| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1904

Karl Steinmetz:

Expedition into the Northern Albanian Mountains

The family of Mirash Vuksanaj in Shala, ca. 1930.The Austro-Hungarian explorer and travel writer, Karl Steinmetz, was an engineer by profession. After an extensive trip to South America, he journeyed several times through the Ottoman Empire before venturing into its wildest part, the mountains of northern Albania. In August 1903, he set off on an expedition through the mountains from Shkodra to Gjakova and Prizren in the summer heat. Soon after his arrival in Skopje, he sailed right back to Albania by steamer from Salonika to San Giovanni di Medua (Shëngjin) where he arrived on 12 September, to begin a second expedition which took him through Mirdita for two weeks and back down the Drin Valley to Shkodra. In August 1904, he returned to Albania to explore the northern mountains once again. This journey took him though similar territory, but slightly to the north, through the high mountains of Shkreli, Theth, Shala and Merturi on to Gjakova. A third expedition in 1905 took him once again through the northern mountains, this time in the direction of Mat and the valley of the Black Drin in Dibra country. Steinmetz’s travels are described in his three German-language books: "Eine Reise durch die Hochländergaue Nordalbaniens" (A Trip through the Highlands of Northern Albania), Vienna 1904; "Ein Vorstoß in die nordalbanischen Alpen" (A Venture into the Northern Albanian Alps), Vienna 1905; and "Von der Adria zum Schwarzen Drin" (From the Adriatic to the Black Drin), Sarajevo 1908. Together with Baron Nopcsa and Edith Durham, he was regarded as one of the best informed foreign travellers of northern Albania in his day. Karl Steinmetz learned Albanian and was also the author of an Albanian grammar and dictionary: "Albanische Grammatik: nordalbanische Mundart" (Albanian Grammar: Northern Albanian Dialect), Sarajevo 1913; and "Deutsch-albanesisches Feldwörterbuch" (German-Albanian Field Dictionary), Sarajevo 1913.

It was in the heat of August 1904 that Karl Steinmetz set off from Shkodra. His goal was the forbidden Muslim town of Gusinje (Gucia), now in southeastern Montenegro. Having arrived in Theth (Nrejaj), however, a dispute between the native tribesmen forced him to change his plans.

Two Dukagjini men smoking (Photo: Shan Pici, 1938).

Shkodra is not an attractive town to spend much time in. For this reason, as soon as I arrived, I applied to the Austro-Hungarian Consulate General for the permit I needed to travel in Turkey, the yol-teskere. On the following day, I was informed that the governor was not allowing travel in Albania pursuant to a directive that had reached him from Constantinople a few weeks earlier. They thus refused to issue the travel permit despite the fact that Consul Rémi von Kwiatkovsky did his best to support me, and I am very grateful to him for this. I therefore had no choice but to set off without permission. The teskere is not needed in the mountains at all, and once I got across them, into the Vilayet of Kosovo, I would just have to see how to deal with the authorities.

I left Shkodra at the break of dawn on August 9th in the company of two men from the town, taking back roads to avoid the Turkish guard posts checking the main roads. Since we had good horses, we were able to ride in a trot almost all the way across the plain – interspersed with meadows, fields and groves of trees, that stretches between the mountains and Lake Shkodra. The countryside only changed when we reached the trail leading to Kastrati and Hoti, near Hani i Çesmës, and turned right. On our right side were barren stony hills and on the left, a flat, slightly sloping plain covered in rocks as big as fists or heads. We crossed the dry bed of the Benushi River, carved deep into the landscape, which in the rainy season discharges its water into the lake, and stopped for a short while at Hani Koder Ars, where there is a little shop among the tall trees. The shop offered coffee and was always abuzz with activity because it had the only well within an hour’s walk. Around noon, we reached the Proni i thatë creek at the point where it emerges from the gorge. We crossed its bed, stony and completely dried out, and climbed up towards the church of the Shkreli tribe at the settlement of Bërzheta, about 40 m. in elevation above the valley. It is a simple building but somewhat larger than most of the churches one encounters in Albania. Beside it was a large, two-storey vicarage belonging to the missionary, a diocesan priest. On the steep slopes around it were a number of farmhouses, trees and small fields carved out of the rocky soil.

The missionary was not there and had been gone for several weeks. I did, however, manage to meet his representative, a young priest, as well as the missionary of Boga, Dom Noci, who was there for a short visit. Dom Noci intended to return home that afternoon, so I decided to join him. I dismissed my guides and we set off for Boga late in the afternoon.

The trail took us up the narrow valley of the Proni i thatë creek. Initially the slopes were covered in bushes but higher up, there were imposing cliffs with steep embankments, some of which were covered in shrubs. Our surroundings were bleak and desolate indeed. Neither grass nor water. Proni i thatë (Dry Creek) was the perfect name for the valley. It is the stoniest and most arid region in all of the Highlands and, for this reason, the Shkreli tribe that lives here does not do any farming but only herding. In the summer, they drive their animals up into the lush mountain pastures, and in the wintertime they keep them in the lowlands and feed them on hay they bring down from the mountains and on cobs of corn. Only a few families move south to the warmer coastal region in the winter. In this sense, the Shkreli are different from their northern neighbours, the Kelmendi, almost all of whom spend the winter on the coast south of Shkodra.

The Shkreli are a comparatively wealthy tribe consisting of about 600 families, of whom most (about 500) are Catholic. The rest are Muslim. The largest settlement in Shkreli is Vrizi at the foot of Mount Veleçik where the bajraktar, Vat Marshi, lives. The other settlements are – according to size – Bërzheta, Dusej, Dedaj, Stërkuja, Pojica, Grizhaj, Stillo and Zagora.

After crossing the meagre flow of a spring, about two hours northeast of Bërzheta, we came to a small, flat plain with some corn fields and a few houses here and there. This was the settlement of Dusej where the northeastern direction of the valley makes a turn northwards. At this spot, the trail enters a ravine, only about 2 m. wide, and proceeds for some time up the narrow gorge that also serves as the bed of the creek. Thereafter it opens up into a pleasant valley with gentle slopes covered in meadows, fields and houses here and there. On this side of the gorge, the region is called Gryka e Dusejt (The Gorge of Dusej).

On the other side of the creek, one comes upon a gushing spring of ice-cold water with a trough for animals to drink in a grove of lofty beech trees. It was a perfect spot for a rest. We had a kahvexhi (coffee man), who had taken up residence here in a primitive hut, make us a steaming cup of coffee. Night was approaching so we were soon back on the trail up the left side of the valley, stumbling over stones. At the point where the valley turns eastward, one leaves Shkreli territory and enters the region of the Boga tribe. We reached Preçaj in the dark a quarter of an hour later, where this tribe’s church is located. In accordance with northern Albanian tradition, the church is named after the tribal territory it is in, and is thus simply called the church of Boga.

The Boga actually belong to the Kelmendi tribe and constitute one of its four bajraks. In actual fact, they have very little contact with the Kelmendi because the latter live in the valley of the Cem, from which the Boga are separated by a 2000 m. high mountain range. The Boga are made up of about 75 families that, with one exception, are all Catholic and live in the following nine villages: Gjokaj, Preçaj, Malej, Gegaj, Mihaj, Leshaj, Mikaj, Ulgjekaj and Nrej. The bajraktar, Llesh Sokoli, does not live on tribal territory but on the plain of Shkodra and only visits Boga for a couple of weeks each year. The rest of the time he is represented by Zejf Prenka. The Boga, too, are primarily herdsmen because there is very little farmland, only around Preçaj.

House interior in Dukagjini

(Photo: Dedë Jakova 1937).

