquids to try to postpone an oncoming attack, he will most certainly spur on his horse at the very sight of these carts to get away from the screech as quickly as possible. The dry grey mud covering the oxen pulling the carts does nothing to help conjure visions of Illyrian chariots, although it does protect the animals from the countless flies that accompany them on their slow migrations. Not to mention the dust that these ancient animals stir up as much as they can. In short, encountering these oxcarts is one of the most unpleasant things this author has ever experienced. And he was vociferous enough to stop them in their tracks whenever he could not get past them quickly.

Alongside the road run hedges behind which elm trees loom. Up these trees grow grapevines that form festoons as they drape gracefully from tree to tree. The reader will understand what a southern Illyrian landscape looks like if he thinks of the thickets of Lombardy.

There are numerous gypsies in Myzeqeja who are considered slaves of the Sultan. Their services are leased out annually like other State assets (for about 5 purses). They serve as couriers, help bring in the harvest, thresh and shell the maize, etc. Many redeem themselves by paying off the tenant farmers. They also pay 60 piastres per tent and every man who has come of age pays six piastres of head money (harach). Very few of them work as blacksmiths. Most of them make a living selling and taming horses, but yet lead an unsettled life, not without some horse-rustling, it is said.

Horse breeding was common in Myzeqeja in the old days and horses from this region were known throughout the peninsula, though they did not constitute a race of their own. The breeding has declined substantially and I did not notice any horses worth mentioning during my time in Albania.

Were the plains of southern Illyria healthier, they would be among the most blessed regions of the planet. But that the inhabitants face other illnesses than those caused by the bad air, can be seen in the following information received from a reliable source. When the current prelate assumed his post, the registry of the Greek diocese of Berat (officially known as Belgrade, Canina and Spathia) noted the presence of 4,000 Christian homes. Within the space of less than one and a half generations, hardly 2,000 have remained. This decline refers in particular to Myzeqeja. The region has not suffered much from war and uprisings, but the pressure exerted earlier upon the Christian population is said to have been insufferable. Times have fortunately changed and it is to be hoped that, protected by the Tanzimat, the population will increase again. The reason for the decline is not so much apostasy but emigration. That is what people say anyway. But if one looks around at the decrepit appearance and feverish bellies of the babies, one wonders if the ailing mothers are able to bear children who will survive, and it becomes apparent that the main reason for the decline in population is the bad climate. A rapid recovery is unlikely.

Durazzo [Durrës]. Cape Pali may be seen at the northern end of the chain of hills that stretch eight miles in a north-south direction and descend to the coast. The southern end is Durrës.

This chain of hills begins about four miles from the coastline and appears to have been an island in ancient times and later, with alluvial soil, to have transformed itself into a peninsula. The sandy plain that connects it to the interior is only slightly above sea level. It is so low near these hills that the rain that collects and the saltwater that penetrates the area during storms cannot run off. As a result, a series of lagoons has been formed. They are virtually dry in the summer and fill the town and surrounding region with feverish vapours that take on a highly destructive character in late summer.

It is said here that in former times, there was a deep channel, navigable for galleys, that linked the two bays formed by the hills.

The southern bay is named after the town of Durrës. It stretches four miles southwards in a broad crescent towards Cape Laghi and its northern end is the town harbour. Although it is completely open to the south, the ships do not regard it as dangerous when southern winds blow. They claim that the thrust of the waves is forced into a circle by the form of the bay and that the returning waves neutralize the effect of the incoming ones. The seamen complain rather about the unsafe seafloor which is constantly damaged because the ships throw their ballast overboard where they anchor. They attribute bad anchorage, at least in part, to the fact that in February 1846, of twenty ships in the bay, sixteen were hurled onto the beach during a terrible hurricane. All of these ships, some of which having cast three anchors, were so deeply embedded in the sand that only two of them could be put afloat, and this, with unimaginable effort. One can still see some of the hulks of the other ones.

Although nothing has been undertaken to improve navigation here – there isn’t even any harbour police - every departing ship has to pay a port charge of one dollar, not to the imperial treasury but to a company that has taken over customs.

The present town has the form of a small triangle running up the hill and is surrounded by high walls. The market street stretches from the sea gate at the harbour to the land gate. All the other streets are narrow, crooked and dirty. Nowhere is there an open space to get a breath of fresh air once the city gates are closed in the evening. Including the suburb just outside the land gate, the town has a mere 200 houses and a population of 1,000.

It was here that I first saw Barbary doves (Alb. kumrí, in Berat dudí), a bird native to the towns and villages of central Albania. It usually nests in the trees, but only near people’s homes. It is very popular and is considered a good omen. When it coos on the roof of a house, this portends that a family member will be returning from abroad. Its cooing is actually not as melodious as its German sister, but more strident, and the first time I heard it, I thought a bird had been attacked and was enraged. The cooing of the grey pigeon, on the other hand, is more usual and pleasing.

Durrës owes its doves to the endeavours of the Nestor of the Austro-Hungarian consuls, Mr G. Tedeschini, who managed to settle them here after many unsuccessful attempts. I will always be grateful to the hospitality of this venerable gentleman.

We must leave it to future generations to decide on whether the ancient names Epidamnos and Dyrrachium are identical or if they refer to the two distinct halves of the town, Asty and Emporion, and on where the battle took place that brought together Caesar and Pompey in their amazing marches and countermarches. I did not have any luck in finding the Chara root mentioned by the latter, although I suspect that it refers to the Salep root (Orchis mascula v. morio) that is pulverized into flour and imported into Albania from Salonica.

Durrës may be regarded as an outpost of Austrian commerce for its trade routes link it primarily to Trieste and other Austrian ports, whereas the trade routes southwards and to the eastern Italian coastline, and indeed to the ports of northern Albania are insignificant by comparison. The volume of Austrian trade with Durrës under the national flag varies between 900,000 and 1,000,000 guilders, most of which involves exports from Durrës to Austria. Since, however, other flags than the Austrian are involved in this trade, although to a lesser extent, the total volume probably surpasses an average of one million guilders.

Movements of Austrian and foreign merchant vessels operating in Durrës are, with a few exceptions, restricted to trips to and from Austrian ports, and there are a number of ships that, year for year, also serve as postal vessels only on this line. The most common flag in this harbour is the Austrian. […]

Exports from Durrës consist primarily of the following items:

1. Leeches, to Trieste, 400 to 500 vats at 2.5 oka in the winter and 2 oka in the summer. This article is in rapid decline here as elsewhere. Ten years ago, exports were six-times what they are now.

2. Cereals: (a) maize, 40,000 to 50,000 staja to Trieste, Bocca di Cattaro and the smaller Dalmatian ports, very little to the Ionian isles, (b) oats, 15,000 to 20,000 staja, and (c) flaxseed, 4,000 to 5,000 staja to Trieste, as well as small quantities of rye, barley, beans and millet.

3. Hides and leather, to Trieste and Venice: (a) lambskins, 20,000 to 25,000 pieces; (b) kidskins, 3 bales; (c) calfskins, 20 bales, as well as ox skins; exports have only been significant over the last two years because of cattle plague; (d) sheep and goat skins (Cordovani), 80 bales.

4. Wood: (a) timber for ship construction. There was formerly much export to Egypt, Malta and Tunisia, but this has decreased because the forests have been cut down and markets have slumped. For the last two years, 20,000 trunks of oak have been lying along the coast from Durrës to Ishëm, waiting for better prices; (b) barrel staves, 150,000 pieces to Patras for Corinthian barrels; (c) firewood, to Malta.

5. Olive oil, to Trieste. This is the main export article with an average harvest yield of 15,000 ornen. This does not account for the total harvest because, in addition to local consumption, large quantities go inland to central Roumelia and Serbia. Peqin, Kavaja, Tirana and Elbasan are the districts of Albania richest in oil. Exports from here, as from Vlora, Ulqin and Bar, all go to Austria.

6. Tobacco, to Venice. Around Durrës a type of tobacco is grown that is very good for the manufacture of snuff. The Austro-Hungarian board buys 3,000 to 5,000 bales of 50 to 52 oka for the factories in Venice and Milan, according to need, that are checked and moistened here and shipped in this state. The leaves ferment on board, for 40 days from the moment they are loaded. This fermentation produces so much heat on the ships that the sailors have to sleep on deck, even though the tobacco is usually shipped in December and January, and the rising vapours keep everything on board damp. The same ships are usually used for transport because the loading and handling of tobacco requires special care during the fermentation period.

7. Wool, to Venice and Trieste: (a) twice shorn (lana angellina), 20,0000 to 25,000 oka; it comes from Dibra; (b) washed wool, 20,000 oka; (c) unwashed wool, 10,000 to 12,000 oka; (d) glover’s wool (lana calcinata). Finally, 40,000 to 50,000 turtles are exported from here to Fiume [Rijeka] and Trieste and about 1,000 buffalo horns to Venice and Trieste.

Kawaja [Kavaja]. The basin of Kavaja, called after its main settlement, is about one to one and a half hours wide and five hours long. On its west side, it ends at the bay of Durrës and merges with the plain of the Shkumbin to the east. There is not much elevation between the two. Through the basin flow two streams, the Leshnika, that is half an hour south of Kavaja and has water in the summer, too, and the larger Darç, that flows right beside Kavaja. The two streams flow separately into the sea between the saltworks. I have no clear information about the precise course of these streams.

The town itself is situated at the northern edge of the basin, scattered over a wide area, about one and a half hours from the beach. It has 1,000 Muslim and 150 Christian homes (mostly Orthodox Vlachs). The latter have a church about an hour from the town. There are two church ruins in the town itself, but permission to excavate here has always been denied. In general, the influence of the Tanzimat does not seem to have penetrated here as in Epirus because the Christian members of the provincial council (medjlis) have not been allowed to attend sessions.

What I found remarkable is the assertion that the town gets all its imported produce from Durrës, but gets its manufactured, European goods, such as textiles, fezzes, mostly from Monastir [Bitola] and Constantinople. Two trading families from Kavaja maintain branch offices in the latter city.

The Lake of Terbuff [Tërbuf]. Looking southwards about half way between Kavaja and Peqin, I saw a substantial body of water at a distance of about three hours. It appeared as if it was only part of something bigger as hills hid what remained. It cannot be the lake of dunes between the estuaries of the Seman and Shkumbin rivers that is marked Trebuchi on our maps and that the natives named after the nearby village of Karavasta, because it was too far inland. I made several inquiries and learned the following. The lake is called Tërbuf and is situated two hours southsouthwest of Peqin, i.e. on the other side of the Shkumbin, and three hours east of the sea, with which it has no connection, in a longish valley of about three-quarters of an hour in width. It is half an hour wide and four hours long, and has a circumference of nine hours. It is marshy with reedy banks and up to seven fathoms deep in some places. It once supplied 200-300 oka of leeches a month, but now less than ten. There is a particular type of fish that is caught there, called pendëkuqë [red-finned carp], but it is difficult to digest and tastes marshy. Fishing here is a privilege of the Tekke of Skopje, called Pasha Sinanit. The lake does not flow into the sea and is situated two hours from the Lake of Karavasta that is linked to the sea and is much larger. The air around the Lake of Tërbuf is very unhealthy. Because of my weakened feverish condition, I withstood the temptation to verify this information, though I have no doubt as to its accuracy because it stems from several people who either catch leeches there or have spent time there fishing. The lake is not on our maps. Vaudencour’s sketch makes it difficult to ascertain whether he means this lake or the Lake of Karavasta.

In this connection I learnt that the village of Remas, three full hours north of the Seman (a dreadfully swampy place I passed through earlier), is said to be located in the bed of the river of which the marshes are all that remains. The Lake of Tërbuf is three full hours to the east of this.

Pekin [Peqin]. The location of this town is given wrongly on all of our maps because it is not on the southern, but on the northern bank of the Shkumbin. It is not two but five hours from the sea, and not twelve, but seven hours from Elbasan. It is thus not south but southeast of Kavaja, which is five hours away. And finally, the road from Vlora to Durrës does not run through Peqin. It passes rather across the Shkumbin river near its estuary at the village of Bashtova, the archaeological remains of which will be referred to below. However, the road from Durrës to Elbasan, the Via Egnatia, does pass through Peqin. This became particularly apparent to me when I asked around and was always told that there was no other road from Kavaja to Elbasan but the one through Peqin. Peqin may thus be the first station of the Via Egnatia, Clodiana. But this is only a hypothesis because our maps are unreliable and the Peutinger Tables contain many orthographic errors. The countryside around Peqin is hilly all the way up the Shkumbin valley to where the valley ends at Elbasan. The road runs along the north bank of the river and for much of the way, it skirts along the slopes descending to the river, yet when I used it, it was passable and well maintained.

Mosque and clock tower of Peqin

(Photo: Robert Elsie, March 1997)

A quarter of an hour from Peqin, I came upon a channel with seven watermills that irrigated the surrounding fields. The father of the ruling bey had it dug by the mostly Muslim farmers of the area about twenty years ago in unpaid labour, something quite remarkable that shows just how passive the local population is. The seven watermills are leased out on a yearly basis for 90,000 piastres (about 9,000 guilders CM). The town has 90 houses in scattered groups in the wooded hills, and several distant hamlets that are considered part of the town. The centre of town has a pleasant market square adorned with an elegant mosque and a clock tower. Nearby is the wooden manor of the ruling family that has been governing the region since ancient times and constitutes a rare leftover of the Albanian feudal age. Its unwavering loyalty to the sultan has enabled it to retain its old privileges whereas most of the noble families of the region, including the last hereditary Pasha of Shkodra, in whose rebellion they took part, were deposed and banished.

The air is unhealthy, which is said to come from the many rice plantations around the town that produce about 15,000 oka of rice. Judging from the surroundings, I suspect there must be much olive oil, too.

Elbasan. Elbasan is one of those inaccessible cities that have become rarer and rarer in Europe because of the railway. You see the city clearly at the northern end of the valley the moment you enter it. The pure southern evening breezes bring its slender minarets so close that you can hardly believe the distance is a two full hours, as estimated by the guides. Yet that is how far away it is. Of the boring journey towards it, suffice it to be said that the plain is badly cultivated and the river seems to wind its way invisibly out of the mountains at the head of the valley. Along the road not far from the town, there are large groves of willow trees that the unskilled eye might take for olive trees.

Elbasan has 2,000 Muslim and 200 Orthodox and Catholic houses. Of the latter, the 80 Albanian-speaking homes are in the fortress around their metropolitan church and the remaining, Vlach-speaking homes are in the suburbs. There are also many gypsies in town, who, as elsewhere, declare themselves to be Muslims and work as blacksmiths.

There is much trade in the town and its bazaar is quite large, although it does not appear to be different from other bazaars in the country. It has narrow allies covered in boarding or canvas that extend between low, plain-looking stalls with shelves. Wherever there is room, one finds items being sold on the cobblestones, too, and on market days crowds in colourful costumes swarm through the narrow lanes, though they are well-behaved and hardly make any noise. The wider streets have a two-to-four-foot-wide rivulet flowing through them. These streets also serve as passages for the animals. On both sides there are half-foot-high sidewalks for pedestrians.

Elbasan’s most important trade ties are with Trieste and three commercial families of Elbasan have branch offices there. Imported products, Russian and Austrian iron and some manufactured goods arrive via Durrës, but most of the latter, in particular English goods and some German ones are imported from Monastir. But Corfu is now beginning to export English manufactured goods to Albania via Vlora. There is not much trade with Salonica and Constantinople, and hardly any with nearby Berat.

That the Tanzimat has not yet taken effect here can be seen in the fact that local custom still forbids Christian traders from owning stalls in the market. In 1832, the Sadrazam, having suppressed the recent revolt of the hereditary Pasha of Shkodra, passed through here on his journey through Albania and, having torn down the walls of the fortress, issued the Christians a bujurdi [written order] giving them certain freedoms including the freedom to trade in the bazaar. The Christians had these rights confirmed in an imperial firman that, in accordance with local custom, was read out ceremoniously at the courthouse to make its contents known. Following this, five Christian merchants and a poor tobacco cutter called Thomas ventured to set up shop in the bazaar. Everything went well for a time, but when news reached the town that the Sadrazam had been defeated and made prisoner by Mehmet Ali near Kutaya and that Shkodra had risen in revolt against Hafiz Pasha, the merchants were called to the bey one evening, whose extensive palace is situated in the fortress and who served as protector of the nearby Christian neighbourhood, and were warned to close their shops in the bazaar overnight because they were to be plundered by the Muslims. The poor people heeded the warning and acted accordingly as swiftly as possible.

The next morning the Muslim population assembled to take counsel and consider what to do under the circumstances. The four leading families, around whom the population gathered, were so disunited that the town was divided into four parts and, little wonder, conflict soon broke out. In the dispute, one of the chiefs forgot himself and hit another nobleman with his pipe. All jumped to their feet and drew their weapons. Shots could easily have fallen and they would certainly have exterminated one another. But, peacemakers intervened and nothing happened. However, in view of what had occurred, no decision was taken at the assembly.

A few days later, they decided to expel the governor appointed by the Pasha of Shkodra and did so with such resolve that his wife, in the throes of childbirth, was sent packing on her horse, too. She gave birth one hour later outside of town.

All during these events, the poor tobacco cutter Thomas, unwarned, had continued selling his tobacco in the bazaar. The Muslims took their revenge upon him. The newly appointed police chief (kapi buyuk bashi) appeared before his stall with his men and hanged the poor fellow on the spot, and was never called to account for his deed. The other five merchants managed to flee and, once the storm had died down, were given a fine of 11,000 piastres each. They then began to conduct their businesses from their homes and set up shops in them where their wives and daughters traded with the Muslim women who were not allowed to go to the bazaar. They had many customers because they were cheaper than the Muslims. This, of course, caused bad feelings among the Muslim merchants who tried to persuade the Christians to return and open their shops in the bazaar, giving them written assurance of security and protection from the governor. But they always replied by mentioning the name of Thomas.

