| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

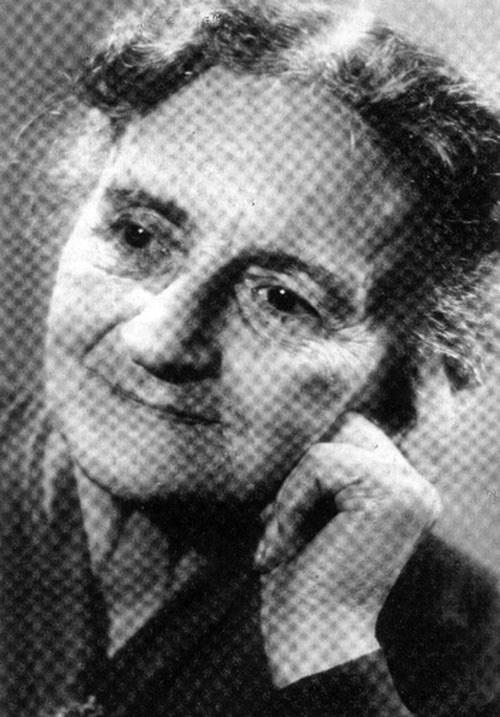

Baroness Marie Amelie von Godin

(1882-1956).

1912

Maria Amelie, Baroness von Godin:

The Declaration

of Albanian IndependenceThe German baroness, Marie Amelie von Godin (1882-1956), was born and raised in Munich in the traditions of the Catholic Church as the daughter of a family of Bavarian aristocrats. In 1905-1906, she travelled with her younger brother to Athens, Constantinople and Palestine. It was on board a vessel bound for Constantinople that she first met an Albanian, Avdi bey Delvina, who invited her to visit his country. In 1908, she finally got to Albania where she met Ekrem bey Vlora of whom she was to be a close lifelong friend. It was no doubt he who inspired her to devote her life to Albania. Baroness Godin travelled to visit him in 1910 and once again from September 1912 to April 1913 when she was caught up in the chaos of the Balkan War and personally witnessed the declaration of Albanian independence in Vlora, on which she reports here.

Syreja bey Vlora (1860-1940).

It was the educated class of Albanian society that the Vlora family, that is to say Syreja Bey and Ekrem Bey, could best rely upon from the start. For most of these men, a simple word was enough to convince them to take part in the planning for a joint assembly, in particular because they had all been politically active in the past few years and recognized the significance of the moment, and because most of them were simply waiting for someone to make the first move.

Since they were related to the last four powerful feudal families in the country - the Vloras, the Toptanis, the Libohovas and the Delvinas - they had influence in their respective towns and could convince these towns and the surrounding regions to take part in the planned league. However, it was not enough to win these towns over because, if the league were to be of any real significance, it would have to include representatives from all the larger towns in Albania, and would have to comprise the middle class and the population in general. Only then would the venture be without peril for its initiators. Turkey had not yet been defeated and its troops were positioned all around the Albanian border. It was still in a position to outlaw and hang the leaders of any political movement it did not approve of. Yet events of the past few years had shown that popular movements in Albania usually ended with an amnesty for their participants. It was important to win over the middle class and the population at large. In view of the bitter conflicts between the political parties and the very diversity of the Albanian population - a people unschooled in politics - and the lack of experience of many of its leaders, everyone understood that it would be extremely difficult to win the population over for any joint undertaking within a period of three weeks.

These difficulties would have been enough to stymie any other Albanian leader, but for Syreja Bey and Ekrem Bey there were additional problems to be overcome that were related to them as individuals. Neither Syreja Bey nor Ekrem Bey lacked exceptional talent and there was no one in Albania who would have denied that Ekrem Bey had worked unceasingly for Albania since his early youth, in particular for Albania’s inclusion in the Austrian fold. But neither father nor son had spent much of the last fourteen years in Vlora and, as a result, they had lost contact and direct relations with people of influence there. In particular, when Syreja Bey was given permission to stand at the elections as an opponent of his cousin Ismail Kemal Bey Vlora, the whole family, town and surrounding region was bitterly divided into two opposing camps. When Syreja Bey ran as a candidate for the government last year and won the race with government help (the means used by the Young Turk Government to impose the candidates of its choice are now well known), he was faced with the fury of the other side. This hostility was unjust because Syreja Bey was not responsible for the electoral manoeuvring that took place at the national level, and no one in the Turkish Parliament represented Albania’s interests better and more honestly than he did. Nonetheless, the hostility was there. Another problem that the Vlora family was faced with, was the particular mentality of the people of Vlora. As inhabitants of a port city with much incoming influence, a city in which it was not difficult to make a living, in particular for those who were ready to leave the main track, so to speak, many of them, more so than in any other town in the country, evolved into the most devious tricksters, intriguers and parasites that one could imagine, individuals that I would call the dregs of Albanian society. Men who have no clue as to what selfless behaviour is, can hardly be expected to appreciate it in others. For this reason, many of the people of the town of Vlora were convinced that Vlora senior and Vlora junior only had their own interests at stake with this plan. One good reason for this mistrust was that the other side was accustomed to the political manoeuvring of Ismail Kemal Bey which was always oriented towards his own profit.

In addition to this, however, mistrust of all influence and power is typically Albanian.

Although Syreja Bey and his son were aware of all these difficulties from the start or came to realise them when they began their activities, they sent telegrams to all the major towns asking that envoys be sent to Vlora to discuss the future of Albania and the Ottoman Empire. These telegrams were signed not only by Syreja Bey but also by some of the leading representatives of the opposing party. Many replies were received over the next few days. Some were noncommittal, but most of the towns, in particular in the north, accepted the invitation willingly and without hesitation, and responded that they would set off for Vlora as soon as a date was set for the start of the gathering.

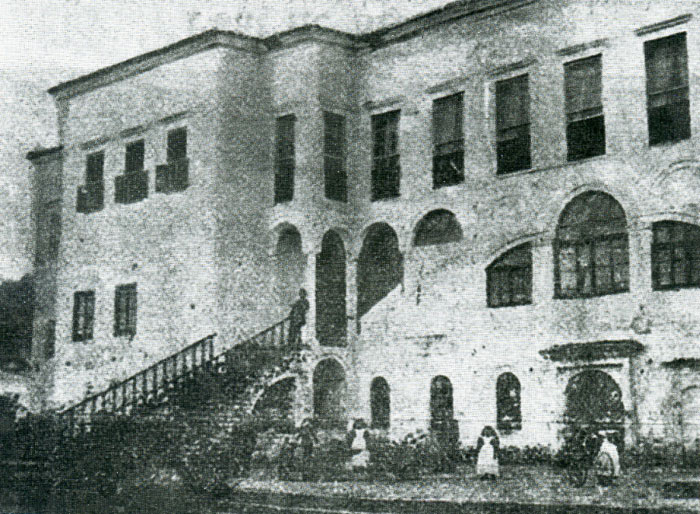

The selamlik (male quarters)

of the Vlora family estate in Vlora,

where Albanian independence

was declared in November 1912.

At that time, Ismail Kemal Bey was in Bucharest where he first received news of the preparations for the assembly. He immediately cabled his friends throughout Albania encouraging them to believe what they had been told and to care for the country’s future. Having heard of Ekrem Bey’s trip, he set off to Vienna without delay.

A foreseeable conflict, however, soon broke out between the leading officials in the town. Syreja Bey found it particularly trying because he was not used to the situation in Albania.

Despite long hours of tedious discussions, day and night, the men of Vlora were unable to reach any decision on a matter that was actually rather simple, that is, agreement on the day of the gathering and how it was to be organised.

After several days of this, Syreja Bey used the first opportunity to flee from these unpleasant, exhausting and futile conflicts and travelled to Durrës in order to consult with the northern Albanian leaders once again, in particular with Abdi and Murad Bey Toptani and Don Nikolla Kaçorri, whom Ekrem Bey had visited on his return from Vienna and informed about the general situation, and in order to prepare for the assembly in a town of northern Albania, if possible. Ekrem Bey, for his part, carried on with the negotiations in Vlora.

After visiting Durrës and Tirana, Syreja Bey continued on to Shkodra to come to an agreement with the leaders of the Catholic Albanians, but he was caught during the siege there and unable to leave the town for two weeks. When he was finally able to get out and discovered that a joint resolution had still not been reached and was being impeded by a myriad of minor details, he became extremely frustrated at the lack of understanding for his efforts and work and the insulting mistrust of many of his compatriots, and lost his patience. Sick and tired of the whole affair and no longer believing that it was feasible, he departed for Constantinople instead of going back to Vlora.

He thereby left his son in a highly precarious situation. Not only were the men of Vlora just as rebellious and lacking in understanding as they had been earlier, but the twenty-seven-year-old Ekrem Bey was unable to exert the authority he needed in a country highly influenced by Oriental ways. This situation may seem curious to those unfamiliar with Turkey, especially in conjunction with a man known by everyone in the country for his talent and spirit of self-sacrifice. Those, however, who are familiar with the Orient, will be able to confirm that reason and stalwart character are not enough to exert influence in the Muslim world. What is needed in addition is a moustache, because they hold a rather childish view that wisdom grows with the hairs of one’s moustache. This unfortunate attitude that causes so much youthful energy to go to waste and makes all decisions and endeavours in the Orient hesitant, vague, cowardly and senile, is so prevalent that older men regard it as shameful and indeed unthinkable to yield to the leadership of a younger man.

In Vienna, Ismail Kemal Bey learned of the departure of Syreja Bey, understood what had taken place, realised that he would now have no difficulty in taking over, and cabled his party, telling them not to do anything until he got back to Vlora.

This made the work of Ekrem Bey even more difficult in Vlora because he was now faced with open hostility from the supporters of Ismail Kemal. They told Ekrem Bey that they had not come to Vlora to sell their country to Austria and, in their naiveté or nastiness, even went so far as to suspect everyone around him of being in Austrian pay.

Of much greater significance than this base insult was the fact that, behind Ekrem Bey’s back, the supporters of Ismail Kemal who had signed Syreja Bey’s telegram, now sent a second telegram to all the towns, revoked the first telegram, and called upon the representatives of these towns not to go to Vlora, in spite of Syreja Bey’s original request.

As such, nothing changed. The situation was just as it had been three weeks earlier when Ekrem Bey first arrived from Vienna.

Despite all of this, Ekrem Bey carried on, at least in order to keep his word to the delegates of northern Albania and to those of some of the southern Albanian towns who were nonetheless willing to come, and to show them that he was doing everything he could for his country. Yet he knew full well that he would not be able to hold the league together without the return of his father.

On a joint trip to Fier, during which I had occasion to take part in political consultations at the home of the Virjonis [Vrionis], I could see for myself that this interpretation of the situation was right, because although Ekrem Bey strove for hours on end to explain the situation as it really was, it was impossible to convince anyone – except Kemal Bey Virjoni – of the necessity of acting swiftly and of founding a league. It was even impossible to make it clear to them that, with the Serbs in Monastir [Bitola], the Turks would most certainly be defeated. Despite all the explanations offered, their only reaction was “If Europe wants Albania, they will create it without our help; if not, our efforts will be in vain.” It was not possible to make these people understand how much easier it would be for Albania’s friends to represent and promote the interests of a strong and vociferous Albanian national movement on the international scene than it would be to feign the necessity of national independence for an indifferent Albania. This pettiness, timidity and lack of will may not surprise many people, but in this case, there was another aspect involved. The non-committal reaction was less due to a lack of understanding than to envy at the dynasty of Syreja Bey. Thus, that in a very typical Albanian way, public interest was sacrificed and shrouded by conflicts of a purely personal nature. The position of the Vlora family in its native mutasarriflik of Vlora was not to be denied and people were ready to recognise its authority under certain circumstances and to a certain degree – but only to a certain degree. Nothing was to be feared from Ismail Kemal Bey, who himself owned no property in the country and whose sons were unable to carry on any of the work he had begun. On the other hand, these fainthearted leaders believed that Syreja Bey and his dynasty, whose extensive estates alone gave him a certain weight in the country, would become too powerful if they allowed his son to rise to equal prominence with his father. They were fearful that his wealth, position, power and influence would be passed on to his son and would give this branch of the Vlora family a sort of hegemony. It is this that they were determined to prevent.

Early Albanian flag from the

collection of Ekrem bey Vlora,

now preserved at the

Institute of Folk Culture in Tirana.

As soon as we got back from Fier, word spread in Vlora that Ismail Kemal Bey would be arriving in the coming days with the envoys of the towns of northern Albania who had been waiting for him ever since Syreja bey’s first telegram that had called for the creation of a national assembly. As a result, the endeavour of Syreja Bey and his son was destined to come to fruition, though in a different form.

On that same day, a messenger brought news from Laberia that the Greeks had landed in Himara and had called upon the villages in that region to surrender. The Christian villages on the coast, where Orthodox priests had for years been active in spreading not religion but Greek national propaganda, were easily won over to the idea of belonging to Greece and surrendered immediately. The Muslim villages in the interior, however, decided to resist if assistance were to be forthcoming from Vlora. There were many people in the region around Vlora who were ready to take arms and march on Laberia, but none of the beys in the town was willing to lead them. Ekrem Bey thus decided to take over. There were several reasons behind this decision. Most of all, he only wanted to meet Ismail Kemal Bey when the latter’s plans and intentions were evident, so that he could position himself accordingly without losing his independence by any promises made in the heat of events. In addition to this, after weeks of intense political negotiations, he wanted to get away from the intrigues and backstairs politics for a while. Most of all, he was quite rightly of the opinion that the Greeks had to be actively opposed, not only for reasons of national pride but also for the sake of pure survival. If Greece were to take Vlora, no Albanian national assembly would ever take place. It was evident that the nation had to rid itself of the foe before they could begin talks on a government and an administration.

As such, Ekrem Bey withdrew to Kuç where he succeeded in persuading this and the other Muslim villages of the necessity of continued resistance to oppose the Greeks in active battle so that the latter would not get beyond the coastal villages which were protected by ship cannons. This was no doubt more useful than him staying back in Vlora where everything was ready and the whole town was waiting for the arrival of someone like Ismail Kemal Bey who, in Oriental thinking, was old enough to bring the harvest in.

There was fighting in the mountains. The two sides were separated by the Çika or Acroceraunian mountain range. Ekrem Bey’s men thrice penetrated the villages held by the Greeks and could have driven the foe, defended by only one canon, out of the country. They fought with extraordinary courage despite the snow, the cold and the impossibility of getting food supplies up to the pass, in particular to the men fighting under Ekrem Bey’s command who were far from their native villages. Reinforcements, however, soon arrived, including men from distant villages in Laberia. Albanian soldiers are often referred to as restive and obstinate, but this is only true to an extent. If Albanian troops do not fight well, it is certain that they do not have a competent leader and that this leader has not taken to the fore as he should. When a leader shares the difficulties and dangers of battle with his men, they overcome all fear and exhaustion. In this instance, the men from Laberia put up with all the deprivations without complaining and fought like lions, throwing themselves into enemy fire, because their leader starved with them and stood with them in the line of fire. For example, they tore down the Greek flag that had been raised in Pilur in an open area although they were completely exposed to enemy fire at close range. It was only the seventh one of them who succeeded in getting to it. The six of them before him died under Greek fire, and even the man who caught hold of the flag died as he was pulling it down. It is a tribute to the influence this commander had over his fighters that nothing was stolen in the enemy villages, because Ekrem Bey had asked him men not to touch anything, despite the fact that the men of Laberia are known throughout Albania for the inclination for booty. Only one blanket was taken, which had been spirited off by two men together. As they did not know how to divide it, they handed it over to Ekrem Bey. The fighting in Himara continued for months after Ekrem Bey’s return to Vlora but without the same élan. The only consequence of it all was that the Greeks were unable to advance any further and that the Albanians were unable to take Himara. […]

Despite bad communications, news reached Vlora, day after day, on Ismail Kemal Bey’s approach. It was said that he was in the company of a number of patriots who had been active abroad in recent years, particularly in Bucharest. It was also rumoured that Isa Boletini and his faithful supporters were on their way to Vlora. Word spread from mouth to mouth but, even then, no one in Vlora believed that the country was on the verge of declaring its independence.

Up to this point in time, there was a great desire for peace and order among those who had a basic understanding of the political situation, or better, among those who, by means of their wealth, had a more or less higher education and appreciated the advantages of public order and of good governance. After years of oppression under Abdul Hamid and constant uprisings, they now longed for normal relations so that Albanian landowners, like the landed gentry in other countries, could sit back and enjoy the profits of their land, so that Albanian handicraftsmen could concentrate on making money instead of fighting with their neighbours, and so that Albanian merchants, big and small, could carry on with the business of import and export without being impeded by boycotts, wars, blockades and other inconveniences. This longing for order crystallized in a wish for a great power strong enough to protect Albania from domestic and foreign foes, one that would be willing to promote the country’s advancement, even without political independence. It was to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy that they turned as it was to Vienna that they felt most closely attached. For this reason, the calmer elements among the Albanians, with the exception of the political leaders who understood the illusory nature of this wish, expected for weeks that Austria would soon land troops. Every time they saw a ship on the horizon, they believed it was an Austrian cruiser and started arranging for the landing.

This hope held out right until the arrival of Ismail Kemal Bey, but when he arrived, it was suddenly forgotten and replaced by intense curiosity as to what changes he would bring with him.

We waited for him for two days, but he arrived at night when everyone was sound asleep.

I will never forget the next morning, 28 November. I had just gotten up when I was called over to the selamlik. There I met Hydej Efendi, one of the most honourable aghas of Vlora. “Baroness, we know that Ekrem Bey has an Albanian flag,” he said to me. “Would you go and get it for us, please? It is going to be raised today as we intend to declare Albanian independence.”

I went and got the flag for them, the first Albanian flag. It was the one that Ekrem Bey had taken with him on his travels through Albania over the last eight years at a time when hardly anyone even dared to speak Albanian because they would have been arrested or banned from the country.

I was enraptured that day because I knew that Ismail Kemal Bey would not have taken such a step without having been encouraged by Turkey’s defeat in Europe. A man of his intellectual talents would not have thrown his country into such an adventure without being convinced of the outcome.

On that very day, the Albanian flag was indeed raised on the gate to the entrance of Selim Bey Vlora’s house.

Standing at the windows were Ismail Kemal Bey and all the deputies of the towns of northern Albania who had arrived with him: Abdi and Murad Bey Toptani, Sali Efendi Gjika, Mid’hat Bey Frashëri, Don Nikolla Kaçorri, Riza Bey Gjakova and others. A dense crowd had gathered in the garden. Mixed in among the Tosks were the tall, lanky Ghegs with shaven heads and white felt caps, each with a rifle in his arms.

The women in the harem waved when the flag was raised. An old man standing at the door of the house called out in a voice trembling with emotion: “I am ready to die now that I have seen this day dawn!” Many of the men present had longed for this day, and what sacrifice they had made for it!

When the flag was raised, everyone enthusiastically sang the anthem “Për mëmëdhen” (For the Motherland) to it. Then, Ismail Kemal Bey, Murad Bey Toptani and Don Kaçorri spoke to the crowd that clamoured to hear them. Personally, I was rather disappointed in their speeches. I had hoped that the leaders would speak out clearly about their plans and intentions. Instead of this, all the three of them said was that the flag had now been raised and that they would rather die than let the Serbs or Greeks into the country. This was a bit absurd in view of the fact that the Serbs had already advanced beyond Peja and were marching towards the sea. Indeed, many of the northern Albanian participants at the gathering had simply fled from them – an understandable and reasonable step – but it was still a flight.

At least we learned that day that a provisional government was to be formed which would hold power until the fate of Albania was determined by the coming European conference. We were also informed that Ismail Kemal Bey would be the chairman of the national assembly and Don Nikolla Kaçorri (an Catholic Albanian clergyman) would be the vice-chairman, which was proof that religious fanaticism had no place in Albania.

Not all of the Tosk deputies had arrived, but at least they sent word from several towns that they would be coming.

On that evening and, in particular, on the following two days, concern and scepticism spread, even among those who had been caught up in the initial enthusiasm. Many people could not overcome their mistrust of Ismail Kemal Bey. A very intelligent woman from the small middle class, for instance, said to me on the day he arrived: “We are afraid. We would be very relieved if Syreja Bey came with Ismail Kemal Bey.” Others told me: “I hope this man, who has never been very lucky, does not bring new destruction with him, – war and plundering.” This distrust of the person of the new president had to do with his past rather than with the events that were unfolding there […]

[Excerpt from: Marie Amelie Freiin von Godin, Aus dem neuen Albanien: politische und kulturhistorische Skizzen (Vienna: Josef Roller, 1914), p. 35-49. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP