| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

Two northern Albanian girls

(Photo: Alexandre Degrand,

1901).

1883

Arthur Evans:

Some Observations on the

Present State of DardaniaSir Arthur Evans (1851-1941), the British archaeologist known for his discovery in 1900-1903 of the Minoan ruins of Knossos on the island of Crete, was one of the rare nineteenth-century Englishmen to visit Kosova under Ottoman rule, or more properly, lack of rule. Travelling through Dardania (western Macedonia and Kosova) in 1883, after the Congress of Berlin (1878) and after the suppression of the Albanian League of Prizren (1881), he reported of a country with no functioning government or public order, a land "plunged into apparently hopeless anarchy." Evans' Balkans works have been republished recently in "Ancient Illyria: an Archaeological Exploration" (London: I.B.Tauris 2006) and "Albanian Letters: Nationalism, Independence and the Albanian League" (London: I.B. Tauris 2008).

The present distribution of vilayets in the Upper Albanian and Old Serbian region is altogether artificial and apparently unintelligible. Thus, while Uskup (Skoplje) and Pristina are included in the Vilayet of Kossova, the neighbouring and geographically inseparable districts of Tetovo (Kalkandelen) and Prisrend are placed under the distant Government of Monastir! This partitionment has very probably a military object, since in the case of an Albanian movement in the Shar ranges, the troops of two vilayets could be employed to crush it without any derangement of the normal distribution of forces. But it is also not impossibly due to a not unnatural dread an the part of the Porte of placing too large an Albanian district under the command of any one Pasha who might be tempted to play an ambitious game. Although the recent disturbances regarding the Montenegrin frontier question were local and mainly confined to the Catholic mountaineers of the Scodra district, they certainly have found an echo an this side of the Shar Dagh, and the Turkish authorities found it advisable to send several additional battalions to Gussinjé and other points. At the present moment the Albanian League may be said to be dormant, but there is ample evidence of the prolongation of the movement of which it was a symptom. It may be said with truth that in the Vilayet of Kossova and the neighbouring Old Dardanian districts, wherever the Albanian element preponderates Turkish authority exists, because it is not exercised. Even in the Mutessariflik of Uskup the most peaceable part of the country, no Turkish official dares venture into one of the Albanian mountain villages unsupported by a considerable troop. These Albanian mountaineers are well armed, mostly with Government Martini-Henrys, and they are continually tyrannizing over their Christian neighbours; but though they constitute an eventual menace to the Turkish Government, there is no apparent disposition and there has been no serious attempt to disarm them. The local Turkish officials, and this is a significant symptom, rather cultivate their goodwill. They (the Turks) speak with more than tolerance of the Albanian idea of forming a vassal State under the Sultan, and I have heard Turkish officers here openly execrate Dervish Pasha whose treacherous seizure of the Albanian Chiefs at Uskup put a temporary extinguisher on the "League." It must, moreover, be remembered that while Pashas, Mutessarifs, and Mudirs are perpetually changing, the Mahommedan religious officers sit en permanence in the divans of the konak and the local Medjliss and exercise a very real control over the administration. This Mahommedan religious influence is all on the side of the Albanian true believers, and any functionary who should ignore it sets in motion a whole machinery of intrigue ramifying to Stamboul.

The Albanians of this part are a rougher and more fanatical set than those of the Adriatic coastlands, and to give them complete local autonomy would be simple giving them free hand to tyrannize, even more than at present, over the industrious Christian population of the Dardanian lowlands. I use the term "Dardanian," because the districts of which I am speaking (those, namely, embraced in the present Kossova Vilayet and the northern strip of the Monastir Vilayet including Kalkandelen and Prisrend, and which lie between Albania proper and Serbia, answer nearly exactly to the old Illyrian Kingdom and later Roman Province of Dardania. Although, owing to the great Serbian exodus under Arsenius Tzernojevich, there has been a great Albanian migration into this Dardanian region during the last three centuries, it is certain that, at least in the southern districts, the Slavonic element, though less self-assertive, still largely preponderates. The rich plains about Uskup are tilled almost exclusively by Slavonian peasants (falsely called Bulgars - really, as their language shows, very pure-blood Serbs), and Serbian is the language of the market-place. Even about Prisrend, where the Albanian element is larger, a large number of the so-called Arnaouts still speak Serb, while at Novi-Bazar the Serbian language is overwhelmingly preponderant. In the mountain ranges alone can the population be fairly called Albanian.

My observations on the present occasion have been hitherto chiefly confined to the part of Dardania of which Uskup is the principal centre. It has, however, been pretty thoroughgoing, as I have had occasion to visit over fifty villages. This is by far the most tranquil and orderly region of the Kossova Vilayet, and I found it entirely free from any kind of brigandage. The nearest bands, at present, are in the neighbourhood of Prilip, and seem to be under the direction of the famous Nicko. They have no political significance, and are equally detestable to Turk and Christian. Nor could I find any trace of a political conspiracy or movement among the Rayah population of the Skoplje (Uskup) and neighbouring districts. Any such movement would, indeed, be hopeless and suicidal, as the Christian population, for the most part, inhabits the plain country and the lower ranges, and is kept in check by the armed Arnaouts of the surrounding highlands, as well as by the Turkish troops. Indeed, any such movement is, under present circumstances, so hopelessly out of the question, that I see no reason to doubt the statement of trustworthy natives, that the recent so-called conspiracy, by which the Turks have profited to seize many of the most intelligent and respected members of the community, existed only in the lying reports of Government spies and agents provocateurs.

As to this affair, the accounts that I have heard on all sides are most heartrending. Such was the brutality with which these wholesale arrests were conducted, that, in some cases, mere children were seized on political charges, and have since been as lost to their parents and relations as if the grave had swallowed them. To give a single instance: a boy of Uskup, Toder Mileo by name, aged 17, had written a letter to a friend in Bulgaria, in which he described some of the vexations to which the Christians here are subjected. This coming to the ears of the authorities, he was seized and carried off to Pristina, and, after being detained some time in prison there, was transported (with about 300 others) to Asia. All communication between the prisoners in Asia and their families has been cut off, and the only reports as to their condition that have reached their friends are due to a Serbian schoolmaster, who succeeded in escaping. It appears that several have already fallen victims to the rigour of their imprisonment, and whatever reports to the contrary may have been spread by the Turkish authorities, not a single individual has hitherto been liberated. So far, indeed, is this from being the case, that the threat of further arrests is now continually made use of as a means of extortion. The chief places of detention seem to be Trebizond, Diarbekir, Konjeh, and Acre, and several are still imprisoned in Salonica. Of the two chief informers, one is a Vlach of Pristina, who has since made himself Mahommedan, and swaggers about as "Omar Effendi." He has been decorated by the Sultan, and has just received a sum of money to make a pilgrimage to Mecca. The other is no less a personage than the Fanariote Archbishop of Skoplje, Paysios - for the Porte still appoints here its "spiritual Pashas."

Were there any reasonable prospect of a successful uprising, the motives for it are certainly very strong. Since the conclusion of the Treaty of Berlin, the Christian population of Dardania has been tyrannized over as it never has been before within the memory of man. No words of mine can sufficiently describe the abject slavery in which the peasantry of this region is at present held. In village after village that I visited, wherever the inhabitants had an opportunity of speaking to me out of official hearing, I heard everywhere the same tale; and all to which I myself was a witness, corroborated its truth. The zaptiehs, the visible agents of the Turkish Government, are practically omnipotent. On the slightest provocation the peasants are beaten or hauled off to the filthy dungeons of Velese, Uskup, or Pristina. The Turkish functionaries live at the villagers expense, and the way in which food, &c., is thus "requisitioned" would lead any one suddenly planted here to imagine that the country was in the military occupation of some invader. The most crying grievance, however, is the forced labour, or "angaria," which is exacted here with merciless brutality. Some new military magazines and a new road to Kumanova being in course of construction, the "angaria" is just now exceptionally heavy, and I found villages the male population of which has had to undergo seven entire weeks of forced labour during the last four months. The value of hired labour here is about 6 to 10 piastres per diem, so that the money value of the labour thus exacted represents at a moderate estimate 294 piastres a-head, or nearly 900 piastres in the year. But the manner of enforcing this "angaria" considerably adds to its oppressiveness. No consideration is shown for the necessities of field labour, and men are literally beaten in from the plough or the harvest field. In most villages here the "métayer" system prevails - half the produce being paid to the Turkish landholder; in some of the mountain villages, however, the land is the peasant's own. It is, however, saddled with a land tax (varying according to the estimated value of each "dulum"), known as the "vergija," in addition to the payment of the Sultan's tithe. A poll tax of from 40 to 60 piastres (or more) is paid by every Rayah man and male child over 10 years of age, and is still known as the "haratch." The taxation itself, I imagine, is not so oppressive as the method of levying it and adding to it by irregular means. As a sample of the wholesale way in which the peasantry are "requisitioned," I may mention that on a market day, when all means of transport were especially needful to the villagers, I saw no less than twenty waggons with their drivers impressed by the Turks in a single large Bulgarian village.

In a large number of villages I found the churches fallen to ruin or non-existent altogether, and to my inquiries why they were not built or restored, I received the never failing reply that their Turkish (i.e., Mahommedan) neighbours would not allow it. This intolerance is not to be set down to the higher Turkish authorities, but to the local fanatics, whom, however, it is no part of their policy to thwart. In the matter of schools, however, these higher authorities seem only too prone to act as the champions of obscurantism. It is now only a few weeks since they made a raid on the Bulgarian school at Uskup, and seized and confiscated all the school books relating to history or geography. Henceforth the masters have had to content themselves with Church books. Everywhere the Christian schoolmaster is regarded as a suspected person, and with no class of the population is the dread of violence so constantly present.

Although a large part of the plain is vacouf of the mosques of Uskup, the authorities deny that the Christian churches or monasteries can hold lands in their own name. On the death of the Hegumen of the Monastery of Boujanski a few weeks since, the authorities at Uskup profited by the occurrence to seize and confiscate the lands of the monastery. The protests of the Orthodox community were unavailing, and, finally, to save the monastery from entire destitution, they had to repurchase the lands. The law of the land is still the Mahommedan religious law, and the complaints as to the non-admittance of Christian evidence are universal. As to the sentiments of the Christian population, I cannot do better than reproduce the words of a village Elder: "There is no justice for us. We toil day and night, but the Turks take all our earnings, and even then they will not let us alone. We can't send our children to fetch water at the fountain but they are stoned or otherwise ill-treated. I tell you we will take off our caps to any king who comes to us. The yoke ("zulum") is more than we can bear."

The preceding observations on the present condition of Dardania have been mainly confined to the district south of the Shar range, and of which Skopia (Uskup) forms the principal centre. The remaining part of the country - the Kossovo district proper, the plain of Metochia, including the towns of Prisrend, Djakova, and Ipek (Pec) - is at present in a state of almost complete anarchy, and requires separate consideration; while in the more southern tract, for good or evil, Turkish government may still be said to exist, and while in the Mutessariflik of Uskup, at any rate, praiseworthy efforts are made to check non-official robbery and murder, I can only describe the state of things north of the Shar as a reign of terror. It is only at Pristina itself, the seat of the Vali Mitrovitza, and the immediate neighbourhood of the Macedonia Railway, that Turkish government can be said to be really existent. The exploration of this region is at present a matter of considerable risk, and though, with adequate precautions, it is possible for an Englishman (our nationality being favourably regarded by the Albanians) to visit some of the towns, many of the country districts are at the present moment as inaccessible as if they were in Central Africa. Under these circumstances, anything like a complete view of the state of the country is out of the question, and I must content myself with samples derived from a journey through some of the most interesting districts.

The day I arrived at Prisrend there were three cases of robbery with violence and murder in the immediate vicinity. From one village eighty sheep, together with the dogs and shepherds, were carried off by Arnaouts from Ljuma. A drove of horses was attacked on the road, three of the drivers more or less severely wounded, one of the marauders being killed. A Turk was waylaid and killed also by Arnaouts, with five desperate gashes. In no case were the offenders brought to justice.

I found the Christian population, especially the Orthodox Serbs, in the most abject state of misery and degradation. The Serb seminary for teachers still exists, as it is under the direct protection and in the immediate vicinity of the Russian Consulate. The boys' and girls' school, however, is closed, as the schoolmaster was seized and transported to Asia, while his wife, who taught the girls, fled to Serbia, and the terrorism is such that no one dares take their place.

The state of things in the Serb villages about is worse still. Whereas in the Uskup district it is at any rate the Government, or its officials, who demand forced labour and requisitions, here the Arnaouts, without any official commission, exact this "angaria," as it is called, for themselves. A few days since, an Arnaout of the village of Kabaš ordered a Serb of the village of Koriš to work in his field for him; on the Serb not coming, the Arnaout hunted him down and murdered him. As the name and abode of the malefactor were perfectly well known, the villagers ventured to complain to "the authorities" at Prisrend. Zaptiehs were accordingly sent, but instead of going to Kabaš at all, they betook themselves to the Serbian village; lived at free-quarters on the villagers for two or three days, and then returned to the konak with the usual report that the murderer had managed to escape. In the case of a similar recent murder in the village of Kouša by the Arnaout Bairaktar of the neighbouring village of Malahoca, zaptiehs were not even sent, and this worthy has been since allowed to occupy himself with the task of levying black mail of about 200 piastres a-head on various Christians of the neighbourhood. Old men say here that the "zulum" (Turkish yoke) has never been so bad as now. Cases of beating are of almost daily occurrence, and the Arnaouts settle on the Christian villages in gangs, and live at free-quarters for days at a time. The Government does nothing, and is, in fact, inspired and directed by the worst of the local fanatics. Christian evidence is not accepted, and the only code recognized is the Mahommedan sacred law.

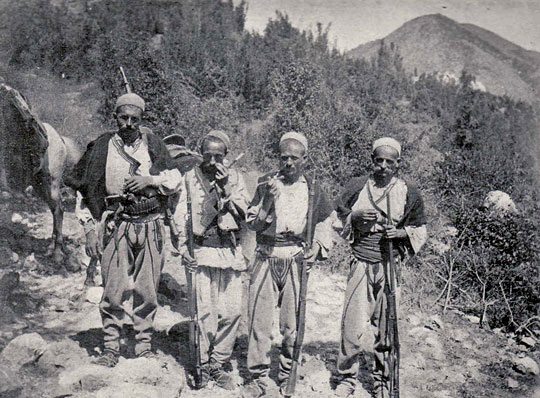

Tribesmen from Mirdita

(Photo: Alexandre Degrand,

1901 )

The condition of the Catholic Albanians here, who are more or less under the aegis of Austria, is distinctly better than that of the Pravoslaves, but they still have to suffer endless vexations; and such is the present reckless temper of the Arnaout population here, that the Austrian Vice-Consul was himself shot at last autumn in the streets of Prisrend. Within the last few days, the chief entrance to the Roman Catholic churchyard here had been walled up by the native fanatics, acting through the Turkish authorities. The church bell cannot be rung. The women have to go about veiled, as if they were Mahommedans. Twenty Mirdites have recently been seized and imprisoned here for refusing to pay the military tax, the right of military service in lieu of this tax being, as is well known, one of their oldest privileges. Although the right of the Catholic Albanians to possess arms has hitherto been acknowledged, a Catholic here who had bought a gun of Austrian fabric was seized and thrown into prison, and has not since been allowed either to see his friends or to receive food or money from them. Don Marco (the hero of the well-known episode of the transportation of the Albanian Crypto-Catholics some thirty years ago) is at present the Catholic priest here, and, considering the martyrdom which he has himself endured, his opinion may be worth quoting: "Since the Treaty of Berlin, the state of the Christian population here has been worse than I can ever remember it. Bad, however, as the condition of the Catholics is, that of the Greeks (i.e., Orthodox Serbs) is infinitely worse. The savagery with which they are treated is fearful; they are beaten and murdered with perfect impunity, and the forced labour that they have to undergo at the hands of the Arnaouts passes belief.

At Djakova the state of public security was such that the Mudir dared not allow us (myself and my wife) to show ourselves in the street; and it was only, subsequently, through the intercession of a local Aga, that we were allowed to visit a part of the bazaar. Two days before, a murder had been committed in the principal street in the presence of Turkish zaptiehs, who discreetly turned their backs and walked away. The Christians here are terrorized over even worse than at Prisrend. As a sample of the ferocious spirit of the inhabitants, I may mention an incident, related to me on good authority, that occurred here a few weeks since. A Turk who had an illicit connection with a girl, falsely accused an old Christian man (of 65) of being the real culprit. The man was not even brought to trial; the native fanatics set upon him, and literally hacked him to death. After this, his body was impaled, and the impaled corpse was finally used by the Arnaouts as a butt for their rifles. So far from molesting ourselves, however, many of the Arnaout Notables came to visit us and our quarters, and showed themselves friendly, though excessively curious.

The Old Serbian monastery of Decani (the church of which is the most valuable art monument of the whole interior of the Balkan Peninsula) we found in a most pitiable condition. It is impossible to walk a hundred yards from the walled inclosure of the monastery without an armed guard. The wild Arnaouts are continually settling on the monks and living at free-quarters; only last year they burnt one of the out-buildings of the monastery, and fired volley after volley into the interior; one of the monks had had his hair and beard cut off three times, and had once literally had the knife at his throat. The most recent extortion to which they have been subjected by the Albanians is a system of forced "loans," never repaid. The peculiar significance of the state of things here lies in the fact that the monastery is Imperial vacouf, protected and privileged by the authority of innumerable Firmans.

In the Ipek (Pec) district the state of things is, if possible, worse than that of Djakova. Ali Pasha, of Gussinjé, is the Governor here, civil and military, but though powerful enough in his native town, he is here a mere puppet in the hands of the worst fanatics. He allowed us to visit the bazaar, but gave us a guard of eight armed Albanians while we did so, and even then the appearance of "Europeans" in the streets caused such a ferment that the Pasha dared not allow us to re-enter the Tcharshi, or even to visit the Serbian school (though we succeeded in seeing that when subsequently leaving the town). The Patriarshia or Monastery (the former seat of the Serbian Patriarchs of Ipek before the exodus of Arsenius Tchernojevich) we found in much the same state as that of Decani. The state of terrorism is such that three-fourths of the normal congregation dare not attend the church, the Christians being set on, shot at, and beaten by the Arnaouts on their way thither. The doors of the monastery itself are perfectly riddled with bullet-holes, and more than one murder has been committed in its immediate precincts. There are several house-fathers who dare not so much as venture outside their own yards. In this district alone there have been over 150 murders since the Treaty of Berlin, some of them of mere children. I have been supplied with data regarding ninety-two cases, and I am assured that in no single instance has the murderer met with punishment from the authorities. During the days I was at Ipek, a great murder of a Serb occurred in the village of Gorazdova, where there have been recently two previous cases, and in the village of Trebovica there was a case of abduction of a characteristic kind. A Turk (Arnaout) persuaded a young Christian girl of 16 or 17 to marry him and turn Mahommedan. The girl's parents refused their consent. The authorities interfered so far as to seize the mother and convey her to the prison at Ipek (where she was when I left), while the Arnaout carried off her daughter. There have been five or six similar cases, and one of the leading Arnaouts here commits with impunity outrages of a still grosser nature.

From what I heard, there can be no room for doubt that there is an organized attempt by repeated acts of violence and robbery to drive out the whole Orthodox Serbian population that still exists in this nahié. Those who know the country best informed me that the Arnaouts, wild and lawless as they are, would not behave as they have been behaving unless they had got the wink to do so from those in power. The chief instigator of the worst outrages is universally recognized to be Mullazeg, a very wealthy Arnaout, who, with a knot of kindred spirits, has the Pasha and the Local Government entirely under his thumb. The oppression being more than can be borne, the Christian population are at present taking to flight, whole villages at a time, and making their way towards the Serbian frontier. The greater part of the inhabitants of the following villages have already fled: Budisavac, Ruhat, Gjurgjevich, Plaoljani, Sverk, Kijevo, Osojani, Zablaci, Kruševo, Zac, Josanica, Novoselo, Ottomanci, Dolac, Drsnik, Radulovci, Koš, Naglavka, Draguljeva, Istok, Gjurakovac, Nabržje, and a part of the inhabitants of Gorazdovac. The refugees have mostly reached the Serbian frontier: all hope to be able to return whenever this tyranny is overpast.

One result of the lawless defiance of all authority on the part of the Arnaouts is that the tax farmers, who have to drop a certain sum, and who often cannot get their due from the Albanian part of the population, make the unfortunate Serb villagers pay for their oppressors as well as themselves. The "vergija," or land tax, especially, is frequently demanded twice or three times over, and, as no receipt is given, the villagers have no security against these extortionate demands. In committing this extortion, the tax gatherers find every assistance from the authorities (who are entirely in the Arnaout interest), and several Christians are at this moment in prison at Ipek for refusing or being unable to pay the same tax twice or it may be three times over.

The Serb school at Ipek is not interfered with, though the schoolmaster lives in peril of his life. The Ottoman soldiers and officers in garrison here, although not used by the Porte as an instrument of order, are well disciplined, and their presence is rather welcome to the Christian inhabitants. On the other hand, there is abundant evidence of the close relations subsisting between some of the most abandoned Albanian ruffians and the Palace at Stamboul. Both here and at Prisrend, however, there are many worthy Mahommedans who would welcome any change that should put a stop to the present frightful anarchy.

In the neighbouring district of Kolašine I learnt that the same anarchic state prevailed, to which I was a witness, these two years since. The Christians are murdered and plundered there without redress, or the possibility of redress, as in the Ipek district.

On my way from Ipek to Mitrovitza I passed the night in the small Serbian village of Banja. For six hours the road ran across a fertile and well-watered and formerly thickly-populated plain, which has been reduced to a desert entirely void of habitation or cultivation. At Banja I found the villagers debating whether they should fly the country at once. The whole neighbourhood is a scene of horrors. Three days since, a young Serb, Simo Lazaric, of the neighbouring village of Maidax, was bathing in the tepid spring from which Banja derives its name, when he was shot in cold blood and out of pure wantonness by an Arnaout from Derviševic. The day before, in the village of Djakorice, which is also near here, another young fellow, Josif Patakovic (aet. 20), was shot in the same way, and another Serb badly wounded. The church is in ruins. The inhabitants spent six months in trying to restore it, but the "Turks" destroyed it again. The school is also in ruins, and no schoolmaster dare stay. One old cripple asked me with tremulous eagerness if there was any chance of a war.

At Vucitrn, I found the school closed, as the schoolmaster is in prison; it is believed at Salonica; and the Serbian Pope here, Danco, has been in prison two years. At Janjevo, where the great bulk of the population is Catholic, the people had not so much to complain of bodily violence and murder as of illegal extortion. Here, again, taxes are demanded as much as three times over, for the benefit of the surrounding Arnaouts, who, to a great extent, go scot-free. The Crypto-Catholics, of whom there are large numbers in the Karadagh about Gilan, are perpetually trying to get some assurance of protection for the free exercise of their belief; the Gilan "Turks," with the connivance and sympathy of the local Governor, declaring their intention to murder them and burn their villages should they openly profess Catholicism. The Franciscans at Janjevo have again and again appealed to the Porte to secure them the requisite protection, but the Porte has again and again put them off. The hold of the fanatical Mussulman party on the Palace is too strong for the Porte to act in the matter, even if it be liberally inclined. The Catholic monks here, as at Prisrend, corroborated the fact that the Pravoslaves are infinitely worse treated than the "Latins." And the news, just arrived of a horrible murder of two Serbs, one shot and the other hung to a tree by Arnaouts in a village near Gilan, sufficiently illustrates the fact.

In considering possible remedies to the present state of things in these regions, the following observations suggest themselves:

1.

The first, and most crying necessity, and about this I found an universal agreement of opinion, is a thorough-going disarmament of the Arnaouts. Those well acquainted with the country assured me that this might be effected with far greater ease than I was at first inclined to suppose. In the presence of resolute acts of authority, the Arnaout shows a submissiveness astonishing to those who know him in his fiercer moments. The whole history of the "Albanian League" shows, indeed, how easily he may be guided.

On the other hand, it is extremely doubtful whether the Turkish Government can be induced to put forth such an exercise of authority. The intimate relations between many of the Chiefs and the Palace are notorious, and the greater part of these Arnaout desperadoes are armed with Turkish Government Martinis.

2.

No settled Government can be hoped for while the worst malefactors are allowed to swagger about unpunished. The execution of a score or so of the worst characters, and those not the humbler instruments, but the practical Governors of the country - men like Mullazeg and his compeers - is at least as necessary as disarmament. But these leading offenders are precisely those who have most influence at Stamboul.

3.

I observe that the Franciscans, who take their cue from Austria, are all in favour of some kind of Albanian Principality. Whether such has been the Austrian view or not of course I have no means of knowing; but if it has been so in the past, it is sufficiently evident that the growth of Slavonic influence in Austria will make it henceforth impossible for that Power to place the south Slavonic holy places, viz., Decani and Ipek - the goals of Orthodox ambition from the Drave to the Macedonian borders - in Albanian keeping.

At the present moment, although the Albanians have everywhere the upper hand, the balance between the numbers of the Serb and Albanian population in the Kossova and Metochia district is, as far as I can judge, pretty even. Whenever settled government supervenes, this will be no longer the case. The deserted plains will be again tilled, not by Albanian, but by Slavonic colonists. The tide of Slavonic colonization is already flowing up the Morava Valley into the part of Arnaoutluk acquired by Serbia at Berlin. The re-Slavonization of the Kossova and Metochia plains is only a question of time. By converting them into a desert, the Turks have really been playing the Serbian game.

4.

Apart from all economic considerations, and having solely regard to the tranquillization of the country, the importance of securing railway communication with the great plain of Metochia (at present the scene of the worst terrorism) deserves the most serious attention. I learn that the trace of a line leading from Scodra (Scutari d'Albania) across the Albanian Alps to the neighbourhood of Prisrend and Djakova has already been made, and presents serious difficulties only at one point. This line of communication is really of the highest eventual economic importance, as it would give the plains and highlands of Dardania - the chief mineral treasury of the peninsula - direct access to the Adriatic port. It would also find a continuation in the Morava Valley line to Nisch, &c., and would coincide with a great line of Roman road, undertaken primarily as an engine of pacification and civilization amongst the wild forefathers of the Arnaouts.

The comparative security for life and property in the immediate neighbourhood of the existing line from Mitrovitza shows the great desirability of railway communication with the districts at present plunged in apparently hopeless anarchy.

5.

The abolition of forced labour ("angaria") and "requisitioning" would remove one of thc principal grievances of the rayahs. It is, however, about the last thing that the Turkish authorities will consent to. Were any local Governor to attempt to carry out such a reform and tax Mahommedan and Christian impartially, he would be at once intrigued against at Stamboul. As it is, the forced labour is practically a tax levied in the country districts where the Christians are in a majority (and almost exclusively on the Christian villagers) for the benefit of the towns where the "Turks" are in a majority.

Uskup (Skopia), August 11, 1883

[from: Some Observations an the present state of Dardania, or Turkish Serbia (including the Vilayet of Kossova und part of the Vilayet of Monastir) by Mr. A. Evans. First published in: Bejtullah D. Destani (ed.), Albania & Kosovo: Political and Ethnic Boundaries, 1867-1946. Documents and Maps. Slough: Archive Editions, 1999, p. 257 265.]

TOP