Bridge of Kurt Pasha,

now destroyed Less than five minutes from the southeast end of town, there is a stone bridge across the Shkumbin. Elbasan is located too far from the river on most of our maps. The bridge was built by the well-known Kurt Pasha of Berat, who played a role in the younger years of Ali of Tepelena. It has eight large arches and a couple of small ones in the bushes on both sides of the river. The principal concern of Turkish, and perhaps Byzantine bridge-builders was to put as little pressure as possible on the arches and to alleviate side pressure on the pillars. The keystones in the archways often serve as the pavement or at least are directly under the pavement and the archways fall steeply to both sides, with the pavement rising again towards the next arch. To know how many arches a Turkish bridge has, the traveller has only to count the hills he crosses. The pillars are penetrated by niches, by one large and long one and two smaller ones on the sides, that often give such bridges a certain grace. But that is not how the Bridge of Elbasan appeared to me. The stone bridge of the Kir river near Shkodra is a fine example. I know of nothing built of stone comparable to the simplicity and grace of that bridge. It looks like a breath of the Divine. I must admit that I saw it during a wonderful sunset. One-arched Turkish bridges over little rivers are usually too high, daring and flimsy to be truly attractive. There are such bridges, five to six metres in width, that are 40, 50 or more feet above the water and without railings. Only those not susceptible to dizziness can ride over them without dismounting.On the way to the bridge, I passed a rectangular square surrounded by a five-foot wall and planted with ancient cypress trees. This is where all the Muslim inhabitants celebrate Great and Little Bayram. No mosque in town would be big enough to hold the religious ceremonies that take place during such feast days. A number of old mullahs in white beards sat smoking in a circle. In the background was a mosque – a truly enchanting vision of the Orient, rare for Albania.

Prayer grounds (namazgjah)

of Elbasan in the 1920s If one looks eastwards from the Bridge of Kurt Pasha, one can enjoy an amazing view of chains of mountains stretching in a north-south direction, the farthest towering above the nearer ranges and separated from them by the river. Behind the town is a ridge of hills called Mali i Krashtës, Cradle Mountain. To the right behind it is Mali i Shushicës, behind that Mali i Polisit, and in the distance is Mali i Mbelishtës. To the left is Mali i Gibaleshit and behind it is Mali i Çermenikës. This mountain region forms the western edge of ancient Candavia, through which the Roman Via Egnatia passes.As mentioned above, the fortress, surrounded by moats, was torn down by the Sadrazam and it is nothing particular to look at. Nowhere on its walls could I find traces of cyclopean stones or ancient ruins. Neither its plan nor its location on the flat land, when there are suitable hills in the vicinity, speak for its antiquity. No one knew anything about ancient walls in the hills.

Yet the distance between the modern town and ancient Scampis noted on the above-mentioned Peutinger Tables cannot have been very great. I believe, as Leake does, that the same holds true of mediaeval Albanon which held the mountain passes leading from the area around Lake Ohrid to the coastal plain, and Farlati informs us that Elbasan was the seat of the Bishop of Albanon.

As to ancient Albanopolis mentioned by Ptolemy, the capital of the Albanian tribes, I cannot concur that it is the same as Scampis, as the geographer asserts, because he gives the two in different locations.

In the first section of this book, I referred in general to the progress that Islam had made in Albania in recent times to the detriment of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. There is much proof of this in the region of Elbasan.

To the east and north of the town is the well-populated, hilly region of Çermenika that has only free villages, i.e. no çifliks. It used to be entirely Catholic. In this region is the beautiful village of Polis, rich in animals, four hours to the east of the town, near the Bridge of Hadji Beqari over the Shkumbin on the main road to Ohrid. It has 60 houses. This village is said to have been visited by Catholic missionaries 25 years ago and to have constructed a mosque 20 years ago. The reason here was not so much external pressure, but the need to belong to some religion.

In Mollagjesh, four hours north of Elbasan, there are apparently still old women to be found who were christened as Catholics. In earlier times, the farm women in the region used to bring their babies into town to have them christened as Orthodox, but the Orthodox Church refused out of fear of the Muslims.

Everyone from Polis to Mollagjesh and Bixëlleja, two hours from Elbasan, used to be Catholic. Place names like Shë’ Mëri (Saint Mary), Shë’ Mëhill (Saint Michael), Shën Jerk (Saint George), Shë’ Nicola (Saint Nicholas), etc. have survived here and in the neighbouring districts despite the conversion of the inhabitants.

To the present day, Martanesh near Mollagjesh still has a large church bell. It is now used to call the inhabitants to assemblies. When the clock tower of Elbasan burned down and the bell melted at the time of the death of Sultan Mehmed, the townspeople wanted to purchase the Martanesh bell. This was, however, refused and they had to get a new bell from Trieste.

Mamli was also Catholic. Several families from this settlement moved to Elbasan 150 years ago and converted to Orthodoxy. The last two villages here belong to the district of Tirana. Judging from the many saints’ names in the villages of the upper Erzen river, where Muslims now live, the situation was probably the same. There are many ruins of Catholic churches here, too.

All the mountain villages around Elbasan suffer from emigration. The emigrants are all Muslims and they leave to work as gardeners and construction workers in Constantinople where they remain for two to five years and make an annual 1000 to 1500 piastres. They travel overland and the journey lasts twenty days. Expenses for food and accommodation amount to 150 to 200 piastres. Two to three caravans set off between the two cities every year.

The district of Elbasan is rich in olive oil. The oil is transported to Monastir and goes from there to Belgrade. Rice production hardly meets local needs. Some of it is exported to Berat, nothing to Monastir.

Two and a half hours southwest of Elbasan there are some sulphur hot springs, the water of which smells like rotten eggs. At one site, called Llixha e Kodrës së Bujarës, Spring of the Hill of the Noblewoman, there are 14 such springs. The most distant ones are less than a quarter of an hour from one another and the springs are as wide as a man’s arm. At another nearby site, Llixha e Idrait or Hidrit or Hidrahut, there are four springs, but they are farther apart than the above-mentioned ones. The smaller springs do not gush all the time, only now and then. The water flows up through the holes in the rocks and rarely reaches the surface. Here, the children sing thrice:

Xhik Papaz! As na bën një herë me gaz?

Papa Xhik, won’t you make us smile?Then the water begins to gush and the children giggle.

The people of Elbasan, as Ghegs, make fun of the Tosks. I heard them say the following of them. Three soldiers-of-fortune from Labëria, all old friends, returned home. The first one wore a beautiful ring on his little finger. The second one had a new crimson jacket, and the third one had a pair of new silken sandals. At the place where they met, there was the corpse of a dead dog. The first man pointed to the dog with his finger with the shining ring on it and asked: “Who killed the dog?” “I am the one with my mighty chest,” replied the second, and beat with his fists upon his new jacket. The third man then stretched his foot out and said: “Well, take it away then, and throw it into a ditch!”

The Monastery of Saint John’s is one hour northwest of Elbasan in the fair valley of the Kuça [Kusha], and is the most notable Orthodox monastery in the country because of the body of Saint John Vladimir that is preserved here. It is not devoid of historical interest because it is perhaps the only building in central Albania left over from the time of the old Bulgarian Empire, destroyed by the Emperor Basil. For this reason, we shall provide here an extract from the legend of this Orthodox saint, as given in his acolouthia printed several times in Venice.

Procession at Saint John’s

(Photo: Hugo Bernatzik 1930)Saint John (Albanian Gjon) was the son of Neman and the grandson of Simon, King of the Bulgarians, who resided in Ohrid. He was born of his mother Anna, a Greek woman of royal blood, in the Serbian town of Vladimir after which he was named, and lived around the year 1000. He was a very pious man from an early age and lived with his wife, a sister of the Bulgarian King Samuil, in a celibate marriage. He once went hunting in the area that was a wilderness at the time, and glimpsed a white hawk bearing a cross. He followed it until the bird dropped the cross on the ground. This happened at the site where the altar of the monastery church now stands. Here he built a church and prayed in it seven times a day. He was interrupted in his pious endeavours by the invasion of the Emperor Basil. He put himself in charge of the Bulgarian army, defeated the Emperor and returned to his church.

The aesthetic life he led gave rise to suspicion and jealousy on the part of his wife who believed that she had lost his affection to another. She complained to her brother, the king, who, in his anger, attacked his brother-in-law and want to slice him to death with his sword. But the king’s sword was powerless against the body of the saint, and so the latter gave his own sword to the king with which he chopped the saint’s head off. John picked his head up, rode to his beloved church and gave the head to the Lord. The murderer went mad and ate his own flesh. Out of remorse, his sister built the monastery around her husband’s favourite church in which his head was preserved.

At one time, the Franks tried to seize the body and load it onto a mule. On the short way from the monastery to the Shkumbin, the sixteen of them were, however, confounded, so they threw the coffin of the holy man into the river so that the current would carry it down to sea. But, behold, the coffin swam up the Shkumbin against the current, into the Kuça river and back to the monastery, where the inhabitants noticed a light radiating from it at night and placed it back where it had been.

But the body did not remain undefiled because the church was destroyed in an earthquake, though it was reconstructed in 1380 by the Lord of all Albania, Charles Thopia, whose inscriptions claim he was a nephew of the King of France.

This is the legend of the monastery. The Priest of Dioclea has a different version of Vladimir. According to him, Vladimir was not a Bulgarian, but a Serb and so, by contrast, we hereby provide an excerpt of this version of the tale, that is very interesting for this region.

Of the three sons of King Chualimir, the eldest one, Petrislavus, held Zenta, the second son Dragimir held Trebinje and Helma, and the third son Miraslavus held Podgoria (Podgorica?). The last son drowned in Lake Shkodra on a journey to visit his elder brother and left his kingdom to him. Vladimir was the son of Petrislavus. It was during his reign that Samuil, King of the Bulgarians, attacked Dalmatia. Vladimir withdrew with all his people to the mons obliquus (no doubt Montenegro). When Samuil, having demanded his surrender in vain, realized that he could not defeat him here, he left part of his army at the foot of the said mountain and marched on Dulcigno [Ulqin], that he besieged unsuccessfully. In the meantime, the Zhupan of the mons obliquus was negotiating with Samuil for the handing over of the king, and to prevent this, the king decided to submit voluntarily and was taken to Prespa, in the vicinity of Ohrid, where Samuil had his court. Samuil razed the towns of Decaratum and Lausium, advanced with fire and sword to Jadera, and returned through Bosnia and Rascia to his own country.

Cossara, the daughter of Samuil, fell in love with the young prisoner, Her father agreed to the liaison and gave him the whole province of Durrës (totam terram Duracenorum). He then invited Vladimir’s uncle Dragomir to come down from the mountains and resume his rule of Trebinje, which he did.

Shortly thereafter, Samuil died, and his son, Radomir, advanced on Constantinople. The Emperor Basil, however, managed to persuade Radomir’s cousin Vladislas to murder him. Vladislas murdered his cousin while he was out hunting, and took power.

Vladislas then invited Vladimir for a visit. But Cossara who lived in a celibate marriage with Vladimir, persuaded her husband to send her instead of him to her cousin’s court, where she was received with honours. The king repeated his invitation and sent a golden cross to Vladimir as a pledge. Vladimir, however, demanded a wooden cross because it was on such a cross that our Saviour suffered, and this was brought to him on the king’s behalf by two bishops and a hermit.

Vladimir set off for the court and God protected him from ambush by the king while he was on his way. When he reached Prespa, he first went to church to pray, as was his wont. When the king discovered this, he sent soldiers to the church door who beheaded Vladimir the moment he came out. This happened on 22 May. His grave in that church became the site of many miracles and crowds flocked to it. Vladislav then allowed the widow to take the body to Craini [Krajina] where Vladimir’s court had been, and he was reburied there at the Church of Saint Mary’s. The widow took the veil and spent the rest of her life in that church. Vladislas died while besieging Durrës, having been slain at dinner by an angel of the Lord. […]

The monastery, situated near the Krraba Pass, suffered much from Albanian warrior bands over the years and was often plundered – most recently fifteen years ago when the men of Dibra and Mat held it for a longer period of time in their revolt against Qose Pasha, the army commander of Monastir [Bitola]. They even destroyed the stone sarcophagus containing the body and stole the silver jewellery adorning the skull. But they did not damage these things and returned them to the people of Elbasan for a ransom of 700 piastres.

The saint’s body is preserved in stone sarcophagus accessible from all sides, on which the story of his life has been painted. Because the Archbishop of Elbasan was absent, the door was sealed with his seal and that of the two sextons. It is said that the wall of the main gate stems from the building constructed by Charles Thopia, whereas the rest is new. Some of the Byzantine decorations on the walls are not badly done.

Tyranna [Tirana]. The town of Tirana and the valley made a very favourable impression on me. The people who live here are considered the most active and roguish of central Albania. The fields, gardens and orchards are tended properly and the latter two are well-fenced. The people are properly and cleanly dressed, the farm animals well cared for, and in most of the villages, there are two-storey, stone houses, which appear quite clean. Nowhere are there any traces of poverty or misery. I was particularly surprised by the town itself. I was expecting a sombre and dirty nest, but encountered a town extending over the watered plain with its gardens and trees. Closer inspection revealed, to my pleasure, that no one was starving or suffering.

There are two little streams that flow over the cobblestones of all the streets, taking all the refuse with them. The colourfully painted mosques, built in an attractive style and surrounded by poplars and cypresses, and the fine rococo tower with the town clock are surrounded by busy crowds of people swarming through the bazaar on official market days and making their way past the many buffalo carts. These are among the most picturesque views I saw anywhere in Albania. There was nothing unusual in the fact that the women from the surrounding countryside were at market, buying and selling their goods, since this is normal everywhere. But what I had not seen anywhere else were numerous women in Muslim urban dress, with many young faces among them, who were sitting on the steps of the mosque or on walls, selling undergarments and old clothes.

By the way, I noticed few people with blond hair and blue eyes here, whereas such individuals seemed very common in Labëria, Vlora, Tepelena and Gjirokastra. The farther north one travels, the rarer they become. I will refrain from commenting any further on Albanian racial characteristics because there is no country in Europe that offers more diversity of human forms than Albania, from individuals of great beauty to those of extreme ugliness [...]

How large is Tirana? My notebook says: “The town has 2,000 houses, of which 100 are Orthodox (almost all Vlachs), six Catholic and the rest Muslim.” Boué, for his part, in Turquie d’Europe IV, p. 545, states: “Tirana, town with 300 houses, or 2,000-3,000 inhabitants, of whom a good portion are Muslim Ghegs.” Chose and pick. But where, on page 543, he claims there are 8,000 inhabitants in Durrës, with others giving 9,000 to 10,000, my notes give 1,000. I am quite sure that I am right because I spent more time in Durrës, was given the same reply by everyone I asked, and this figure seemed to correspond better to reality.

Old though the placename may be, Tirana is a young town, being according to legend, less than two hundred fifty years old. The following is told about the origins of the town:

Once there was a poor bey called Sulejman who had but one young lad as a servant. This lad dreamed one night that the moon fell from the heavens and landed on his right shoulder, radiating a strong light. When his master heard of the dream, he said to the boy, “You will one day be a great man. Go in God’s name and seek your destiny, because if you stay with me, nothing will become of you.” The lad set off and vanished, for he sent no word of his whereabouts. One day, a Tartar messenger arrived on horseback and summoned the bey to Constantinople to appear before the Grand Vizier., and the bey of course obeyed the order. When he was received by the Grand Vizier, it turned out that the latter was his former servant. The vizier entertained the bey lavishly and told him he could wish for whatever he wanted. The bey asked for command over the Sandjak of Ohrid. And so it was. Having taken up his new position, the bey went on a hunting expedition and found himself one day in Tirana, which at the time was a village of 15 houses and a couple of watermills. He was so taken by the location that he built the old mosque in the bazaar. When he set off to war against the Persians and feared he might perish, he gave orders that his body be embalmed and buried in the mosque. And so it happened. 240 years have passed since the death of Sulejman Pasha. The dynasty only died out recently and has been carried on through female lineage to the present Bey of Tirana.

The last descendent, Hadji Et’hem Bey suffered a curious fate. He was driven from Tirana by the Bey of Kroja [Kruja], his traditional foe, and wandered for years as a dervish in Asia. With the help of the last hereditary Pasha of Shkodra, Mustafa Pasha, he regained his inheritance, but after the fall of Mustafa Pasha, he was deposed by the Sadrazam, and Tirana was transferred to the rule of his traditional foes in Kruja, who still own it. Et’hem Bey fled to Elbasan, made peace with his foes and married the daughter of that family.

The following legend is recorded of the traditional enmity between Tirana and Kruja. Despite the hostile relations between the two towns, traders from Kruja managed to steal their way into Tirana market. To recognize them, guards were placed at the gates of the town who pointed to a wooden beam and asked those arriving what it was called. Those who called it trani were recognised as being from Kruja, and beaten up, because the people of Tirana pronounce the word trau.

Migrant workers are nothing unusual in the region of Tirana. The inhabitants of the mountain villages go to Constantinople to work as miners. And in the town, it is still custom for the men to go to Egypt as mercenaries. Most of the food reaches the town on beasts of burden. The horse-drivers of Tirana are famous in all of European Turkey.

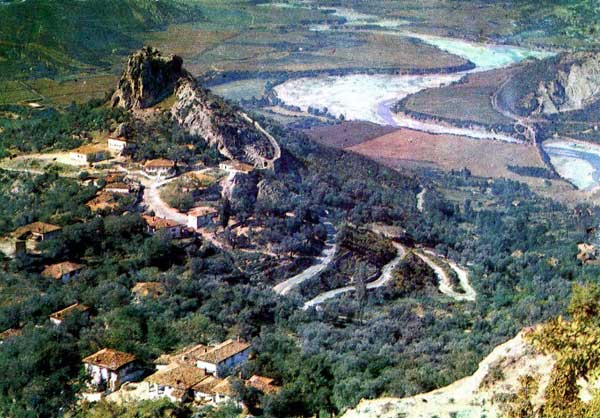

Pertréila [Petrela]. This is the Albanian name for the mountain fortress that is known in history as Scanderbeg’s Petrela. The traveller coming down from Krraba in the direction of Tirana will have it on his left for several hours. It is situated two full hours southwest of Tirana on an isolated peak in the mountain range stretching from Krraba to Cape Rodoni. This peak, probably over 1,000 feet in height, plunges almost vertically to the southwest and north, and therefore needs artificial fortification only to the east. The above-mentioned river Erzen interrupts the range on the northern side of the peak and flows in an east-west direction. The peak is thus the key to the upper valley that stretches towards it.

The Castle of Petrela, 1991

The peak is crowned with several tower-like constructions that are all in ruins. It conveys the overall impression of a dilapidated mediaeval fortress. The walls do not seem to contain any traces of antiquity and are all built with lime mortar. But the fact that the site was inhabited in ancient times can be seen in the fragments of cyclopean walls near the present settlement, about which we will come to speak. The settlement itself consists of several scattered groups, the individual houses of which are scattered among the olive trees. Despite its elevation, the settlement is rich in olive trees. The main part of the settlement is situated on a little plateau before you climb up to the top of the cliff. It has a little bazaar with a coffeehouse, and near it is the grave of Balambán [Balaban]. He was a courageous, miracle-working man who lost his head in an enemy attack when the Turks besieged Durrës. He, however, picked up his head, rode with it to Petrela and deposited it at the site where his grave is currently situated. This is what they say in Petrela, at any rate. Barletius and Hammer, however, speak differently of Balaban. According to them, he was a local, Albanian-born warlord of the Turks who did battle with Scanderbeg and remained at the siege of Kruja. The reader would thus be forgiven if he were to suspect that the legend of the ride of St John Vladimir had crossed the mountains and been taken up by the Turks.

In the old order of battle of the province, the banners of the various towns were arranged as follows: First came Petrela and then Durrës, third was Derénje [Ndroq], of which we will come to speak, and then Kruja, Tirana, etc.

Kroja [Kruja]. In the range of mountains described above, that forms the eastern edge of the valley of Tirana there is one isolated ridge, that is approximately three-quarters of an hour long and has a small plateau full of game at the top of it.

Along this ridge there is a series of hills with oak trees, low beeches and a few conifers between narrow gorges. In the midst of this range there is a promontory that rises sharply, mostly vertically to the south, east and north. It is only to the west that the slope is more gentle. This promontory bears the fortress of Kruja that has natural defences on three sides and required artificial fortification only on the western side for it to be impregnable in the Middle Ages. This was accomplished with thick walls and several round towers.

The Sadrazem, who played such a major role in Albania’s history, had the parapets pulled down during his travels through the country in 1832 and it is thus in ruins. It contains eighty houses, the more or less dilapidated and neglected facades of which lead one to the supposition that there is little prosperity in the place. Among them rise two mosques, one of which with a minaret, the palace of the present governor of Tirana, who, as mentioned above, comes from Kruja, and the clock tower on the western zenith of the promontory. That area is said to be the place where Scanderbeg’s palace once stood, of which, if my information is correct, no trace remains. Around the fortress lie 700 houses mostly amidst groups of trees. The many olive trees in the surroundings make a particularly sad impression since most of them, with a few exceptions, froze during the last unusually cold winter (1848-1850).

Leading to the fortress is a long, narrow alley lined with rows of shops and mostly covered. This is the bazaar of Kruja. It looks so old that one has the impression it has not changed much since the days of Scanderbeg.

Kruja is the market town for the surrounding area, not only for this side of the mountain but for the other side, too. The road from the region of Mat passes through the town and the Sunday market is well frequented by people coming from there. The bazaar is well stocked and offers an excellent overview of commerce and manufacturing in a provincial Albanian town. The word Kruja, the native name for the town, means ‘spring’ or ‘fountain.’ It is worthy of this name because it has several gushing springs, the strongest of which flows alongside the road.

Unfortunately my stay here was too short to investigate the local legends about Scanderbeg, but memory of him seems to have faded in good measure in this area. His name is still well-known, but the people are no longer able to tell tales about him or other figures. The Albanian songs about him risk being forgotten because when I asked about them, I was told they were no longer sung in the area, but that there were still some old people in Mat who knew some. Since I am not able to provide the reader with any new information about Scanderbeg, I must direct his attention to the works of Barletius and Hammer for the history of him and his legendary military exploits, and limit myself to providing information only upon his misunderstood reputation in the population and on the political situation in the country at the time of his appearance. Since the biographer Barletius is only able to record the name of the hero’s father, who ruled over Kruja and other towns, and since he later notes that the fortress was built by a member (Charles) of the mighty house of Thopia, this should suffice to show that George Castriota stemmed from a small and rather obscure dynasty and that he owed his position as commander of Albanian forces not so much to his ancestry but to his own personality.

Who Scanderbeg’s mighty neighbours were can be seen best in the list of Albanian noble families that took part in the meeting of princes of Lezha, a one-time Venetian fortress, where Scanderbeg was elected as their commander.

Foremost among them was the powerful dynasty of Thopia that seems to have split into two branches, a southern branch led by Arianites Golem, later Scanderbeg’s son-in-law, whose influence extended from the Vjosa to the Golf of Arta, and a northern branch represented by Andrea Thopia and his sons, who apparently ruled from the region of Scuria between Tirana and Durrës, but who also reigned over the Krraba mountains and the plains of Myzeqeja. According to Barletius, their influence extended down to Himara. In addition to these were the lords of Dukagjin, the two brothers Nicholas and Paul, whose rivalry caused Scanderbeg much grief. Then, Luke Zacharias, Lord of Dagna [Deja], a bosom friend of Scanderbeg who was later slain by the Dukagjins, George Stresius, the son of Balsha and of a sister of Scanderbeg, who possessed land between Kruja and Lezha; the lords of Myzeqeja who were particularly close friends of Scanderbeg; Peter Spanós and his four sons; the Lekas, Dusman [Dushman] and other lords and dynasties; and finally, the invincible Slav Stephen Cernovik with his two sons, who held power in the valley of the Moraça and in particular at the fortress of Zhablak [Žabljak] with its outlet to the sea. The coastal towns, including Shkodra, were, however, in the hands of the Venetians, and the war that Scanderbeg waged with them for Dagna after the death of Zacharias shows that it was only the common Turkish threat that kept them together.

One must reckon here with six hours to travel from Tirana to Kruja that, in view of its elevated position, can be seen from all open portions of the road right to Lezha.

Those travelling along this road will see on their left side two noteworthy settlements, both on the other side of the Ishëm river, whose course was described above. They are to be found on the top of a ridge of hills that separate the valley of Tirana from the coastal plain. They are called Preza, with its 300 scattered houses centred around a market with a clock tower visible from the distance, and Ishëm, situated in the same range of hills, but to the west and not, as indicated on most maps, to the east of the river. This settlement also has 300 scattered houses. The scattered layout of the settlements, deriving from a marked inclination towards isolation, is a characteristic that divides the Albanians from the modern Greeks and Vlachs, who usually live in close proximity to one another. The scattered nature of the houses makes it difficult to provide accurate distances between Albanian villages. Ishëm has a small fortress that is situated about ¾ of an hour south of the mouth of the river of the same name and that includes a small scala (wharf) that boats can reach.

No one knew anything about any unearthed ruins in the vicinity of these two settlements, but this should not stop future travellers from visiting them, and one suspects that the sites of the present settlements correspond to the old ones.

On Cape Rodoni, called Músheli by the Albanians after a small village there, there is a Catholic monastery called St Anthony of Padua, but it was abandoned when it became uninhabitable after an earthquake.

The most southerly Catholic parish in the valley is Derven situated to the east of the road. I spent the night there after setting out from Kruja. The parish priest, who also tends to the Catholic community of Tirana consisting of six families, had just returned. When he heard of my intention to visit. He lives in a yard of planted trees fenced in by oak planks. Here, too, was the little church looking more like a shed than a house of God, yet that, together with the priest’s home, was considered one of the best buildings of the area. The bell tower was a wooden construction. Everything was kept clean and made a favourable impression. The next day was a Sunday and the priest said: “You will be alone here in the church because my parishioners are expecting me in Tirana.” “Why don’t you summon them here? You have a bell.” “The governor has forbidden us from ringing the bell, but if you wish, we will ring it.” When he said this, I could see trepidation and hope in his expression. The poor man longed to hear the bell ringing once again, but was aware of the possible consequences. I, of course, did not have the bell rung, and remained there all by myself. This was the first mass I had attended in years, but my thoughts were not so much with the ceremony as with the poor church. For the first time, I was quite overwhelmed by the misery of it all. I had lived for years in places where other churches were in a terrible state without my being particularly affected. People are often more self-centred than they realise.

From the village of Derven, the road leads for four hours through an oak forest interrupted only occasionally by clearings. It is named after the village of Shpërdhet [and is the most important oak forest in all of Albania, stretching north to the Mat and covering not only most of the coastal plain between that river and the Ishëm, but also the valleys and slopes of the mountains to the east. I also passed through parts of intact coniferous trees that all seemed to be of the same age and were standing equidistant to one another as if they had been planted. Everything was so pristine that you would have thought you were in a park.

In some parts, the oak trees were interspersed with beeches. The beech trees here never develop into real trees. Several stocks grow from the same root and some of them reach a certain height. They reminded me of some of the oak groves in northern Euboea where the trees are so dense that no branches can grow and the trunks look more like

hop-poles.What was unusual was the silence in the forest as we passed through. Not a single leaf was rustling, not a dove, blackbird, roller, woodpecker or warbler was to be heard. Our party trod its way over the soft soil in absolute silence, except for the occasional clop of a hoof against the roots. It was August and midday. I will never forget the forest of Shpërdhet as long as I live.

Over the last fifty years, the trees from this forest have been felled for ship construction and other usage. The forest used to supply trunks that were 12-18 inches thick. This quality is gone, but there are still some trees of 8-10 inches in diameter. For the moment (1850), there is little demand for them and tree trunks are piled up along the coast waiting for better days. A speculator in Durrës is said to have 20,000 tree trunks waiting in the estuary of the Ishëm. The proximity of the coast and the ease of transport make such speculation tempting.

In this forest, there is a spring of cold mineral water that is worthy of its name Ujë Qelbetë (Stinky Source) because one can smell the stench of rotten eggs from the water half an hour before one reaches the spring. It gushes profusely and the jet is certainly the size of a large apple. The water tastes like meat stock and is used to irrigate the valley into which it flows. Its milky appearance signifies a strong content of magnesia. The inhabitants bathe in the mud produced by the stream and it is supposed to be very effective for all sorts of skin diseases. Near the spring there is a dilapidated church called Santi Quaranta [Forty Saints] that the Albanians called Katërqind Shelëbumitë (the Four Hundred Redeemed), and they hold a large market here on the feast day of the church.

The Coastal Plain of Schjak [Shijak]: The coastal plain that stretches northwards from the peninsula of Durrës from Cape Rodoni is, calculated at Cape Pali, about five hours long and three to four hours wide. To the east it is separated from the valley of Tirana by the above-mentioned range of hills that come down from the Krraba mountains. Initially it stretches north-south, parallel to the coast, but then turns more westward and stretches into the sea, constituting Cape Rodoni, that the Albanians call Músheli. The coastal plain is very fertile, relatively well populated and well cultivated.

The population is partly Muslim, partly Catholic, but the Catholics form the majority. They are divided into two parishes (Juba and Biza). There are Vlach communities in three villages that, as elsewhere, are of Orthodox faith.

The whole area is named after its marketplace Schjak [Shijak], located three hours northeast of Durrës. The place is surrounded by many villages and consists itself only of market stalls and a mosque. It is used by the inhabitants of the area only on market day (Friday) and is empty for the rest of the week.

About ¾ of an hour south of the settlement of Preza, the above-mentioned chain of hills that separates the coastal plain from the valley of Tirana is interrupted by a fertile cross valley of about ¼ of an hour in width. This valley links the coastal plain to the valley of Tirana providing easy access by carriage from Durrës to Tirana without having to cross any elevated passes.

The direct road from Durrës to Tirana, that takes eight hours, is however situated to the south of this valley and passes through the settlement of Nderénje [Ndroq], pronounced more like Ndronj. It is situated half way on the southern bank of the Erzen river and has a citadel on a high mountain. It is inhabited by Muslims only, who are very given to blood-feuding.

This settlement has the largest orchards of olive trees in the whole region and constitutes the northern border of the district of Peqin, being a narrow strip stretching south to north between the districts of Kavaja and Elbasan.

Five minutes to the east of the town there is the river, along the south bank of which the road winds. There is a 60-80 foot high and 200 paces wide cliff consisting of black earth mixed with stone and scree, through which the road must be dug anew each year because the winter torrents wash it away. This dangerous part is called Karaboja (Black Colour) or Byé.

This appears to be the site where the Emperor Alexius was almost captured by the Normans in his pursuit. The emperor had set up his camp near the church of St Nicholas de Petra on the coast. Robert Guiscard, who held Durrës, won the battle. The emperor fled and the Normans pursued him to this place called mala costa, a steep cliff washed by the waters of the Charsanis (known by the Ghegs as the Erzen). His foes were about to capture him when Alexius spurred his horse on, leapt over the cliff and thus escaped his pursuers and easily reached Ohrid after two days of travel through a trackless countryside. Karaboja is about five hours from the coast.

About half way between Ndroq and Tirana, the road crosses the river on a newly constructed stone bridge, leaves the riverbank and continues in an easterly direction towards Tirana.

In the vicinity, about half an hour south of the road, is the settlement of Arbona [Arbana], an ancient town according to legend, that is inhabited by several old Muslim families who have seen better days.

The Erzen continues through the southern part of the coastal plain and flows into the sea one hour north of Cape Pali.

[from: Johann Georg von Hahn, Albanesische Studien (Jena: Fr. Mauke, 1854), p. 73-91; reprint Athens: Karavias, 1981). Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP