| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

The customs wharf in Durrës.

Postcard, ca. 1914.

1867

Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico:

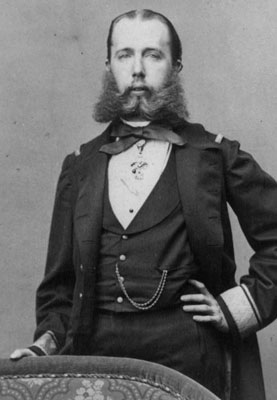

A Visit to AlbaniaFerdinand Maximilian Joseph, Archduke of Austria (1832-1867), was the younger brother of the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph. He was particularly interested in travel. In 1854, at the age of twenty-two, Maximilian was made commander-in-chief of the Austro-Hungarian navy. Ten years later, with French backing, he was proclaimed Emperor of Mexico (1864-1867), but with the rise of republican forces under Benito Juárez, he was arrested and executed.

In his seven-volume German-language writings entitled "From my Life: Travel Sketches, Aphorisms and Poems" (Leipzig 1867), Maximilian published a 170-page account of a trip down the coast of Albania, during which he went hunting in Rodoni. This work includes a curious description of Durrës, languishing under Ottoman rule, that did not impress him at all.

Maximilian I,

Emperor of MexicoWe travelled the whole night and the next day, passing Cape Pali, and on the following afternoon, we sailed past the long sandbank of Santa Lucia stretching out into the sea, which forms a protective barrier for Durrës. We then continued in the direction of the so-called Pietra Bianca [Shkëmbi i Kavajës], a shining cliff in the hills along the coast, and were piloted into the harbour of Durrës. The expansive bay of Durrës is formed by two ranges of hills extending into the sea, the one to the north being wooded as it descends to the plain.

At the foot of these hills lies Durrës, situated between the plain and the cape, right by the harbour. The farthest buildings of the town are up on the slope itself. At the present time, it is a sad hole surrounded by dilapidated walls and parapets. Visible in the little town are one full minaret and another partially damaged one. Further up on the hill there is a collection of ruins of palaces or barracks. One of the two town gates faces the harbour and a customs office, which consists of a wooden hut, of course in ruins, too. Should you wish to approach Durrës from the sea and clamber onto the so-called quai, I would strongly suggest you take out life insurance in London, if the money-making English were willing to ensure travellers to Durrës in the first place. It is a horrifying undertaking to tap one's way along the rickety boards past the swaying piles of the wharf to get to land. Right beside this so-called quai between the sea and the customs office there is a splendid old plane tree, that, like the minaret, is the symbol of every true Ottoman town.

To the right of the town stretches a flat region bordered by hills rising higher and higher. This picturesque chain of hills, rich in cliffs and forests, below which are fields and meadows, forms the horizon to the south as it stretches out into the sea. There, in the azure mist, one can see the tower of Guerrin Meschino, the favourite hero of our sailors, whose adventures are read about on all of our ships. The bay is too large or the town too small to call the whole ensemble charming or interesting, yet it is not devoid of character. The flat region I referred to above is actually a large body of stagnant water which formerly made the cape and the town into an island and allowed Greek and Roman galleys to enter the harbour from the bay behind the town to the north. But now this body of water itself has been interrupted by some sandbanks.

We sent a cadet into the dreary-looking town to inform the consular official of our arrival. He soon returned and put the whole ship into a state of confusion with the report he brought us of his visit to the consulate. It must be remembered that the simple young lad had just been in Rodoni and now reported to us of a spacious salon, a richly decorated divan, opulent oriental apparatus for incense and the charmingly beautiful daughter of the consul decked in gold brocade and diamonds, "a lady of incomparable charm, a rare pearl." After the dreadful impression this little town had made on us, this was like hosanna. We regained courage and were indeed quite excited at the approach of the launch. On it arrived Padre Negri and, in his entourage, was the lucky father of the incomparable maiden as well as his honourable, though now aged uncle, the dean of the consuls, the eighty-six-year-old Tedeschini. The lucky father was also the wealthiest merchant in Durrës, a pleasant, patriarchal fellow who had served in Church and in government and proved to be very supportive of us during our stay, heaping us with kindness. This dean of the consuls, now in retirement, had wits as sharp as vinegar and, over his long years here, had studied and got to know the country, its customs and virtues. He also had a funny vein so that it was informative and pleasant to be in his company. He came on board dressed in consular hunting garments, rather like I imagine a head forester at the theatre. A long black kilt with green and gold hunting lapels hung loosely around his ancient thighs. His bright-looking head, at the back of which one instinctively sought a queue, was covered by an unceremonious hunting cap with a huge visor to protect against sun and rain.

I ventured onto dry land that very evening with the honourable Tedeschini brothers. We had just made our way over the perilous wharf when we were surrounded by swarms of riff-raff. Among them was a sort of fortress commander dressed, with the dignity of a sergeant, in a torn and threadbare uniform, and his staff, who were even more tattered and eager for baksheesh than he was. They were a horde of booze-peddlers, all manner of naked youth, townspeople and peasants, covered in filth and yet with colourful costumes, porters and jet-black gypsies of all ages, clothed in rags, real figures of the underworld.

In the branches of the plane trees, under the golden firmament of foliage of which we advanced to get to the city gate cooed innumerable turtledoves, joyful and exuberating guests that our dean had introduced into Durrës. The dumbfounded fortress guards stood around in the gateway, at the sides of which lay granite columns from the town's past glory. Good God, what characters they were! A handful of raggedy, drunken cripples. We discovered later just how fortified and well-defended the gate was from a conversation with the Consul of Shkodra, who arrived one night and was not let in. He then simply rammed the gate open and gained access to the capital of Albania with no problem at all.

The heart of the town, inside the fortress walls, looks even worse. Endless rows of dilapidated, filthy houses with roofs on the verge of collapse and a stench that made one reel. Such is the poetry of the Orient.

The town looks like the leftover stage props of some Turkish market ballet, abandoned for decades in the basement of a theatre and covered in cobwebs, and then accidentally brought forth, still covered in dust and cobwebs, into the pale footlights. If you add to this description a few retired stand-ins and elderly performers, dressed in costumes from the flee market and reeking of colophony and soot from the extinguished lamps, you can imagine what Durrës looked like. All the cities of the Orient look more or less like this, even Cairo and Smyrna, but the latter are large and full of life and, instead of rags, one finds gold brocade and Indian shawls. Yet nature has added poetry and romance, for a mosque and a minaret, even such small and dilapidated ones as here in Durrës, are visions not to be forgotten, and if the roofs of the bazaar cave in, they are soon covered in vines and golden grapes that, like chains, hold the structures back from total collapse. Though the population is small, one still comes upon colourful old Turkish figures, with huge turbans and long beards who, with pipe and coffee, sit around passively in the stalls of the bazaar and, with Mohammedan fatalism, wait for a buyer without the slightest movement or friendly gesture to encourage the purchase of their wares. The stench that lingers among the houses and palaces and in streets and squares throughout the Orient is more than apparent here… Tripping over piles of dung and garbage, I made my way through to the second gate of Durrës where a couple of yokel guards were supposedly caring for the safety and well-being of the townspeople. Just beyond the gate is an irregular-shaped cemetery in which one could see the bases of ancient columns of granite. Gypsies live in among the gardens here, and at the foot of the seawalls there is a marsh leading out to lagoons, the playground of great white egrets. I went for a brief swim in the twilight and returned to the ship, less than delighted by the wonders of this Oriental metropolis.

[excerpt from: Ein Stück Albanien. in: Aus meinem Leben: Reiseskizzen, Aphorismen, Gedichte von Maximilian, Kaiser von Mexiko (Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot 1867), vol. 4, p. 143-149. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP