| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

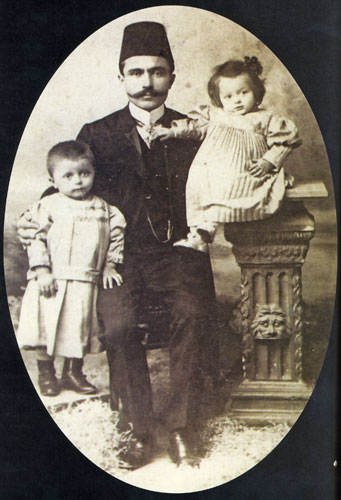

Faïk Bey Konitza, 1905

1899

Faïk Bey Konitza:

Memoir on the Albanian

National MovementFaïk bey Konitza (1875-1942) was one of the great figures of Albanian intellectual culture in the early decades of the twentieth century and was no doubt the first Albanian whom one might consider to have been a real European. Konitza was born on 15 March 1875 in the now village of Konitsa in the Pindus mountains in northern Greece, not far from the present Albanian border. After elementary schooling in Turkish in his native village, he studied at the Jesuit Saverian College in Shkodra and at the French-language Imperial Galata secondary school in Constantinople. In 1890, at the age of fifteen, he was sent to study in France where he spent the next seven years. After graduation from the University of Dijon, in Romance philology in 1895, he moved to Paris for two years where he studied mediaeval French, Latin and Greek at the Collège de France. He finished his studies at Harvard University in the United States, although little is known of this period of his life. As a result of his highly varied educational background, he was fluent in Albanian, Turkish, Italian, French, German, and English. It was during his stay in France that he began to take an interest in his native language and his country's history and literature, and to write articles on Albania for a French newspaper. In September 1897 he moved to Brussels, where at the age of twenty-two he founded the periodical “Albania,” which was soon to become the most important organ of the Albanian press at the turn of the century. He moved to London in 1902 and continued to publish the journal there until 1909. It was in London that Konitza made friends with the noted French poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), who stayed with Konitza at the latter’s Chinford home in 1903 and 1904. In the New World, Konitza became editor of the Boston Albanian-language newspaper “Dielli” (The Sun), which was founded by Fan Noli in 1909. “Dielli” was the organ of the important Pan-Albanian “Vatra” (The Hearth) federation of Boston, of which Konitza became general secretary in 1912. In 1912 he travelled to London on behalf of the “Vatra” federation to defend Albania's interests at the Conference of Ambassadors which was to consider recognition of the fledgling Albanian state. In 1921, back in the United States, Faik Konitza was elected president of the “Vatra” federation in Boston and resumed editing the newspaper “Dielli” there, in which he now had his own column, “Shtylla e Konitzës” (Konitza's Column). In the summer of 1926, he was appointed Albanian ambassador to the United States by the dictator Ahmet Zogu (1895-1961), a post he held until the Italian invasion of his country over Easter 1939. He died in Washington on 15 December 1942 and was buried in Forest Hills cemetery in Boston. After the fall of the Communist dictatorship, his remains were transferred to Tirana and interred in a park at the edge of the city.

Konitza’s “Mémoire sur le Mouvement National Albanais” (Memorandum on the Albanian National Movement), was drafted in Brussels in January 1899 for the Austro-Hungarian authorities in Vienna in order to inform them and get support for the Albanian cause. The memorandum, by which Konitza also no doubt hoped to get an Austrian subsidy for the publication of his journal “Albania,” provides a sincere, though personal assessment of the Albanian national movement in the final decades of the nineteenth century.

MEMOIR ON THE ALBANIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT

First Part (up to 1877)I

Until 1877, very few Albanians had any idea that theirs should or could be a written language. It is true that in Northern Albania, and above all in Scutari, a number of merchants did make use of the Albanian language in corresponding with each other; and the Roman Office of Propaganda had published a number of religious books in Albanian, But this initiative did not pass beyond its own narrow scope, and was not related to any national idea.

In Southern Albania, a similar initiative had been more successful. In 1827 the four Gospels had appeared in Albanian, in Greek script, and in a little time this book was in all Christian homes. The first edition had a print run of several thousands, and a second was issued in Athens in 1858.

II

Around the same time, an Albanian from Vithkuq near Korça, called Naum Veqilharxhi, published an Albanian alphabet in Bucharest; and, back in Albania, sought to give a practical impetus to his initiative by setting up a school and propagating an inclination towards the national language; but, on being denounced to the religious authorities, he was, as all Albanians of the time thought, poisoned on the orders of the Patriarchate in Constantinople.

III

Another event proved happier for the Albanian language. About the middle of the century, J. Georg von Hahn, Austrian Consul in Janina, wanting to learn Albanian, found two teachers: one called Apostoli, a surgeon by profession, and the other Kristoforidhi. Then he set himself the task of travelling around the country to collect folk songs and stories. This interest shown by a foreigner in their national language impressed a number of Albanians, who resolved to cultivate it themselves.

IV

Further, one of Hahn’s two teachers, Kristoforidhi, had already undertaken the collection of all Albanian words, in order to prepare a complete dictionary. Having been engaged by the London Bible Society in 1871, he published the next year an alphabet, a grammar, an abridged religious history, and so on.

However, the Greek Patriarchate was on the lookout for a suitable opportunity to uproot the Albanian language from the heart of the Albanian Orthodox, once and for all. One Sunday it organised a proclamation in all the churches that the Albanian language was the language of Protestants, Catholics, freemasons and atheists (since for the Orthodox these are interchangeable terms) and that in consequence one must take care not to handle the various Albanian books which were being spread around. From this time dates the stubborn and ineradicable hatred fostered for the national language by Orthodox Albanians - who are without doubt the most fanatical, stubborn, and least intelligent grouping in Albania.

From this angle, Kristoforidhi’s books were a misfortune. But there was another side to it. Many Muslim Albanians were happy to buy these books, and I have seen them in many houses of Southern Albania. In any case, even if this opportunity had not presented itself, the Patriarchate would have looked for and found another.

V

An influence similar to Hahn’s was exercised by A. Dozon, the French Consul. Nothing surprised the Albanians who visited him, so much as to see this foreigner writing their national language. It set them thinking.

VI

In brief, until 1877 a taste for the national language existed only in embryo and, above all, among people of a certain distinction. For despite the various revolts - notably against the Constitution of 1830 and those of 1854 and 1863 against obligatory military service, revolts concerned with a degree of autonomy - the question of the national language had not been raised in any serious fashion. One must move on to 1880 to find it so raised.

Second Part (1877 to 1884)

I

At this period an Albanian called Tahsin lived in Janina. He was a very erudite man, who had lived for a long time in the company of scholars and men of letters in Paris: it was his affectation always to wear a turban. In 1877 he found himself in Janina and, having had an Albanian alphabet printed in Turkish script, he distributed it widely throughout Albania. He was allowed to go on doing this for some time, before being arrested and sent to Constantinople.

II

Tahsin’s initiative was significant: it corresponded to a feeling of disquiet that Albanians as a whole began to experience. There was talk of the cession of Southern Albania to Greece; and as this rumour persisted, several intelligent Albanians realised that they had a language and national interests to defend.

A conference of Albanian notables was held in Constantinople, and there a decision was taken to send a number of delegates into Albania, to prepare people for an eventual uprising. One of these delegates, Abdul Bey, realised that a majority of Albanians of the south could be won over if one could persuade the ‘babas’ or ‘Bektashi fathers’, the dominant religion or sect in the Tosk areas. It should be understood that these ‘babas’, formerly violently persecuted by the Turkish government, and even now enjoying only a very limited freedom, had always looked for a chance of liberating themselves. So Abdul Bey made visits to all their ‘tekkes’ and (thanks to the co-operation of the Chief Baba, Alush bey Frasheri, a kind of archbishop of this religion) had little difficulty persuading them to use their influence on the notables in favour of an eventual rising to achieve autonomy.

III

Meanwhile, events were hurrying forward. The Albanians kept the impetus going, and continued holding assemblies in Constantinople. The Sultan, suspicious at first, looked with favour on the Albanians until events took an unpleasant turn in Turkey. Thus Abdul Bey was sent once more into Albania, this time by the Sultan, to encourage (and also, some people said, to keep an eye on) the growing League, of which Prenk Bib Doda and Hodo Bey were the moving spirits.

IV

I do not feel I need to talk about these events, because they are known and have been described in a good many books. But I will say a few words about one or two important facts which are not known:

i) The League of Southern Albania, led by Abdul Bey and Mehmet Ali Bey Vrioni (as that of the North by Bib Doda and Hodo Bey) sent to all the southern beys the order to keep themselves and their people under arms, ready to set out at the lightest signal; and that if they refused, their houses would be burned, their goods confiscated, and themselves and all the members of their family executed; and if they did not preserve absolute security about this order, the League, which had undercover members everywhere, would be fully informed of any treachery. This fact is certainly correct; for I remember that my father, who was alive then, had brought together from all around a great number of Albanians, and got ready to leave, on the day to be indicated, to carry out the order he had been given, which was to arrest the Turkish deputy governor, to occupy and fortify the square at Konica, to visit all the houses of pro-Greeks to secure any arms they might possess, and to proclaim the new government. After which, leaving enough men to give effect to the new authority, he was to go with his followers to a designated point, there to meet up with the other beys, who would have carried out a similar order in their own respective areas.

But private individuals, without official backing, cannot with impunity give orders to people of whom the majority either do not understand, or do not share, their opinions. So the methods of the League provoked extreme irritation among most Albanians.

ii) From day to day Abdul Bey became more authoritarian and more peremptory. He had gone to Libohova to demand 100,000 Turkish liras from Malik Pasha for the League, and when Malik Pasha promised him only 10,000, Abdul Bey threatened him, and said that when the revolution broke ont, he would return to kill him and confiscate everything he had. Then the Albanians, who are far and away the most suspicious people on earth, began to ask themselves whether Abdul Bey did not have the ambition of making himself king. An amusing suspicion turned into a certainty for them: ‘Yes, he did want to become king!’ Irritation simply grew. ‘And who is it who wants to become king? A bey, and an ‘unbreeched’ bey at that, Abdul Dume-Kerozi’ (that is to say, Abdul of the Scabby Dume family). So the leading Albanians came to an agreement to countermand all Abdul Bey’s projects, and from then on all the League’s projects for action were a pitiable failure. It must be added that the suspicions against Abdul Bey seemed to be confirmed by what followed. There turned out in fact to be another claimant to the imaginary throne, Murad Bey Toptani. To prevent rivalry (so they say) Abdul Bey gave his niece in marriage to Murad. Hence alliance and peace were made between the rival houses.

V

Meanwhile, as these events were going forward in Albania, the Albanians of Constantinople, to give greater strength and staying power to their meetings, founded in 1879 a society which they called ‘Drita’ (Light). They immediately published the rules of the society in a widely-distributed brochure, and a reading book with an alphabet adopted by them.

All these publications were authorised by the Turkish government. The ‘Drita’ Society, foreseeing the end of the League, determined to survive and carry on its work.

VI

Contemporaneous with the ‘Drita’ Society at Constantinople, another society, ‘The Voice of Albania’, was founded at Athens by Koulourioti. Koulourioti occupies one of the most important places in the Albanian movement. Born in Greece, and orphaned at an early age, he was sent by the Greek Protestant Mission to America, where he distinguished himself in his college studies; then, turning to business, he made a large fortune in a few years. Back in Greece, he formed a committee, then an Albanian and Greek paper, ‘The Voice of Albania’, both of them frankly anti-Greek. He was accordingly persecuted everywhere: in restaurants and cafes, in shops where people refused to sell to him. He was blackguarded and stoned in the streets. In 1882, this Albanian patriot went to Albania to distribute nationalist books he had printed.

But the Greek consul had him arrested at Gjinokaster and he was sent back to Athens as a prisoner. All the same, he went on with his propaganda for several years; then he died after, it was said, having been poisoned. Koulourioti exercised an enormous influence. He inspired generous ideas, awoke the conscience of many, and produced the first example of an Albanian newspaper.

VII

Fortunately this example was copied. In 1884, the Constantinople ‘Drita’ received from the Sultan firman permission to publish an Albanian newspaper. This appeared, in fact, under the same name as that of the society, and appeared until 1885 (12 issues). Then the Turkish government, seeing that the paper was widely read, took umbrage and began to make difficulties. It was decided to transfer both the paper and the society’s headquarters abroad. Bucharest was chosen, and one Vreto was sent there on behalf of the Albanians of Constantinople.

VIII

Something then happened to the society’s advantage. A very rich Albanian merchant, Nicolas Naço, had been living in Egypt for 30 years. Naço had a 15-year-old nephew whom he had left, during a short absence, at the Greek Consulate in Alexandria, where a friend of his, Krokhlihas, was Consul. Krokhlihas seemingly failed to comport himself morally, and Naço’s nephew killed him with his revolver. Implicated in the case as an accomplice, Naço was sent to Greece with his nephew, having become naturalised as a Greek subject in Egypt. One must be aware of this detail to understand certain subsequent facts.

Nikolla Naço

In Athens, Naço came to know Koulourioti, who persuaded him to work for a revival of Albanian national feeling. Acquitted by the court, Naço then left for Bucharest; going by way of Albania, where he did some propagandising.

IX

At Bucharest, Naço found the ‘Drita’ Society, only recently established, already wholly in a state of disintegration. Parties had been created. One or two authors had sent manuscripts of books for publication; but the Albanians of Bucharest, notwithstanding the statutes of their society, would have nothing to do with them. They said: ‘the manuscripts must be sent to Germany, where there are a number of Albanologists, to judge if they are worth printing. ‘ In brief, the general feeling was that they must make a pretence of keeping the ‘committee’ in existence, otherwise the patriots would form one in earnest; that the Orthodox, even when Albanian speakers, would never wholeheartedly undertake any activity prejudicial to Greek interests and those of Russia; that the ‘Turkish’ Albanians (that is, the Muslims) were insincere allies, who called for a pretence of national unity in order to reduce all the Orthodox again to a state of serfdom; and that, in sum, if it were necessary to call oneself Albanian, no opportunity should be lost to work behind the scenes in favour of religion rather than the national movement.

These things were said again and again at both public and private assemblies. And they corresponded so closely to the general feeling that it was decided to put up for public sale the type and the printing equipment the society had previously bought to publish at less expense all sorts of books.

X

A number of day-to-day happenings were to prove for certain the hostility of these Orthodox for their nationality. It was in this state of mind that a general assembly was convoked in 1885 at the instance of Naço, who had gained for himself a number of followers. It was in this assembly that one Constantin Efthimi, a very rich Albanian and president of the society, spoke with great heat against the national movement and in favour of Russia, so for that sole response, Naço discharged a pistol shot at him.

Third Part (1885 to 1895)

I

Thus so far no serious attempt had been made to spread the idea of national identity in Albania. Initiatives of only short duration, and in consequence of little significance, had been made; and only one decisive step had been taken - the creation of an overall society, which was to bring together all the efforts, which was to work uninterruptedly, publishing and publicising books and awakening the nation. But this effort collapsed as soon as it was born!

Naço, acquitted unanimously by a patriotic Romanian jury, hostile to Russian influence, set to work again. But he found very few supporters of his propaganda. This was because during his case, the pro-Slav party had reformed and consolidated itself to achieve cohesion and start to grow. The head of this party was, and remains, an Albanian, Hercule Duro, both rich and very influential among the Albanians. Other parties were formed, notably a Greek party under the direction of another well-to-do Albanian, Gavril Pema. But it must be noted, as we shall see further on, that these are mere subdivisions, and that all these parties are agreed on this essential point: that is, that Albania must come under an Orthodox power, never mind whether large or small, and that all propaganda must be directed to this end.

Accordingly meetings were arranged here and there. What exasperated the Greek-Slav party above all was that Naço showed himself as favouring Turkey; and that on the Sultan’s birthday he went with two hundred Albanians to give a demonstration of loyalty in front of the Turkish Legation.

II

The ‘Drita’ society, reconstituted by Naço, began to print and distribute Albanian books. He also set up a Propaganda School where young people from Albania received a speedy and substantial briefing and returned to Albania.

One thing, though, harmed Naço and gave the Greek-Slav side a field day: that intelligent and experienced as he was, and knowing six languages, he had learned all he knew by listening and observing, for he had not had even elementary instruction, and he only knew more or less correctly how to read and write. His opponents, although they knew little more than he did, brought this ignorance to light, and nothing discouraged the Albanians more than to tell them they were in touch with an ignoramus.

However, this did not prevent him from publishing an Albanian newspaper ‘Shqipetari’ which appeared for more than a year, and was from beginning to end nothing but an attack on the Greeks and the Slav states.

The Greek-Slav side, in a private meeting, decided to forward to the Russian Minister in Bucharest a declaration in which it was said, among other things, that the Albanians (that is, the Orthodox) would not work with Naço, who was an ignoramus and a vagabond; that they had the greatest respect for Russia, from whom they anticipated their salvation; and they begged the Minister to forward this expression of fidelity to his government, and to do with it and give it such publicity as seemed best to him. This declaration was signed by thirty or so Albanian notables.

III

About the same time, that is to say in 1887, Sami Bey Frashëri, brother of Abdul Bey and presently a member of the Council of State, obtained a firman permitting the creation of an Albanian school at Korça - a school whose upkeep was funded by ‘Drita’. At first the school roused great enthusiasm. Over 150 pupils attended, as many Christians as Muslims. But it soon wilted. On the one hand, a number of Albanians, at the instigation of the Turkish governor, began to make propaganda against the school, saying that the Muslims should not send their children to an infidel school; on the other hand, the Greek bishop excommunicated all parents who sent their children to the school.

For the same reason, a number of other national schools which opened a little later, at Pogradec, Starova and Luaras, closed after operating for only a few months. However, the Korça school kept going, thanks to the energy of Orkhan Bey. At the present time, about 80 pupils attend; but all from poor and for the most part Christian families.

IV

The Albanians of Korça also set up a society. As the government wanted to forbid this, Alo Bey was chosen as president, and by this means the government yielded. And it is odd that for one or two years an Albanian society should have existed and held meetings in Turkey.

V

In 1892 a girls’ school was founded in Korça by a Protestant Mission. This school has had great success. All the notables, the Muslims above all, send their daughters there. At the last examinations (August 1898), the governor, the kadi and many others took part. For the young Muslim girls, there was a separate examination in which many ladies of the same religion took part. The Bible Society has the intention of setting up similar schools elsewhere. The purpose of this Mission is certainly not just religious; I think it is without doubt directed against the supporters of Slavism.

VI

To return to the Albanians of Bucharest. They went on with their quarrels and their propaganda, without being seriously organised, for sure, but putting all their efforts into it. In 1890 an Albanian from Korça, called Kocof, arrived in Bucharest from St Petersburg. His aim was to organise the Slav party among the Albanians. He proposed to the Albanians: (i) to arrange for the Russian government to give an annual subvention for propaganda, (ii) to write the Albanian language in Russian script, (iii) words lacking in or lost from the Albanian language should all be taken from Russian, rather than be taken from Latin or created anew, and (iv) books should be printed on this basis.

In short, he proposed to turn the Albanian language into a semi-Slav dialect.

All this was received with enthusiasm, but it came to nothing. What one must never lose sight of, in discussing these Albanian parties, is that they had no organisation; that they were composed of ignorant merchants who had served in shops from the age of 15 to 25 or 30 before opening shops of their own and making their money; and that their idea of politics consisted in general of coming together and talking as though their wishes were reality. Further, it is very difficult to get the need for propaganda into such heads. They tell themselves that Russia and Greece have no need of propaganda, and that when the hour strikes, they will do what they want to do without hindrance. This state of mind is general among them.

Also, the representatives of the Russian government are very guarded with their maladroit partisans. And Kocof conceived such an impression of the Albanians of Bucharest that he did not follow up his project in any practical way. He was satisfied to distribute copies of an Albanian revolutionary march he had printed in Russia, and then left Bucharest.

VII

All the same, though these parties lacked true organisation they nonetheless kept in touch and propagandised. This is how they usually go about it: every week Albanians - merchants, muleteers, and others - return to Albania. The committee of the Greek-Slav partisans goes to see them: “So, you are off! Good journey! In your native village are such-and-such notables: go to see them, and tell them to speak against the project for an Albanian school which is being proposed. Tell them that it is a new instrument of oppression which the ‘Turkish’ Albanians have created against us. Moreover, Orthodoxy is in danger. You, you go into another village. Bon voyage! Tell a notable so-and-so there that you have heard he had put out a recommendation in favour of Albanian schools. But isn’t he in touch with what is going on? Doesn’t he know that all the Orthodox have backed out of such projects, because they have recognised that they are a snare? You others, when you see somebody, tell him not to go on being friendly with Muslims pretending to be patriots, because he will end up in prison. All the ‘Turkish’ Albanians are the same: they profess to be patriots to get you to talk, then they pass everything on to the Governor, and you are arrested.”

Hundreds of examples have acquainted me with this primitive and underhand propaganda of false patriots, whom the newspapers suppose to be so ardent on behalf of their nationality.

In 1888, Avramidhi Lakçe, an Albanian, millionaire many times over, sent to the people of Korça an extract from his will, in which he left for Albanian schools many hundreds of thousands of francs - nearly half a million. The executors were some Christians and a Muslim, Orkhan Bey. Doctor Manci, one of the executors, to whom the copy of the will had been sent, called together his Christian colleagues and spoke thus to them: “Avramidhi is leaving us 20,000 pounds if we would like to turn ourselves into Muslims. For he gives us Orkhan Bey as a colleague. Now I ask you: do you want to stay Christian and poor, or apostasise and make our town rich?” “We don’t want to become Muslims!” they all replied, and they returned the will to Avramidhi, telling him that it could not be accepted. This uncouth interpretation of a will in no way concerned with religion is characteristic. It proves the state of mind of the Albanian Orthodox, and it is hard to expect anything from them. They are not to be persuaded, and it would require planned and powerful efforts to knock anything into their heads, not least a concept of nationality.

Fourth Part (1895 to 1899)

I

In 1895, I found myself in Paris, where I learned for the first time about the existence of Albanian propaganda in Bucharest and the printing of Albanian books there. However, I had been concerned in developing my (Albanian) language since 1890, and I had formed a small library of all the books printed by foreign Albanian experts. I had even begun to write a few articles on Albanian nationhood for a Paris newspaper. That is proof that of Albanian propaganda there was none. For I was one of the few who, on his own initiative, concerned myself with this question; and on many occasions I had spent holidays of two or three months in Albania, talking everywhere about the national question, received coldly by some, and with incomprehension by others - and despite my interest in this question I was unaware, and everyone I knew was unaware, of the existence of an Albanian movement.

The fact is (I have since observed, and there are a thousand incidents to prove it) that for the Albanians of Bucharest, and even for those of Constantinople, the national question did not exist: there was only a municipal question. For them, in fact, the aim of all patriotic efforts was the national future of the town of Korça - and nothing else.

II

I wrote to ‘Drita’ to get hold of books, and when I had received them, I began to correspond with Naço. Thus we exchanged all our ideas about the future of the country. Some months afterwards, we decided to start an Albanian daily newspaper, and it was appropriate for me to go to Bucharest. But the money to cover the expenses we foresaw had not been accumulated - whether because the Romanian government thought the expenses too heavy for it to fund - for I believe Naço had made a request - or whether a major State highway Naço had undertaken and from which he hoped for big profits, had not lived up to his expectations - and we left the execution of our project for later.

However, while waiting, I decided to begin on my own publication of a periodical review which, to my way of thinking, should contain nothing but stories, poems and historical documents. In September 1896, therefore, I printed a prospectus-appeal which I circulated everywhere. It made a great impression, and I received hundreds of enthusiastic responses. However, I already had my reasons for thinking that the degenerate Albanian townsfolk were more enthusiastic in words than in deeds. I did not want to undertake this publication unless I could be ensured of making a go of it. And I expressed doubts about its success.

But I soon received a letter from Pandeli Evangheli, president of ‘Ditaria’, who assured me that he would take it on himself to collect 400 subscriptions in Bucharest and 300 in the rest of Romania. The people of Constantinople promised 200 subscriptions, and those of Monastir (Bitolj) a contribution of 20 Turkish pounds a month. I have all these letters. To trust in them, I would soon be able to publish the review every week, and with illustrations. And why should one not have trust, since they were all serious people, for the most part public officials, and hence moved by an irresistible patriotism which risked compromising them in such an enterprise?

Pandel Evangjeli

But we shall see that it was not a genuine enthusiasm. I may be forgiven if I stress somewhat the foundation of ‘Albania’, because I can show thereby the exact state of mind of the Albanians.

III

In 1895, I received a letter from a group of Albanians in Bucharest, saying they were glad to learn that I was concerning myself with the Albanian Question (I was once again in Paris); but that I ought not to compromise myself with Naço, ‘a vagabond and an ignoramus’; that I ought to be with them; and that they hoped to found a new society, ‘Dituria’. This society, when all is said and done, was no more than a venture by the Greek-Slav side. Pandeli Evangheli, the most able and most active man of the party, was chosen as president. This is the same man who, a little later on, as I have already said, took the responsibility for the 700 subscriptions in Romania.

IV

As soon as the first number of the Review appeared, the heads of the Greek-Slav side got together for discussions. They were extremely annoyed at the anti-Greek slant of the paper. They then convened a meeting where they proclaimed: 1) that this review was an initiative on the part of tyranny and oppression, because the editor was a Muslim; 2) that people must be prevented from thinking that the propaganda was due to the initiative of ‘Turkish’ Albanians; 3) that when the Greco-Turkish war broke out, such a paper could only prejudice Greek interests; 4) that there had moreover been attacks against Greek and Slav nationalities, and that nothing could justify such attacks.

Finally, some people thought the paper had received subventions from the Sultan to attack the Greeks. Others, that it was not an Albanian but a young Turk paper, because there were attacks on the Sultan in it. These self-same jealous partisans of the Sultan reproached me several months later for talking of the Sultan in an unfriendly way.

It was decided at the end of the meeting:

1) not to take out subscriptions to ‘Albania’;

2) to set up an Albanian paper in Bucharest in opposition to mine, and also to show that the Orthodox were doing something. As a result, of the 700 subscriptions promised from Romania I received only 34, these from the more clever members of the party, who did not wish to draw attention to their hostility. An account of this meeting appeared in the Greek paper ‘Patris’, published in Bucharest.

V

The Albanians of Constantinople are, as we saw at the beginning of this account, zealous patriots. They have made a good deal of propaganda in Albania; but this has been confined to a rather restricted group: the Tosk-Albanian functionaries. Beyond that, their propaganda has been non-existent.

The Albanians of Constantinople are not concerned with politics, to which they are indifferent. For them, everything cornes down to the question of the alphabet: in 1879 they adopted an alphabet created by Sami and Naim Beys (an alphabet of little practical use, as it cannot be printed because of certain special characters). Its authors put a relentless self-esteem to its presentation; for them everything is good which is printed in this alphabet, and everything bad which, being printed in another alphabet, seems to them to be challenging their glory as pioneers. So they greeted the appearance of ‘Albania’ with great enthusiasm, as I said that it would subsequently be printed in their alphabet, so long the necessary funds were available to cut the type characters. Naim Bey, president of the Turkish censorship and of the Albanian Committee of Constantinople, even set himself down as one of my colleagues, and his are the verses published under the initials N.F. (Naim Frashëri) and N.H.F.

But when they saw that the review went on being printed always in the same alphabet, for reasons I have made public, they changed their attitude, and while not going so far as to show hostility, they nonetheless had recourse to indifference.

In 1897, a clever student in Constantinople, Mehdi Bey, did a lot of propaganda for the review, and became a trustee. In this capacity, he went to Ismail Bey Vlora and other dignitaries of the Empire in Constantinople, and spoke to them on behalf of this nascent propaganda. He also distributed copies to people going by steamboat to Albania. But, nominated as attaché to the Governor of the Islands of the Archipelago, the Albanian Abeddin Pasha, he had to leave Constantinople. The son of Abdul Bey Frasheri, Midhat, was another propagandist. One day (June 1897), on leaving the Austrian post office carrying a large packet of ‘Albania’, he was arrested by secret police agents. Held prisoner for three days at the Ministry of Police, he was set at liberty thanks to vigorous protests by his uncle Sami, a member of the Council of State. Some days afterwards, he was nominated attaché at the Sublime Porte. From then on, he was only timidly involved in Albanian propaganda.

Mehdi Bey Frashëri

I mention these two facts only to demonstrate one of the weakest points about this propaganda: it depended on luck. Strong today in one place, it would be weak or non-existent the next, because one or two patriots had left. Whereas on the Slav side, people were exclusively occupied with propaganda.

Today (1899), Albanian propaganda in Constantinople is in the care of several students, of three or four Albanians from territories annexed to Montenegro in 1879, of several people from Scutari and of two or three officials in lower grades.

VI

Deceived by Bucharest, and let down by Constantinople, I turned to the people of Monastir.

They kept their word. They founded a kind of society, in order to raise funds and organise propaganda. The meetings took place in the house of Lieut. Colonel Halid Bey, an Army doctor. Copies of the review were sent to the British Consul, who passed them on to those interested. I sent them openly by post, and they reached him. The Consul, who is now in Ankara, knew Albanian and read the paper with interest. Unfortunately, because of certain quarrels he was having with the Turks, he ceased to undertake receipt of the review. So for some time the review did not reach Monastir. Again, some zealous patriots left Monastir - above all a teacher at the ‘Idahi’ school, Shevket, who was nominated head of a similar school at Üsküb. However, soon afterwards, the Bible Society of Monastir took upon itself to take several issues to pass on to their recipients.

VII

Such were the beginnings of this work. What were the subsequent developments, and what is the present state of Albanian propaganda? The paper started at Bucharest against ‘Albania’, under the name of ‘Shqiperia’ was at first frankly hostile to me. But when the director was changed (following the circumstances outlined by me in ‘Albania’ no. 9 (A 159) the paper came into the hands of V. Dodani, an honest man and a patriot, who is not the tool of the Slav party, or the Greek and Italian, although equally he is not aware of the snares. In fact, he publishes the articles with which he is provided, and of which he does not understand the ‘slant’. He could do with a little more in the matter of intelligence.

VIII

However, he willingly lent his presence to a secret meeting at which about ten notables and the Serbian Consul at Bucharest took part. This took place in the month of May 1898. The Serbian Consul suggested an initial funding of 40,000 francs to start propaganda in favour of a rising in Albania to create an autonomous government linked with Serbia. But one of the people taking part, Gavril Pema, an intransigent pro-Greek, said that if there was only a question of money, it was more logical to ask for it from Greece; and next day he made public the secret of the meeting.

IX

Alongside the paper ‘Shqiperia’, another paper, ‘Ylli i Shkjiperise’ (Star of Albania) had lately appeared in Bucharest. I rather encouraged the publication of this paper, and thought it would follow a good line. The man who principally took on the publication struck me as patriotic and intelligent. Unfortunately, others got mixed up in the paper, notably one George Meksi (of whom I have spoken in ‘Albania’ (A159), and the paper suddenly made a violent Slavophile turn. According to a letter I recently received from Bucharest, the editors of this paper are in touch with the Russian Legation.

X

The attacks that Ylli launched against ‘Shqiperia’ led one to hope that these two papers might to a point neutralise each other. Further, ‘Shqiperia’, which was on quite good terms with us, came still closer as a result of these attacks. That at least was what I was led to think from a letter from the editor, V. Dodani.

XI

Nonetheless, the propaganda of the Greek-Slav side against Austria did not die down so soon. And, on this subject, it is interesting to note how this propaganda is conducted.

The Albanians of Bucharest, aware of the weak point of their Orthodox compatriots, have adopted the tactic of spreading the rumour that the Austrian aim is to convert them all to Catholicism. This ridiculous allegation is their only weapon, but it is a strong one, and quite enough for such uneducated minds. On the other hand, they say to Albanian Muslims:

“As for us, we are Christians; it is therefore in our interest to go along with Austria, as a Christian power. But you, being Muslims, would pass into a state of slavery under this Christian power. That is why we lay aside our own special interest, regarding rather the general interest, and we say to you: take care, let us take care!”

Such is this perfidious and incessant, if irregular, propaganda. It must be said that it has little effect among Muslims, those in the movement being generally very sympathetic towards Austria. But its influence is very great among the Orthodox.

XII

In this regard, I made a number of strange observations during my last visit to Bucharest. We were given a splendid and enthusiastic reception, as if we were our country’s saviours. This display would have been even greater, if I had not cooled it and caused some irritation by sending from the Vienna railway station a telegram announcing our arrival, not to the Greek-Slav committee, but to the Drita of Naço.

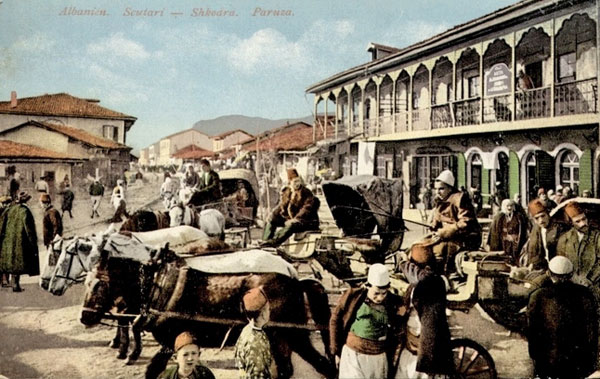

Carriages in Shkodra.

Early coloured postcard.

Arriving in Bucharest and seeing this enthusiasm, I said to myself: ‘This is odd, and I find it surprising, coming from these ordinary and unconcerned tradesmen...’ Nor was I wrong. Some days afterwards, it was suggested to me that I should carry on with ‘Albania’ in Bucharest; that ‘Shqiperia’ should cease publication, so that I could have all its readers; and that a management committee should ensure 10,000 francs a year for the papers.

In the many meetings we held, Murad Toptani explained an overall propaganda project. A number of specific reservations were made about insurgent bands. They were supported, but on condition that they attacked only Turkish officials, and not touching Bulgars and Greeks, as Murad proposed. With this reservation, the project was accepted, and it was resolved to continue with a funding of 150 to 250 thousand francs. But when Murad Bey raised the question of the headquarters of this propaganda effort, and told them that Dalmatia or Bosnia seemed most suitable to him, there was at once a glacial silence.

Finally, P. Evangheli said that they saw no objection to this, but there was a risk that funds would not be forthcoming under such conditions, “because the other Bucharest Albanians are fanatics, and would not agree that the centre of the propaganda should be in a Catholic state.”I took up a waiting attitude, as I realised that it was all quite useless, and the money would never be forthcoming. Nor was I mistaken. For four months they kept Murad Toptani there with promises that were never honoured. The only thing I obtained was the signature, in public session, of a telegram to the Sultan, whose text I had prepared.

XIII

With such a state of mind, an understanding could clearly be made easily between the Albanians of Bucharest and those who call themselves such in Italy. An understanding all the stronger in that the Italo-Albanians are Catholics, but of the Greek rite, and allow the marriage of priests (matters which bring them quite close to the Orthodox) - an understanding even stronger because they probably favour Montenegro in Albania, given the powerlessness of Italy. My view on this point is entirely shared by Murad Toptani.

The Italians do propaganda in southern Albania through the Albanians of Bucharest, and in northern Albania through the Italian Consulates. To their Albanian college and seminary at San Demetrio Corone and in Sicily - where, by the way, not a single word of Albanian is taught - they attract a certain number of young people, and so sustain in Albania a current of opinion in favour of the Albano-Italian colony. We may note in passing that: 1) appearances notwithstanding, there is complete agreement among Albano-Italians, as is proved by the fact that their alphabets are identical as to letters; 2) that they do not know how to speak Albanian. (Murad Bey confirmed this for me, as others had done.)

XIV

To widen the scope of their agreement, the Italians and the Albanians of Bucharest sought the support of those in Egypt. The Albanians of Egypt, who are quite numerous, are the richest merchants of Albania. They are in constant touch with their native land, and take an interest in the national movement. They have founded a Society, ‘Albanian Brotherhood’, and recently proposed to publish an Albanian newspaper.

One of them, Efthim Mitko published in 1878 ‘The Albanian Bee’, a collection of popular tales and stories: this is the best book so far published in the Albanian language.

But, set in a milieu far away from Orthodoxy, in daily contact with Westerners, their outlook is far from being as restricted as that of the other Albanian Orthodox. Moreover, despite the efforts of a certain Adhamidhi, a Cairo doctor, representative of the Greco-Slav party in Egypt, no understanding has been reached between them and the Albanians of Bucharest. The situation of ‘Albania’ in Egypt is, on the contrary, quite good.

XV

The Albanians of Bucharest have done better with those of Sofia. It is true that they, being mostly workers, cannot give much time to propaganda.

Moreover, there are two other parties in Sofia. Thus:

i) Albanian. This society is pro-Slav, and its seal is surmounted by a cross, thereby repudiating any purely national union, and making of the Albanian question merely a religious question. It has relations with ‘Dituria’ of Bucharest.

ii) The ‘Bashkimi’ (Unity) society, run by Kristo P Stefan, who prints every year an almanac in the letters used in Constantinople. This almanac is edited by Midhat, son of Abdul Bey Frasheri - The ‘Unity’ society is patriotic, and has the support of the Albanians of Constantinople. (Kristo P. Stefan is at the same time one of our Sofia correspondents.)

iii) The Turkish paper Ittifak, edited by Yusuf Ali Bey. Yusuf Ali is from Kertchova, where Albanian and Bulgarian are spoken. So he speaks both languages, and has been able to win the confidence of both the Sultan and the Bulgars. Apart from a subsidy which it gives him, the Bulgarian government exerts, through the police, a pressure on Muslim Bulgars to subscribe to Ittifak, saying that it is their duty to educate themselves and abandon their gross ignorance. This extraordinary fact I learned both from letters from Bulgaria and by word of mouth from a friend of Y. Ali living in Bucharest. It should be noted that, every time he goes to Bucharest, Y. Ali is the guest of Duro. ‘Ittifak’ is quite widely circulated in northeast Albania.

XVI

The story of the various propaganda efforts has afforded the opportunity of speaking, on several occasions, of the state of mind of the Albanians. Now let us say a few words about the situation in Albania itself.

In general, Albanian officials in Albania are animated with the best feelings. Many can read and write Albanian. In the districts of Korça, Kolonia, Berat, nearly all the Beys keep up their language. In Elbasan, Monastir, and elsewhere there are a great number of them. It should be noted above all that young people in the schools are very interested in the national question. The country people, and above all the ‘zapties’, in the vilayet of Monastir notably, almost all can read.

In Northern Albania, the national movement is much less bright. I am talking above all of the Muslims. Nearly everyone there is even unaware that people have begun to write their language. However, among the Muslims of Dibra, Mat, Tirana, and the coastal towns, a national movement is beginning vaguely to take shape.

But, almost everywhere, Albanian schools would be well received. Among the towns where they are actively hoped for, one may mention Elbasan, Kolonia, Valona, Permet, Tepelen, Vertsche, Dibra, Ohrid, Tirana, Mati, and many small towns. Elsewhere, they would be received with an indifference which would quickly change into sympathy.

XVII

To conclude, there is in every Albanian head the germ of an idea, but this idea is neither old enough nor strong enough to get them into action. Why? Because at no time has there been a concern to develop these thoughts. The initiatives so far taken prove that educated Albanians have goodwill; but what are such initiatives by comparison with the tenacious, strong and well-organised efforts of the Slavs and the Greeks?

The number of those who read and understand, and have some influence, is small enough in Albania, and I can say that all of these have more or less read ‘Albania’; but beyond a certain point it is hard to find readers, because there are no more left who can read a newspaper fluently. By publishing articles in Turkish, one increases the number of readers, particularly in Northern Albania. The Albanian people are sufficiently awakened to show understanding, but one must bear in mind that nothing has been done to make them understand anything at all.

Caught between the Albanians of the North, who do not know how to read, and those of the South, who are suspicious, and see snares everywhere, the propagandist can only go forward through a thousand difficulties.

Collaborators, above all, are lacking. And the reason collaborators are lacking is the absence of schools. Where a school exists, there in effect is a nucleus for propaganda; and collaborators arise and take it on themselves to distribute publications. At Korça, quite some time ago, ‘Albania’ was read in the cafes because from the moment an Albanian school existed, the Turkish government could not stop people reading Albanian.

One of the greatest difficulties in setting up schools is to find capable teachers. The Korça school was for a long time discredited, because for some time a tailor was put in as teacher, who knew just how to read and write.

What is needed is to set up a college, whether at Zara or Sarajevo, or in Albania itself (at Orosh, for example) with the double aim of quickly giving a substantial training to future teachers of Albanian, and of attracting young people of more or less influential families in order to give them - as is done by the Albanian college in Italy - a complete education.

That is a simple idea, after all. But what I wish to say above all is that day by day Austria engages greater sympathy among educated Albanians; and that if a means could be found of giving greater cohesion to these sympathies, a very strong movement would be created.

Fifth Part

An alphabetical list of all Albanians who, directly or indirectly, in favour or against, were involved in the patriotic movement, with a few words on each of them.

ABEDDIN PASHA: Former Minister of Foreign Affairs; at present Governor General of the Archipelago. A good patriot, but cautious.

ALO BEY (KORÇA): Dealt in leeks as a young man; later turned himself into an intermediary between Turkish officials and anyone who had a case to settle. He is actually a protector of brigands, whom he furnishes with victuals and shelter in winter. They share the profits, and in this way he has become rich and quite powerful. He is a patriot in the sense that he does not want to see the government infringe local liberties; has often been linked with the pro-Slav faction, and the Russian consul in Monastir stayed with him on his last trip to Korça: but all that is to give him importance in the eyes of the Turkish government.

AHMET BABA OF K: Bektashi monk and excellent patriot. He was deported to Tripolitania, whence he escaped with Murad. (A curious detail: he dresses like us, and wears a hat since going to Italy - and now in Corfu: which shows how the Bektashis, even when monks, differ from Muslims.)

AKIF Bey: nephew of Dervish Bey, a moderate patriot.

DERVISH Bey: An ardent patriot, but not very bright, and awkward. (His sister married a Vrioni, and she is a great propagandist for Albanian, which she writes and cultivates, among the women of Berat.)

DUÇI Nicolas: originally from Korça, a prominent merchant, the most important and most patriotic of the Albanians of Egypt. He is president of the ‘Albanian Brotherhood’. (His son, Michael Duçi, has written verses for ‘Albania’, which he encourages in Egypt.)

DODANI Visarion (Bucharest): honest man, patriotic, rich, vain, of moderate intelligence; he took the newspaper ‘Shqiperia’ in hand, half for patriotic reasons, and half so that he could become involved with the journalist-deputies of Romania.

DEMIR Bey PEKINI: Unconcerned with everything. The Tanzimat (Constitution), which suppressed seignorial privileges, seems not to have affected him. He levies taxes when he is in need of money. (Married an aunt of Murad Bey.)

DAUT: Bektashi Sheh of Tepelen: Has patriotic sentiments.

DATZ Shapir aga: patriot of Dibra; fought vigorously against Demir Pasha when he was sent by the Sultan to disarm the country.

DURO Hercule: a threefold millionaire; none the less he still runs four or five grocery shops. He was born in the village of Boboshtica (Korça) and lives in Bucharest. (His father, Zhemeli Duro, who died two years ago, was an ardent patriot.)

EVANGHELI Pandeli: originally from Kolonja; very intelligent, pliant and able. His voice preponderates among the Albanians of Bucharest. Is strongly pro-Greek, but would favour Russia quite as much, since his whole aim is Orthodoxy.

VISARION: Orthodox Bishop of Elbasan: Was an ardent Albanian until the Russian agents arrived at Shpat and Elbasan (February/March 1897).

GHECIO: one of the Bucharest millionaires. All the same, his avarice prompts him to oppose any enterprise of a national character, so that he won’t have to make a contribution towards it. Otherwise, he is an intolerant Orthodox.

GOSTIVARI Bey: compared with other chiefs from his part of the country, he is a patriot. His son Kiamil is one even more. They have great influence in the area. Kiamil recently married the daughter of an Üsküt chief. (Kiamil assumes, voluntarily, the rôle of head of the Gostivar telegraph bureau; when, which happens rarely, a telegram is to be sent off, he operates the machine in the presence of several friends, and he passes for an expert.)

HAMDI Bey: the best of the Albanian patriots. So much so that if he should come out of prison, after so many years of preventive detention, he will certainly start propagandising again. Grandson of Ilias Pasha. His family have great influence in Dibra. He was arrested as a resuit of a denunciation by the Orthodox ‘patriots’ of Bucharest.

HALID Bey: Lieutenant-Colonel, Army doctor at Monastir. Excellent patriot, who spread his ideas among the people around him.

HUSREF Bey (at Starova): Same origin and same type as Alo Bey, but less dishonest. Supports the Albanian school which has been operating for two years in Starova.

HARITON Thanas: One of the Bucharest notables. Honest, stubborn, and a little simple. Goes into raptures about ‘true and well-lit paths’ and is always repeating that Albania must ‘get there’, never mind how. (Originally from Korça.)IBRAHIM Edhem: Originally from Kolonja; secretary of the Bank of Salonika in Constantinople, where he is tireless in making propaganda.

ILO Dhimitri: lawyer, edits the paper ‘Ylli i Shkjiperise’. Has neither patriotism nor any conviction at all. He is despised by everybody, not only because of his infirmity (for his nose was completely chopped off by a stone which once fell on his face) but also for his untrustworthiness. He received for his paper, monthly: 1) A hundred francs from the management of the Greek paper ‘Patris’ of Bucharest; 2) a subvention (probably) from the Russian government; 3) a sum (certain) from Albanians involved in business in Odessa.

IONUS Aga: Patriot of Üsküb. Has influence. Cannot read.

ISMAÏL Pasha, of Elbasan. One of the three or four richest Muslim Albanians. Is rather on the side of the government, though he does not oppose the national movement.

ISSOUF ALI Bey: Editer of the ‘Ittifak’ at Sofia; cares for nothing but money. At present money cornes to him from the Sultan and from Bulgaria.

KERITZA Mihail: Albanian-Vlach, one of the Albanian notables of Bucharest; an unremitting supporter of Greece.

KOLEA Sotir: of the Commercial Company of Salonika Ltd. A good patriot, and well-informed. For five years he has been preparing a great Albanian dictionary. Sometimes writes for ‘Albania’.

KYRIAZI: Albanian from Korça, Bible missionary at Monastir. Ardent patriot. Recently published a bulky Albanian manual of arithmetic under the pseudonym Athanas Sino.

KARDHO Mandi: Nephew of Duro; merchant, like all the Albanians of Bucharest. Ardent patriot.

KUNESHKA Vani: Friend and colleague of Kardho. Patriot. (These two Albanians are among the strongest supporters of Austria at Bucharest.)

KARBUNARA Dude (Berat): Friend of Islam Bey Vrioni. Wanted to set up an Albanian school some years ago. Passes for a patriot.

KOSTURI (I forget his forename; I think he is Vasil Kosturi.) Merchant of Korça, where he lives. He is the leader of those Korça people who sincerely want Albanian unity without distinction of religion. An honest man, somewhat reserved.

LUARASI Dzafer: Lives at Korça, relation of Naim Bey. A true patriot, but somewhat timid.

MOLE Dhimitri: Originally from Korça. Merchant at Philippopolis. One of the rare Orthodox who is neither pro-Greek nor pro-Slav. Makes good propaganda, when he spends a month or two in Albania.

MIDHAT: Son of Abdul Bey. Secretary or attaché at the Sublime Porte. Active and intelligent young patriot. Has written several articles for ‘Albania’. Has translated the life of William Tell into Albanian. Favours Austrian influence very much.

MEHDI Bey FRASHERI: Attaché to the Governor-General of the Archipelago; very keen young patriot; showed remarkable activity when he was in Constantinople, where propaganda is to be made among 50,000 Albanians.

MAHMUD Pasha of Elbasan: Patriot, but cautious. One of his three daughters married General Saadeddin Pasha (a Turk). His son-in-law is son of the (word illegible) Ali-Sait Pasha; and when this Minister of War was alive, Mahmud had considerable power.

MEHMED-ALI Pasha of Delvino: Governor of Korça; belongs to the oldest family of Delvino; great grandson of Selim Pasha of Delvino. A decent man, with affable manners, and patriot in a relative fashion. He said, on arriving in Korça: “I don’t want any religions divisions and quarrels. You are all Albanians.”

NAIM Bey: Brother of Abdul Bey. President of the Censorship Commission; ardent patriot, author of most of the books published in Bucharest. Has been ill for five years. Always speaks of Austria in the warmest terms.

NAUM KRISTAKI: Albanian from Korça, landowner in Romania. Would be well inclined to spend several thousand francs a year on propaganda, if the Greco-Slav party did not worry him with endless intrigues.

NAÇO Nicolas: Ardent patriot, speaker, and able propagandist. His defect is being a bit of a bragger, and vain. Contractor for State roads. Receives a subvention for his school from the Romanian government. Is a supporter of Austria.

NASUH Effendi, at Kolonja: former examining magistrate at Monastir. Keen and influential patriot. Comparatively rich for the region.

ORKHAN Bey, son of Cecis Bey: One of the best of the Korça patriots. Has been a keen supporter of the Albanian school.

PEMA Gavril: Head of the pro-Greek party in Bucharest. Has a certain disdain for his political friends, since they are merchants and he is a manufacturer. Comes from Korça.

REDZEP Pasha, Marshal: Seven years ago he asked for an audience with the Sultan, and asked him to do something for Albania. The Sultan promised him a reply next day, and two days later Redzep Pasha was exiled to Baghdad, under cover of his appointment as Commander of the 6th Army Corps.

RIZA Bey, son of Halil Pasha of Monastir. Counsellor of State. A patriot, but not so far as to risk his position.

SAMI Bey: Counsellor of State; brother of Naim, but less of a patriot than him. Has published an Albanian grammar.

SHEFKET Bey: Head of the Turkish College of Üsküb. Ardent and genuine patriot, but timid. Has published an article in ‘Albania’ (A 4l).

SPIRO Dina: Merchant at Shibin-El-Kom (Egypt). Passes for a patriot, although he took for himself, along with Vreto, 800 Turkish pounds (17,000 francs), which the will of an Egyptian Albanian had bequeathed for Albanian schools.

SHAHIN Bey: Native of Kolonja. (Recently nominated as deputy governor of a district in the vilayet of Monastir. I haven’t received any news of him since he left Constantinople.)

SHIROKKA Filipp: Engineer-draughtsman, native of Scutari. Presently in Cairo. Ardent and well-informed patriot. He is our best Albanian writer. Assiduous collaborator with ‘Albania’, under the pseudonym of Geg Postripipa.

SARAC Ismail Bey: One of the best-known patriots of Dibra.

SALIH Bey: At Durazzo; (I think he is from Schiak). He formerly asked Dr. Themo that we should print an alphabet. He proposed to arrange for the opening of a school.

SELIM Bey, of Delvino: First cousin of Mehmed Ali Pasha (see above). Has no patriotism, but knows the way the wind blows. Very influential, and also one of the most intelligent and nice Albanians. He is called ‘the diplomat of Laberia.’

SPIRO KIOSE SOLHAK: The delegate from Shpat to Constantinople, in 1896, to present a petition to the Embassies of Austria and Russia. (This petition was drafted by Murad Bey.) Spiro Kiose is a patriot and moreover an able man. He is the person most capable of doing propaganda in Central and Southern Albania.

TOPTANI, Murad Bey: Ardent patriot, quite intelligent, but without following things through. He is, with the Marquis of Aletta, one of our two candidates to an imaginary throne. Son-in-law of Naim Bey. Abhors the Slavs, and is very sympathetic to Austrian influence.

TOPTANI, Refik Bey: His brother; as good a patriot as Murad, he is better informed.

THOMA, Abrami: Ardent patriot, and a passable writer. Taught for some time at the Albanian school in Korça.

TARPO Brothers: Three brothers in Bucharest, under Dodani. Less given to intrigues than anyone else. Their house at Korça is used to house the Albanian school. One of the three, Petri, who has no children, will leave (so it is said) several hundreds of thousands of francs to Albanian schools.

Gergio Christian, son of the eldest of the foregoing, is a student in Berlin, and a good patriot from whom much is to be hoped.

Dr. THEMO: Excellent patriot, formerly Army major, left Constantinople in secret because he was suspected of being a Young Turk. Actively involved in Albanian propaganda. At present a doctor (municipal doctor) in the town of Medschidie.

TZIKO: Suli family, emigrated to Padua about the beginning of the century. Have nothing to do with the Calabrians and Neapolitans. But all the same, good patriots.

VLORA Fend Bey: Known for his vengeance by means of false denunciations. On several occasions he set himself against the national movement. Presently Vali of Konya.

VLORA Sureya Bey: Kinsman of the above; had intelligence contacts with Italy and was arrested and sent to Constantinople - the exact date I don’t know.

VLORA Ismail Bey: Kinsman of the previous couple; member of the Council of State, a man of great worth and of dignity, and not lacking in patriotism. Married a Bulgarian (wrongly thought to be a Greek).

VLORA Dzemil Bey: Son of Selim Pasha and kinsman of the preceding three. One of the young patriots with most zeal and intelligence. (He proposes to come to Brussels for a few days.)

VRIONI: In general, all members of this family are patriots; but above all Islam Bey, Salih Bey - who is preparing a small dictionary - and his son Nuzhet, (The late Mehmed Ali Vrioni Pasha was a much-appreciated satirical poet. He used to improvise very cutting epigrams in Albanian. He was very active with Abdul Bey in 1880.)

VROTO: Originally sent by the Albanians of Constantinople to found ‘Drita’ in Bucharest. Has written two or three pretty bad books. Receives a small pension from the Greek-Slav side to make propaganda against the Albanian language, and to say that only the Greek and Slav languages are worth anything. Aged between 80 and 84.

ZOGOLLI Dzemal Pasha: Vice-governor of Mati, where he has powder mills. Good patriot, but does not understand the need for schools.

ZOGOLLI, Dzelal Bey: Brother of the foregoing. Equally patriotic. These Albanians have great influence.

[Mémoire sur le Mouvement National Albanais, Brussels, January 1899, translated from the French by Harry Hodgkinson. Centre for Albanian Studies, Harry Hodgkinson Archive. The original version is preserved in: Haus- Hof und Staatsarchiv, Vienna, Karton 18 der Gruppe XIV (Albanien), Folio 358r-401r. Obtained from the Vienna Archives by Dr. Ihsan Toptani. Published in: Faik Konitza, Selected Correspondence 1896-1942, edited by Bejtullah Destani, introduction by Robert Elsie. ISBN 1-873928-18-1 (London: The Centre for Albanian Studies, 2000), p. 144-173.]

TOP