As we arrived late in Preçaj, I was only able to have a good look at the surroundings the next morning (August 10th). Here, too, the fields rise gradually up the slopes until they change into steep rocky cliffs. Most of the houses are on the right side of the valley, whereas the church is on the left.

Although one has the impression on the trail from Bërzheta to Preçaj that there is no particular difference in elevation, Preçaj is actually rather high. The measurement for Bërzheta was 580, whereas for Preçaj it was 920.

At my request, the missionary there got me a young man to take me to Theth. In contrast to my experience the year before in Dushmani, Toplana and Nikaj, where my guides never even mentioned the issue of remuneration, this fellow wanted to know how much he would get, and indeed demanded quite a hefty sum. The same thing occurred in Theth (and later in Raja), but this is due to the fact that Theth and Raja are situated on the most frequented trails leading from Gusinje and Peja to Shkodra. Accordingly, the population here has had more contact with the outside world. Albanians are endowed with great natural intelligence and learn quickly how to take advantage of situations. In dealing with foreigners, they are convinced that everyone from abroad is immeasurably rich because they have come all the way to visit the mountains just for fun. Half a medjid (two crowns) per person and day is usually considered a good wage.

Having reached an agreement with my guide in Preçaj, we set off on foot because the path from here on is unsuitable for horses. Just past the church, one crosses a gushing spring of water near which there are two shops (dugoj) run by men from Shkodra. They are both exceptionally primitive and have only very basic provisions such as salt, coffee, scarves, needles and thread, etc. Beyond Preçaj, the valley narrows to a gorge with cliffs. The farmland ends here and one proceeds up a wild ravine in which one is forced to clamber over rocks and boulders. Shrubs and tall beech trees grow in the ravine, too, above which are massive cliffs. It is one of the most romantic landscapes in all of the Highlands. The path, if one can call it such, continues up to the end of the valley and rises up into a splendid forest of tall beeches in stony soil. We climbed higher and higher. The beech trees were now replaced by conifers until the forest came to an end in a small barren basin just below the pass. The basin, called Gropa e Borës, is surrounded by cliffs covered in deep snowdrifts. In the middle of the basin, we came across a poor soul in a primitive stone hut who was busy brewing coffee there for passers-by. There is no water to be had at this elevation so, to make the coffee, the fellow used snow which he melted in a wooden vessel.

The trail divides near the hut. To the left was a difficult path up over the Maja e Vijavet directly towards the valley of Gusinje. To the right was another trail, suitable for packhorses. It ascended the slope over scree and a large patch of snow to the pass. I chose this trail and in twenty minutes I was on the Qafa e Shtegut të Dhenvjet, meaning Sheep Trail Pass, the highest pass in the northern Albanian Alps. The aneroid showed that we were at 1770 m. in elevation. The pass is only a few metres wide. To its right looms a lofty cliff.

When I got to the other side of the pass, I had the impression that curtains had suddenly been drawn open before me. An extraordinary view presented itself. At my feet was a rock face that descended almost vertically. Far below me, at the bottom of the valley, I could see verdant fields and meadows, the Valley of Theth, through which a river meandered. To my right and left were snow-covered mountains, jagged ridges and awesome cliffs rising into the blue sky. Only in the southern part of the valley are there slopes covered in brush and woodlands. To the north, there were only barren cliffs in hues of white and grey. The scene was majestic but somehow intimidating as well, because the many of the precipices before me plunged 500 m. right into an abyss. Not a blade of grass grew there. [...]

Dukagjini woman carrying a basket

(Photo: Pjetër Marubi, 1870).

Having enjoyed the panoramic view from the top of the Sheep Trail Pass, I began to make my descent. The path was steep and extremely arduous. [...] After clambering down over the rocks and scree for several hundred metres, I eventually reached a part of the mountainside that was covered in grass, bushes and trees. Here there was a juncture in the trail - one path to the left followed down into the valley for another half an hour and then up again to the Peja Pass. This is the trail to Gusinje. The path to the right continued steeply down the mountainside through the bushes until one reached the first fields and pastures. I passed several farmhouses until I got to two watermills beside the swiftly flowing crystal-clear waters of the Shala River. Even when it is hot out, the river is freezing cold all the way down to the end of the valley where it flows into the Drin. This is because it is fed directly by the snow up in the surrounding mountains. It makes excellent drinking water.

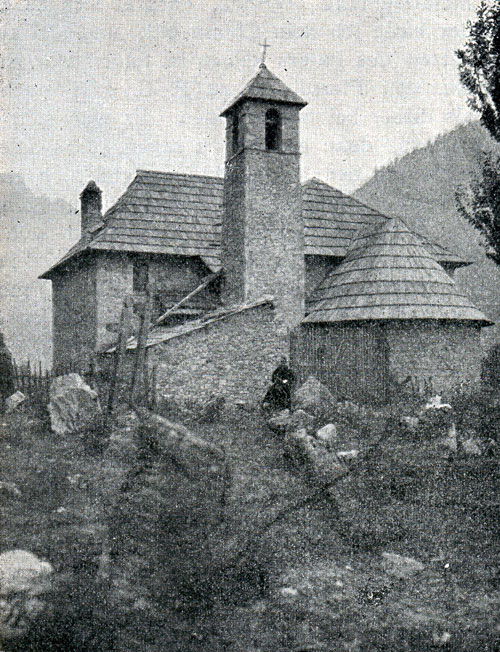

I crossed the little (1 m. wide) bridge over the river and, continuing along the left bank for a quarter of an hour, I reached the church of Theth in Nrejaj. It is quite a large building. The main floor comprised the church, or rather the chapel, itself and two storage rooms. The upper floor consisted of three rooms and a kitchen that were used by the missionary. The building is situated on flatland and is surrounded by cornfields. There are also a few other houses around it.

When my guide and I got to the church, we found the door locked, and there was no one there to answer our calls. From a passer-by, we learned that the priest had gone to Abata to visit a colleague for a few days. While I was wondering what we should do, a young man came around and introduced himself as the church custodian and representative of the missionary. When I explained that I had come to see the missionary, he let us in, stating that the priest would certainly have no objections. I dismissed my guide and gave myself to the care of the custodian, Pjetër Gjoni. Pjetër was a crafty devil. One should not be led to believe that, by inviting me in, he was acting out of Christian charity. He was already calculating how much more he could make out of me than by slaving away in the fields.

Theth is marked on the maps as a settlement, but this is not completely accurate. It is more of a region. The valley of the Shala River from its source southwards down to the Qafa e Boshit (Bosh Pass) is the territory of the Shala tribe. At Ndërlysa, the valley is interrupted by a ravine several kilometres long through which the river makes its way. The area north of the ravine, the region of the river's source, is called Theth, and the area to the south is known as Shala e Madhe (Greater Shala), or simply Shala. Although both areas belong the Shala tribe, they live more or less separated from one another and do not regard one another as relatives. Marriages between the two halves of the tribe are thus allowed. Each of the areas has its own missionary. The one in Theth resides in Nrejaj and the one in Shala resides in Abata.

Theth comprises the following seven hamlets, 90 houses in all: Nrejaj, Markdedaj, Gjeçaj, Nikgjonaj, Okol, Leçaj and Ndërlysa. One is wont to calculate seven souls per household, but for some villages and areas this gives erroneous results because, due to the patriarchal customs of the Highlanders, whole extended families can live under one roof. Even if there are several married sons in the family, none of them leave home to build a house of their own. They all continue to live together. In some cases, fifty people can be found living under one roof. It is obvious that such circumstances do not promote proper sanitary conditions. Syphilis is particularly prevalent. Until quite recently, this dreadful scourge was unknown in the Highlands. It was brought in from Shkodra five or six years ago and spread rapidly, promoted by the customs and living conditions of the Highlanders but also by a lack of knowledge about the way the disease is spread. Nowhere have any precautionary measures been taken, not even the simplest.

The people of Theth are active in herding and farming but the proceeds of the latter activity are not sufficient since there is too little farmland available. The crops consist almost entirely of corn, which is processed at the watermills, of which there are several in the valley. The main food staple is corn flour, and what is lacking is brought in from Peja because it is cheaper there than in Shkodra. Every week a group of villagers from Theth and Shala sets off to get flour which they carry on pack animals or on their own backs. Because of the difficult mountain terrain, the only pack animals used in the valley are mules. They are astoundingly sure-footed and can clamber up difficult rocky slopes like chamois. There are no horses to be found in the Shala Valley, or in the neighbouring areas to the east and south.

With Pjetër's assistance, I was put up at the home of the missionary. Theth makes a very pleasant stay in the summer as opposed to most other parts of northern Albania. The heat is not so intense because of the high elevation (780 m.) and the surrounding snow-covered mountains.

The next morning (August 11th), the bajraktar of Theth, Sokol i Marash Nikës, came around to see me. He was about fifty years old and had a friendly expression on his face, that was marked by the years. We had a very interesting conversation, during which Pjetër made lunch in the adjoining kitchen. Pjetër suddenly came back into the room, informing us that he had slaughtered a chicken but had no idea how to cook it. I went into the kitchen, followed by the bajraktar, and altogether, we manage to make a palatable meal out of the poor bird. As compensation, I invited the bajraktar to lunch and we had a splendid time of it. Pjetër had found plates, knives and forks in the missionary's cupboard, not only for me, but also for himself and for the bajraktar. I was highly amused to observe the difficulties my companions had with the utensils with which they were not familiar. After some time, the bajraktar threw the knife and fork aside in a huff and used his fingers, as his forefathers had done.

After lunch a woman and a girl came in to speak with the priest. The woman must have been quite beautiful in her day and her girl was quite attractive, too. In fact, one encounters many a fair maiden among the Highland women. Coarse peasant faces that we are used to seeing in our country are extremely rare in Albania in both sexes. We invited the women to sit down for a while, and such a warm-hearted conversation arose that I felt quite at home, as if I were in an Austrian farmhouse. The bajraktar and Pjetër took advantage of the occasion to consume great amounts of the tobacco that I had brought with me from Shkodra. The Highlanders love to smoke. Even the women smoke.

The women of Theth in festive costume

(Photo: Shan Pici, 1938).

The life of women in the mountains is radically different from that of women in town. They are all treated with great severity. Once they are fourteen years old, girls in town are almost never allowed to leave the house. In the Highlands things are different. No one stops them from taking long walks alone in the mountains. Marriages in town are almost always arranged by the parents, and the couple often only see one another on the day of their wedding. Because contact is not impeded in the Highlands, couples sometimes get married because they are in love. If a boy is attracted to a girl from a neighbouring tribe - the Highlanders do not marry those whom they regard as their blood relatives - he visits the house in question on numerous occasions. Then, he sends his mother or another relative with a present for the girl's father. If the father accepts the gift, it means that he has agreed to the engagement. If the father refuses, but the girl wants to marry him, the boy will abduct her with the help of his friends, but he then becomes the object of a blood feud. Women are quite often abducted with their consent.

Brides have no dowry. What is more, before the marriage, the bridegroom must pay the bride's family a sum of 1,100 to 1,500 piastres, according to his financial situation, 3,000 piastres at the most.

Despite the efforts of the missionaries, polygamy is quite common in the Highlands. In some cases it is required by custom. If one of two married brothers dies, the other brother is required to take the widow as a concubine. This also applies to an uncle's wife.

In the afternoon, Pjetër and I visited the open graveyard beside the church which is full of big wooden crosses in the shade of large trees. We were sitting around on the grass with several men who came around, smoking and talking all the time, when someone approached with a spade and began digging a shallow grave next to us. He then fit the grave, half a metre deep, with boards and made a sign to several women who were waiting in the distance. One of them carried a little cradle with a dead baby in it. She took the baby out and gave it to the man. He lay the small corpse in the grave, placed a board upon it, and covered it all with soil. The mother then placed the cradle upside down on the grave as a sign that there was no more need for it. The whole event took place in silence without any sign of emotion, with the exception of a few tears that welled in mother's eyes when the soil was thrown onto the improvised coffin. All the time, we were sitting just a metre away, talking and laughing, and even the gravedigger joined in on our conversation [...].

[Two days later] in Nrejaj we finally met the missionary, a Franciscan, together with his mother and two sisters who had come to the vicarage to keep house for him. The reverend gentleman was still quite young, just over twenty, and was not well versed in the customs of the Highlands. He had only been transferred here from his native Shkodra six week ago. His inexperience was a major reason why my travel plans were thwarted. His name was actually Father Lodovico, but the Highlanders prefer very short names. The names they are baptized with are all monosyllabic, such as Kin, Kol, Lek, Nou, etc. He was thus informed when he arrived that they did not like his name and that they would call him Father Gjon. The people of Theth put up with no contradiction in such matters. The priest of Abata had to undergo a similar metamorphosis, too. Father Cyrill became Father Deda.

The two sisters, fourteen and seventeen years old, were the first girls from Shkodra that I had occasion to meet. Their names were Age and Leze and they were both pretty, indeed the elder one was quite attractive. Initially, they were rather shy in the company of men they did not know and only opened up a couple of days later. In my presence, even when we ate together, with me being the guest of honour, they did not dare to say a word. On one occasion, when I got up to get the bottle of water at the other end of the table, there were cries of consternation. It was unheard of that I, as a man and thus a lord and master of creation, should deign to do something that was the job of the girls. Whenever I lit a cigarette, one of them was always on the spot with a burning matchstick in her hand. From these examples alone one can see the subordinate role that women play, even in better urban families.

Church of Theth

(Photo: Erich Liebert, 1904).

The next evening I told the priest where I intended to go next on my journey and asked him to find some reliable men to take me to Peja. As most reliable he suggested Pjetër, whom I already knew, as well as Zogu, the son of the bajraktar, and two other men that I did not know - Sokol i Marash Ukës and Sadri Luka. The first three lived in Nrejaj and the latter in Okol. He offered to discuss the matter with them. He did so the next morning and informed me that the first three were willing to take me to Peja for an appropriate wage. The fourth, Sadri Luka, was unavailable but would be back the following day. Since the priest told me that Sadri Luka was the most intelligent of them all and was feared because of his dauntlessness and temerity, I resolved to talk to him before making a final decision. Another aspect of my decision was the fact that Pjetër and Zogu had said that they would not take me over the trail to Gusinje but would try another side route through the mountains. Gusinje, isolated and surrounded by high mountains, was notorious for its xenophobia and insolent behaviour, Aside from this, the area was up in arms because the Turkish government was trying to introduce taxation. Even Albanians from Shkodra who had business there had been threatened and could only move about in Gusinje in the company of respected local men. There was thus good reason for their suggestion to take me on a different route. However, I was particularly keen to visit this area that few Europeans had ever seen and did not want to give up my original plan.

The next morning I discussed the issue with Sadri Luka who was an intelligent and agile fellow. He sat smoking his cigarette and said nothing for a while. Then he replied: "The tour involves certain danger, and the more people involved, the more danger there would be. The attention that a group would cause would inevitably lead to violence. It would be better to try and get there with one guide.” He stated that he would get me there and would take me right through the middle of the bazaar of Gusinje and Plava.

This was the man I was looking for! The serenity with which he spoke and the carefully considered remarks made about my trip gave me the impression that, with his support, my project could more likely be brought to fruition than with the other three, i.e. the triumvirate. The others were no less sly and daring, but seemed not to have thought the project through and seemed to rely on brute force alone. As payment for his services Sadri Luka demanded the wage that I had promised to the other three men together, and I agreed. We arranged that I would go to meet him in Okol in the afternoon to discuss the details. Pjetër and his companions were not to be informed because they would be up in arms when they discovered that they had been left out of the deal.

But they were not to be deceived. They were suspicious at the long talks I held with Sadri, all the more so when Sadri had departed, when I gave an evasive answer to their question about the journey. Pjetër declared that they would in no way accept being sidelined. When I countered that I had not come to a final agreement with anyone and that, at any rate, I was the one to decide who accompanied me, he seized a crucifix on the missionary’s table and swore that I would never reach Gusinje alive with Sadri.

This was not simply bravado. His companions and Sadri had long been on bad terms, and Pjetër himself was in a difficult financial situation that he hoped to overcome with the help of my wallet. To get out of an earlier blood feud, he had sold all of his Martini rifles and now only possessed one muzzle-loader. He desperately needed to buy a new Martini. I had lent him mine on our excursion up to Maja e Drenit.

The issue was becoming more and more complicated and I was curious to see what Sadri would say about the new turn of events. However, before I could go and see him in Okol, I was obliged to accept an invitation, with the missionary, for lunch with the bajraktar at his summer cottage. His house was situated on a slope of the Maja e Lisit, three-quarters of an hour from the church. The cottage was built of twigs and branches and was inhabited by the whole family. When I arrived with the missionary around lunchtime, preparations for the meal were already underway. We first sat down on a heap of leaves and the bajraktar made us the usual coffee and invited us to partake of his fresh green tobacco. Lunch was served on a low round table as is custom throughout the Orient and we sat around it cross-legged. There were no individual plates. We all ate out of the same bowl. Boiled mutton stew was the first course that was served with delicious cornbread. The second and final course consisted of mazë, a speciality of the Highlands that is only served on exceptional occasions. This is a corn-flour porridge made with water over which cream is poured.

If this was a festive meal offered by one of the leading men in Theth, one wonders what it would be like eating with the average Highlander. The staple food they consume are crusts of cornbread boiled in saltwater and then eaten dry. The better-off can afford cheese or sour milk diluted with water. What a miserable state of affairs! When will the time come for this highly intelligent people to be able to live a decent life?

The bajraktar accompanied me a ways down the trail when we left the cottage and the conversation turned to my coming departure. He, too, insisted that he would not allow me to be guided by Sadri and declared that I would never make it to Gusinje with him. The matter was now very serious because the bajraktar was an elderly gentleman, and everything he said was well considered in advance. He appealed to me to talk to Sadri so I hastened to Okol with the missionary and a young boy who was with us. We arrived at Sadri’s house an hour later. It was one of the largest buildings in the valley, which showed just how prosperous its owner was. When I explained to Sadri what had occurred and mentioned the oath that the other side had taken, he gave a contemptuous laugh and stated that this was no problem whatsoever. “We are all armed, so they will be just as intimidated by us as we are by them.” I decided that, if Sadri were willing to risk his head, then so was I. We agreed to set off the next morning at dawn and decided what Albanian clothing I should wear. It would have been far too dangerous for me to try and get to Gusinje in my European clothes. The young boy who was with us agreed to take me to Okol before sunrise where Sadri would be waiting for me.

The Missionary of Theth and his family

(Photo: Karl Steinmetz, 1904).

We returned to Nrejaj with a sense of relief and chuckled at the thought of how surprised the other side would be when they discovered that the bird had flow the cage. I prepared my small pack, the boy spent the night at the house, and we went to bed. I am wont to sleep in the cool night air and, as such, I had the bedroom window open. About an hour after midnight I was awakened from my sleep, light as it was before a journey. “Father!” I heard from outside the window. “Father Gjon!” I recognised the voice of Zogu, the son of the bajraktar. No one answered. The missionary was sound asleep. This was followed by some whispering and then more calls. I got out of bed without making a noise and woke the missionary up who was sleeping in the next room. He was petrified. It was very unusual for one of his parishioners to come by at night and risk being shot by a Nikaj from over the border who might be prowling around in Theth or Shala with a loaded rifle. In view of the wild temperament of the people of Nrejaj, I feared violence was imminent. Initially, the missionary wanted to ring the church bell to inform everyone that there was an emergency. After consideration, however, we decided to talk to the men outside first. The missionary went over to the window and asked who they were and what they wanted. It was the triumvirate of the opposite party who asked if they could come in. They could not stand outside for long because of the Nikaj. Neither he nor I had anything to worry about, they added. After a long discussion, we agreed to let them in but not before they gave up their weapons. Each of them handed his Martini through a little window near the door. The missionary carried the rifles into his mother’s bedroom and then opened the door. A great dispute ensued. They had found out about my visit to Okol and surrounded the vicarage that night, observing me make preparations for an imminent departure, and concluded that Sadri would be picking me up that night. They had been observing the house all night, intent on killing both Sadri and me, should we attempt to leave. They also stressed that they had taken leave of their families so as to flee from tribal territory right after the deed, and escape any blood revenge. Since Sadri had not turned up and they were in constant danger from the Nikaj outside, they decided that they had to get into the house to keep a better eye on me.

There was no more question of me departing now. My satisfaction had been premature.

The next morning (August 16th), the church looked like it was under siege. Armed supporters of the triumvirate were pacing around and agitated talks were being conducted here and there. The whole valley was up in arms. The prevailing opinion was that both the missionary and I should be shot so as to put an end to the problem. On top of this, later in the day, Sadri informed us that he was waiting in a house a quarter of an hour away to talk to us. He could not approach the church because this would have resulted in an unbridled exchange of fire. I took the missionary with me and left to go and see him. The men let us through after first ensuring that I had left all my belongings in the vicarage.

We explained to Sadri that the trip to Peja was impossible under the circumstances. He understood what we were getting at, but then put forth his stance in no uncertain terms. It was now a matter of honour for him and he would have to take me to Peja whether I want to go or not! I would certainly have gone with him, had there been any way of smuggling my belongings through the cordon sanitaire, but even if this had been possible and we had gotten over the Qafa e Pejës despite all the uproar in the valley, we would never have reached Peja. Word spreads fast in the Highlands and a barrier would have been thrown up at Gusinje at which not only the trip would have reached an abrupt end. We went back home, pretending that we would do our best to convince the other side and calm them down.

I thus found myself between the flames of two roaring bonfires. Father Gjon advised me to return to Shkodra, but I was not too keen on this because it would have put an end to all my travels in the mountains. I resolved to set out for Abata and get over to Nikaj, and informed all of the men mulling around the church of my decision. Some on them under the influence of the bajraktar consented. Others stated that they would not let me depart for Abata or even for Shkodra because they suspected I would meet up with Sadri on the way.

The missionary, who did not want to damage his relations with his parishioners bent one way and then the other like grass in the wind, agreeing with everyone. I secretly asked the sixteen-year-old boy who was to take me to Okol, if he would accompany me to Abata at dawn the next morning and he agreed.

I had a last look through the window before I went to bed and could see some shadowy figures lurking under the trees. The house was still under observation.

At the crack of dawn the next morning I looked out. There was no one to be seen. I woke the missionary up and said a quick good-bye to him and his family. The brave young lad was already at my side, with a rifle over his shoulder and a cartridge belt around his waist. Unnoticed, we snuck out through the nearby fields and, half an hour later, left the valley of Theth.

[from Karl Steinmetz, Ein Vorstosz in die noralbanischen Alpen (Vienna & Leizpig: A. Hartleben, 1905), pp. 1-32. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP