| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

Fanny Janet Blunt

1878

Fanny Janet Blunt:

The AlbaniansFanny Janet Blunt (1839-1926) was born in Therapia, a suburb of Constantinople. Her father, Donald Sandison, had gone to Turkey as a representative of the British East India Company and, after the Janissary uprising, became British consul in Bursa. In Monastir (Bitola), she met her future husband, Sir John Elijah Blunt who was British vice-consul in Skopje. They were married in Monastir in 1858 and later settled in Skopje. In 1902, the Blunts took up residence in Malta where she died in 1926. Lady Blunt is remembered for her two-volume study of “The Peoples of Turkey” (London 1878). The chapter on the Albanians, containing many of the standard cliches, provides a nonetheless interesting view of nineteenth-century knowledge about and views of the Albanian people.

A well-armed Muslim from Tuzi

The Albanians, like most of the races of minor importance inhabiting European Turkey, are little known to the civilised world. Albania, with its impassable mountains, broken by deep and precipitous ravines, the footways of torrents, has been visited only “by those few travellers who have had enough courage and adventurous spirit to penetrate into its fastnesses. This country, occupying the place of the ancient Illyria and Epirus, was in the middle ages called Arvanasi, and later on Arnaoutlik by the Turks and Arvanitia by the Greeks; but in the native tongue it is called Skiperi, or “land of rocks.” It is divided into Upper and Lower Albania, and forms two vilayets, that of Scutari (comprising the provinces of Berat, El Bassan, Ochrida, Upper and Lower Dibra, Tirana, Candia, Duratzo, Cruia, Tessi, Scutari, Dulcigno, and Podgoritza), and that of Joannina, in Epirus (comprising Joannina, Konitza, Paleopogoyani, Argyrokastro, Delvino, Parakalanio, Pararnythia, Margariti, Leapourie or Arbar, and Avlona).

Owing to the mountainous character of the country, and the turbulent and warlike disposition of its inhabitants, it is still unexplored in many parts, poorly cultivated in others, and everywhere much neglected in its rich and fertile valleys. Unfortunately agriculture, still in a very primitive and neglected condition throughout Turkey, is especially so in Albania. This neglect, however prejudicial to the well-being of the inhabitants, rather heightens the wild beauty of the scenery, the changing grandeur and loveliness of which alternately awes and delights the traveller.

Shut out from the civilised world by the want of roads and means of communication, all the natural advantages the country possesses have remained stationary, and its beauty and fertility turned to little account by the wild and semi-savage population that inhabits it.

The principal productions of Illyrian Albania are horses, sheep, and oxen, reared in the valleys of the Mousalda; grain is extensively grown at Tirana ; and rye and Indian corn are grown in El Bassan; and in some parts of Dibra a coarse kind of silk is manufactured into home-spun tissues, and used for the elaborate embroidery of the picturesque national costume. A stout felt used for the capa, or cloak, is made of wool. A kind of red leather, and other articles of minor importance, are also manufactured in these parts.

Epirus, or Lower Albania, owing to its more favourable situation and the mildness of its climate, is by far the more fertile and better cultivated of the two vilayets. In addition to the above-mentioned products, it grows rice, cotton, olives, tobacco, oranges, citrons, grapes, and cochineal; Though agriculture is carried on in the same primitive manner, richer harvests are produced, and, as shown by the yearly returns, there is a steady increase of the export trade.

Albania abounds in minerals, but the mines are little known, still less worked. Hot springs, possessing valuable medicinal qualities, are also to be found in many places, but the country people are totally ignorant of their properties, and take the waters indiscriminately for any ailments they may happen to have, and, in obedience to the old superstitious reverence for the spirits of the fountains, even drink from several different sources in the hope of gaining favour with their respective nymphs.

The large landowners, both in Upper and Lower Albania, are Mohammedans, often perverted from Christianity. They still exercise a despotic and unlimited control over the peasants, and show the convert’s proverbial spirit of intolerance towards their brethren who hold fast the faith of their fathers. At the beginning of this century, and before Ali Pasha had made himself the complete master of Joannina, much of the landed property in Lower Albania was held by Christians, and many semi-independent villages, entirely inhabited by Christians, were to be found scattered all over the country. Their number was sadly diminished during the revolutionary convulsion that upset the country. The property of many Christian landholders experienced the same fate. Their estates were snatched from their lawful owners by the wily, avaricious, and hypocritical despot, who, employing by turns the three methods of force, fraud, and nominal compensation, drove away the owners and appropriated the lands to himself. After his death all these lands passed to the crown as Imlak property, and were never restored to their former possessors.

The landed property in both Upper and Lower Albania still retains much of the characteristics of the species of feudal system which once prevailed throughout Turkey; but instead of the rule of a few powerful Beys or one single despot, a legion of petty tyrants hold the people in bondage. Yet there may be found among the landholders a few, poorer than the rest, who are respected for their integrity and for their paternal treatment of the peasants on their estates.

The general aspect of the towns and villages in Upper Albania differs very little from that of other towns and villages in Turkey. The same want of finish and clumsiness of workmanship prevail in all the Albanian houses, which are usually detached from one another and stand in court-yards surrounded by high walls. Some of these dwellings are complete fortresses ; but this is not on account of the terrible never-ending blood-feuds transmitted from generation to generation, which make each man’s life (out-of-doors) the least secure of his possessions. In times of peace his house can be left with open gates, and is held sacred and respected even by the vilest and most desperate characters: for it is a point of honour with an Albanian never to incur the disgrace of shedding a man’s blood in his own house; but the moment he crosses the threshold, he is at the mercy of his foe.

An Albanian chieftain, who had a deadly quarrel with a neighbour and consequently was in terror of his life, was compelled to stay within doors for twelve long years, knowing the risk he ran if the threshold were crossed. Finally, craving a little liberty, he obtained an armistice and was allowed perfect freedom for a short space of time.

In times of open contention the houses are fortified and guarded by armed bands, who conceal themselves in strongholds attached to some of the buildings, watch for the approach of the enemy, and open fire upon them from the loop-holes with which the walls are pierced.

The furniture of their dwelling-houses is scanty, poor, and comfortless. Some valuable carpets, a gorgeously embroidered sofa in the reception-room, and a few indispensable articles, are all they possess. The streets are narrow and badly paved, and look dismal and deserted. The bazars and shops are inferior to those of most of the towns of Turkey. They contain no variety of objects for use or ornament beyond those absolutely necessary for domestic purposes.

The villages are far more curious and interesting to the traveller than the towns. Some of these in Upper Albania, in mountainous districts, are at a great distance from each other, and are perched up on the summits of high rocks that tower above each other in successive ranges, in some places forming a natural and impassable rampart to the village, in others trodden into steep paths where the goat doubtless delights to climb, but where man experiences any but agreeable sensations.

Lower Albania, better known to travellers, is less rugged and wild in appearance. But here and there we meet with mountainous districts—such as the far-famed canton of Souli, which in the time of Ali Pasha numbered eleven villages, some scattered on the peaks of mountains, others studding their skirts; while the terrible Acheron gloomily wound its way through the deep gorges that helped to secure the river its victims.

Souli, defended by its 13,000 inhabitants, withstood the siege of the dreaded pasha’s armies, held them in check for fifteen years, and acquired undying fame in the history of the war of Greek independence for heroism hardly surpassed by the most valiant feats of the ancients, and with which nothing in modern warfare can compare. Every Souliot, man, woman, and child, was ready to perish in the defence. The women and children who had fought so long by the side of their husbands and fathers, at the last extremity, preferring death to captivity and dishonour, threw themselves from the rocks into the dark stream below, while the few that survived the final destruction cut their way through their enemies, and were scattered over Greece to tell the sad tale of the fall of Souli.

The plateau of Joannina is entirely surrounded by wooded mountains, and is from 1,200 to 1,500 feet above the level of the sea. On this table land is a lake about fourteen miles in length and six in breadth, on the rich borders of which rises the town of Joannina, like a fairy palace in an enchanted land. This town, which contains 25,000 inhabitants, became the favourite abode of Ali Pasha, who transformed and embellished it to a considerable extent, and founded schools and libraries.

The edifices erected by him were partly destroyed by his followers, when his power was supposed to have reached its end, together with the gilded kiosks and superb palaces built for his own enjoyment. All that Joannina can boast of at the present day is the exceeding beauty of its situation, and the activity that Greek enterprise has given to its commerce, and the excellent schools and syllogae that have been established and are said to be doing wonders in improving and educating the new generation of Epirus.

The Albanians are divided into several distinct races, each presenting marked features of difference from the other and occupying separate districts. Those of Upper Albania are called Ghegs, and inhabit that portion of the country called Ghegueria, which extends from the frontiers of Bosnia and Montenegro to Berat.

These men are broad-chested, tall, and robust, have regular features, and a proud, manly, independent mien. Their personal attractions are not a little enhanced by their rich and picturesque national costume—a pair of cloth gaiters; an embroidered jacket with open sleeves; a double-breasted waistcoat; the Greek fustanella (white calico kilt), surmounted by a cloth skirt opened in front; a kemer, or leather belt, decorated with silver ornaments, and holding a pistol, yataghan, and other arms of fine workmanship. The whole costume is richly worked with gold thread. On the head is worn a fez, wider at the top than round the head, and ornamented with a long tassel.

Albanian costume

(Joseph Cartwright, 1822)

The Tosks inhabiting Lower Albania, in the sandjaks of Avlona and Berat, and the Tchames and Liaps of the sandjaks of Delvina and Joannina, designate their country Tchamouria and Liapouria. These latter are supposed to be direct descendants of ancient Hellenes, as they speak the Greek language with greater purity than the rest; and certainly some of their characteristic features bear a great resemblance to those of the ancient Greeks. All the Albanians of Epirus use the Greek language, and are more conversant with it than with Turkish, which in some places is not spoken at all.

The Tosks are tall and well built, and extremely agile in all their movements ; their features are regular and intelligent, but like most Albanians they have a fierce, cruel, and sometimes cunning cast of countenance, and a swagger in their gait, by which they can easily be distinguished from the other races, even when divested of their national costume. They are of a warlike and ferocious disposition, yet they have noble qualities which atone in some measure for their ferocity and produce a very mixed impression of the national character. They are a constant source of dread to strangers, but objects of implicit confidence and trust to those who have gained their friendship and earned their gratitude.

In bravery, trustworthiness, and honour, the Ghegs bear the palm. No Gheg will scruple to “take to the road” if he is short of money and has nothing better to do. If any man he may meet on the high road disregards his command, “Des dour” (stand still), he thinks nothing of cutting his throat or settling him with a pistol-shot: but if a Gheg has once tasted your bread and salt or owes you a debt of gratitude or is employed in your service, all his terrible qualities vanish and he becomes the most devoted, attached, and faithful of friends and servants. Generally speaking, the Ghegs are abstemious and not much addicted to the vices of Asiatics. Women are respected by them and seldom exposed to the attacks of brigands or libertines.

These characteristics are so general and so deeply rooted in the character of the Gheg, that consuls, merchants, and others, who need brave and faithful retainers, employ them in preference to men of any other race.

I was once making a journey across country to a watering-place in Albania, and set out for this deserted and isolated spot with a capital escort; accompanied moreover by a wealthy Christian dignitary of the town in which I had been staying. During a short halt we made in a mountain gorge to refresh ourselves with luncheon, near a ruined and deserted bekleme or guard-house, suddenly a fine but savage-looking Albanian appeared before us. He was followed by several other sturdy fellows, all armed to the teeth. My friend turned pale, and the escort, taking to their guns, stood on the defensive.

But the feeling of fear soon vanished from my people, as the Albanians approached them, and instead of uttering the dreaded “Des dour!” gracefully put their hands on their breasts and repeated the much more agreeable welcome word “Merhaba!” The band chatted with my men, whilst their chieftain approached my travelling companion, and entered into conversation with him, every now and then giving a glance at me with an expression of wonder on his face. At last, he inquired who I was, and declared he was astonished at the independent spirit of the Inglis lady, who, in spite of fatigue and danger, had ventured so far.

He willingly accepted our offer of luncheon; first dipping a piece of bread in salt and eating it. My horse was then brought up; the chief stood by and gallantly held the stirrup while I mounted. I thanked him, and we rode off at a gallop. After we had gone some distance on our road, my friend heaved a deep sigh of relief, and said to me, “Do you know who has been lunching with us, holding your stirrup, and assisting you to mount? It is the fiercest and most terrible of Albanian brigand chiefs in this neighbourhood! For the last seven years he and his band have been the terror of this kaza, in consequence of their robberies and murders, respecting none but those of your sex,—guided, I presume, in this, by the superstition, or let us say point of honour, some Albanians strictly observe, that it is cowardly and unlucky to attack women.”

