| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1908

Ekrem bey Vlora:

An Excursion to Berat

Ekrem bey Vlora (1885-1964).

The Albanian nobleman Ekrem bey Vlora (1885-1964) visited the Berat region of central Albania in 1908, the end of the Ottoman period, and noted his observations in a diary. This diary, from which the following extracts are taken, was later published in book form in German as “Aus Berat und vom Tomor: Tagebuchblätter” [From Berat and Tomor: Pages of a Diary], Sarajevo 1911.

Carl Patsch has already written about Berat in the ancient period. Since there has been no new material since that time, and in particular no new monuments discovered, I have nothing to add to his work. I will therefore omit that period and concentrate on periods not dealt with by him.

One day is sufficient to see all the remains of the past of Berat. The most spectacular among them is the fortress, now completely defenceless. There is a nice road, possibly once used by carriages, that leads from the Atik Quarter up to external gate facing southwards.

The site is perfect for a fortification. It dominates the whole valley of the Berat River, including the Sinja [Sinia] and Sqepur [Skiepuri] Passes. The walls form an irregular, very frayed triangle, each side of which nestles into the terrain optimally for defence. Time and human beings have wrought much destruction such that the original fortifications can no longer be appreciated. Tradition has it that the citadel was constructed by Michael Comnenos, the Despot of Epirus. I would only note that the style of construction is undoubtedly Byzantine.

There is a legend attached to this fortress, one of the many about a human sacrifice. The walls would not stand. They collapsed each time they were built. The constructor, a local prince, turned to a magician to find the cause. He responded that the walls would only hold if they were built on top of a woman’s body. A dead woman was then buried in the foundations, but to no avail. Another woman was subsequently walled into the building alive, but this did not help either. Finally the wise men of the country interpreted the magician’s words as follows: a woman still breastfeeding her baby was to be walled in alive under the outer tower over the river down to which an underground passage led (the passage is still mostly intact today). A hole was left for woman’s breast so that the child would not die of hunger as it grew.

View of the Mangalem Quarter in Berat (photo: Robert Elsie, March 2008).Mention is often made of fortresses and mediaeval wars in this part of Albania, but we know virtually nothing of the Turkish period. It was custom in Turkey, perhaps adhered to consciously, that there be no or few inscriptions or archives that could bear witness to the past. All searches for epigraphic evidence have failed. Only on the first gate did I notice the following letters in red brick four metres above the ground, but I do not know what they mean.

X † K

MThe fortifications are at any rate in ruins. Only the first courtyard with its monumental gateway and the wall along the riverside are well preserved. One can reach the latter easily on the bastions and ring walls, the parapets of which have collapsed. A Turkish flag waves in the wind on a barren terrace at the extreme north end. From here, 100 metres over the river, one has a splendid view. To the north is the valley of the Berat River and the Dumre [Dumbre] and Sulova Mountains. To the south is the whole town with the narrowing of the river and the beautiful stone bridge of Gorica [Gorítza] and the hills of Mallakastra [Malakastre]. To the west rises Mount Shpirag [Schpiragr] surrounded by a garland of beautifully situated villages and culminating in the Sinja Pass and the Divjaka [Karatoprak] plain. To the east are the mountains of Skrapar and the huge ridge of Tomor, the peak of which is always wrapped in fog. From here, Berat looks much like a town in the Alps, rather like Graz, the pearl of Styria, as seen from the castle. It makes a wonderful impression from a distance, as do almost all Albanian towns, but, like all Oriental settlements, the traveller is disappointed when he enters. Such is Berat, a large, well-situated Turkish town that has nothing individual to it. It is simply a hundred times larger than a village of one hundred inhabitants. The difference between settlements in the Orient is not qualitative, but simply quantitative.

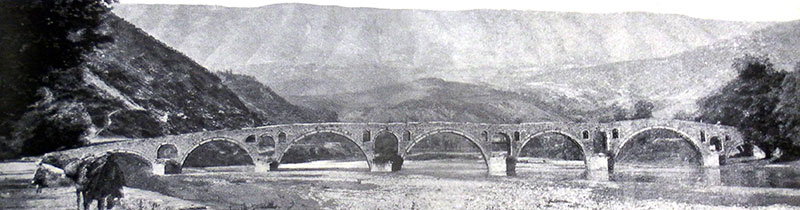

The Gorica Bridge (photo: Ekrem bey Vlora, 1908)

The Gorica Bridge (photo: Robert Elsie, November 2010).The foundations on which the fortress was built have not been damaged very much, probably because they were rarely attacked from this side. Crowned by towers of beautiful architectural form, they plunge vertically to the river below. In the entrenchments there are still many cannons left over from the past, because the Serasker, Reshid Pasha (1835-1838), besieged the opponents of the Tanzimat here. The fortress was torn down after it was given up.

I could distinguish artillery from three different periods. The oldest were of cast iron and seemed to be of Venetian origin. They were probably brought here from the fortress of Vlora, Other cannons, smaller ones, have inscriptions on them saying “Seid Ibrahim Pasha, son of Kaplan Pasha. May God allay all things, 1217 (1801 AD).” They were cast at a time when the beys of Vlora were largely in power here on a hereditary basis. The third type come from the Tophane in Constantinople and are more recent since they have imperial Tughras on them.

The ruins of the palace are to be seen on a raised square known as the Hükümet. It was here that the pashas of Berat lived until 1815. On the town side there is a half-collapsed minaret and in the centre is the entrance to a huge and still well preserved cistern. A stone staircase leads down to it. Despite neglect, the reservoir still has half a metre of water in it. Nearby is the one-time jail. It is now used as an arms depot. Piled on top of one another are pipes, wheels, gun carriages of various kinds, and shells of various calibres.

The new armory is situated below the fortress wall, above the Murad Çelepia Quarter. The building is in ruins and is guarded by two soldiers in rags. There are 5,000 Mauser rifles and ammunition here for the taking by any revolutionary movement. But could such a movement ever arise here? At any rate, the authorities seem to know who is who in town because they are so trustworthy.

Inside the fortress there are several hundred houses and ten churches which constitute the Kalaja [Fortress] Quarter. All the buildings seem to be new, with the exception of the churches. Traditionally, the inhabitants here stem from Arberia, the mountains south of Vlora, and probably moved here when the Vlora family were serving hereditarily as mutessarifs of the Sanjak of Berat.

We proceeded to the residence of the Metropolitan. In the absence of His Grace, we were received by his deputy and several priests. After a few minutes, they led us to the cathedral, which has been almost completely reconstructed. Along the entrance wall is a row of statues that make up a sort of portico and come from ancient Apollonia, the present-day town of Pojan, as do the beautiful busts that have been walled into the façade of the nearby Greek school.

Inside the church I was particularly intrigued by the pulpit and the oratory. They are true works of art with wood carvings in walnut. The figures on them are so lively and finely wrought that we were speechless in front of them. Unfortunately, no one could tell me where they came from. This is normal as the clergy here has no great education. I imagine that they come from the earlier metropolitan church that was situated near the above-mentioned Hükümet Square before the great earthquake of 1852. They seem to be of Byzantine Albanian origin. The two paintings on wood to the left and right of the altar niche, one being Christ and the other Mary, seemed quite old and were not devoid of artistic value. They are said to stem from the Church of Ballsh [Balscha] in Mallakastra. We were also shown an urn with the bones of the two martyrs of Berat, Saint Gorazd and Saint Angelar.

I was deeply saddened by the ragged appearance and lack of education of the priests, as well as by the way they handled the treasures of the church, but I was not surprised. These men are supposed to be the intellectual leaders and advisors of the common people, but how are they to lead if they themselves do not understand the most elementary things about culture? The Greek Orthodox clergy in Albania is incredibly ignorant. They are all open to bribes and are all unscrupulous. I do not wish to go into any further details with examples and I certainly do not wish to convey the impression that I am hostile to their beliefs (that are foreign to me) on grounds of religious intolerance or fanaticism. It is enough to say that in 1904, because of their behaviour, over twenty villages converted to Catholicism. The same thing is going on this year, 1908, because the diocese, which collaborates openly with the Turkish Zaptieh, has taken everything away from the destitute population. Perhaps they did so in order to shorten the long road to paradise for these wretched people. It can only be hoped that the Greek consuls, who have infinite ecclesiastical and secular power in Albania, and their disgusting Hellenic propaganda will no longer hold the poor people under the thumbs of the Orthodox clergy, with their well-meaning Greek intentions.

Since I have embarked here upon a short discourse on religion, let me add something about religious relations in general in the Sanjak of Berat. […] Religious affiliation in the Sanjak of Berat is more or less the same as it is throughout Albania. Here, as elsewhere, the Christians form one-third of the population, and the Muslims two-thirds. There are no exclusively Christian regions. On the other hand, there are large Muslim regions devoid of any Christians. The following table shows religious affiliation more or less correctly in the four kazas of the Sanjak.

Kaza of no. of villages Muslim Christian altogether Berat 206 52,000 25,000 77,000 Vlora 72 26,000 4,500 30,500 Lushnja 162 18,000 20,000 38,000 Skrapar 104 18,000 2,500 20,500 Total number 544 114,000 52,000 166,000 The Christians are to be found primarily in Myzeqeja [Müsekié]. Almost totally Muslim are Arberia, Mallakastra, the Tomor region and Skrapar. Here there are only a few isolated villages that have remained Christian in part or completely. Among the former are Vërtop [Wertópi] in the valley of the Berat River, Selenica [Selenítza] and Romës [Rómssi] on the Shushica [Schuschítza] River, and among the latter are Tërbaç [Trbátsch], Kallarat [Kalarát] and Dukát in the Acroceraunian mountains.

There are no external differences between the religious groups. The women all dress the same, for Muslim women do not wear the veil here. The custom is not prevalent because of the high level of morality, the constant work the women have to do outside, and the late conversion of Arberia to Islam. […]

There are mosques and churches everywhere, but nowhere did I observe them being attended very much. It would seem that the Albanians only show their religious fervour twice a year. For the Muslims, this happens on the two feasts of Bayram, and for the Christians on Christmas and Easter. At other times, the temples often serve other purposes. In Smokthina-Ramica [Smoktína-Ramítza] I saw a mosque that was being used as the village henhouse, and in the villages of Poroja [Póro] and Vërria [Werría] in Myzeqeja, I noticed that the churches were being used as storerooms for firewood and grain.

The language used for religious services is Greek for the Christians and Arabic for the Muslims. For preaching, Greek and Turkish have now been obligatory for a long time for political reasons, but these are languages that the preachers, being Albanians, do not understand, and of course nor do the faithful. I need not stress that, in the countryside, the clergy of both religions is incredibly ignorant. Rarely can one find a clergyman who knows how to write. All they know how to read are prayer books and religious treatises on the interpretation of dreams, with which they have been poisoning their surroundings for years, in particular because they are also responsible for school education in the villages. They are the reason behind the infinite ignorance and brutality of the population. Since the priests (of both religions) are considered the most educated men in the villages, they have great influence in local assemblies. It is evident that such men pursue their own personal interests and, for this reason, the Christian clergymen support the propaganda that props up their reign, and the Muslim hodjas support the government. They thus sow the seeds of discord and fanaticism and set the people against one another. It must also be noted that the Orthodox metropolitans are Phanariot Greeks who can, of course, be seen as vanguards of Hellenism. A few years ago, endeavours were made in several Christian parishes to have the Phanar appoint national [i.e. Albanian] clergy, but nothing came of it.

It is interesting to note that the Orthodox Christians do not have the right to have church bells, something they greatly long for, and rightfully so. […]

It is laudable to note that some Albanians, followers of the nationalist tendencies of the nineteenth century, have endeavoured to create a written language. For this, they used the alphabets that they knew from the foreign languages they spoke. The greatest achievements were made by Gregorius, Bishop of Euboea around 1830, who translated the New Testament in Albanian, and Konstantin Kristoforidhi, a teacher at the Greek school in Elbasan, who wrote a grammar and a dictionary of the Albanian language. The result of this was that more and more people began demanding national [i.e. Albanian-language] schools. This was particularly evident in 1875-1880. It was in this period, noted for the Balkan movements that preceded the Russian-Turkish war, the Treaty of San Stefano and the Congress of Berlin, that the Albanians, after almost four hundred years of division since the time of Scanderbeg, managed to draw the attention of Europe to the fact that there existed one unified Albanian people. However, as always, they lacked support from the Powers. Their wishes remained unheard and, after brief resistance, they were forced to resign themselves to their fate. But the movement did bear some fruit. The newly opened Turkish parliament has allowed the Albanians to have a nationality, an alphabet and schools. Naim and Sami bey Frashëri were given the task of choosing an alphabet. Naturally, they decided on the Latin alphabet, with a number of extra letters taken from Greek and Serbian. It was to be used thereafter in all schools. However, it soon became evident that the movement did not have its roots in the people, but was being promoted simply by a few intellectuals. The population remained indifferent to the idea of opening national schools. The means of opening them were also lacking because the rich did not want to devote their wealth to them and the mass of the population had no money. The Averoffs and Chapas and other philanthropists of Albanian origin had left immeasurable legacies to the Greek cities of the Kingdom, but no one had anything to give to Albanian national schools. Only in Korça did the wealthy citizens found an elementary school for boys and girls. However, it was closed down in 1903 under an Albanian governor who had earlier been a member of the nationalist movement. Albanians in Ottoman public service were sceptical about the whole movement. When the Turkish parliament came to an end, permission for the use of the Albanian alphabet was de facto, though not de jure abrogated. The population never knew about the existence of such a right anyway, and therefore did not react to the ban. […]

In 1903 two battalions were ordered to Vlora [Valona] by persons of high authority, to carry out house searches. The result was pitiful: a postcard written in Albanian was found in a lady’s dress. This earthshattering discovery led to the banishment and imprisonment of 80 notables from the surrounding region. At the same time, there were over 100 murderers living freely in their homes in the mountain regions of the kaza.

No one is spared. For so-called political crimes, a brother can be arrested for a brother, a son for a father, a wife for a husband, even friends and bare acquaintances are taken to task. In September 1904, I saw 60 such wretches locked up in the cellar of an inn in Berat.

It is evident under such harsh conditions, that the idea of national schools has not made much progress. I think that there will only be a reaction in the future if the present pressure is kept up longer. The southern Albanians are indolent by nature. They are devoted to material gain and to the fulfilment of their personal desires, by whatever means. They will only rise in revolt when the cup is overflowing, more so than with other peoples. Chaque people a le gouvernement qu’il mérite, as the saying goes. This is also true for the Albanians. […]

It is amazing how many great men this small nation has given to its foreign rulers. In Turkish history, over the last 350 years, there have been no less than 36 grand viziers and over 100 grand masters of the janissaries who were of Albanian origin. Greece owes to the Albanians the most important figures of its struggle for liberation, and the small Albanian colony in Italy provided two popes and gave the Kingdom of Italy a man like Crispi. It is hard to believe that in Turkey and Greece, almost all the high offices are held by Albanians. The Viceroy of Egypt is also of Albanian origin. Mehmed Ali Pasha stemmed from a poor family from near Korça and moved with his father, a tobacco merchant, to Kavala, from where he reached Egypt and took power with the help of some compatriots he had hired. […]

According to the regulations valid for the whole Sanjak, the language of instruction for Muslim schools is Turkish and that for Christian schools is Greek. As such, pupils are taught in both school systems in languages that they do not speak at home. As a result, they do not succeed in learning properly. The words and sentences they are forced to learn by rote are soon forgotten.

Officially, there are many Turkish schools in the Sanjak. In actual fact, however, only the following ones exist: In Berat there is an unfinished idadiye (senior secondary school) that opened eight years ago, a ruzhdiye (junior secondary school) and several ibtidaiye (elementary schools). In Vlora there is a ruzhdiye. The other kazas, Lushnja and Skrapar (with its capital Zriz [Çërica]), and the villages of Kapinova [Kapinówa], Kúta (district of Berat), Smokthina, Dukat, Tragjas, Hoshtima [Hoschtíma], Kudhës [Kuds] and Kanina are said to have elementary schools. However, in Kapinova no one knew of the existence of a school and I found the school teacher in Smokthina working as a servant for a rich man. The lack of pupils, of a salary and of a school building led him accepting a more modest profession. […]

We said good-bye to our guides and followed the ruins of the fortress walls down to the Murad Çelepia Quarter in order to return to the town on that narrow path.

Murad Çelepia is of recent date. There is nothing of historical interest except a rectangular tower made of rough limestone blocks that is probably over 30 metres high and seems to have been a watch tower in the early Turkish period. It now peacefully bears a clock, as does a similar tower in the town centre.

Aside from the ruins of the old home of the Vrioni [Virjoni] family, there were about fifty poor huts. They are inhabited by the African colony of Berat. These are the descendants of slaves whom Omer Pasha Vrioni brought back from Egypt and later released. These groups of Africans, particularly when they are numerous enough, have a special women’s clubs. Every Friday they meet in a particular café to perform their gulum. The performance begins with the women sitting in a circle where they howl, scream and shout to the rhythm of a large and a small oval drum called a dymbelek. Upon a sign given by their leader, the godje, they throw themselves upon the floor, and roll and jump around. Once a year, on Hidrelés Day (the feast of Saint George, 23 April, old style) the gulum is performed in public before an audience. I had the impression that the screaming and music of the women was so hypnotic in effect that they completely lost control of their senses. The custom is disappearing in Berat since there are less women to perform it. The children arising from mixed marriages no longer do so.

The main trail from Murad Çelepia passes a group of graves with three now empty mausoleums of one-time pashas of the town and the burial place of Baba Ali. The people say that he will not put up with a roof over his grave, that he goes out wandering in the night, and that he carries out ritual washings. For this reason, there is always a jug of water at his feet. […]

Our path led us to the bridge that crosses the Berat River to the suburb of Gorica on the left bank. It was constructed by Kurd Ahmed Pasha in 1780. It is high and thin, with an uneven surface and a particularly steep main arch. Its construction is not particularly unusual. It is typical of the normal type of bridge construction in Albania and on the peninsula that consists of putting as little pressure as possible on the arches and reducing the lateral pressure that has an impact on the pillars. The keystones of the vaults are often part of the very surface of the bridge and the roadway sinks to the pillars, only to rise with the next arch. The pillars have open niches in them that give the bridge a light impression.

Despite its young age, it is remarkable that this bridge is also linked to a saga of human sacrifice. It is said that the pillars would not stand. Kurd Ahmed Pasha asked the scholars of his day what the reason for this could be. They informed him that evil spirits were demanding a human sacrifice. A woman was then walled into a small chamber in the bridge where she died of hunger. The people still point out where the chamber was. In the first pillar one can see, just above the waterline, a grated window that casts a bit of light into a little chamber.

According to what is said, Gorica is a new settlement. Only the Church of Saint Spiridion seems to be old. Clustered around it are houses inhabited exclusively by Christians.

From Gorica there is a road to Velabisht [Welabíscht] that was originally intended to lead to Vlora via Sinja. Here in Velabisht one can see the ruins of a mosque, a tekke [dervish lodge] and a palace with ancillary buildings. They stem from the time of Ismail Pasha who was Lord of Berat in about 1760. This was his favourite place of residence and is named after him. He stemmed from a poor family that lived in the village of Konizbalta [Konisbált], near the Hasan Bey Bridge. He was taken to Istanbul in about 1732 by the son-in-law of the Grand Vizier Köprülü to serve as an imperial page. There he gained favours and honours and, since there were only underage children in the Vlora dynasty, Sultan Mahmud I invested him with the position of Pasha of Berat. Here he made himself unpopular because of his cruelty and arrogance. It is said that, as he was considering moving Berat to Velabisht, he was murdered in his palace by the local people who were furious about the intended move. It is true that he died a violent death, but fate did not reach him in Berat but in Vlora where he was murdered in the house of the Ahmed Agali family, in the presence of the agas of the town who had gathered there. He is said to have attempted to abduct and marry a widow of the Vlora family who lived in the castle of Kanina. They still sing a folksong about the event. His grave is preserved in Vlora. As Pasha of Berat, he was succeeded by his steward, the above-mentioned Kurd Ahmed Pasha.

We now turn our attention to the centre of town, the shehr. It is quite beautiful in parts, but has no buildings of particular historical or architectural value. In the Tek-Dridhen-Qerret Quarter is the covered bazaar, the bezistan, an alley full of shops and covered with boarding. The great market in the centre of town consists of miserable and highly inflammable wooden huts that belong to the Vrioni Family and that are held hereditarily in tail on the male side. This is now a rare legal institution in Albania.

In the Mangalem Quarter, almost 60 metres above the river, there is a small chapel dedicated to Saint Michael, Shën Hill, situated on a cliff terrace. It is only open on the occasion of the saint’s feast day. A few metres above it is a grotto, the Grotto of Shën Hill, the walls of which still show traces of the mosaic figures that once adorned it. The place of worship in the grotto is older than the chapel. They both seem to stem from the early Byzantine period.

Houses in the Mangalem Quarter of Berat (photo: Robert Elsie, November 2010).Just as it is rich in Christian churches, Berat is also rich in places of Muslim worship. For the 7,000 Muslims in town there are said to be ten mosques, twelve mesjids [small prayer houses], three larger tekkes and a medresa (theological school) for fifteen pupils. The oldest mosque bears the name Xhamia e Mbretit, the Sultan’s Mosque. It is said to have been constructed by Sultan Bayezid II in commemoration of his campaign in Albania. This is a tradition that contradicts the fact that Bayezid II was never in Albania. More probable is the second version according to which Bayezid II sent his lala (master of the court) to Berat in 1492 to build a mosque. The earliest record of the construction of the mosque tells the following: Bayezid and a few of his men came down from his camp in the present fortress of Berat. There he came upon a shepherd who was grazing his sheep. The sultan asked him for a sheep for his lunch. Like the whole Christian population of the country, the shepherd did not like the Muslims and refused to give him a sheep, in particular since he did not recognise the sultan. Bayezid then asked him for his staff and said, “If I manage to throw this staff and hit the chapel down in the valley, you must give me a sheep. If I do not, I will give you as much gold as the sheep weighs.” The shepherd agreed. God was with the sultan, and the staff hit the cross on the chapel. The shepherd was so impressed that he converted to Islam and, where the chapel once stood, is now the Sultan’s Mosque.

A second mosque is called the Mosque of Omer Pasha Vrioni, after its founder. The names of those who built it are known.

The largest mosque, in the centre of town, is called Xhamia e Plumbit, the Lead Mosque. Also of interest because of its grotesque frescos is the Xhamia e Telélkavet. People say that two holy men are buried in it. They had the dome and crescent constructed of gold so that if the mosque collapsed, it could be reconstructed.

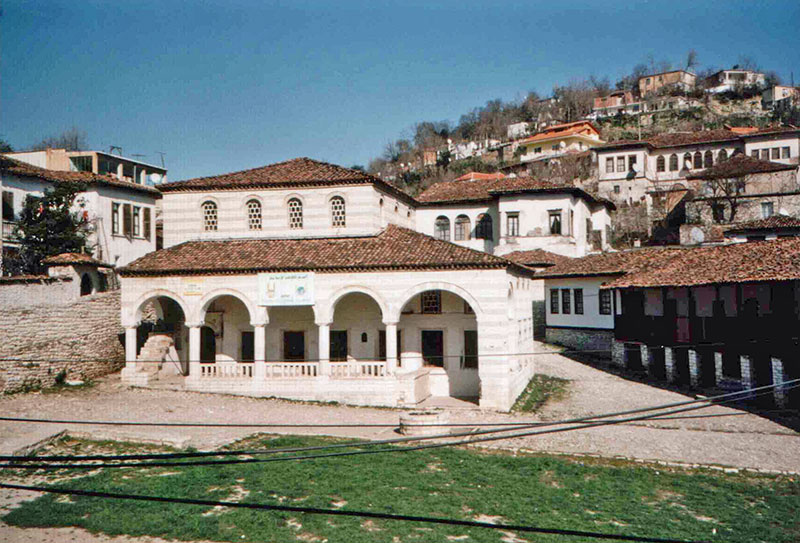

The Halveti Tekke of Berat (photo: Robert Elsie, January 1998).Of the monasteries, we visited the tekke of the present Sheikh Hasan, of the Halveti Order (tekkes are named after their leaders). It was founded by Kurd Ahmed Pasha in 1785 who invested it with much income. Aside from the isolated prayer room, there are a number of one-storey buildings surrounded by low walls in the courtyard. These serve as accommodation for the sheikh and the dervishes. The main building is a six-metre-high rectangular construction made of carefully carved stonework. The side is twelve metres in length. In front of the entrance is a portico, the columns of which stem from Apollonia. The interior is plain. It consists of a large prayer room and a small side room. The finest element of the decoration is the ceiling. When one looks up at it, one is so captivated by its beauty, splendour and taste that one can hardly believe one is in Berat which, otherwise, has little to offer the aesthetic eye. The ceiling is made up of wooden panels in such harmony as one rarely finds in Albania. The arabesques reveal not only purely Oriental elements but also clear western influence. The colours are lively, harmonious and amazingly fresh. I was unable to learn who the creator of this work of art and the tekke was. […]

Ceiling of the Halveti Tekke of Berat (photo: Robert Elsie, March 2008).In the small side room there are two graves: of Kurd Ahmed Pasha and his son Mehmed Qemaleddin Bey. The pasha is said to have been Syrian by birth. What is known for sure is that he came from Prizren to Berat to serve Ismail Pasha Velabishti. As his steward, he was first made Mütesellim (governor) of Delvina and then Pasha of Berat. He reigned blithely in Delvina and Berat for ten years and left behind one underage, retarded son, Mehmed Qemaleddin. He was taken by his sister Meryém, known under the name of Hanko Pasho, to the farm of Ngurrëza [Ngurza] in Myzeqeja and was held prisoner there until Meryém’s husband, Ibrahim Pasha Vlora, was made pasha. Qemaleddin died at an early age and was buried next to his father. It is interesting to note that the two graves are simply little mounds of earth with no edges or markings. The same is true of the graves of the ancestors of the Vlora family in the Tekke of Sinan Pasha in Kanina. Here and there, there are signs of desecration of the graves, either by thieves or tekke guards digging for valuables.

Near the so-called People’s Garden (Milét Bahçé) we visited the largest Turkish school in Berat, the aforementioned idadiye in a one-storey building constructed with public money in 1900. It has three ruzhdiye and two (instead of the usual three) idadiye classrooms. One hundred children are taught here for free because the salaries of the teachers are paid by the Ministry of Education with money provided by the Agricultural Bank (Siraat Bankasi). […]

In the courtyard of the school stood several ancient monuments that were all taken from the foundations in the fortress near the Hükümet Square. The most important of them was a limestone sarcophagus with the figure of a man in a pleated Greek toga on the lid, and the following inscription:

ΕΙΒΙΔΙΟΣ ΝΕΙΚΑΙΣ Ε

ΤΩΝ ΜΔ ΕΠΟΙΗΣΕΝ Η

ΣΥΜΒΙΟΣ ΝΕΑΠΟΛΙΣ ΕΚ

ΤΩΝ ΑΥΤΟΥ ΜΗΝΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝI also saw bits of a Doric column and a small limestone altar similar to the ones found in Apollonia-Pojan. It had a badly shaped cross on the front side, on top of an old, illegible inscription. The damaged bust of a young woman was cemented into the school wall.

As a parallel to my visit to the Turkish idadiye, I also visited the main Greek school. This gave me an opportunity to check up on the efforts being made by the modern Hellenes to civilise the wild and savage Albanians. My guide was the Greek consul.

The school is in a large, rather dilapidated house in the Mangalem Quarter. It is the equivalent of a six-grade secondary school. In addition, Berat also has eight Greek elementary schools – four for boys and four for girls. The secondary school has been around for over thirty years and is the first establishment of its kind to have been built in the Sanjak of Berat. Seventy to eighty boys are taught here free of charge since expenditures are covered by the Association for the Spread of the Greek Language in Athens. The teachers are mostly appointed by the Metropolitan and are also paid by Athens. The church has imposed a sort of tax on the population at a level of 10 piastres (2 crowns) annually, which the subashi collects, often only from among the wealthier citizens. It is to pay the salaries of the priests, but much of it finds its way into the treasury of the Greek school association in Athens.

I must admit that the teaching in this secondary school and in the other Greek state schools is in every way better than in the Turkish school. The Greeks have been working assiduously and devotedly for decades, following fixed principles, with the intent of denationalising the people. Anyone who is not convinced of my interpretation of the intentions and effects of this “civilising and religious” work should come to Berat in the evening when the children – all of whom are Albanians – get out of school, while singing the Greek national anthem.

[Extracts from Ekrem bey Vlora, Aus Berat und vom Tomor: Tagebuchblätter (Sarajevo: Daniel A. Kajon, 1911), p. 24-54. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP