| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1909

Gabriel Louis-Jaray:

Travels through Kosovo and Northern Albania

The French travel writer Gabriel Louis-Jaray (1880-1964) travelled through Kosovo and Albania in 1909 and was in Albania again in August 1919. On his first voyage, he set out from Skopje, a large town which then had an overwhelming Albanian majority population, for Prishtina and Mitrovica. From there he continued to Peja and Prizren and, crossing the famed Vizier’s Bridge, rode through the backcountry of Luma and Mirdita down to Shkodra and Bar (Antivari). From Bar, he sailed to Durrës and Vlora and returned to Skopje. Louis-Jaray’s travel descriptions of Albania, illustrated richly with photographs, appeared in two books, “L’Albanie inconnue” (Unknown Albania), Paris 1913; and “Au jeune royaume d’Albanie: ce qu’il a été, ce qu’il est” (In the Young Kingdom of Albania: What is Was, What it Is), Paris 1914; as well as in a number of articles that appeared in Revue des deux mondes, Revue de Paris, Correspondant, Revue politique et parlementaire and Questions diplomatiques. The material from the articles was republished in the shorter volume “Les Albanais” (The Albanians), Paris 1920, at the time of the Paris Peace Conference, when Louis-Jaray made it clear to his readers that there was no point in backtracking on an independent Albania. The following are excerpts from his journey through Ottoman Kosovo and northern Albania in the summer of 1909.

Mitrovica

In the region of Kosovo and Gjakova [Diakovo], the main towns are constructed around the plain, at the exits to the valleys. The houses in the outskirts are situated on the initial foothills of the mountains or at the exits to the gorges that the rivers have cut through the limestone massif. Peja [Ipek], for example, is located where the Bistrica comes out of the mountains. Gjakova is situated at the foot of the Gjakova highlands at the confluence of a multitude of streams. Prizren is found at the exit of the valley of the Bistrica of Prizren, not far from the gorge of the Drin. The same can be said of Mitrovica. Its barracks that one can see shining in white in the distance, crown the final foothills of the mountain range of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar. The town stretches at the foot of the hills along the Ibër [Ibar] River which is spanned by only one bad wooden bridge. The town would seem to guard the entrance to the valley. The Turks here are always afraid that some Austrian regiment might break through, camped as they were recently in the Sanjak. From Sarajevo to the Aegean, nature has created a number of stages. The plain of Kosovo is the intermediary one between Bosnia and the plain of Skopje. One can pass from one to the other without difficulty. The Sanjak of Novi Pazar is one of the steps on this staircase and access to the next step is commanded by Mitrovica.

"Mitrovica: the natives fighting" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).My initial interest on arriving at Mitrovica was to visit the Russian consul who was expecting me. Unfortunately, he was absent when I arrived and there was no one to replace him. I thus made the acquaintance of the hans of the town. I must say quite candidly that spending a night in one of these hans is pure torture for travellers. It is one thousand times better to take a tent and sleep under the stars. The filth one encounters at the entrance and in the courtyard of such hans is indescribable. The waste water from the building is simply thrown outside anywhere. The rickety stairs lead to rooms that all open onto an interior courtyard. Each of the rooms contains beds with dirty bedding stained by the remains of squashed vermin. The badly carpentered floors, that are never washed, are insulated by a coating of filth from the water used for washing that is simply thrown out into the corridor. The whitewashed walls are the abode of various and sundry parasites. The only lighting is provided by the stub of a candle on the windowsill. The furniture consists of one chair. The filthy and opaque windowpanes are stuffed with greasy paper. One’s first thought is to flee, but alas, one has no choice but to remain. In the morning, the servant came in bearing a copper platter with a towel over one arm and a ewer in the other hand. He offered to pour some water over my hands. I washed my face as best I could with my wet hands and dried both hands and face with the towel. Everyone else washed briefly in a similar fashion. With great difficulty I managed to convince the servant to leave me the ewer of water, the copper platter and the more-or-less clean towel. My personal hygiene requirements astonished the servant and the others around me who were used to the putrid conditions in which the masses of Turks live.

I began my tour of the town with a visit to the kaimakam or sub-prefect, Hajdar bey Lekić, who was already informed of my projects. I asked him for an escort for the following day, which he promised to provide me with. I then took my leave and set off to visit the most interesting Turkish figure in Mitrovica, Javid Pasha. The headquarters of his division was situated on a hill near the barracks, in a new and still quite clean building. His office, furnished in Western fashion, provided a good view of the white and green town cleft by the meandering waters of the Ibër. The sun shone into the room and caused Javid Pasha’s grey eyes to shine. He told me about the campaign he had recently undertaken against the Albanians. He had 1,400 men and three batteries at his disposal, and with this small contingent, he crossed the plain of Gjakova and the region of Peja and burned down the kullas of the chiefs, those fortified towers with walls 60 to 80 centimetres thick that only let the daylight in through tiny windows and slits. He left guard posts behind, and his name was the terror of the Albanians. His action contrasted singularly with the laisser-faire attitude of his predecessors, but Javid Pasha was well aware that it was only an attempt. The kullas would be rebuilt, the Albanians would regroup and he would have to take action again. But Javid Pasha will be there if the external situation of Turkey gives him the opportunity. He concluded: “Get away quickly because I intend to pay another little visit to the Albanians, no doubt this autumn.”

In the bazaar and in the market I purchased clothing, tinned food, melons and bread, etc. for the journey. Not to forget insect powder of which one can never get enough. The owner of the han roasted some skinny chickens for me. We stuffed everything into the bags that my dragoman had made and were ready to load them the next day.

The market place was quite lively and in the evening the streets and alley were full of various people – Serbs and Turks side by side with Albanians. There were Bosnian Muslims who had fled from Austrian-occupied Bosnia and found refuge here while they waited for the government to settle them on neighbouring land. The countryside is farmed by a great variety of races. The old strata of Serb peasants remain. They work mostly as farmers and sharecroppers for the beys and Turkish landowners. In Mitrovica, the largest landowner is the Turk, Fuad Pasha, if I am not mistaken. The harvest is divided between him and his tenants, as I was told, at a proportion of one-third for him and two-thirds for the peasants. In addition to these large estates and farming villages, there are also small farms. These are both the domains of independent Albanian farmers who have come down from the mountains and have acquired or seized land and work on it for their own benefit, or villages of Bosnian Muslims who were settled on fallow land. In this part of Old Serbia, just before the Serbian conquest, the Christian Serbs were hemmed in by the Albanians to the south and the Bosnians to the west.

There are also foreign interests in Mitrovica, represented in particular by the Russian and Austrian consuls. These are the only ones who reside here. The Austrian consulate where I had dinner that evening was a comfortable building, no doubt the most elegant in the region and the best source of information. The consul at that time was Mr Rudnay. The government in Vienna puts its best agents in such observation posts and spares no expense. Balkan information policies are always a speciality of the Ballhausplatz. One has to hand it to them. But the posting here is not without danger. One recalls that a few years ago the Russian consul was shot and killed by a Muslim fanatic who was infuriated at the thought of a foreigner settling in Mitrovica.

From Mitrovica to Peja

Leaving Mitrovica means entering no man’s land. Under the old regime, European travellers never went any farther and could not get to Peja. In Mitrovica, one could only get very vague information, in particular if one wished to continue on to Gjakova and Prizren, as I did. As a precaution, I concluded an agreement with a coachman who promised to get me to Prizren in four days at the most. After long discussions between him and my dragoman, we agreed on fourteen medjide, the equivalent of about sixty francs, which is two or three times the sum that would be required in the West. At five in the morning, my horsemen or equestrian police who would escort me, arrived at the gate of the han. We then waited for the carriage, which finally arrived. I wondered what history this carriage had behind it. It had probably seen its heyday fifty or sixty years ago in Paris or Vienna. It was now a run-down Victoria, archaic in form, used, scratched, mended, and in a miserable condition. However, I was very happy to have it such as it was. It was a rare luxury in such a country. On my journey, I came across other vehicles. They were all of the same format. A board with almost no springs laid out directly on the framework of the vehicle, with the chassis being fixed on the two sides and in the middle. Everyone sits on the board in Turkish fashion and I saw vehicles with six to eight passengers crammed into a space where they could hardly breathe.

"From Mitrovica to Peja: my rear escort" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).We departed with some delay at about six in the morning. Some of my horsemen rode in front of me with carbines over their shoulders. The rest of them followed the vehicle. The road was quite attractive for the first three or four hours. We followed along the Ibër River, through the gorges and up to modest heights where everything was green and fresh. We then left this region to cross the mountains, climbing somewhat. There were a lot of trees, mostly groves of pines. On occasion there were broad chestnuts that offered welcome shade. On our way, we were joined by the postman. He was a young Albanian on a big horse, on both sides of which were large saddlebags. These contained letters for distribution throughout the country. He had one gendarme with him and was delighted to join us because brigands were wont to stop postmen in their tracks. Some of the letters contained money. His appearance gave rise to some confusion. My horsemen loaded their guns, galloped forth and shot into the air. When they had done this, I noticed from the expressions on their faces that it was simply in celebration.

One problem did occur two or three hours later. A shot echoed in the distance as we were climbing through the low forests. I put my escort on the alert and told them to load their guns, but nothing else happened. It may have been some Albanian playing a prank.

By ten o’clock we had crossed the low hills and the ridge that separate the plain of Kosovo from the plain of Gjakova. From there on, the landscape was virtually flat, with few trees. The ground was covered rather with thorny bushes. There were very few houses. We stopped at Rudnik where one usually stops for noonday rest. It was a rundown han where the wind and the rain entered at will. We got water and coffee, and I was then given a garret in which I spread a blanket over the hay to dine separately from the rest of the people there. Our skinny chickens, bread and melons were more than welcome. There was nothing else to be had there anyway. In addition, it was Ramadan and my horsemen were not allowed to eat until sunset. I do not know if they strictly observed the law of the Prophet, but in any case they did not infringe upon it very much.

Throughout the journey I was struck by the differences between the map of the Austrian General Staff and the country itself. It is well known that the best map of European Turkey is the 200,000 scale one produced by the Austrian Staff. One centimetre on the map is equivalent to two kilometres. As such almost all the details could be included for a country virtually bereft of population. But I was surprised to see houses and names of settlements marked on it where there was nothing or almost nothing. For Rudnik, for example, from the map I was expecting to see farms, several houses and several hans, i.e. a little village. In reality there was only one modest hut there where you could buy water, coffee and hay.

"From Mitrovica to Peja: an Albanian country home" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).We resumed our journey at about one o’clock, descending slightly along the plain. The scrub grew higher and higher. Thick dust, of an extremely white colour, covered the road and everything around it. It was a difficult journey under the glaring sun. The countryside looked sad and desolate. The horses were exhausted and plodded slowly, step by step. There was hardly any vegetation left. When we got to a river, that I think was the Istog according to the Austrian map, men and beasts came to a stop. The horses wandered back and forth in the water to drink and rest. We rested in the shade behind the bushes before we forded the river that cut the trail in two. As there was little water in it, this was no great problem and we continued our journey.

The first of the ‘towers’ now appeared before us. These Albanian country houses are distinctive. They are like fortresses – square buildings with thick, solid walls with hardly any windows, but with numerous loopholes. The square towers rise at an angle and provide a good view of the surroundings. They are typical in this country of daily warfare and unforeseen attacks. There is usually little land around the towers and it consists mostly of scrub or branches laid out to form a fence. The real defence is the tower itself. One of the first ones we saw was a virtual castle, complete with trees. In front of it was a graveyard with cut gravestones planted vertically in the soil amongst the bushes. Many of them had fallen over and lay intact or broken. They were like fields of druid stones along the road and around the houses. The local people plodded by and old Muslims meditated there on destiny.

The ‘towers’ became more frequent and there were a few peasants around, two or three of whom were armed. In the distance there was a white dot on the green landscape of mountains to which we were headed. This was Peja hidden at the foot of the mountains at the entrance to a gorge. The sun was setting. It was about five o’clock. Seeing our European-style carriage, a group of soldiers from the barracks outside the town ran over to have a look at us. The horsemen were in rank and file. Finally we made our way into the mysterious town of Peja.

Peja

Our entrance into Peja will remain one of the most curious memories I have of that voyage. The water coming down from the mountains flows in rivers and creeks right through the streets and alleyways of the town, and channels have been dug through private properties, but there are dry paths for pedestrians. The entrance to the town on the road from Mitrovica is different. This route takes you up the very bed of the torrent and the innocent visitor is somewhat surprised to be entering the town by means of a river. Fortunately, it was not very deep at that time of year and, as such, the manner of entry was simply an inconvenience.

"Peja: the market" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).But it so happened that I entered the town at the same time as two other local carriages. I would not have noticed them except that I wanted to photograph them as I noticed that they were hermetically sealed. As soon as we got through the river, my carriage and my escort continued down a narrow alley which served as a bazaar and I suddenly became the focus of all attention. It was almost six o’clock. The sun was setting and all good Muslims were preparing to eat. There were crowds in the bazaar, and thousands of eyes were staring at me from the various shops. Old men crouching on the ground stopped smoking in order to get a better look at me. Albanians and Serbs, merchants and customers, all of them came out to the doorways to have a look. Children shouted and, in the midst of all the crowds, my horsemen had difficulty making room to allow the carriage to pass. From a distance I could hear lively discussions. Everyone had something to say. I noticed their gestures. All stood still as I passed, and all stared at me in curiosity.

It was obvious that my clothes and carriage would draw attention, but not to that extent. What was the reason? It turned out to be a typical example of rumours spread in the Orient, especially in the bazaars which serve as the focal points for gossip in such little towns. They had seen the two other closed vehicles pass, with women in them no doubt belonging to some rich merchant. Then came my carriage. There could be no more doubt about it. In reclusive Peja, an Albanian city par excellence, a foreigner consul had arrived, and he was coming to stay because he had brought his family with him.

It was under such unfavourable auspices that I arrived in Peja. It was the same hostile atmosphere that had led to the assassination of the Russian consul in Mitrovica a few years ago. But Javid Pasha had been there, too, and, as I was told, that very spring he had destroyed ten kullas or fortresses in Peja and about fifty others in the surrounding countryside. Most of them belonged to tribal chieftains, to beys. Another notable change had taken place in the region. Just a year ago, not far from here, a French diplomat had found himself in serious danger simply because he took a photograph. I was now able to wander about town freely without being bothered, although, for safety’s sake, it was better to be accompanied. It was generally agreed that the governor of Peja was an energetic figure with a firm hand, one of the leaders of the constitutional movement. As an Albanian, he had been sent here to pacify the country.

Ismail Haki Bey (or Hakky Bey), the mutasarrif [governor] and commander of Peja (such was the name in Turkish on his calling card and such was the French transcription, he said), was one of the officers of the general staff who knew the West. These men spoke perfect French and knew the major cities of Europe. They were civilised and intelligent, passionate nationalists and devoted Muslims who had carried out the revolution. I stayed with him for two days, having lunch and dinner with him, taking part in receptions for people who came around to see him, sleeping at the barracks which served as government offices, and touring the streets and surroundings of Peja on horseback. After hours of conversation with him in his daily activities, I now had a better understanding of what the new regime was all about and who had set it up. At the international college where they had studied, these men had acquitted a sense of Turkish patriotism and were outraged at the behaviour of foreigners in Turkey, a ‘sovereign state,’ and wanted their country to become a nation like the others. On the other hand, they were determined to maintain law and order and not to tolerate legal privileges. If they did secretly favour the Muslims, it was out of racial solidarity or because the latter were part and parcel of the Ottoman nation. The Muslim religion, for them, was the cement that bound the new state together, founded on nationalism. With regard to religion, they were very tolerant, not at all fanatical, and many of them did not practise their faith much (I saw proof of this during Ramadan). Religion was simply the strongest element of cohesion and solidarity. For this reason, there existed both Muslim separatists and Christian loyalists. These men may have had a secret fondness for the separatists, regarding them as stray brethren, but in political matters, they supported the interests of the empire.

This is what was going on in Peja. Peja was now the Albanian town, par excellence, but this was a rather new phenomenon. It was one of the first conquests of the Albanians when they came down from their mountains and chased the lowland Serbs away. The town had a population of about 5,000 to 10,000, with an important colony of Serbs among them. The latter worked as shopkeepers, moneylenders and servants, etc. With the exception of two or three families of high-ranking businessmen, they were all simple people. All the local nobles and rich people were Albanians. Up until 1908, the town and its surroundings were ruled, de facto, by Albanian beys, and the poor Serbs were at their mercy, fearing some new offense every day. Since 1908, they have been able to breathe more freely. I visited one of the leaders of the Serb colony, Mikael Vasiljević, whom I met with his wife and mother in a cottage with a front garden full of splendid grapevines and with a brook flowing through it. He told me how glad the Serbs of Peja were at the new regime, after such long servitude. Now they had someone they could complain to and, although everything was not perfect, they asked for one thing only: that the present state of affairs continue as long as possible. They were not at all expecting the liberation which was to come a few month later from the Serbian army in co-operation with the Montenegrin army.

Vasiljević took me to visit the Serbian school which was not very far away. About thirty or forty children were learning how to read and write there. The well-trained teacher handed me a picture of a female figure probably representing wisdom, with a sword in one hand and an olive branch in the other. These poor Serbs! It was not the sword that they were brandishing before their masters. Over the figure, in Cyrillic letters, a children had written awkwardly: “Happy journey, Ipek [Peja], 17 August 1909. Administration to Assist Poor Children.” Being the recipient of the picture, I could not leave without giving them a bit of money, of which they seemed to be in great need.

I soon left my gracious hosts to return to Ismail Haki Bey. He had saddled the horses and we rode out, accompanied by an officer and my dragoman, to visit the town and tour the surroundings. I noticed that almost no one in the population greeted the governor. Instead, one could see fear and other emotions on their faces. But there was no opposition and, everywhere we went, the crowds drew back submissively to let our little caravan pass. It was no coincidence that the governor was showing me, a foreigner in European dress, around town at a time of day when everyone was out in the streets, and was paying me honours. A certain audacity was needed to assert the new policies of the regime.

We continued our tour, quite aways from town and Haki Bey suggested that we ride onto the Serbian monastery of Saint Sava. Half an hour later, we could see it enclosed within thick walls. It was idyllically located at the exit to the mountain gorge, amidst trees, streams and springs. We dismounted at the monastery and the oldest monk came out to greet us and offer us, as tradition required, cigarettes. perfumed water and coffee. It was delightfully fresh outside and we very much enjoyed our rest there, without having talked much at all. There was a very old chapel nearby, with ancient flagstones engraved with now hardly visible names and dates. The monks seemed quite oblivious to the riches around them and could give us only vague information. The Byzantine architecture characterised by vaults and lowered domes produced such darkness that it was almost impossible to see anything in the interior. I would like to have stayed here and spend the night, but Haki Bey invited me to sleep at his place and it would have been an offense to refuse his hospitality.

But what a night it was! I mentioned how these palaces of governors are treated, with everyone coming and going. All the paupers of the community lodge here in the staircases and entrances. The barracks served as lodgings for the governor and for military and civilian leaders. On the main floor, soldiers were lodged en masse and in indescribable confusion. The upper floor consisted of a series of offices, each with one, two or three couches along the walls. These often served as beds for the officers or employees who worked there. I was given one of the rooms and, as a special treat, my couched was covered in a four-metre-long sheet of striped and coloured silk gauze, worthy to clothe a ballet dancer. But it was a bed sheet alright, and I wrapped myself in it and settled in for a good night’s sleep. As soon as the light was out, I realised my mistake. An invasion! The spectacle I saw on the walls when I lit the candle was impossible to describe. To get farther away from it, I moved two desks, placing them side by side, and then stretched my bedding out over them, first of all shaking the sheet out to remove newcomers. I then doused the table legs with great amounts of insect powder, and stretched out on my improvised and uncomfortable bed, confident that I had placed a cordon sanitaire between the enemy and me. Whether they broke through this barrier or dropped down from the ceiling, I know not. All I know is that I was obliged to give up and accept defeat. The only alternative was to get dressed and go outside.

The mornings were pleasant until ten o’clock, although it was mid-August. Having visited the Serbs the day before, I resolved to pay a visit to the Albanians.

Peja is the great Albanian town of the north, and was even more so under the old regime. It is located at the foot of the mountains belonging to the wildest and most independent of the tribes and is far from all natural roads of communication. It is separated from Mitrovica by a long day’s journey through empty land and scrub, in which many surprises are lurking. But as a rich population centre, it is the home of the wealthiest beys of the north. It is here, and was here, that about thirty noble families reside – families of the hereditary chiefs of the greatest tribes of the interior. Side by side are those who have made their fortune and others, wretched peasants and poor beys, who live in lowly farm huts. The man who was considered the wealthiest among them was the oldest of them. He was called Yashar Pasha, and the Young Turks made him a member of parliament. It was commonly said in Peja that he was the only Albanian there who was favourable to the constitution, i.e. the new regime. I had no difficulty believing this, especially for the rich Albanians. The hereditary beys had enjoyed uncontested rule throughout the country. The governor was simply a tool in their hands and if he put up any resistance, he was dismissed immediately by means of a cable to Constantinople in which the sultan was informed of the wish of his faithful Albanian subjects for him to be relieved of his post. It was under such circumstances, I was told, that the Albanians, or rather one of their beys, expelled Javid Pasha who, taken unawares, was thrown out of his bed and summarily escorted to the edge of town. If this story is true, Javid Pasha succeeded in taking his revenge. However this may be, a conflict was raging on the eve of the Serbian conquest, between the Young Turks who wanted to rule the country under their mutasarrif and the beys who wanted to maintain their authority. The governor won the first match and the beys were forced to bow their heads. The population of Peja and the surroundings was partially disarmed and brought under control, but they were not forced into total submission. Although the town was held in check for some time by an energetic governor supported by his faithful troops, when an opportunity arose, the countryside rose in revolt once again, and finally, in August 1912, the Albanians, led by their beys, read out the law to the Sublime Porte.

The current peaceful phase is only a façade, behind which tension still bubbles. The Young Turks managed to appoint their member of parliament, Yashar Pasha, who was favourable to the new regime. He was a man they could manipulate. He was given a fortune of a million Napoleons, earned in part, as it was said, in public tenders and they were easily able to impose his candidacy. But the sentiments of the Albanians did not change for all.

The most famous family in Peja was that of Mahmud Begović. It was an old and very wealthy clan. It was said that he owned land and assets amounting to perhaps 500,000 Napoleons. The current head of the family was Zenel Bey who resided in Peja itself. He was the real chief of the family. His relations with Haki Bey were cool, however, he had not broken with him and recently visited him. I went to see him in his fortified manor in town and was led to the selamlik on the upper floor. The two or three windows, usually hermetically sealed, were opened and I was given a seat on the traditional divan that stretched all around the room, surrounding the fireplace. As is custom, there was no other furniture in the room. My visit caused great commotion, disrupting habits and perhaps surprising people. A young man from the family or a servant brought me some ice water perfumed with violet and amber, and some jam. In line with tradition, I took a spoonful of it, quite delicious as it turned out, and drank one of the glasses of water. A moment thereafter, another servant brought me coffee and cigarettes. Zenel Bey, a man of over fifty with almost white hair, then came in. His gait was youthful, his body tall and slender, his eyes bright and shining, and his allure and manner of conversation revealed him to be a leader able to act and to be prudent. That day, he was in a prudent mood and I was not able to get much out of him. However, when I asked him about a possible cleft between rich Albanians and poor Albanians, he replied more or less as follows: “In the old days, people did not pay tithes. Now they want to impose them upon us. They are already being collected in Peja and the surrounding regions, although not everyone in the country has submitted to them. We did not used to do military service. Now they want the tribes to provide recruits or pay fifty pounds. Faced with these new problems, all the Albanians have the same interests.”

In the courtyard, as I left the house, I noticed a little boy of seven or eight. He had a keen glance and lively movements as he waited for me to pass so that he could get a good look at me. Behind him were the heads of other men in the half-opened doorway who hardly dared to show themselves.

I asked him who he was and who his friend was. He replied confidently that he was the son of Zenel Bey and that his friend was a relative. He was wearing a costume that was quite different from that of the average Albanian. Instead of the narrow white trousers with thick black braiding extending down around the ankles and forming the soles, he had baggy brown trousers with broad light-blue stripes. Over this wide cloth sash that held up his trousers and concealed a row of cartridges, he wore a sort of striped waistcoat with gold embroidery on the inside, under which one could see a flannel shirt. On his head he wore a white skullcap, his hair having been parted recently by his mother. This costume, quite becoming, was completed by a ribbon he had around his neck that held some amulets. The men usually replace the cloth waistcoat with a gold embroidered bolero or a simple cloth over their white shirts. But the little white skullcap is de rigueur and is the national headpiece of the Albanians. Sometimes it is widened out and takes a semicircular form instead of a cone, though this is rare. However, when I was walking through the market of Peja shortly thereafter, I saw several people, children in particular, wearing their headpieces in this fashion. For Western eyes it is a curious sight, but one soon gets used to it. Indeed one soon begins to prefer it to the red fez.

When I left Zenel Bey’s, I paid a visit to another leading Albanian. There were three or four rich merchants. Elias Aga, Gjelo Effendi and Zhivko Effendi, who were neither pashas nor beys, who had made their fortunes in various commerce. The foremost among them was Elias Aga who, instead of being a simple ‘effendi’ which is a ‘mister,’ was an ‘aga’ which is a landowner. The title is difficult to translate, being somewhere between ‘mister’ and ‘lord.’ He had made his fortune on flour. It was he who milled all the country’s grain (of which there was not very much) and maize in the mechanical mills. He was away from his home and far from Peja at that moment I came by. But, flattered by the visit of a foreigner, his son came around to see me right away and, as a present, he brought me a handkerchief of threaded silk. He paid me a thousand compliments and gave me his best wishes, noting that he, his father and his whole family were very moved by the honour I had done them. He wanted me to return that evening and have dinner with them, but I had already made arrangements to visit the monastery of Deçan [Detchani] and had to decline his invitation. He then departed, heaping me with greetings and best wishes, and in was under such auspices, more favourable than those of my arrival, that I left the mysterious town of Peja.

From Peja to Prizren

One can easily reach the monastery of Deçan by carriage in three and a half hours along the route that bears the same name. It runs along the foot of the mountains through countryside that is less barren than that between Mitrovica and Peja. About two thirds of it was farmland and they rest consisted of scrub. We passed through two or three important villages, among which were Lybeniq [Lubenitz] and Strellc [Strtlza], called Strelci on the Austrian map. In the former, we were surprised to come across an assembly of some twenty Albanians sitting in a circle on the ground in the village square. They had come from all around and I had no doubt that they were discussing what attitude to adopt towards the authorities following the harvest period. There was total silence as we passed. Who knows? Perhaps some Albanian hodja would wield influence upon the assembly as a result of the passage of a European dressed in western clothes. At Strellc we stopped for a rest under some majestic trees, in the shade of which was an icy spring. Some Albanian peasants in white cloth costumes with dark-coloured boleros talked and stared. The village was fortified and each of the houses we could see was a little fortress of its own. They were all ‘towers’ or kullas of characteristic architecture. The walls were so thick and the loopholes so tiny that no bullet could get through them. Mortar fire would be needed to destroy them.

"The monastery of Deçan [Visoki Dečani]" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).We followed a bumpy trail up the Deçan River and finally caught a glimpse of the monastery at dusk. Instead of continuing in a straight line, the mountains here curve around, as if to facilitate the passage of the little river that emerges out of them. Between the wooded slopes there was a plain about one kilometre long surrounded by the semi-circle of mountains and opening out onto the plain of Gjakova. It is said that this is the oldest of the Serbian monasteries, and it is one of the richest. A double set of walls and a moat defend it against attack. One can only enter or leave by means of a drawbridge. Protected by a little fort, this monastery is a veritable Serbian bulwark on Albanian soil. Within the compound there are large buildings that serve as lodgings for the monks, for their guests, for their numerous servants, and for the farmers and shepherds who make up the Serbian colony. The monastery possesses much land. Everyone is involved in agriculture and they all return to the compound in the evening. In times of crisis, they go armed and within the walls they can repulse any attack. At the time of my visit, they even had a detachment of regular soldiers and an officer, given to them by Haki Bey to ensure peace in this region.

Haki Bey had announced my arrival by cable and on the drawbridge waiting for me for several hours were the archimandrite, the officer, several monks and a mass of servants. The archimandrite was an easy-going old fellow with a burgeoning red nose and a long white beard flowing down his old black cassock that itself looked something like a bathrobe. As it was late, we hastened to visit the chapel. This was a Romanesque building of two-coloured stone, upon which rested a Byzantine dome that was being repaired. Indeed all the church walls were being resurfaced.

The monastery was extensive in size and was able to host large numbers of guests. I was given a nice room with a clean bed, a table, chairs and a dressing table – a luxury in this country. We dined simply, but well. The monastery seemed to be well off. I was told that it was supported by Russian money. At any rate, I noticed engravings of the Tsar and the Tsarina and former tsars on the walls. We spent quite a bit of time in the little dining-room drinking and talking. The monks had me try their excellent liqueurs that they distilled themselves, and the wine they made. They had a beautiful vineyard that produced a red wine that was lighter in colour and contained more alcohol, but was tasty. There were fruits and vegetables in great abundance. It was a land of milk and honey, or would have been, had they been able to live in peace.

It was six hours by carriage between the monastery of Deçan and Gjakova. The first part of the journey took us across a dusty plain of scrub on which we met but one Albanian on horseback, followed by his wife on foot. I photographed them very cautiously because the Albanian might have regarded this as an insult to his honour, since his wife was with him.

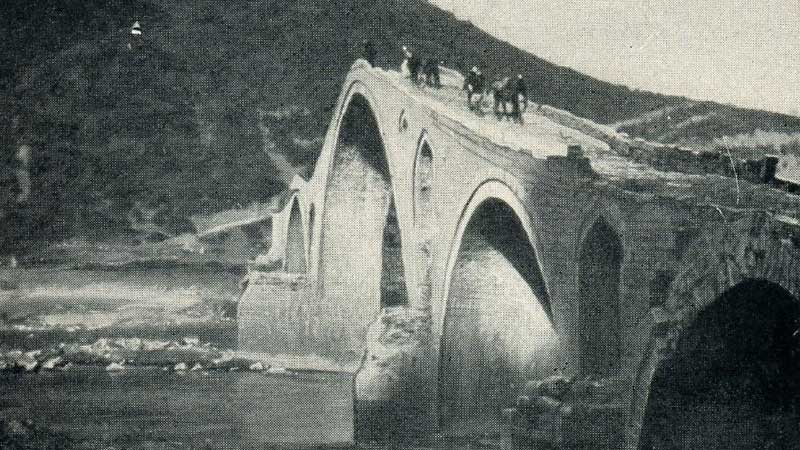

"Gjakova: bridge over the Krena River" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).

Soon there were trees and we passed through the village of Skivjan [Skivien] where the minaret of a mosque surrounded by tombs rose amongst the poplars. At a bend in the road we could then see the first houses of Gjakova in the distance. No fortification indicated the limits of the town which seemed extensive in scope. We could then see the first walls of the bazaar and river that constituted the real centre of town. The Prna River, called the Krena on the Austrian maps, that flows through Gjakova, was almost dry at that time of year, but in the springtime it was a torrent that ate away at the steep banks and filled its deep bed. An old stone bridge in Romanesque style had been built over the river hundreds of years ago. It was wide and quite long, but without railings. It had low arches and resembled the back of a donkey, and gave the town a curious look. It was commanded, if you will, by a tall and mighty-looking kulla with loopholes facing the bridge. Its sidewalls were in a state of collapse. In the distance were the bazaar and the grand mosque.

The offices of the kaimakam were not far away from the bridge – wretched offices and a wretched official, I must say. He seemed to be a functionary of the old regime who had been left in power by the new one. He was ignorant and lazy and left all official business to his secretary, a young Albanian who, curiously enough, knew how to write Turkish well, but could not speak it. The secretary offered us cigarettes and slices of watermelon which were particularly refreshing in view of the brazing heat outside. We spent some time resting and savouring the juicy slices.

The kaimakam’s secretary offered to take us through the town which seemed almost empty. In the bazaar there were only a few children around, who came up to have a look at us. At the back of the dark shops, we could distinguish Albanian figures, lying or seated, who were smoking or sleeping and waiting for the heat to pass.

One curious thing did happened during our walk. All the way to the bazaar, the kaimakam’s secretary strolled to my left and conversed with my dragoman in Slavic because he did not know Turkish. We did not meet anyone. Just before we got to the bazaar, however, he excused himself, saying that he had to leave us but would join us at the other end of the bazaar. As I expressed some surprise, he explained that he was fearful of incurring the wrath of some of his fanatic compatriots if he turned up in the bazaar in the company of Europeans who, themselves, were accompanied by Turkish gendarmes. The action undertaken by the Young Turkish regime in Peja under Javid Pasha and Ismail Haki Bey had obviously not been felt to the same degree in Gjakova.

As we passed through a narrow alleyway, the secretary showed me the Albanian Catholic parish. I asked if the priest were at home. A wizened old woman who served as his servant replied that he was sleeping, but that we should enter anyway as he would be delighted to see me. I thus went in with the secretary, my dragoman and three of my soldiers who would not leave my side. The parish priest, who had been shaken out of his sleep and whose eyes were still puffy, soon came down. Despite the Serbian ending on his name, Glasnović, he was an Albanian and served a large parish together with his vicar. It comprised Gjakova and all its surroundings. The vicar was an active, intelligent and quite well educated young man and we conversed for some time before lunch, since the kind priest insisted that I share a plate of eggs and spiced vegetables, coffee and local alcohol with him.

The Albanian Catholic parish of Gjakova is dependent upon the Archbishop of Skopje [Uskub]. The Archbishop himself now resides in Prizren. The parish apparently counts 1,200 Catholics from fifteen households in town and 300 elsewhere.

The Albanians have three Catholic hierarchies. The first are the monasteries that belong to the Franciscans and that are subsidized by the Austrians. In Peja, for example, there is a little Franciscan monastery which is under the Austrian protectorate. The second are the parishes under episcopal hierarchy. The Albanian metropolitan resides in Shkodra [Scutari of Albania]. The two archbishops have their sees in Durrës [Durazzo] and Skopje respectively, although the latter in fact resides in Prizren. Finally, there are the three bishops in Pult [Pulatti], Lezha [Alessio] with its see in Kallmet [Kalmeti], and Nënshat [Nenshati] which is the see of Sapa or Shkodra. Austria claims the right to protect these bishops and their subordinate parishes, but the simple priests tell it differently. They will say to you, “We are neither Austrians nor Italians, we are simply Albanians.” Some of them do, indeed, receive support from Austria or Italy, and sometimes from both at the same time. On occasion, only their superiors, who receive regular subsidies from Austria, know where the funding comes from.

The third Albanian Catholic institutions is the most important and the best known. It is that of Mirdita, the large Albanian tribe whose territory extends southwards from Shkodra and is entirely Catholic. It is estimated that it comprises some ten thousand armed men. It alone comprises more Catholics than all the other Albanian regions together. It is divided into sixteen parishes under the authority of the mitred Abbot of Orosh whom I was later to visit in Shkodra and who received me in Orosh. He was formerly dependent upon the Albanian metropolitan of Shkodra but in 1888, when he got back from exile, the abbot had Rome give him autonomous jurisdiction and he is no longer a suffragan of Shkodra. He depends directly on the Vatican and hold the rank of an archbishop.

The Catholics of Gjakova got on quite well with the Young Turkish authorities. They were ready, said the parish priest, to pay tithes and do military service, even in peacetime. The secretary replied to this, saying, “You are then Young Turks yourselves.” “Indeed,” said the priest, “and there are not many.” Relations with the Muslim Albanians were excellent, although this had not always been the case, in particular at the end of the regime of Abdul Hamid. They attributed this to actions undertaken by Austria and Italy in their country. As to relations with the Serbs, there was nothing to be said. Of the 3,000 houses in the town of Gjakova, there were only about twelve homes of poor Serbs and there were none in the surroundings.

This region is thus purely Albanian and, like Peja, it is dominated by a small number of families of rich and powerful beys. The oldest family is that of Riza Bey who was exiled by the old regime for personal reasons. The new regime astutely called him back and made his son, who was an officer, a member of parliament for Gjakova. There is another bey who is an officer in Skopje, He is called Bayram Tzura [Bayram Curri]. The others live in Gjakova. Among them are Ahmed Bey and Jelaledin Bey who is possibly the richest of them, with land worth a million and a half piasters. All of them made their fortunes in farming and none of them in milling or manufacturing as in Peja or Mitrovica. This shows that we are in a country of great landowners. […]

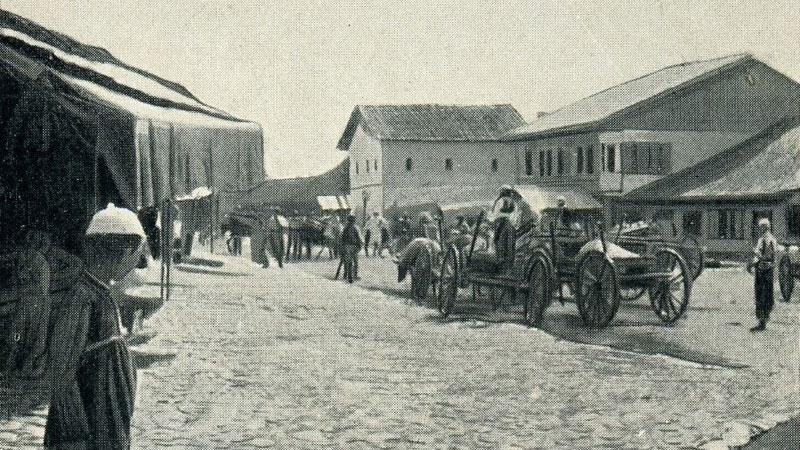

"From Gjakova to Prizren: bridge of the Erenik River" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).

I left Gjakova at three o’clock in the afternoon, with my carriage advancing over the dusty plain that stretched to the Evenik (or Erenik) Bridge which we crossed. The bridge is about one kilometre long and difficult to pass. The stones are so badly hewn that one is forced to walk on the sharp ends. My soldiers preferred to ford the river, but cautiously because in the distance we heard shots and saw a group of Albanians sitting with their horses in the shade and seeming to gather together. I had the rifles loaded, but this was unnecessary for we continued our journey unimpeded.

My driver made a mistake in his planning. Six hours of forced march are needed to get to Prizren and it was already dark by the time we arrived. It was market day and I spent the last two hours of my journey passing at least three to four hundred peasants, almost all of them Albanians, men and a lot of children, many of them being armed. The disarmament of the country is far from complete, even on the plain, as I was told. There were rifles over their shoulders, cartridge belts around their waists, and pistols and daggers in the wide sashes wrapped around their bellies and thighs. Most of them were on foot and they walked lithely and rapidly. Some vehicles followed, loaded with goods of all kinds. Everyone stared at me with great curiosity. Yet there have long been foreigners in Prizren, even two permanent consulates. It was in the dark of night that my carriage stopped in front of the Russian consulate, thus bringing an end to the first part of my journey.

Prizren

After Skopje, Prizren is the largest city in the Vilayet of Kosovo. One has to climb up to the citadel with its dilapidated walls and mangled battlements that crowns the town in order to get a view of the houses packed together at the foot of the mountain, of the alleyways that are so narrow one has the impression that the walls on either side of them touch one another, of the ponderous mosques crowned by domes of white stone shining in the sunlight, of the slender silhouettes of minarets that punctuate the town like bright needles, of the cypress trees between the houses that add a sombre note, and of the poor cottages built on the hillside, clutching as best they can to the rocky and moving soil. As elsewhere, there are barracks in this citadel, too, keeping the town under the watch of their rifles ever ready to fire. The panorama opens up gradually along the uneven path that leads up to it. The town seems to be in the protective custody of the mountain into which it snuggles.

"Prizren: the police station in the market" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).

Albanian towns usually have a fondness for greenery and water, but the waters of the Bistrica River descend from the mountain gorges at such a speed that they hurtle through the town rather than meander and rush off towards the plain to hurl themselves suddenly into the Drin that absorbs them. There is no room for greenery here. It is restricted to the suburbs on the plain. Prizren is a great hub of commerce between the plain of Skopje and that of Gjakova on the one hand, and between the flat land and the mountains tribes of northern Albania on the other. It is an important market and, at the same time, a seat of some very prosperous small manufacturing businesses. The market and the bazaar are the true heart of the town. The centre is dominated by a major police station that struggles to keep order and settle disputes between the people of the interior of the country and those of the town and plains. Three or four streets are lined with shops offering a wide range of handicrafts. One finds filigree silverwork and objects of gold inlay. Skins and hides are tanned here, and cloth and silken textiles are woven. They also produce knifes and daggers. Thousands of small handicraftsmen keep this industrious and commerce-minded population busy.

The Russian consulate very kindly not only offered me its hospitality but assisted me actively in preparing for my coming journey through the interior. This was not an easy task. It was more or less impossible to get exact information even on the routes to take for the first two days, not to speak of greater distances. Down to Kukës [Kukus] that some call Kuks and most people call Kuksa, one follows the course of the Drin River and I was given the approximate time needed – seven to eight hours on horseback. But beyond that, the route was unknown. The Russian consul summoned his kavasses and asked them to gather information, but what they brought back was very vague. As such, we all decided to pay a visit to the Austro-Hungarian consul, a short, blond young man who was reputed to know the country because he had been shot at by the men of Kukës where I was headed. Without alluding to that unfortunate incident, I asked him if he knew the road, of any places where one could possibly spend the night, and of any difficulties. He knew nothing, but called in one of his Albanian kavasses who had been to Bisak [Bissac] where he had friends. Unfortunately, he could only give us some very general information about the route. We then visited the mutasarrif, Fuzi Bey, to organise the journey definitively. He was very kind and asked his officers to find some policemen who knew the region. But among the Turkish and Albanian policemen present, there were none who had been that far. The interior was unknown between Kukës on the Drin and Orosh.

"From Kukës to Orosh: the famous Viziers' Bridge over the Drin River" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).

We decided on the following plan. The mutasarrif would give me an official escort of soldiers and police on foot. At the Luma Bridge, just before entering Kukës, I would stop and send the Albanian policeman on who was related to someone in that settlement, giving him a message, and he would negotiate my passage with the Bey of Kukës. With the agreement of the latter, I would then recruit an escort of men from the tribe and I would cross Luma territory with these two escorts. At the same time, the mutasarrif would telegraph the vali or governor general of Shkodra to inform him that I had left Prizren and to send me an officer and some men to Orosh.

Then there was the issue of ‘hats.’ On the day of my departure, the French consul in Skopje sent me an urgent message from the governor general of the vilayet, stating, “I met the vali last night. He has asked you to do him the favour of wearing a red cap or fez during your journey from Mitrovica to Shkodra. He is convinced that incidents could be avoided this way. Your dragoman should, accordingly, also adopt this headdress. I would ask you to follow the request made by our governor general.” At that moment, I decided to acquiesce to his wish although I had my misgivings. However, at Mitrovica, Javid Pasha had persuaded me differently. I thus asked the mutasarrif of Prizren and the consul. In the end, I decided the keep my European headdress and believed this was the most prudent thing to do. As I was being escorted by police, and with my clothes, my behaviour and my inability to speak a word of Albanian, I would not have been able to deceive even a child. By wearing a fez, I would be trying to make everyone think that I was a Turk or a Christian in disguise. Neither were so well looked upon that I should try to copy them. On the other hand, there was the possibility that some fanatic might be horrified at seeing someone in a hat instead of a fez, but for such a case I had my escorts to protect me. In the final analysis, I felt it was safer to travel brazenly and to declare my nationality openly, and then ask for safe passage and support.

The last issue to be solved was that of transport. It goes without saying that no carriage, not even the smallest, could get through the interior. The trails consisted of narrow paths along which travellers were often forced to clamber like mountain goats up rock faces, avoiding falling rocks on their way. We had no choice but horses for the six or seven-day journey. The direct trail from Prizren to Shkodra, along the Drin, takes two to three days, but my roundabout route involved a large detour southwards. The kavass and the dragoman gave me their opinions and we set off for the horse-and-wagon market. Finally, we found a man who agreed to accompany me and to loan me three horses for six Turkish pounds. One of the horses was to be saddled in European fashion with a Spanish saddle that I was shown. This was important because the saddles in this country are pure torture. They are better for carrying baggage than for men. […]

The Drin Valley and Luma Country

Prizren is the last stage before the mountains begin. It is from there that one departs to enter the long corridor down the Drin River that leads to Shkodra. This trail was once much used and, before the construction of the railways in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, exchanges between East and West took place along this route. But few traces of it remain. The trade routes have moved elsewhere. The isolation of Albania and the spirit of independence and rivalry among its people have done the rest. What remains is a poor and dangerous trail that is only used by the people of the interior.

By six in the morning, my escort, my guide and his horses, my dragoman and the kavass of the Russian consulate were all on their feet. The baggage and provisions for several days were loaded onto the horses and our little caravan set out from Prizren for the plain over which we were to reach the Drin in two hours. According to what I was told, the first stage of our journey would last six hours and would take us to Kukës.

The road, suitable for vehicles, stretched through the cornfields and crossed a tributary of the Drin. Soon, fields of scattered rocks replaced the corn, and the route curved to reach the Drin, across from the little Albanian village of Shalqin situated on the other bank just above the river. From the distance it looked pretty wretched. The few houses in the village were dominated by the kulla of a bey that was now in ruins. We reached the Drin at the spot where it enters the valley. The latter was initially broad and open, but then gradually narrowed to a gorge. The river flowed in a rather deep bed and looked rapid. On the left bank, it was fed by a number of small creeks that we passed over, hardly noticing them. The road ceased here to be suitable for vehicles and turned into a mule track along the riverside but presented no difficulty. The vegetation became more and more sparse, especially on the southern bank that we were following. It was a rather sad looking landscape of bushes and gravel. However, numerous springs gushed near the trail and flowed right into the Drin. From time to time, an isolated tree provided a bit of shade. For the last hour, my horsemen, who had not had anything to eat, endeavoured to overcome their hunger by singing. Their songs had a lugubrious rhythm to them, slow and sad like a dies irae. Our small horses, the size of donkeys, were as sure-footed as mules. They plodded through the gravel that split under their feet. We saw no houses marked on the map and there was nothing left of the old han but a hut of leaves. It would hardly have served as a shelter in a rainstorm.

To the great joy of the horsemen, at about eleven o’clock, we finally caught a glimpse of the badly boarded walls of the han (called Novi Han on the Austrian map) and the courtyard fenced in by pickets and branches. An elder Albanian offered us a jug of fresh water, a bit of hay and a litter, and the hut to shelter the men and animals. My gendarmes took immediate advantage of the stop to take a long nap. This, they insisted, was a tradition respected by all travellers. But it was yet early. The sun looked like it would be scorching by one o’clock, and I was not too convinced about the information I had been given. As such, I only gave them half an hour to rest, and lay down myself in the shade of a tree where I took part in the frugal meal of my escort. From the bags hanging at the back of their wooden saddles, the horsemen drew out bread and cheese that was made of curdled milk and quite hard. They ate this with various peppers that they always had with them. After this, they munched on cucumbers. At this point, the Albanian from the han went off to fetch some fresh water from the spring and the jug was passed from mouth to mouth. Lunch was over and we got back into our saddles. Despite the breeze in the valley that made the temperature more bearable, it was already so hot out that everyone wanted to have one last drink for the road. Fresh water was passed around in the same jug until it was empty again. The Albanian was quite satisfied by the half a piaster we gave him, and wished us a pleasant journey.

Somewhat less than two hours later, we reached the Luma River that was spanned by an old stone bridge without parapets. It was formed by one distinct arch, and the climb up it was quite steep. The stones in the bridge were uneven and there were so many gaps between them that everyone got off his horse to lead it by the bridle. Once we crossed the bridge, we stopped to rest in the shade of the large trees, and I had something to eat with my dragoman.

The trail up to this bridge which took us six hours to reach – six hours on horseback – was quite good and it would be no great problem to build a road or a railway along it, if this route should be chosen for the so-called Danube-Adriatic rail line, but there are no services along the route. Before the trail enters the gorge, there are two or three villages with a few houses, but for the final three hours, it is a desert, a sea of rocks with meager vegetation consisting mostly of bushes. The Drin which, at the entrance to the valley, flows rapidly and with several metres of water in its narrow bed, is almost dry at several points where the bed is wide and where the water meanders through the rocks. When the water level is low, it is no difficulty to follow the path along the river. Apparently, when the river is high, the path is sometimes cut off by flooding. One then has to take a trail over the mountains that ends at the same spot, the Luma Bridge.

While we were resting, I sent one of my horsemen who was related to the Albanian chieftain to ask him for hospitality. He was to explain my intentions and ask him to allow me to visit his home.

The village of Kukës is situated half an hour from the bridge. About an hour later, my horseman returned accompanied by the brother of Sul Elez Bey – for this was the name of the chief of that village – as well as by two men from the tribe. They arrived at the border of their tribal territory to welcome me and convey the greetings of their chief and let me know that he had accorded me hospitality. We set off immediately in Indian file along the narrow path through the bushes that led from the Luma Bridge to the village of Kukës.

Kukës is wonderfully situated on a small plateau about a hundred metres above the Drin River. It looks like an island or a fortress, with the Drin to the north serving as its moats. To the west and south is the Black Drin that emerges out of the mountains here and flows into the White Drin not far away. Just below Kukës, it forms a large curve, the inner side of which contains a dried-up lake with ponds here and there reflecting in the sunshine. To the east, the Luma River, whence we arrived, encloses the fourth side. This little plateau dominates the three valleys, those of the Drin to the east and the west, and that of the Black Drin to the south, the waters of which subside and dissipate at Kukës. There are three high mountains in the background. To the north are the mountains of Has, the distant peaks of which form a continuous line. To the southwest is the Maja e Runës [Maja Runs] and the neighbouring lower hills that separate Mirdita country from Luma. To the southeast, finally, is the cone-shaped Gjalica [Djalic], which raises its rocky head to an elevation of over 2,500 metres and dominates the whole region. It is the heart of Luma territory.

"Kukës: the tribe of Sul Elez Bey" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).

Sul Elez Bey and his men were waiting for me outside the entrance to his kulla, around which about a dozen wretched huts had been built that made up the whole village. From the information I was given and from what I was able to confirm here, I understood that the bey was only the head of a village, a peasant among peasants. He was both the chief and equal to the rest. He was not the sort of landowning bey who owned a whole village and populated it with his tenant farmers. Each family had its own hut, its own flocks and its own land. But Sul Elez Bey was the head of an old family that traditionally commanded this tribe. He was wealthy in property, he had a large family and extended relatives, and his influence was widely acknowledged. As the bey of Kukës, a site that is strategically located at the confluence of the rivers and at the junction of trails constituting the most important routes of communication in the region, Sul Elez Bey played an important role in the country and his support was nothing to be sniffed at.

There he stood, a bit in front of a dozen fine men, the oldest of whom were just as upright and sturdy as the younger ones. The clothes that many of them were wearing were different from those of the Albanians in the lowland towns. Their white flannel or woollen trousers with black trim were baggy and were closed at the ankles with gaiters. Their woollen shirts were replaced by a wide cloth garment that fell to their knees. Over it, all of them were wearing a vest or bolero of more or less coarse cloth but also more or less embroidered. The vest of the chief was luxurious compared to the rest, and he had a silver chain around his neck. The white skullcap, as round as that of an altar boy or flat like a travelling bonnet, was standard apparel for all, as were the rawhide sandals and the wide sashes in which each of them had stuffed cartridges, weapons, tobacco, watches and such provisions. A further complement to this costume were the rifles over their shoulders. You can imagine the impression they made on me when I first caught sight of them.

Once we exchanged greetings, Sul Elez Bey invited me into his house. The moment I entered, I was, as it were, under the protection of his sacred besa. I was his guest and was thus inviolable. All the men of the tribe were now obliged to be hospitable to me and to defend me with their weapons. I entered the kulla. It was a square building with four thick stone walls and deep foundations anchored in the soil. The main floor was a simple room to store wood and tools and did not have a direct connection with the upper floor. The latter was reached by a wooden staircase, rather more like a ladder placed against the outer wall of a building that could be removed in an instant. The upper floor consisted of one large room divided into two parts: one side was for the provisions and the other side was for guests. This is where one spent the night. As to furnishings, there were only carpets laid out on both sides of the high wood fireplace. Air and light penetrated the room by means of the low-placed doorway on which the staircase was leaning, and by two windows which were rather more like slits in the wall, high above the ground. Between the carpets was brick flooring right to the hearth. The embers were at once stirred up and coffee was made. When I entered, I removed my boots, as is custom here. No one enters the living room with his shoes on as the carpets in an Albanian home also serve as beds and chairs. Everyone thus takes them off and places them carefully in a corner of the room, together with his weapons, and then takes his seat on the carpet. The cafedji [coffee maker], a servant especially for this job, prepared the coffee and offered me a cup. In the meanwhile, someone went out to pick some pears and I was given several of them. They were small, but ripe and juicy.

My hosts sat cross-legged. This position exhausted me, especially after a seven-hour horse ride, so I stretched out with the saddlebags behind me to support my back, and the conversation began. With the help of my dragoman, I explained to them where I had come from and where I was going, what my plans were and what I wanted to ask of them. I wanted to cross Luma territory to get to Mirdita to the south. No European had yet taken this trail and I was curious to see it. They deliberated among themselves for quite some time. The bey, his brother and the eldest man of the tribe who seemed to constitute a village council discussed what trail ought to be taken. The Luma tribe had bad relations with the neighbouring tribes, and it was important to avoid their lands and to get to Mirdita via friendly territory. With Sul Elez’s recommendation, the Mirdita would give me their besa. The discussion continued for some time. I noticed that they were a bit uneasy. Finally, the bey told me that I was to take the mountain trail which was safer at the moment than the track up the valley. He would give me an escort of men from his tribe who would accompany me to the border of their land and would hand me over to a friendly tribe to whom their tribe had earlier provided assistance.

"Kukës: the men sent by Sul Elez Bey" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).

I then asked them about the situation in Albania. The bey had just received news from Prizren that the mutasarrif was demanding the payment of tithes. I asked what he intended to do, and he replied: “We have never paid them, why should we start now? They give us nothing and we ask for nothing. There is nothing and no one we need from them. So why do they make such demands of us?” Indeed I could think of no service that the State had ever rendered to them.

The central government has not existed for them for decades, probably for centuries. They do not recognise the Turkish Government, only the religious authority of the sultan in matters of faith. Aside from this, these tribes are entirely independent. They are traditionally grouped into confederations. Luma, Mirdita, Hasi and Malësia, etc. are the names given to them. But in the northern mountains, these confederations do not recognise any sovereign authority. They are an agglomeration of tribes, whose territories have long been marked out, and each of them governs itself freely. In case of grave danger, the chiefs of the tribes gather and take decisions jointly. These are usually experienced warriors who rise either against the Turkish authorities, against the Christians, upon an appeal from the sultan for holy war, or against other tribes. In their relations, however, they observe one common law. This is a sort of traditional code like the law of the Salian Franks or that of the Visigoths in ancient Gaul. It is called the law of Dukagjin. Conflicts arise between the tribes for many reasons and result in blood feuds. Blood can only be requited by blood. It is thus always uncertain as to whether one can travel from one tribe to the next. One day they are friends and the next day they are enemies. As such, they have only intermittent and varying relations. During my visit, the Kukës clan had good relations with the neighbouring tribes of the Mirdita confederation, but claimed that it had good reason to complain about the other clans of Luma, of which it was part. […]

This region is very poor in arable land and hardly able to sustain its inhabitants. The people thus feel the need to emigrate, temporarily or permanently, to make a living, or sometimes only to purchase the fine arms of which they are extremely proud. An abundance of gunpowder, cartridges, modern rifles and pistols hang around the pommels of their horses. They are well informed about most modern weapons and, while they may not all have them, some do and others want them. The oldest among them asked my dragoman: “Does the Frank have rifles?” On hearing our reply in the negative, he added: “Well, tell him when he goes back to his country that he would make us very happy if he sent us a Mannlicher. That would be the finest present he could give us.”

[Excerpt from Gabriel Louis-Jaray, L’Albanie inconnue, Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1913, pp. 38-80, 87-98, 100-101. Translated from the French by Robert Elsie.]

TOP

!["The monastery of Deçan [Visoki Dečani]" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909). "The monastery of Deçan [Visoki Dečani]" (Photo: Gabriel Louis-Jaray, 1909).](GLJ066A.jpg)