An adventure that lately happened to a friend of mine will show the manner in which Ghegs remember a good service rendered them. Some years ago, a few Albanians, personally known to the gentleman in question, who owns a large estate in Macedonia, heard that three of their fellow-countrymen had got into trouble. Through the influence Mr. A. possessed with the local authorities, their release was obtained. The incident had almost passed out of his memory when it was unexpectedly recalled at a critical moment. Some Albanian beys, who had a spite against Mr. A., in consequence of a disputed portion of land, resolved to take advantage of the present state of anarchy and disorder in the country to have him or his son assassinated the next time either of them should visit the estate. The villainous scheme was entrusted to a band of Albanian brigands that were known to be lurking in the vicinity of Mr. A.’s estate. At harvest time, as he was about to start for the country, he received a crumpled dirty little epistle, written in the Greek-Albanian dialect, to this effect:

“Much esteemed Effendi, and venerated benefactor,

Some years ago, your most humble servant and his companions were in difficulties. You saved them from prison and perhaps from the halter. The service has never been forgotten, and the debt we owe to you will be shortly redeemed by my informing you that the robber band of Albanians in the vicinity of your chiftlik have received instructions and have accepted the task of shooting you down the first time you come in this direction. I and my valiant men will be on the look-out to prevent the event if possible, but we warn you to be on your guard, for your life is in danger.

Kissing your hand respectfully,

I sign myself,

A MEMBER OF THE VERY BAND!”Another friend related to me a strange adventure he had with an Albanian ex-brigand, who for some time had been in his service. This gentleman was a millionaire of the town of P., who in his younger days often collected the tithes of his whole district, and consequently had occasion to travel far into the interior and bring back with him large sums of money. During these tours the faithful Albanian never failed to accompany his master. On one occasion, however, when they had penetrated into the wildest part of his jurisdiction, his servant walked into the room where he was seated, and after making his temenla, or salute, said, “Chorbadji, I shall leave you; therefore I have come to say to you Allah ‘semarladu (good-bye).”

“ Why,” said the astonished gentleman, “what is to become of me in this outlandish place without you?”

“Oh,” was the response, “I leave you because I have consented to attack and rob you, and as such an act would be cowardly and treacherous while I eat your bread and salt. I give you notice that I mean to do it on the highway as you return home, so take what precautions you like, that it may be fair play between us.” This said, he made a second temenla and disappeared.

He was as good as his word; going back to his former profession, he soon found out and joined a band of brigands and at their head waylaid and attacked his former master, who, well aware of the character of the man he had to deal with and the dangers that awaited him, had taken measures accordingly and provided himself with an escort strong enough to overpower the brigands.

The Albanians before the Turkish conquest professed the Christian religion, which, however, does not appear to have been very deeply rooted in the hearts of the people; from time immemorial they were more famous for their warlike propensities and adventurous exploits than for their good principles.

After the conquest, Islam, finding a favourable soil in which to plant itself, made considerable progress in some districts, where the inhabitants willingly adopted it in order to escape persecution and oppression. This progress, however, was not very extensive until the time of the famous Iskander Beg, or Scanderbeg, who played so prominent a rôle in the history of his country, and whose desertion of the Mohammedan and adoption of the Christian religion so exasperated Sultan Murad, that he forthwith ordered that most of the Christian churches should be converted into mosques and that all Epirots should be circumcised under pain of death.

The second impulse Mohammedanism received in Albania was under the rule of Ali Pasha, when whole villages were converted to Islam, though their inhabitants to this day bear Christian names and in some cases the mother or wife is allowed to retain the faith of her fathers and will keep her fasts and feasts and attend her Christian church while her husband joins the Mussulman congregation. In those parts of Epirus, however, where the Greek population was in the majority and its ignorant though devout clergy had influence with the people, they held fast to their religion as they did to their language.

The Mirdites were equally steadfast to their faith and purpose, and have remained among the most faithful and devout followers of the Pope. The number of Roman Catholic Mirdites is reckoned at about 140,000 souls, scattered in the different districts of Albania. They have several bishoprics, and their bishops and priests are sent from Rome or Scutari. The Mirdites make fine soldiers, and have often been engaged by the Porte as contingent troops, or employed in active service. They take readily to commerce and agriculture, and on the whole may be considered the most advanced and civilised of the Illyrian Albanians. They might, however, progress much more rapidly if their pastors, to whose guidance they submit themselves implicitly, would follow the example of the Greeks in Epirus, and introduce a more liberal course of instruction; for the education is at present very limited beyond the religious branches. There can be no doubt that excessive religious teaching among ignorant people, though a powerful preservative of the faith, tends inevitably to render them narrow-minded, bigoted, and incapable of self-development.

The Mohammedanism of the Albanians is not very deeply rooted, nor does it bear the stamp of the true faith. Followers of the Prophet in Lower Albania especially may be heard to swear alternately by the Panaghia (blessed Virgin) and the Prophet, without appearing disposed to follow too closely the doctrines of either the Bible or the Koran. It is an undoubted fact that the Moslems of Albania contrast very unfavourably with the Christians.

The Tosks are held in ill-repute on account of the difficulty they seem to experience in defining the difference between treachery and good faith. They are clever, and have made more progress than the Ghegs in the civilisation that Greece is endeavouring to infuse among her neighbours. Some of their districts are worthy of mention, on account of the taste for learning displayed by their inhabitants, the earnestness with which they receive instruction, and the good results that have already crowned their praiseworthy efforts.

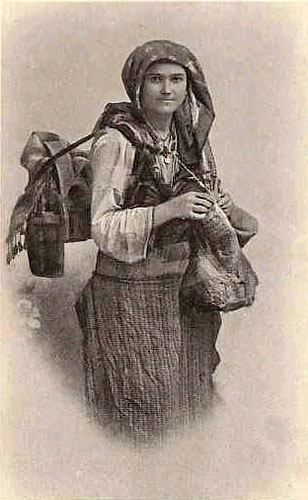

Beggar woman

(Photo: Marubbi 1936)Zagora, for instance, famous as having afforded shelter to many Greeks after the conquest of Constantinople, is renowned for the intelligence and general enlightenment of its inhabitants. The sterile and unproductive soil induces the men to rely less upon the fruits of their manual toil than upon their mental labour, consequently most of them migrate to other countries, seeking their fortune. Some take to commerce, others to professions, and after realising a competence they return to their native land and impart the more advanced ideas their experience has given them to their compatriots who have not enjoyed the same privileges.

The women of Zagora are much esteemed for their virtues and enlightenment. Such facts as these make a refreshing contrast to the dark cloud of ignorance which, in spite of the pure sky of Albania and the beauty of the scenery, still hangs thickly on the land, and casts a shadow where Nature meant all to be sunshine.

The warlike instincts of the Albanian find more scope for action in the Mohammedan than in the Christian religion. They gladly accept an invitation to fight the battles of the Porte or those of any nation that will pay them. This help must, however, be given in the way most agreeable to themselves, i.e. as paid contingents under the command of their own chieftains, to whom they show implicit obedience and fidelity. Under the beloved banner of their Bey, legions will collect, equally ready to do the irregular work of the Bashi-bazouks or to be placed in the regular army.

But, as a rule; the Albanian objects to ordinary conscription, and avoids it, if possible, by a direct refusal to be enrolled, or else makes his escape. When on the road to the seat of war, a regiment of Albanians is a terrible scourge to the country it passes through; like locusts, they leave nothing but naked stalks and barren ground behind them.

The principal merits of the Albanian soldier are his rapidity in motion, steady aim, carelessness of life, and hardy endurance in privation. An Albanian’s gun is his companion and his means of subsistence in peace or war. To it he looks for his daily bread more than to any other source, and he uses it with a skill not easily matched.

When travelling in Upper Albania, we halted one day in a field which appeared quite uncultivated and waste, and were making arrangements for our mid-day meal, when an Albanian bekchi (forest-keeper) appeared on the scene and ordered us to quit the spot, as it was cultivated ground. Our escort remonstrated with the fellow, saying that it was the only convenient place near for a halt, and that now we had alighted we should remain where we were until we had finished our meal.

The Albanian, entirely regardless of the number of the escort and the authority of government servants, became more persistent in his commands, and the guards lost patience and threatened to arrest him and take him before the Mudir of the town that lay a little further on. “The Mudir,” scornfully repeated the mountaineer, “and who told you that I recognise the authority of the Mudir?” Then taking his long gun from his shoulder, he held it up and said, “This is my authority, and no other can influence me or acquire any power over me!”

The social relations of the Albanians are limited to two ideas, vendetta and bessa (peace).

In cases of personal insult or offence the vendetta is settled on the spot. Both parties stand up, the insulted full of indignation and thirsting for revenge, the offender repentant, perhaps, or persistent. The aggrieved person, even in the former case, seldom yields to persuasion or softens into forgiveness; he draws a brace of pistols and presents them to his antagonist to make his choice. The little fingers of their left hands are linked together and they fire simultaneously. A survivor is rare in such cases, and the feud thus caused between the relatives of both parties is perpetuated from generation to generation.

It takes very little to provoke these terrible blood-feuds, and one or two instances that have come under my direct notice will suffice to give an idea of their nature and the violence with which real or fancied insult is avenged.

One happened while I was at Uskup. The cause was nothing more weighty than a contention between two Albanian sportsmen, who were disputing the possession of a hare that each maintained he had shot. The dispute became so violent that a duel was resorted to as the only way to settle it. It came off on the common in the presence of the combatants’ relatives and friends, who joined in the quarrel; and a general battle ensued, in which the women fought side by side with their husbands and brothers. A girl of seventeen, a sister of one of the two sportsmen, fought with the courage of a heroine, and with a success worthy of a better cause. Fourteen victims fell on that day.

The Governor of Uskup, who related the story to me, said that he despaired of ever seeing these savage people yield to the influence of their more refined neighbours, or become entirely submissive to the Sultan’s government. But great changes have taken place since then with respect to their submission to the Porte. The Government is now able almost safely to send governors and sub-governors into Albania to collect taxes from such as choose to pay them, and even draw a certain number of recruits from the most turbulent and independent districts.

Another of these lamentable blood-feuds happened in Upper Dibra, and was witnessed by one of my friends then living there.

It originated in two lads at the village fountain throwing stones and breaking the pitcher of an Albanian girl who had come to fetch water. This was considered an insult to her maidenhood and was at once made the cause of a serious quarrel by the friends of the two parties. A fight ensued in which no less than sixty people lost their lives. Women’s honour is held in such high esteem in these wild regions that so trivial an accident suffices to cause a terrible destruction of life.

Albanian women are generally armed, not for the purpose of self-defence—no Albanian would attack a woman in his own country—but rather that they may be able to join in the brawls of their male relatives, and fight by their side. The respect entertained for women accounts for a strange custom prevalent among Albanians,—that of offering to strangers who wish to traverse their country the escort of a woman. Thus accompanied, the traveller may proceed with safety into the most isolated regions without any chance of harm coming to him.

The Albanian women are lively and of an independent spirit, but utterly unlettered. Very few of the Mohammedans in Lower Albania possess any knowledge of reading or writing. They are, however, proud and dignified, strict observers of the rules of national etiquette; and they attach great importance to the antiquity of their families, and regulate their marriages by the degrees of rank and lineage.

The natural beauty of the Albanian girl soon disappears after she has entered upon the married state. She then begins to dye her hair, to which nature has often given a golden hue, jet black; she besmears her face with a pernicious white composition, blackens her teeth, and reddens her hands with henna; the general effect of the process is to make her ugly during youth, and absolutely hideous in old age. The paint they use is not only most destructive to the complexion, but also to the teeth, which decay rapidly from its use. I believe they blacken their teeth artificially to hide its effects. On my inquiring the reason of this strange custom of some Albanian ladies, they laughed at my disapproval of it, and told me that in their opinion it is only the fangs of dogs that should be white!

Both Christian and Mohammedan Albanians, dissatisfied with the poverty of their country and their incapability of developing its natural resources or profiting by them, often leave it and migrate to other parts of Turkey in search of employment. Large numbers seek military service in Turkey, Egypt, and other countries, or situations as guards, herdsmen, etc. Some of the Christians study and become doctors, lawyers, or schoolmasters. The lower classes are masons, carters, porters, servants, dairymen, butchers, etc.; their wives and children seldom accompany them, but remain at home to look after their belongings, and content themselves with an occasional visit from the assiduous bread-winner.

All Albanians call themselves Arkardasli (brothers), and when away from their homes will assist and maintain the Kapoussis or new-comers, until they obtain employment through the instrumentality of their compatriots already established in the town. Thus assistance is given in small towns to the Kapoussis to defray the expenses of his maintenance and lodging in the Khan. When he obtains a place, he repays the money in small instalments until the debt is acquitted.

The Albanian, generally a gay, reckless fellow, is always short of money: many among the better conditioned carry their fortune on their person in the shape of rich embroideries on their handsome costumes and valuable arms. In their belt is contained all the money they possess. When the fortune-seeker has to wait a long time for the fickle goddess to smile upon him, and the forbearance or generosity of his friends is exhausted, and the kemer becomes empty, he sells his fine arms and the splendid suit of clothes follows to the same fate. But the Albanian, though externally transformed, will be by no means crushed in spirit or at all less conceited in manner, even when a tattered rag has replaced the gaudy fez, and a coarse aba his fustanella and embroidered jacket. With shoes trodden down at heel he patiently lounges about under the name of Chiplak until the expected turn of fortune arrives. Should it be very long in coming, our Albanian turns the tables upon the goddess, shoulders his gun, and takes to the high road.

The bessa or truce is the time Albanians allow themselves at intervals to suspend their blood feuds; it is arranged by mutual consent between the contending parties, and is of fixed duration and strictly observed: the bitterest enemies meet and converse in perfect harmony and confidence.

The character of the Albanians is simply the mixed unhewn character of a barbarous people; they have the rough vices but also the unthinking virtues of semi-savage races. If they are not civilised enough not to be cruel, at least civilisation has not yet taught them its general lesson that honour and chivalry are unpractical relics of Middle-Age superstition, quite unworthy of the business-like man of to-day, whose eyes are steadily fixed on the main chance. The Albanian, too, can plunder, but he does it gun in hand and openly on the highway; not behind a desk or on ‘Change. His faults are the faults of an untrained violent nature, they are never mean; his virtues are those of forgotten days, and are not intended to pay. He is more often abused than praised, but it is mostly for want of knowledge; for his faults are on the surface, whilst his sterling good qualities are seen only by those who know him well, and know how to treat him.

The ties that bind this nation to its rulers have never been those of strict submission, or of sympathy. The Turkish government cannot easily forget the troubles and loss of life the conquest of Albania occasioned, nor can it feel satisfied with the manner in which imperial decrees are received by the more turbulent portion of the inhabitants with regard to the enrolment of troops and the payment of taxes; nor pass over the insolence and even danger to which its officials are often exposed.

The Mohammedan Albanians on their side deeply resent the loss of their liberty, and the forfeiture of their privileges, and reciprocate to the full the ill-feeling and abusive language of the Turks. The Turk calls the Albanian Haidout Arnaout! (Albanian brigand!) or Tellak! (bath-boy!).The Albanian regards the Turk as a doubtful friend, and a corrupt and impotent master; and if this antipathy exists between the Turks and the Albanian Moslem, it is scarcely necessary to say that it is felt far more strongly between the Turks and the Albanian Christians of Epirus and the Mirdites, who, feeling doubly injured by the oppressive rule to which they are forced to submit, and the loss of their freedom, ill-brook the authority of the Porte. The Mirdite turns his looks and aspirations towards the Slavs, while the Albanian hopes finally to share the liberty of the Greek.

The Porte, under these circumstances, had a difficult mission to fulfil in controlling this mixed multitude, and was not unjustified in looking upon it with distrust and suspicion. It now seems probable, however, that it may be relieved of the weight of this responsibility.

[extract from Fanny Janet Blunt: The People of Turkey, Twenty Years’ Residence among Bulgarians, Greeks, Albanians, Turks and Armenians, by a Consul’s Daughter and Wife. Edited by Stanley Lane Poole (London: John Murray, 1878), vol. 1, p. 62-87.]

TOP