| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1878

Edward Frederick Knight:

Early English Tourists Venture

into the Northern Albanian MountainsThe English barrister, journalist and travel writer, Edward Frederick Knight (1852-1925), spent his childhood in India and studied law at Caius College in Cambridge. He was called to the bar in 1879, but embarked upon a career in journalism instead. Knight was a great traveller and adventurer, and was the author of twenty books. In 1878, at the time of the League of Prizren, he set off with a group of friends on a tour of Montenegro and Albania. His goal in Albania was to travel though Kelmendi territory to visit the elusive and notoriously xenophobic town of Gucia/Gucinje, now in Montenegro. The trip proved to be more of an adventure than he had bargained for. The following is an excerpt from his book “Albania: a Narrative of Recent Travel” (London 1880).

The Cem River in the mountains of Kelmendi

(Photo: Ismail Gagica, August 2011).

It was pitch dark when we reached Scutari [Shkodra], and walked through the abominably roughly paved streets to the Hotel Toshli, where the brothers received us with open arms.

The next morning we held a council to decide whither we should wander next. We came to no immediate conclusion, as there was great diversity of opinion. As Robinson was expecting a remittance from London, we should most probably have to remain a few days at Scutari. Having nothing better to do, we persuaded our friend the gendarme to introduce us to a chief of the Albanian League, who was a friend of his.

The interview had to be arranged with caution, for, as our friend said, “They know here you have been to Montenegro, and may suspect your motives in wishing to question a member of the League.”

It was settled that we should go to the gendarme’s house in the afternoon; there the chief in question would meet us.

In the afternoon Jones and myself were shown by the gendarme’s Miridite servant into a room, where, squatting on mats, coffee-drinking, were our friend and a shrewd-looking old Albanian Mussulman, with deeply-lined face, and anxious and restless eyes. After the customary salutations I entered into conversation with him, the gendarme, as usual, acting as interpreter.

I told him the English wished to know what were the objects of the League.

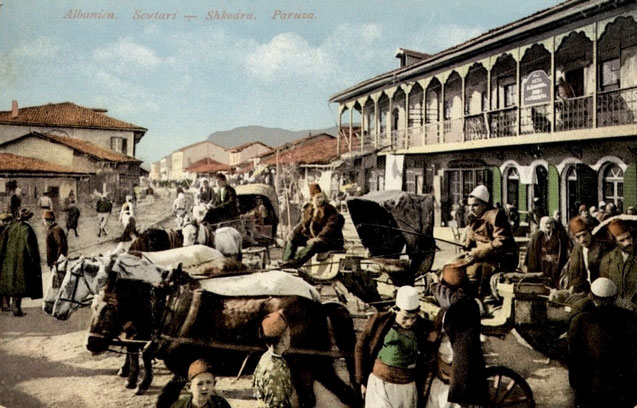

Early postcard of Shkodra.

“Our object,” he said, “is to defend our countries against the enemies that surround us. The dogs of Montenegrin, the Servian and Greek swine, all wish to steal a portion of Albania; but, praise be to Allah, we are strong. The Albanians are brave; and guns and ammunition are not wanting.”

He tried to sound me as to the views of England, for he thought this frontier dispute was absorbing all the attention of our countrymen. He said, “England is our friend. They all say here she has supplied the League with weapons and money.”

That some power—most probably Turkey has assisted the League in this way, is certain. But it is curious that all the Albanians I met were positive as to England being the friend in question.

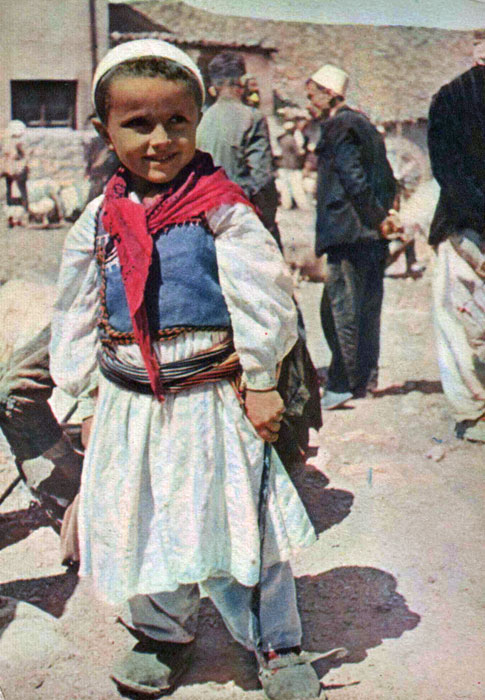

A little boy from Zadrima.

The Government of Turkey does not find favour in the eyes of the Albanians. “The Turks!” cried out the chief, angrily, “what do they do for us? Tax us, rob us—that is all. These effeminate pashas, these farmers of customs, do nothing for us in return for what they steal. Can they defend us? protect us? No! They have sold us to the cursed giaours of the Karatag [Montenegro]. I tell you we will have the Turk no more. The chiefs of the League have sworn it. Independence has been given to Montenegro—to Bulgaria. Albania shall have her independence, and the great powers shall recognize us. If not, we care not. Leave us alone; that is enough for us.”

He had now worked himself up into a furious rage, and was almost choking with it; so he stopped, drank some sherbet, then turning suddenly to me, said, “What do you English think of Midhat Pasha?”

“He is much liked by us,” I replied. “He is looked upon as one of the few honest and worthy Turkish officials.”

He seemed very pleased at hearing this, and said, “What we wish is to create an independent Albanian principality, with this Midhat Pasha as our Prince—a principality under the protectorate of England. You will see we shall have it.”

I asked him whether this League was a purely patriotic movement, or whether it was a religious one, confined to Mohammedans only.

“We are fighting for our independence,” he replied. “There are as many Christians in the League as Mussulmen. You know the Christians here are of the Latin Church, and hate the Greek Christians as much as we Mohammedans do.”

He told me that one party of the League were not averse to the occupation of Albania by some big power; not Russia, he said, nor Italy, nor Austria; but England or France. For his part he did not wish this.

With regard to the defence of Gussinje [Gucia/Gusinje], he said, “We have 35,000 men there, who will fight to the death. The Montenegrins cannot take Gussinje. Why, they never yet have fought us in the plain. The beasts can fight well enough behind their own rocks, but they are cowards to attack. When the Skipitars raise their shout, and charge with the yataghan, the Karatags tremble; they turn, they fly. Then we pursue them, seize them by their long hair, and with a sweep of our blades cut off the beasts’ heads. Ah! it is sweet to see.” And turning sharply to me, “Why do not you go to Gussinje and see the fighting? Parties leave Scodra every night for the front. I will give you a letter to Ali Bey. He will welcome you as a brother.”

The proposal was pleasing; Jones and myself at once agreed to accompany the next party to Gussinje. We knew that the expedition was rather a risky one. The garrison of Gussinje had been worked up to a high pitch of fanatical madness, and might treat us with little ceremony did they hear of our journey into the enemy’s country. Under these circumstances we thought it better that two of our party alone should go to Gussinje, while the other two could make a sporting expedition into the mountains beyond the plains of Scutari.

The next morning accordingly, Brown and Robinson, taking Marco with them, shouldered their rifles, strapped their blankets on their shoulders, and marched off towards the Miridite mountains—a lofty and wild range, inhabited by the tribe of the same name, the most savage and desperate of all the Christian highland class, a race that has waged a perpetual war with the Turk for centuries. The Miridites are exceedingly poor, in a condition of half starvation, for bodies of Turkish troops ever and anon make incursions into the debouchures of their valleys, driving off their flocks, burning their villages, and compelling them to fly for safety into the cold and utterly barren highlands.

The gendarme brought to our room at Toshli’s, the morning of our friends’ departure, another member of the League, a chief of influence. He slipped off his shoes at our door, and shuffled in, a short-legged, stout, dropsical old fellow, with not over-clean festinelle, and a four days’ beard: he had the fierce eye which is the characteristic of the Northern Albanians. The shaven head too of the Mussulman lent a peculiar ferocity to his expression. I never cast eyes upon a more bloodthirsty-looking old scoundrel. “Will your friend take some coffee or sherbet?” I asked the gendarme. “He likes raki best,” was the reply, “when no one is looking on. He is not a very strict Mohammedan in this respect.” I found few Albanians indeed had very delicate consciences when raki was in question.

This gentleman, who was introduced to us as Achmet Agha Kouchi, kept a coffee-house in the Mohammedan quarter of the town. He purposed going to Gussinje in a few days, and would be pleased if we would accompany him.

We were to visit him at his café in the afternoon, to arrange matters.

After lunch we traversed the dismal streets of the Turkish quarter till we reached the little café of our new friend. It was full of Leaguesmen, who had evidently come to inspect us. I wish I had taken a sketch of that interior. No slum of an Eastern city could show a group of more cut-throat-looking, fierce ruffians than those Scutarine conspirators.

They did not rise when we entered, but stared at us with savage, lowering looks, that betokened suspicion and hatred of the giaour.

Achmet Agha told us that a party would start the night after next for Gussinje; and that tonight there would be a meeting of the Scutarine Leaguesmen, in the mosque near the river, to decide whether we should be permitted to visit the besieged town.

In the morning he would let us know what had been decided.

In Toshli’s this evening, I read an account in a Trieste paper of a battle which had been fought near Gussinje, in which the Albanians had been victorious. Rumours of all kinds had for days been flying about the bazaar; but though Gussinje is but a three days’ march from here, nothing certain was known. Indeed the Scutarines were entirely without information on the progress of matters.

Some excitement was caused by the departure of Mr. Green to-day for Cettinje. He had of course gone thither to take a part in the negotiations now pending, the Turks having sent a representative to the Montenegrin capital, to try his utmost to arrive at an amicable solution of the difficulty. The Scutarines, however, were quite certain that Signor Green had gone off to threaten Prince Nikita with an immediate declaration of war on the part of England, did he not without delay withdraw his troops from the frontier.

The League met as usual at midnight, in the mosque, and till daybreak discussed Jones and myself. The meeting was described to us. Said some: “Let them not go; who knows that some of the men of Gussinje will not murder them as giaours? Then what difficulty we shall be in. We will have to avenge them, for they are our guests; there will be strife between the defenders of our country, and the dogs of Karatag will rejoice. Again, their blood will be upon our heads. Zutni Green will be wrath. The English will be our friends no longer.”However, the dissentients were in the minority. The League of Scutari gave its permission to our departure.

We were advised to wear the fez instead of our English hats, as this would reduce the risk of our irritating the intensely excited inhabitants of Gussinje: accordingly we purchased two of the orthodox head-coverings.

Achmet Agha again called on us; he seemed rather uncomfortable. We could see he had heard something about us, and did not like to carry out his promise. Said he: “Who are you? Why do you wish to go to Gussinje?” We replied: “In England we will write a book. The English wish to know what the Albanian League means, whether it is good. It is for that we wish to go to Gussinje, that we may see, and be able to tell our countrymen the truth. “Ah,” he said, “so your 'krail,' your chiefs, have sent you for this. Mir, mir—it is good.”

Then he paused, and said abruptly, “We shall not go to-morrow.”

“Why not?”

“Because we know not how the other Leaguesmen will receive you. We must first send to inquire of our general, Ali Bey, if he will have you.”

This did not sound very pleasant to us. Ultimately he agreed to take us on the morrow to a hut two hours distant from Gussinje; there he would leave us while he rode into the town, to acquaint the chieftains with our wishes, and obtain permission for us to visit Ali Bey.

The next morning we rose at daybreak, and found a strong “bora” was blowing, and the snow lay thick on the distant mountains.

We prepared for the start.

Luggage we took none, except one blanket; but as it promised to be exceedingly cold in the mountains, we each put on two flannel shirts and two pairs of socks.

View of Hoti and Lake Shkodra

from Brigjja e Hotit

(Photo: Robert Elsie, May 2013).

Achmet Agha called two hours after his time; he seemed confused and troubled. Our host, Toshli, came forward as interpreter, for I managed to make out a good deal he said. With him I conversed in a strange mixture of Italian and Greek, one of the six compound tongues I had to invent in Albania in order to get on with the different people I met.

Said Achmet Agha, “I cannot go with you. I have been told by the authorities that if anything happens to you I shall be held responsible; my house and property will all be confiscated. Besides, I have to tell you that you are forbidden on any account to go to Gussinje; the pasha will not have it.” This all seemed very strange. That the Turkish pasha and police authorities should have acted thus seemed improbable. We afterwards found they did not even know anything about our intended journey.

We did, however, hear something later on, which led us to very strongly suspect that the attempt to stop us originated in a certain foreign consulate at Scutari.

Naturally suspicious and jealous of English influence in Turkey, the representatives of this power concluded that our government had sent us here on some secret errand; and so, not being able to discover the object of our mission, attempted to frustrate it altogether in an underhand manner.

Jones and myself had now thoroughly made up our minds that we would go to Gussinje, in spite of an over-officious consul, so we proceeded to hunt about Scutari for a guide and dragoman.

No one could we find. Those we spoke to smiled grimly drew their hands significantly across their throats, and emphatically objected to go anywhere near the hot little town.

The mountains of Kelmendi

(Photo: Ismail Gagica, August 2011).

One person, however, did volunteer to accompany us. This was the English Consul’s cook. He was a plucky little Albanian, very vivacious and clever. He spoke two words of nearly every language in Europe, and in default of better, would make a very fair dragoman for us. He had adopted European costume, and wore jauntily on his head an English army forage cap, the gift of the British sergeant who accompanied the frontier commissioners last May. This cook was a man of some rank. In Albania, a calling such as was his is not derogatory to a gentleman. We had made his acquaintance at Toshli’s, where he was famed for his skill as a billiard-player. He went to Mrs. Green, told her of our intended journey, and implored her to give him leave of absence, in order that he might guide and protect the Inglezi travellers. Alas! It could not be; his presence was indispensable in the consulate kitchen. Cooks are not to be picked up every day in Scutari, at any rate such cooks as this, for we had several opportunities of perceiving how skilled he was in his profession, under Mr. Green’s hospitable roof.

No one to be found to come with us! This looked bad; we almost despaired of effecting our purpose, for to find our way alone across the roadless mountains would have been impossible. To have travelled among the savage Arnauts, without knowing ten words of their language—madness.

Ali Pasha of Gucia (1821-1885).

As we discontentedly discussed the question in our bedroom, the head cavasse of the English consulate was announced. He brought with him a handsome, and very pleasant-looking Albanian Mussulman, evidently a man of high rank, superbly dressed and armed. “This,” said the cavasse, “is the Boulim-Bashi of KIementi. He will accompany you to Klementi, which is a day’s march from Gussinje. There he will hand you over to the chieftain of the Klementi, Nik Leka, who is a friend of Signor Green. He will say to Nik Leka, these are friends of Signor Green; treat them as his brothers, and if the danger be not too great take them to Ali Bey.

My readers can imagine our delight. We could not travel under better auspices. The condition of a boulim-bashi is curious. The Turks, as I have before said, have never really conquered or assimilated Albania; the Christian highlanders are allowed considerable independence. Now, each Arnaut tribe is obliged to elect from the Mussulmen of Scutari a representative, a sort of consul, who mediates between it and the Turkish Government, who acts as their advocate in case of any dispute. As he is chosen by the tribe from among the townsmen of rank, and as he can be dismissed any day if the highlanders in any way object to him, the boulim-bashi is always a popular man, liked by the tribe he represents, and a very safe person in whose company to travel among the highlands, for he is sure to be known to, and treated as a friend, by every man met on the way. It was a great honour to be thus escorted, and we afterwards discovered the cause that led to the kind proposal. The men of Klementi are deeply indebted to our consul, who took their part in a certain quarrel between them and the Turkish Government, in which justice was entirely on their side. Grateful for this, the Klementis are ever glad to do any service for Zutni Green. Thus it was that we as friends of the consul received this invitation. The Klementi is the most powerful tribe of this district. There are 6000 fighting men, all armed with Martini-Henry rifles, stolen from the Turks. Their chieftain, Nik Leka, to whom the boulim-bashi was to escort us, is the hero of the Scutarine Christians. The timid townspeople of the Latin faith, unarmed as they are by law, live in fear of the Mohammedan population, who have more than once fallen on and massacred them. It is to the armed Arnauts of the hills, their fellow-Christians, that they look for protection, for these are better warriors than the Mussulmen themselves, never have been a subject rate, but stalk, bristling with arms, through the bazaars of the cities on market days, as erect and haughty as the most blue-blooded young Mohammedan emir of them all.

This Nik Leka had a little adventure recently in the bazaar of Scutari. He was discussing some matter with a young Mussulman of rank, who had three retainers with him. A quarrel ensued. The other called the Arnaut chief a dog of a Christian. Nik Leka is a man of few words. He whipped out his yataghan with his right hand, seized his enemy by the little tail of hair which the faithful leave on their closely-shaven heads to give Mahomet something to lay hold on when he pulls them into Paradise, and the next moment there was a flash of bright steel, and the Arnaut held up a bleeding head, while the body fell into the foul gutter below. The man’s retainers fell upon Nik Leka, but the wiry highlander was too much for the effeminate townsmen. He slew two of them, the third escaped; then he picked up the three heads with a grim smile, tucked them under his arms, and marched off to his mountains, where he exhibited the ghastly trophies to the tribesmen.

It was settled that we should start early on the following morning. Then the boulim-bashi bowed low, shook hands, and left us. We had learnt something of the nature of the place we were about to visit from Mr. Green and others. About three days’ march from Scutari, across the great Klementi mountains, there is a long and beautiful valley, which penetrates deeply into the central range of the Mount Scardus. Down this valley flows the White Drin, a stream of considerable importance, that flows into the Adriatic, near Alessio [Lezha]. In this valley are Ipek [Peja], Jakova [Gjakova], and Priserin [Prizren], three of the most interesting cities of Albania, inhabited by a population very skilled in the working of metals. The most beautiful saddlery, filigree work, gold-hilted and jewelled yataghans and pistols, are here worked by an industrious people.

The Hoti switchback trail (Leqet e Hotit)

down to Kelmendi"

(Photo: Ismail Gagica, August 2011).

But the population of these towns is ferociously fanatical. Surrounded as they are by Christians, knowing that the day is not far off when the rising ambitions and energies of the oppressed race will drive them from their homes eastwards and southwards, the Mohammedans here hate the Christians with a hatred more intense than even the followers of this fanatical creed entertain in other parts. At the very head of this valley of the Drin, where the river springs out from the grey rock, is a ridge of forest-clad mountain, the ancient Pindus, which forms the watershed of the tributaries of the westward-flowing Drin, and Bojana, and the Lim, a river that flows northwards, joining the Drina and the Save, across Bosnia and Servia, till it ultimately pours its waters into the mighty Danube at Belgrade. At the head of the valley of the Lim, situated in the centre of a green and fertile cirque, surrounded by stupendous mountains, is the little town or village of Gussinje, a congregation of sordid wooden huts. It is a place of great strategic importance, for just behind it, on the ridge of the forest-clad mountains, Montenegro, Bosnia, and Albania join.

By the provisions of the treaty of Berlin, Gussinje and its neighbourhood was handed over to the Black Mountaineers—wherefore it is difficult to see.

As conquerors in the war, it seems just enough that the Montenegrins should have acquired Antivari by that treaty, a place of no strategic importance, yet which gave them what they so long and eagerly thirsted for, a seaport. But it was decidedly a mistake to extend Prince Nikita’s territory beyond the mountain ridge, a natural frontier, down into the valley of the Lim, giving a command of it—a standing menace to Turkey and Bosnia, a bone of many future contentions. It must be remembered, too, that the inhabitants of the district to be given up are not Sclav in race or language—not of the Greek church—but Mussulmen or Roman Catholics. The Montenegrins have been made too much of lately. They now imagine that they are a great people, and have a holy mission of aggrandisement at the expense of Turkey.

The gorge of Kelmendi

(Photo: Ismail Gagica, August 2011).

Gussinje is a curious sort of a place, and has never enjoyed a very sweet reputation. As in all parts of Northern Albania, the people do pretty much what they like, and do not feel the Turkish yoke very heavily. Situated as it is on the frontier, it has become a city of refuge. Montenegrin renegades whose country has become too hot for them, Bosnian Mohammedan refugees, and vagabonds of all sorts, have flocked hither. It is in this town of Gussinje that the chiefs of the Albanian League have concentrated their forces, determined to fight to the bitter end, in spite of the Austrian troops in Bosnia to the north of them, Turkish troops in their rear, Montenegrins before their walls, and the doubtful neutrality of the Christian Arnauts, who are all round them in the mountains, lying in wait to murder and strip small parties of either side—for this is the idea of neutrality among these people, an armed neutrality with a vengeance. Thirty-five thousand Albanians, we were told, occupy Gussinje, at the head of whom is Ali Bey.

Ali Pasha, as he has styled himself, is a Gussinian of rank, owner of lands and houses in the town and neighbourhood, a man of great intelligence, and a devout Mussulman.

He was one of the principal people implicated in the assassination of Mehemet Ali at Jakova.

This general, as my readers will remember, was sent by the Porte on the dangerous mission of negotiating the transfer of Turkish territory to her enemies. He was strongly advised not to venture into that hotbed of fanaticism and fierce patriotism, Jakova. The League held possession of the town; the population was worked up to the highest pitch of excitement; every one knew the history of the envoy. As a foreigner, a Pasha’s favourite boy, a renegade, he was certain to be disliked and suspected by rigid Mussulmen, and was the very last man that should have been sent on so delicate an errand. It is rumoured that the jealousy of his enemies at Constantinople sent him on this surely fatal journey.

His death was decided on by the League. The projected murder was talked about freely in the bazaars of Albania fully two weeks before it was perpetrated. Contrary to advice, he entered Jakova. He had not long been there before the house in which he and his companions were shut up, was besieged by a furious mob. One man, a Franciscan father, whom I met at Scutari, was with him, and managed to escape, disguised as an Arnaut.

Mehemet, seeing that resistance was hopeless, died like a brave man. He opened a door, rushed out, unarmed, with hands stretched out, into the thick of his enemies, crying, “Kill me, but spare the others.” He was beheaded, and his head was stuck on a pole, and held up to the jeerings and desecrations of the populace.

We were up at daybreak the next day. It was a sunny, exhilarating morning that seemed to send fresh blood coursing through our veins as we mounted Rosso and Effendi, and rode through the Mohammedan quarter to the house of the boulim-bashi. Our luggage was simple enough. I had one blanket and my waterproof, strapped behind me on Effendi’s saddle; while Jones carried, in the same way, a saddle-bag of provisions and his waterproof. The house of the boulim-bashi was enclosed within lofty walls, as are all the residences of the Mussulmen. We were ushered into a large room, where the brother of the boulim-bashi received us smiling, and motioned to us to be seated on the luxurious cushions which were strewed on the thickly-carpeted floor. He was a tall and very handsome man, like most of his countrymen, possessing small, delicately cut features, and tiny hands and feet. He looked like an aristocrat, and his costume was exceedingly rich.

The boulim-bashi came in with coffee and sherbets. He had thrown off the dress of the town, with its ample festinelle and rich linen, and had donned the simpler dress of the Arnaut chieftain, which showed off his fine person to great advantage. His cartridge-boxes betokened the man of rank, being of gold, beautifully worked, as were the handles of the pistols in his variegated silken sash. The coffee was prepared over a silver brazier on the floor, and the cups were handed to us on trays, covered with napkins cleverly embroidered in coloured silk and golden thread.

We found that we were expected to take these napkins away with us. We did not know the custom, but our host soon set us right.

There is something particularly pleasing and refined in the manners of the high-caste Albanians. Their politeness is charming; they anticipate your every want; and their movements have a catlike softness, noiselessness, and suppleness about them, which is very striking.The boulim-bashi seized his Martini-Henry, leapt on his horse, an active-looking little grey, with undocked mane and tail.

We were soon out of the town, and then broke into a canter, which we kept up across the plain of Scutari till we reached our old friend the khan, at Koplik.

We felt very jolly this morning. We had made a start. There was a spice of adventure and risk in this expedition, that lent it zest, and excited us. How we were to get on at Gussinje we did not know: our guide spoke no language but his own. It was improbable that we should find any one in the mountains who could understand us. And again, how would Ali Bey and his men treat us. We had no valid excuse for visiting him. Would they know that we had interviewed the prince and war minister of Montenegro? If so, our reception might prove almost too warm. We trusted to luck, and determined to see all we could.

The gorge of Kelmendi

(Photo: Ismail Gagica, August 2011).

At Koplik we left the track by the lake, and turned to the right, towards the desolate and lofty mountain range.

These were the very mountains that the Turks at Helm seemed so afraid of, as being inhabited by the fiercest and bravest of the Arnaut tribes, addicted to plundering Turk and Montenegrin indiscriminately. With our friend, the representative of the tribe, we were, however, quite safe, certain of being received with every hospitality; and as friends of Zutni Green, every man of the tribe would be friendly to us. For the Arnaut is very grateful, is never treacherous—and once a friend is always a friend, and an excellent friend too.

We gradually reached the foot of the mountains, and then our route lay through the heart of them, for to reach Klementi we had to cross this stupendous chain. For seven hours we were nearly constantly ascending. There was no pretence at a road. We had often to dismount to haul our horses up a higher block of rock than usual, and had to use the greatest care, as we rode along some track not two feet wide with a wall of rock on one side and a precipice a thousand feet in depth on the other.

The shades of night were falling—it would be impossible to travel after dark on such a route. But the boulim-bashi had timed himself well. It was just dusk when we heard that welcome sound to the traveller—the baying of dogs. Our guide signed to us to dismount. We led our horses down an incline, when suddenly a door opened, and a blaze of light fell on us and dazzled our eyes. A gigantic Arnaut, gun in hand, came out suspiciously. He at once recognized our companion, and kissed him affectionately.

On hearing that we were English, friends of Zutni Green, he shook us kindly by the hand, and bid us enter.

“Bramiamir. Mir s’erd” (A good night to you. Be welcome) were the salutations we exchanged on entering the house. Then, according to Albanian custom, we unstrapped our arms, and handed them to our post (a sign of confidence in a friend), who proceeded to suspend them with his own on the wall.

A village in upper Kelmendi

(Photo: Ismail Gagica, August 2011).

We were seated on mats by the blazing fire, and the women pulled off our boots. It was a curious scene, highly interesting, and taking one very far indeed from Europe and civilization. A large room, the walls of rough stone, admitting the wind freely; the roof of huge, rough-hewn rafters of larch—wall and roof blackened with smoke; the floor of clay; in the centre a fire of great logs, the smoke allowed to find an exit as it could, the result being very unpleasant to unaccustomed eyes; no lamps or rushlights, but a pale and flickering light given out from a sort of iron cup, supported on a rod, into which little chips of resinous wood are occasionally thrown; the walls decorated with arms, the only ornaments in the place. A few cups, a bowl, an iron pan, and one or two other utensils, complete the ménage. This is the house of a great man, a chieftain; and we were told the name of the place is Castrati. A large family occupied the hut, for it was no more. There were several women and young men.

By the fireside there sat a very old crone, who paid no attention to what was going on, but rocked her palsied body too and fro, and mumbled constantly to herself. A little child — maybe a great-great-grandchild — whose sturdy limbs were a strong contrast to the withered legs and arms of the old woman, sat by her side. The grandame attempted now and then to stroke the little thing’s head, the only sign she showed of being conscious of the world around her. All the occupants of the hut were remarkably handsome. Leslie, who so well delineates pretty childhood, should visit Albania. I verily believe no children in the world are so beautiful as there little Arnauts. Their costume is not graceful. A woollen sack is thrown over them, and their arms and legs are thickly swathed with the same material.

Old shingled house in upper Kelmendi

(Photo: Ismail Gagica, August 2011).

They are quaint little things, and the smallest has the proud, fearless, free carriage of his fine race. There was one little fellow who stood in front of us here, erect, with head well up, and hands behind his back. He stared at us for a long time with big, wondering eyes, and a wonderful smile at the corners of the mouth, and then came boldly up to investigate the material of our clothing, which was evidently new to the little mountaineer.

Dinner was soon prepared. The boulim-bashi had brought some sweet cakes with him, and some mutton, which he cut into small lumps, and stuck on a skewer. They looked for all the world like catsmeat; but, when peppered, salted, and grilled in the glowing fire, they turned out those sweet and succulent morsels so appreciated by every old campaigner, known under the name of “kybobs.” According to Eastern custom the wife of the master of the house poured water over our hands from an iron jar, and then we commenced to devour our dinner with our fingers, washing it down with excellent raki.

This lady of the house, by-the-bye, created a great impression on both our hearts. She was indeed exceedingly comely. Her figure had not been spoiled by labour, as are those of most of the countrywomen, nor by the want of exercise and cramped sitting position in which the legs soon lose their shape, as is the case with most of the townswomen. Her legs were bare, not swathed in the ugly manner in usage when out of doors, and very shapely legs and ankles she possessed. Her face was oval, of a rich carnation in tint. Her mouth small, and very beautiful; but her eyes were her chief feature—long, almond-shaped, and with a voluptuous dreaminess in them. Their length owed nothing to the artificial blackening of their corners with henna. She saw we admired her, and was evidently pleased. She laughed, and made eyes at us throughout the evening; and at night, when all the inmates of the room rolled themselves up in their blankets, and stretched themselves round the fire in a circle, feet to the blaze, she brought us some mats for pillows, and tucked us in very nicely with her delicate fingers.

“Bothmir, mik” (Good health, friends), was the frequent challenge of our jovial host. He insisted on our drinking a fair amount of raki. He was not backward himself; I am sorry to say even an Arnaut will get drunk upon occasion. After dinner a happy thought struck me. I rose, and plunging my hand into our saddle-bag, produced a bottle of brandy we had brought with us from Scutari. This was a great and unaccustomed luxury to the Arnauts. I do not think they had ever tasted it before. They smacked their lips over it, and repeatedly said, “Raki Inglesi mir, mir” (The English raki is good).

At last to bed. Comfortably rolled up in blankets, in spite of insects—we did not mind anything in that line now—we slept till daybreak.

The boulim-bashi then awoke us. The fire was raked up, coffee was made, our horses were saddled, the stirrup-cup was drunk over our good-byes to our friends, and we were off.

The Arnauts are very proud. It would be a grievous insult to offer a man money in return for his hospitality. The proper thing to do is to distribute what you intend to give among the children. When you are gone, the mother goes round and collects it from her offspring; it is then put away, to be expended in sugar, salt, and other necessaries, on the next market-day at Scutari.

At this great elevation the morning was bitterly cold. The aspect was very desolate—a wilderness of rock and stone, with scanty vegetation. Far away, thousands of feet beneath us, stretched the White sheet of the Lake of Scutari, looking cold in the early morning, with the bleak grey Montenegrin mountains in the background.

From sunrise to sunset we rode over the trackless and almost inaccessible mountains. We met several men during the day, fine and fierce-looking members of the Klementi tribe. Every one had a Martini-Henry rifle and a belt of cartridges. The stories we had heard of these people from the Turks at Helm were evidently true; these weapons had never been bought. Indeed their owners had little idea of their value. One mountaineer we met pointed to his rifle, and said, “Inghilterra, sa paré?” signifying that he wished to know what was its value in England. On hearing the amount he seemed much astonished, smiled grimly, stroked the weapon, and said, “Ah! the Skipitar get them for less than that.”

Such an abundance of cartridges have these highlanders managed to steal that it is a common sight to see a shepherd firing his rifle in the air, at frequent intervals, to drive his sheep. The people we passed all stopped, and questioned the boulim-bashi as to who we were, and whither we were bound. On hearing that Gussinje was our destination they looked surprised, and made that clicking noise with the tongue and teeth which with us signifies pity or annoyance—in Albania, mere wonder or admiration. The sign language of this people is so utterly different from ours that it is impossible to get on with them at first. For instance, they do not shake the head when they wish to refuse anything, but bow and wave the hand, in a manner which would lead any one to imagine they meant to accept.

It was evident they all looked on us as doomed if we entered Gussinje. So far I could not make out whether they sympathized with the rebels or not.

Towards midday we reached the summit of the range, and on turning a bluff of rock there lay beneath us one of the most magnificent gorges I had ever seen, even in the Alps. The great mountain was rent into a profound ravine, whose sides were nearly perpendicular. There were places where the precipice ran down sheer, for 4000 feet at least. Where there was any footing, grand larches and beeches, tinted with the golden shades of autumn, covered the slopes. Far below one heard the roar of the great torrent, but a purple haze lay at the bottom of the gorge, and concealed the foaming waters. This ravine forms the frontier of Montenegro and Albania. As Jones suggested a very scientific-looking frontier too.

The gorge of Kelmendi

(Photo: Ismail Gagica, August 2011).

Our destination, the village of Klementi, was situated on the edge of the torrent, some miles higher up the valley. We now had to descend from the mountain to the bottom of the ravine. A perilous descent it was. The path, a mere goat-track, zigzagged down the precipice. It was necessary to dismount, and watch the horses carefully. They stumbled every moment, and slid rather than walked. In places the path would give a sharp turn, and here the boulimbashi would hold on to each animal’s tail as he passed the awkward corner, to prevent him going right over the edge. There were some very nasty bits, and even these mountain horses trembled with nervousness at times.

We passed a house on the bank of the torrent in the afternoon. The whole family came out to see the travellers. These people were friends of our companion. The men came out, shook hands with us, and then entered into an animated conversation with the boulim-bashi on the subject of the war. While we sat on our saddles outside the house the women brought to us refreshments, apples, cakes, and raki, first taking our hands and kissing them respectfully.

A Catholic church in Kelmendi

(Photo: Ismail Gagica, August 2011).

This was a very long day’s journey. Now riding, and now walking, we ascended the ravine, fording the torrent several times, whenever one or the other side of it afforded the better path.

The scenery was grand, but desolate; in the higher portion of the valley the forests that clothed the lower end were wanting. Great walls of rock fell sheer into the turbulent stream; and in places great fan-shaped slopes of debris—masses of mountain broken up by hurricanes—jutted out across the gorge, damming up the waters into profound pools. These gigantic wastes of black stone, streaked as they were by patches of snow in strong contrast with their whiteness, gave an impressive weirdness and desolation to the scenery.

About an hour after dark we halted before a large two-storied hut. “Scpiia Nik Leka,” said the boulim-bashi—the house of Nik Leka. Here, then, we were at last in the stronghold of the notorious Arnaut chieftain. We entered the large lower room, which in every respect was similar to that in which we passed the previous night at Castrati. There were at least fifteen people squatting round the fire—men, women, and children. A tall, splendidly-built, and very handsome man came up and greeted us. He was about fifty years of age, very dark, with a much-lined, sad-looking face. He had fine black eyes, deeply sunk, and surmounted by bushy black eyebrows. There was something exceedingly frank and noble in his look—a man one could trust.

This turned out to be the brother of Nik Leka, and, as we afterwards found, much resembled that chieftain. We sat down by the fire, and all were busy in attending to our comforts, when a door opened, and, to our astonishment, there bustled in a jolly-looking little fat Franciscan monk, a very Friar Tuck. He wore the brown frock and girdle of his order; but, like all the Franciscan missionaries in Turkey, his head was covered with a fez. He was followed by a quaint, lean, smiling old Arnaut with a lamp, a simple, good-natured-looking being—the faithful old servant of the mission; he had been for forty years in the service of the Franciscans.

The friar came up to us and shook us by the hands in a most cordial manner. “Come up the mission,” he said; “come up to the mission, and stay with us. Ah! what joy to see Europeans up in our wilderness! Come along!” and he fairly dragged us off.

Not thirty yards distant was the mission-house, a very comfortable establishment for this country—a low building, with a small church adjoining it. At the door we were met by the three other brothers, as cordial and jolly as the first.

Never did traveller fall into better hands. They all bustled about, jabbering and laughing incessantly, doing all they could for our comfort. Maccaroni and mutton kybobs were soon prepared; and they stood round, pressing us to eat, and helping us to abundant portions as we sat at the table.

I have seldom heard men laugh so heartily and boisterously as did our jolly hosts. The feeblest joke set them off in a roar. “This,” said the fat little Father Luigi, pointing to the smiling servant,” this is our Lord Mayor; he looks after our corporation—ha! ha! ha!”

The dinner over, we sat down over pipes and coffee, and talked for half the night. They were really glad to see us; never were strangers so quickly made at home as we were. Of course the conversation soon turned on the object of our journey.“Go to Gussinje!” said Father John; “impossible! You cannot go. Why they will at once cut your throat. These Turchi at Gussinje are animals—beasts—swine. O, my dear brother Edouardo, you must not go. Why, even we dare not go there; the Arnauts dare not go. Nik Leka went there three days ago, to see Ali Bey; for that beast desires an alliance with the Klementi. Nik Leka has not returned; we fear they have killed him. If so, God help this country; for the Klementis will take their guns and yataghans, and march on Gussinje to avenge their chief.”

This did not sound very encouraging to us; but we had come so far that we did not relish the idea of abandoning our project now. We knew the timid monks would most probably, with very good intentions, exaggerate the dangers. As they were the only people we could converse with, we saw it would be necessary to impress them with the absolute necessity of our progressing, else they would lend us no assistance in what they considered to be a fatal journey.

Our four hosts were Italians; Luigi came from Turin, John from Naples, and the two others from Modena. I am not a proficient at Italian, so we conversed in dog Latin, putting in an Italian word now and then, when we could not call up the Latin equivalent. It was a curious mixture, but we got on fairly well with it. I had a little conversation with Jones; he was as determined as myself to visit Gussinje if at all feasible; so we decided to dissimulate a little, in order to obtain the very necessary assistance of our friends.

I said, “I know to go to Gussinje is dangerous—very dangerous possibly; but we have been sent to see Ali Bey at all hazards, and must not go back without doing so. We have friends at Gussinje, and I do not think we run so much risk as you imagine.”

The worthy monks now, of course, concluded that we were political envoys; that our mission was secret, and not to be divulged to them; but that its object was to settle the Gussinje difficulty and hinder bloodshed.

They then saw that we were right in insisting in running the risk, for it was our duty to do so. They would do likewise in our place. They looked very sad, shook their heads, and said, “Ah, my brothers, but you go to a certain death. However, as you must go, we will help you; we will write a letter in Arnaut to Ali Bey, asking whether he will see you, and send men to escort you to the town. The brother of Nik Leka will take the letter. To-morrow you can ride to the hut of Gropa, in the mountain; it is but two hours from Gussinje. There you can await the reply.”

The letter was written. I did not quite like the idea of playing the amateur diplomatist in this way; but we had gone too far to go back now, and without doing this there was no chance of our seeing Gussinje.

The missionaries evidently looked upon and admired us as noble martyrs, sacrificing our lives to duty. They insisted on our drinking an abundance of wine. I suppose they thought this was our last chance of so doing. We found from them (and what they said was confirmed by others) that we had been greatly misinformed by the leaguesmen of Scutari as to the strength and nature of the organization. There were not 35,000 men at Gussinje, but between 6000 and 7000. These were all Mussulmen—Albanians and Bosnian refugees, and deserters from the Turkish army—a frightful rabble, the scum of this part of Europe. Artillery they had none.

They told us that an army of 10,000 Montenegrins, with some field artillery, was encamped in a strong position, not two hours’ march from Gussinje.The general of the Black Mountaineers was Marco Milano, a man who has already made himself a name in former wars. Of him, most probably, the world will hear more some day. From all accounts he is a man of uncommon ability, one of those strong characters that inspire confidence in all whom they come across. He is an Albanian by birth, from the neighbourhood of Gussinje. Irritated by some injustice he had received at the hands of the Turks, he fled from his native land, and took refuge in the Black Mountain, where his talents soon brought him to the front. As a renegade always is, he is the bitterest foe to his race, and his voice is ever for a policy of war and aggression. This, at any rate, is his reputation in Albania.

As for the Catholic Arnauts, who the Scutarines told us were fighting for the league, not one of these people sympathized with the insurgents in the slightest degree. They knew too well that if these Mussulmen succeeded in their projects it would go hard with the Christians. At this time the mollahs in Gussinje had taken up arms, and were exciting the population to religious frenzy, preaching the death of all infidels. Ali Bey, a wise man, was indeed working hard to gain as allies the powerful Arnaut tribes. He had invited Nik Leka, the most influential chieftain of the north, to Gussinje for this object. “Nik Leka,” said Padre Luigi, “will talk to him—talk as much as Ali likes—he is a regular diplomat; but fight for the beasts of Turchi—not he. He may promise to allow bands of men to go unmolested through these mountains on their way to Gussinje, but he will want an equivalent for that. The Arnauts hate the Montenegrins and Turchi alike; most probably they will shoot and plunder detached parties of both sides.”

The missionaries spoke very highly of the Christian highlanders.

“Ah! they have many virtues,” they said. “Good friends, good fathers, good husbands; kind to each other, truthful, hospitable, never treacherous; they are a noble people. But,” continued Luigi with a sigh, “they are such savages, so utterly indifferent to human life. They have but one absorbing vice, and that is their love of murder.”

This cruel vendetta of theirs, which decimates the population, is horrible. There are no really old men. Every man is murdered sooner or later. It is thus they wish to die. To die in bed is a disgrace. In battle they behead their own wounded friends; this is looked on as a favour; for to survive, maimed and unfit for war, would bring lasting reproach on a warrior and his family.

Nik Leka’s brother walked off with the letter for Ali Bey at midnight. He carefully loaded his pistols and rifle before starting.

The next morning we were up early. The good priests would not hear of our leaving them till after the midday meal. “Gropa is but three hours or so from here,” they said; “you have lots of time to stay and look over our church.”

The little mission-house of Selz [Selca], as this the chief hamlet of the Klementi is called, is built on a terrace in the hill side, which commands a grand view of the ravine; gigantic bare cliffs of dark stone shut it in on every side. A small graveyard, where are buried all the monks that have died since the institution of the mission, lies to the front of the residence.

We went inside the little chapel. Very primitive and rough paintings of Biblical incidents ornamented the walls, the productions of the monks. Most of these were some 200 years old at least. The Franciscans have undoubtedly done much good in Albania. They have been here from a very remote time. They have suffered persecutions, have died the death of martyrs, but have succeeded in completely winning the affections of the wild Arnauts. As Luigi said to me, “Why, should one of us be ill-used by the Turks, the whole of the mountains would rise in our defence. We need fear nothing here now.” The headquarters of the order in Albania is at Scutari, where there is a large convent. I was much struck by the evidently sincere respect and love all the mountaineers entertained for their spiritual fathers. One could see that these men must be doing good here.

Before we started for Gropa, the snow began to fall heavily. We bid adieu to our good hosts. They kissed us and wept over us, for they feared we should never return, and insisted on filling our saddle-bag with wine, maize, bread, and mutton. Gropa, which signifies in the Albanian tongue the hollow, is not a village, but a miserable one-roomed hut, situated at the extreme end of the ravine, by the source of the torrent.

The path was coated with ice, and very perilous for the horses. Our guide, a savage-looking Klementi, walked bare-footed over the sharp stones and frozen snow with utter indifference.

The hut was nearly snowed up when we reached it. It was a desolate spot. A black pine-wood rose behind it on the hill-side. An hour’s walk through this would have brought us to the summit of the ridge which overlooks Gussinje. The hut was inhabited by a man, his wife, and one child. A blazing fire was made up; then converting our mutton into kybobs, we made a capital dinner. They gave us coffee, but sugar they had none. Our guide, who had lately walked bare-footed over the ice quite at his ease all the time, now placed his feet in the ashes of the fire with a like indifference. Extremities of heat and cold affected the hardy highlander very little.

Our host was a musician in his way. He took down his mandolin, and with it accompanied one of the monotonous songs of his country. The Albanian mandolin is like a small banjo with three strings, and is played not with the fingers, but a chip of hard wood or bone.

These Albanian songs are not unpleasing, barbarous as is their music. The first line of each verse is the same as the last line of the preceding verse. There is a peculiar sadness and subdued fierceness in the way they sing which is really very affecting. The song is always of war, of victories over the Karatag, feuds with the Turk, or the doings of the heroic Scanderbeg. The mandolin is peculiar to Albania. The guzla of Montenegro has but one string, and is played with a bow like a violin.

At midnight we were awakened by the entry of two men. One was the brother of Nik Leka; the other a Bosnian Mussulman, by his dress. The Arnaut clapped me on the back. “Mir, Mir,” he said, “Gussinje.” Then he pointed to a letter. I understood what he meant. Ali Bey had given his permission, had written a letter to the fathers to that effect, and had sent this Bosnian soldier with it to Seltz. The soldier returned to Gussinje at once, while Nik Leka’s brother also left us, to carry the epistle to the Franciscan mission. All seemed now to be going well, and very delighted we were. We should see Gussinje after all.

It was early the next morning, when Father John suddenly made his appearance at the hut. He looked alarmed and anxious, and talked rapidly to our host. Something unpleasant had evidently occurred. We waited patiently till he vouchsafed to explain matters.

“I have heard from Ali Bey,” he said. “Here is his letter. I will translate it to you. He writes thus:“To Father John, greeting. We have read—we have understood. The chiefs have assembled. If these people will be hostages, will guarantee that Marco Milano withdraw the Karatags within three days, let them come to Gussinje; if not, they had better not come. From Ali Pasha.”

This was hardly what could be called a hearty welcome. Said John, “You understand what that means. If you can guarantee that the Montenegrins withdraw their troops.”—

“We cannot do that.”

“Of course not. Well, if you go they will wait three days, then cut off your heads. Now Nik Leka’s brother has also brought this news from Gussinje. When they heard of your arrival, some of the men said, ‘We have heard of these people. They have been to Podgoritza; they are friends of the Montenegrin chiefs. They must be spies. One is a red-bearded Russian (this was Jones). They are accursed giaour traitors.’ Then thirty men decided to leave Gussinje last night, and surprise and murder you here in this hut. Ali Bey heard of it, and stopped them. But Nik Leka’s brother says that you had better not stay here. The Gussinians are violently excited about you; they thirst for your blood. Come back to Seltz.”

We were sitting down to breakfast when we heard all this cheering and appetizing information. My back was to the door, as was Jones’s, when heard a noise outside, and the next moment I saw the Franciscan drop the meat he was holding, turn very pale, and stare in a frightened way in that direction. I turned; the doorway was blocked up by two men, evidently two of the defenders of Gussinje—one in Bosnian dress, one in Albanian festinelle. Both were armed to the teeth. Their faces were not prepossessing. There was a fierce, stern look in their eyes, which wandered anxiously and fiercely round the hut, and a determined expression in their tightly compressed lips, which meant mischief. Whether more were behind, we could not yet see.

Jones and myself were unarmed. According to the custom of the country, we had delivered our revolvers over to our host. He too, and also the priest, were without weapons. The two parties looked at each other without speaking for a moment or two. Our host’s wife took her child by the hand, and looked steadily on with compressed lips, to see what would happen next. An Arnaut woman is familiar with bloodshed. However, bloodshed was not intended, it seemed. “We are envoys from Ali Pasta,” said the Albanian. “Come in, then,” said our host, suspiciously.

They entered, but seemed ill at ease, and suspicious of foul play. However, we made no advance towards our arms, and keeping a sharp eye on the men, continued to eat our kybobs. They sat by us.

The Albanian went on, the Franciscan translating,—”Ali Bey will see these Englishmen, but he does not wish them to enter the town; he cannot rely on his men. Ali Bey is but one man; he cannot protect them, if some wish evil to these men. Ali Bey and the chiefs will therefore meet them outside the town. Let them come with us.”

It seemed improbable that Ali should have sent these men with another message, so soon after the first. The Albanian is deliberate in counsel, and does not alter his mind in this way as a rule.

“Do not go,” whispered the Franciscan. “Do not believe them; there is some treachery.” After what we had heard, we thought our friend might be right, therefore we refused to avail ourselves of their escort. Their faces fell. They talked long and eagerly to the priest and our host.

The priest said to me, “Listen to what I say, but show no surprise or alarm. Let them not think I am telling you this. They are talking to our host about you. They say you are spies, and they are endeavouring to raise his suspicions of you; they mean you evil. O amici,” he said in his dog Latin, “multum est periculum per vos [Oh friends, you are in great danger].”

I now entered into an explanation of our journey. I showed that it was the most natural thing in the world that we had visited Montenegro; and soon disarmed any suspicion our host entertained; but the two Gussinians stuck to the point. The Bosnian turned fiercely to the Arnaut. “By Allah,” he said, “they are spies. We have twenty friends in the hills behind here; since they will not come with us, we will kill them here; now is the time.” I remember the very words in which. Father John, with pale face, translated this to us: “Ille homo,” he said, “dixit ad alium, Nunc est tempus intercidere illos homines [That man said to the other one: now is the time to kill those men].” The Arnaut spoke. He stood up in his hut with quiet dignity, and without showing the least excitement said, “These are my guests. You think that I will assist you to kill them. They are my friends; I will defend them. Now you are armed; we are not. Possibly you may kill us; but remember, it is nearly three hours to Gussinje. Men of our tribe have seen you approach; rest assured there are many rifles of the Klementi among the rocks. If you wish to go to Ali Bey, and not rot on the Klementi hill-sides, you had better go in peace.” The men looked at each other in silence; they knew the words of the Arnaut were true, and not being yet weary of existence, swallowed their coffee and sulkily left the hut. We took our revolvers and went outside, to see if any others were in sight. There were none; but on a rock that commanded an extensive view, we saw the erect form of a white-clad Arnaut, rifle in hand, scanning the ridge of the hill. The Klementis had evidently kept their eyes open. The probability is that these men had left Gussinje without the permission or cognizance of Ali Bey, and hoped with a fabricated message from the chieftain to tempt us to follow them to some spot, away from our friends the Klementis, where an ambush lay in wait for us. In their annoyance at our refusal to accompany them, they had betrayed their object.

No sooner was this adventure concluded than the occupants of the hut sat down and continued their coffee-drinking and smoking, as if nothing had happened.

Little events of this kind are every day occurrences in this wild country, and are thought nothing of.

The woman put her hand to her throat and drew it backwards and forwards, then laughed merrily, evidently chaffing us about the two separate risks we had so recently run of losing our heads.

As it was now evident that the people of Gussinje were not very anxious to entertain us, we saw there was nothing left but to return to Scutari. We were very disappointed; but what could we do?

We rode back with Father John to Seltz. The missionaries and the Lord Mayor rushed out. They were delighted to see us return in safety. “Ah Frater Edouardo, Frater Athol, come in. My poor friends, come in and sit down. How alarmed you must have been. Fear not; here you are safe.”

During dinner our story was repeated over and over again by the gesticulative little Father John, and great was the commiseration expressed for us by the kind-hearted fellows. The Lord Mayor became very warlike. “Had they hurt you, I would have taken a gun, gone to Gussinje, and shot Ali Bey—that devil!—myself,” he shouted.

While we sat round the fire after our meal, the door opened. “Nik Lek!” joyfully cried out our hosts, “Nik Leka safe! Praise be to the Lord.”

The celebrated Arnaut chieftain stalked in smiling, kissed each father on the cheek, shook us warmly by the hand, and sat down by the fire. He was very like his brother, a splendid specimen of a barbarian warrior; very handsome, with an expression that curiously combined great good-nature with a certain amount of latent ferocity.

He corroborated all we had heard about the feelings entertained towards us at Gussinje, and said, “You would not live long were you in that ferri—that hell over the mountains.” He himself had been obliged to escape, for his life was in danger among the fanatical inhabitants.

“They are like madmen,” he said, “now starving, desperate.”

He expressed intense hatred of the Turkis, as the Albanians call all Mohammedans. “Devils,” he said, “robbers. ‘Ku Turku vee kambet atu sdel baar’ (Where the Turk puts his foot, the grass grows not).”

Nik Leka has one vanity—he likes to be called a diplomatist. Talk to him on politics, the handsome warrior puts on a very knowing and wise expression.

Our conversation ran very much on politics tonight.

The fathers said, “These Arnauts have one wish. They know that an Albanian autonomy means Mussulman fanaticism, war, and Christians driven from the plain to starve in the mountains. What they wish is that you English would take the country. All the mountaineers discuss this and desire it. So too do the Christian townsmen. Do you think England will occupy Albania?”

This was a poser. I did not like to say England would never dream of doing such a thing, and that Austria would have a word to say in the matter, so merely pleaded ignorance as to the counsels of my country. Nik Leka nodded his head when my response was translated to him, smiled and winked at me, as much as to say, “Ah, these priests don’t understand politics. We diplomatists hold our tongues.”

Nik Leka told us that our old friend the bullying Bekir Kyochi, for so is spelt a name pronounced as Bektse Tchotché, was in Gussinje with the leaguesmen. “I should say the Scutarines will not weep much if the Montenegrins take his head,” I said. “Ah,” wisely replied the chieftain, “We say in Albania, ‘Ana e kece nuk schet’” (The worthless pot does not break).

Nik Leka, I found, considered that the discourse of a great diplomatist should be liberally interspersed with pithy saws and proverbs. He rolled them out with unction, and repeated each two or three times till he arrived at what he considered to be a properly emphatic delivery.

He told us he would accompany us back to Scutari; we should start early on the morrow. We were in luck; we had travelled hither with the boulim-bashi of the tribe, we were to return with its head man. We conversed till a very late hour. “A veritable Tower of Babel,” said Father John, with his stentorian roar. Latin, Albanian, Italian, Sclav, and English words were flying about the room, to the utter confusion of the Lord Mayor, who sat, looking very wise and sleepy, trying to make out what on earth it all meant.

I rose very high in the estimation of Nik Leka, when he heard that it was in Latin I conversed with the fathers. I was a greater diplomatist than ever in his eyes. He was a curious fellow. He would look at me thoughtfully, then suddenly jump up, shake me violently by the hand, and cry, “Mik, Mik” (You are my friend; you are my friend)—and then burst out laughing.

A very jovial evening we all spent over the log fire, drinking the fathers’ wine and raki.

[excerpt from E. F. Knight, Albania: a Narrative of Recent Travel (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1880), p. 200-250.]

TOP