| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

Aubrey Herbert

1912

Aubrey Herbert:

A Meeting with Isa BoletiniBritish public figure, diplomat and writer, Aubrey Herbert (1880-1923) was the half-brother of Lord Carnarvon of Tutenkhamen fame. Born of an aristocratic family, he attended Eton from April 1893 to 1898 when he went on to study history at Balliol College in Oxford. He worked as an honorary attaché at the British embassies in Tokyo (1902) and Constantinople (1904), and travelled extensively throughout the Ottoman Empire.

As a conservative candidate, Herbert was elected to the British Parliament in November 1911 and helped make the Albanian cause known there over the next decade. In 1912 and 1913, he travelled to the Balkans. At the time of the Conference of Ambassadors in London in 1913, he founded an Albanian Committee to guide the Albanian delegation in its negotiations with the Great Powers and to act as a pressure group to raise funds and draw attention to the appalling situation in Albania. This Albanian Committee evolved into the Anglo-Albanian Society (1918), of which Herbert was president, and finally into the Anglo-Albanian Association. It was in 1913 that Herbert first met Edith Durham with whom he collaborated in relief efforts. He was also a friend of Isa Boletini. By this time, he had become something of a national hero in Albania, and his name was being mentioned increasingly in connection with the vacant Albanian throne. From the end of World War I to his death, he served as a champion of the Albanian cause, acting, among other things, as an advisor to the Albanian delegation at the Paris Peace Conference.

Aubrey Herbert is the author of the posthumous volume “Ben Kendim, a Record of Eastern Travels,” London 1924, from which this extract is taken. The text focusses on his journey through Novi Pazar and Mitrovica in August 1912, and in particular on his meeting with Isa Boletini, whom he describes as the Robin Hood of Albania.

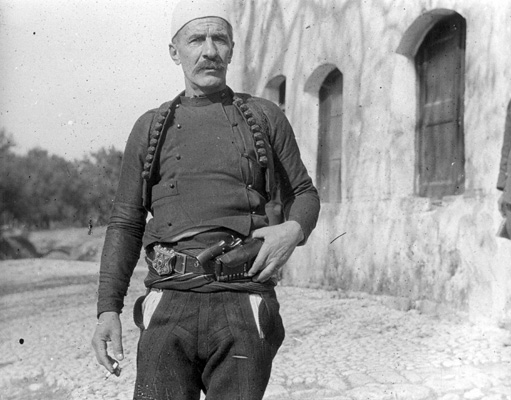

Albanian nationalist figure and guerrilla fighter. Isa bey Boletini (1864-1916) was born in the village of Boletin near Mitrovica. He was one of the great freedom fighters of Kosova at the turn of the last century. After the rise of the League of Prizren, he took part as a young man in the Battle of Slivova against Turkish forces on 22 April 1881. In 1902, Boletini was appointed head of the personal “Albanian guard” of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876-1909) in Istanbul, where he spent most of the next four years and acquired the title “bey.” He was loyal to the sultan, but, in 1908, he gave his initial support to the Young Turks. When Xhavid Pasha sent an army of 7,000 men to subdue Kosova in November 1908, however, he and a handful of friends put up fierce resistance. After their escape, Turkish troops burned his house down in revenge. In 1909 Boletini led fighting in Prishtina, Prizren and elsewhere, and played an important role in the general uprising in Kosova in the spring of 1910, where he held Turkish forces at bay in Caraleva, between Ferizaj and Prizren, for two days. During the first Balkan War in 1912, he led armed guerrillas in Kosova and later in Albania proper, in support of the provisional government which proclaimed Albanian independence in Vlora on 28 November 1912.

In March 1913, Boletini accompanied Ismail Qemal bey Vlora to London to seek British support for the new country. Historian Edwin Jacques reports the anecdote that “upon entering the British Foreign Office building to plead his nation’s cause, the security police asked him to remove the pistol from his belt and check it in the vestibule. He complied with no objection. Following the interview, the foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, accompanied Boletini to the vestibule where he put the pistol back in his belt. The foreign secretary remarked with a smile, ‘General, the newspapers might record tomorrow that Isa Boletini, whom even Mahmut Shefqet Pasha could not disarm, was just disarmed in London.’ Boletini replied with a broad smile, ‘No, no, not in London either,’ and he withdrew from his pocket a second pistol.” Boletini returned to Albania, where his troops defended Prince Wilhelm zu Wied until the latter’s departure from Albania. He was later interned in Podgorica where he is said to have been killed in a shoot-out.

Sunday, August 25, 1912. Novi-Bazar.—When I got up this morning, Ahmed came to tell me that a telegram had arrived from Issa Boletin, saying that if injury of any kind was done to me, dire vengeance would fall upon those responsible, so my status had now entirely changed and Jack and I were the heroes of the moment. I left the little dog, Paris, and his friend, a very sporting couple, in charge of one of the friendly Albanians. I gave Ahmed Effendi my revolver as a present, as I thought I was probably getting out of the troubled area, and should not be likely to want it again. He pulled out his silver-worked knife to give me, but I refused it. The town was in the market-place to see us meet and go off. It reminded me of going out for yeomanry training, except that the crowd was differently dressed. They were in scarlet-and-yellow jerkins, with red-and-black scarves and dark hoods, and we made a picturesque procession as we moved off, with advance and rear-guards and men riding on the flanks. We sometimes drove and sometimes rode. Rifaat, an immense man, with three brothers as big as himself, came with me. He said that he had, in honourable fight, killed twelve men that summer; that he was the right-hand man of the mutesarriff, that his three brothers had also been outlaws for the whole of the summer, and that his father had held a whole regiment at bay. He put his arms round my neck to say so. Some miles out of the town the warrior citizens halted and made a ring and everyone made speeches. I do not think I have ever seen such extraordinarily fine men physically. We all said what we would do next time we met, and they said that if trouble came they would come and seek my bessa (protection) in England. They looked like kings in rags. I said to one of the Albanians that I would learn to speak his language, as we had had to talk through an interpreter, who spoke Albanian. He answered magnificently, "Learn only the names of weapons and we can talk sufficiently.” Then most of them went back, but the escort stayed. Going on, we saw one band of Serbs to the south-east, but they sheered off.

The escort and I talked all the way. They all agreed that the murder of Ivan was a calamity and a disgrace. I said that things such as this hurt both Islam and the Christians. The gendarmes said it was the work of ignorant children. These people are, I suppose, the descendants of the Patzinaks who bothered the Crusaders so much. They told me the chief Albanian grievances. There were first of all too many officials and the new regime troubled them more than the old had done; secondly they did not like military service, though there was, no doubt, a good deal to be said for having military service with the Christians. There was also a great deal against it. The Moslems fasted and the Christians did not. The Christians drink and smoke during Ramadan. It was not Christianity that they minded, and that was shown by their readiness, they said, to obey foreign Christian officers. It was the difference of customs of natives. Coming down the Sanjak, I have met several Christian soldiers and they seem to get on very well with the Moslems. I offered one man baksheesh to-day, which he refused, saying, "We do this willingly for the State that we serve; we need no bribes.” The others told me that it was because they, the Albanians, were looking that he acted thus, not because he hated foreigners, or through devotion to duty. I am afraid that my escort would not win a prize for morals. Most of them have been in prison—not that that argues crime on their part—and those who have kept out have only done so by the help of their rifles. The gendarmes' complaints were the same as always—bad pay, too much work, no consideration, long exile; but the real Albanian complaint, first and last, is that their honour and freedom are not sufficiently considered. I have enjoyed this journey through the Sanjak quite enormously. The first part of it is dull and a little monotonous after the very sensational scenery of Bosnia. The second part of the journey is very rugged, and reminded me slightly of Southern Albania and the Pindus ranges, though there is more life. There are long stretches of range after range of mountains and valleys. One passes a few goats and sheep like chamois, and there are generally eagles high overhead or ravens croaking in the distance. Sienitza is high and flat. From Sienitza the country comes in a long sweep and looks fertile, and is fairly often cultivated. The road to Novi-Bazar is a good road. The town itself is like any Turkish town, perhaps a little more Albanian. Here the Turks are at present in power. I went to the telegraph office to send a telegram home, but could not do it, as the clerk-translator was away at Mitrovitza. There were, however, two Turkish officers there wiring immediately for more troops to go to the front, but the place itself was as peaceful as the Foreign Office, and had the same lack of passion. A couple of loungers, who had followed me in, and I, stood and listened to these official telegrams being dictated. Rifaat has been too tiresome. He is a turbulent ruffian, and I shan't be sorry when he is shot. I have never met a Turk or an Albanian who boasted of the men he had killed before. He has, I believe, twelve jaks (blood-feuds) and he hated walking with me at night in the town of Novi-Bazar, where he is out of his own district and could be killed, anyway for the moment, with impunity, but I must admit that he did walk with me, as he had given his word to do so. The driver, Hadji Salih, said, "Yureki kopuk dir amma namuzti bir adam—his heart is rotten, but he is an honourable man,” and he added, "God preserve me from falling into his hands.” He and his brothers are magnificent men to look at, like gigantic Arabs. I gave them a couple of liras and a knife. Ahmed Effendi was the best of the lot. His chief feat, of which he did not speak himself, was to kill a man and a horse at one shot last year. At Novi-Bazar I heard the explanation of the Kaimakam's presence at Sienitza when he was murdered. He had been sent for by the Vali of Uskub, to consult with him, and was crossing to Serbia, as the quickest way to get there.

Monday, August 26, 1912. Mitrovitza.—The country to-day was rather like Northern Italy, soft light and soft hills, with purple shadows on them. We started at six, and passed through a belt of purely Christian population. Generally here the creeds are mixed, but sometimes they are in belts. I was met by a lieutenant with thirty men from Mitrovitza. They had had an eight hours' ride to meet me, and would, of course, have another eight to return with me, in this tremendous heat and with a campaign going on. It is the most wicked waste. One man nearly died on the way. He had a fit. I wanted to give him brandy, but the others refused it for him. They were good Moslems. I had him, however, put into our cart. When we arrived at Mitrovitza, the driver Ibrahim, a converted Christian, refused to take him to hospital. I settled master Ibrahim pretty quick. Jack and I had nothing but a little cheese and sour milk from six this morning until eight to-night. Now we have yaourt (sour milk), the "butter in a lordly dish" which Jael gave to Sisera, with the intention of making him sleep before she murdered him. It will make us sleep to-night. It is a dish that makes centenarians and saints. Here nobody is talking of anything but the fighting all along the frontier, which is making the people mad. Every karakol (guard-house) has gone up in flames along our frontier; Moykjovitch and Berana are the last big fights.

Tuesday, August 27, 1912. Mitrovitza.—I went again to send a telegram and found the Turkish official extremely rude. He said that no one here knew French and no telegram could be sent. I answered as rudely. I went off to the Kaimakam, Halid Bey, a delightful man—like an English curate—who has seen thirty years of war. As we sat talking, in came the rude Turk, puffing and very angry. When he saw me beside the Kaimakam, he proclaimed himself an unhappy man and said that I had taken words to myself which were intended for another, a quite poor man standing beside me. He said nothing was easier than to send a telegram in any language. I met the Russian Consul in the street. He asked me to play bridge. I don't know the rules.

I shan't forget the last time when I came to Mitrovitza, in the very heart of winter, after the revolution. It was the time of the great prediction of the future of Turkey when its future, in spite of what had happened, still looked golden. I rode to Ipek, in cold such as I had never known, across the most wonderful country. From one mountain one could count a hundred valleys. We slept twenty or more in one room of an enormous khan, with a great fire blazing on the hearth. Even then there were signs of trouble coming. The hanji, a huge and fierce Albanian, said to me, "Who knows how all this business is going to turn out?” At Ipek I dined with the Governor and an Albanian Bey, “Sword of the Faith.” I asked him at dinner if he had ever seen war. "By God,” he said, "of course I have. I am twenty-four.” "When was the last time?” said I. "Why, when we drove His Excellency here out of Ipek,” he answered. The Turk got angry and said, "Lack of manners is not necessary.” Now "Sword of the Faith" has again been playing a part in war and politics. He has been a strong Committee-man and Ipek did not rise when the general insurrection took place, though the citizens of that town took possession of the powder magazine and of some four thousand rifles; consequently, there was general anger against Ipek. Riza Bey of Djakova, Issa of Mitrovitza and the Albanians of Prisrend are all furious, and when the bessa ends there may be fighting. Meanwhile, "Sword of the Faith,” perhaps from patriotism, perhaps to regain the favour that he has lost, has gone off to the frontier and is fighting Montenegro.

I met the Austrian and the Russian Consuls together. They were not very friendly to each other, though very nice to me. When we were alone, the Russian said that the Austrian annexation of the Sanjak would certainly be a casus belli. He told me that his life had been threatened. In the afternoon, I went to the factory of Nedjib Bey Draga, and saw his brother and many others. They all of them think that the Committee is beaten, but they do not want autonomy. It is freedom, more than independence, that they are after. There is no doubt that the C.U.P. have made an awful mess of the Albanian business, and so have their generals. These people can be handled and have very fine things about them.

I saw Djavid Pasha, who was friendly and put a room at my disposal. He was not very communicative. I told him what had happened at Sienitza. His own position is, of course, very difficult here, for the Albanians have fought the Turks to a standstill, and it is this Montenegrin trouble that is largely responsible for the quasi-peace that is existing between the Turks and the Albanians to-day. Even now, the Albanians sent between half a dozen and a dozen Turkish officials packing from Mitrovitza the other day. I said to the general that Issa Boletin had telegraphed about me to Sienitza and that I wished to thank him for doing so, to which he agreed politely.

Here are six of the most important Albanian points:

1. The Albanians to have schools where they like, and Albanian taught in them.

2. Officials in Albania must know Albanian.

3. More attention to be paid to religion.

4. Guns for all, Christians and Mahommedans alike.

5. Agricultural schools, under certain conditions.

6. The impeachment of Hakki Pasha.I think the condition of Mitrovitza is very bad and dangerous to the Christians, owing to all this fighting; but the good-class Moslems are honest and honourable men who are doing the best they can. They say that Mehmed Pasha will be re-elected; Amir of Akova will not. There are many differences of opinion, more than quarrels, amongst the Albanians themselves. They are all anxious to tide over this extremely difficult time, so full of uncertainty and danger to them all. They think that the Turkish Government will grant their demands. I saw Don Nikola Mazarek, a most delightful Austrian priest. The murders going on between here and Ipek are bad and of a very brutal kind. Then I went to dine with the Austrians. In the middle of dinner I received a mysterious message to say that Issa Boletin was waiting for me outside the town. I thought it quite useless to make a secret de Polichinelle. The Austrians knew what had happened at Sienitza and would certainly know of my meeting with Issa, so I told the truth, that I was going to thank him, and left.

It was a perfect night outside, with an enormous full moon, in a cloudless sky. Hadji Salih was waiting with an unnecessary lamp, and we walked quickly through the streets outside the town to a khan, where Issa had come to meet me. He was surrounded by numbers of his wild Albanian mountaineers, covered with weapons. They made a fine picture in the moonlight. I waited in the courtyard. One or two of them came up to talk to me; they were generally very aloof, but seemed to be tingling with excitement. Then I was shown upstairs, and outside on the landing was another crowd of beweaponed Albanians. The walls were all hung round with arms. I went into a fair-sized room, where I found Issa Boletin, a very tall, lithe, well-made Albanian, aquiline, with restless eyes and a handsome, fierce face, in the Gheg dress. One of his sons, the eldest of nine, he said, a very handsome boy, stayed in the room to interpret in Italian, which proved unnecessary. He turned the others out, except for one man, and we sat down on a low divan in the window. I first of all thanked him for having sent the telegram, and said I thought it was a great pity that the poor Kaimakam had been murdered. With this he entirely agreed, and said he was sorry that I had been put to any inconvenience. The people had been through terribly hard times and could not be expected always to be informed or to act wisely. He said the Albanians loved England and he hoped the English liked the Albanians. I asked, "Did the Albanians want autonomy?” "No,” he said, "they did not; what they wanted was not to be interfered with.” "Do you want union,” I said, "between the north and the south?” "Well,” he said, "we are one people" but he went on to say that the union would not be advantageous to the north, for the Tosks, the southerners, were more educated and clever than the northerners. Albania wished to be under the Sultan, but the Albanians must have arms to defend their country, and these arms had been taken from them by the foolish Turks. When the bessa (truce) ended at Bairam, he could not say what was going to happen. It was all incalculable. The Albanians would have liked to have fought the Italians. (There they joined with the Turks.) But they could not do this without a fleet. I said there were great difficulties in the way of ending the war, but its prolongation meant the danger of the disruption of Turkey and therefore great danger to Albania. Surely the best policy for the Albanians was to make an honourable peace as quickly as they could? He asked me what was our British interest in the Turkish-Italian War? I said our interest was that we were the greatest Moslem power and that we wanted to end a situation that was very painful to many of our Moslem fellow-subjects. Also, the disruption of Turkey would mean to us that coasts would be taken, forts and harbours made by other countries not as friendly to us as Turkey. At this point a couple of shots went off under the window. I was interested in the conversation and paid no attention. Issa pulled back a little curtain and looked out into the moonlight. As he did so, a dozen shots rang out just outside. Instantly his clansmen swarmed into the room, taking arms down from the wall. They walked upon dancing feet and their eyes glittered. Issa jumped up with a rifle in his hand and said to me, "The house is surrounded by the Turks. I am going to fight my way out.” I said to him, "This is not my quarrel, but I will come with you, and if you are taken, the Turks will not shoot you if I am there.” He said. "No, you are my guest. My honour will not allow this thing. You protect my son.” Issa and his men poured out. Some stayed and kept me in.

Kosova warrior Isa Boletini, June 1914They were back again almost at once. It had, apparently, been only a brawl outside—Turks, they said—and nobody hurt. I am very glad that I saw it. It was wonderful, the way in which the clansmen formed round Issa Boletin. They were like men on springs, active and lithe as panthers. It is no wonder that these people have got these bright, restless eyes, for a slow glance must often mean death to them.

This interlude rather upset our business talk; though the house had not been surrounded by the Turks, they were obviously nervous, after what had happened. Issa spoke again of the Albanians’ relations to the Turks. They—he was speaking for his kind— admired the Sultan and did not wish to leave his rule. What else for them was there, but to be dominated by Serbs and Montenegrins? He asked me if, when I went back to England, I would do what I could to help his people. I said that I would most gladly do all in my power, because I admired the Albanian people and I liked and admired him very greatly. We then said good-bye and I walked back, the Albanians accompanying me until we came to where the Turkish soldiers were waiting. The Turks walked back with Hadji Salih and myself to the municipal room which Djavid Pasha had given me.

THE ALBANIAN COMMITTEE

At the conclusion of the Balkan War, when Turkey-in-Europe was shattered, refugees, rather than representatives, came to England to make the desperate case known. The representatives from Macedonia, who had been accustomed all their lives to murder and brutality, still had a pathetic belief in the justice of the Great Powers. They could not realise that the world would not admit that it had any obligation to incur risk or expense in healing wounds or repairing ruins. England might be ready to go to war to protect her own people or for her own ends, but she was not prepared to take up arms for a mosaic of mixed and broken peoples. The Macedonians asked for mercy. It was not fair to expect it, for Prime Ministers and Chancellors of the Exchequer are not selected for the qualities that adorn knight-errants. The Great Powers were animal in their lusts, Pharisees in their aspirations.

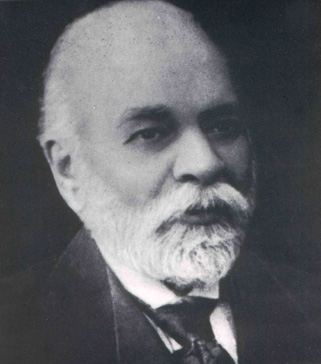

The Albanian Deputation arrived, composed of men of three different creeds—Orthodox Greek, Catholic and Moslem. At the head of it was Ismail Kemal Bey, a kindly and a versatile man, whose life had been a long and a precarious see-saw. His weakness lay in his circumstances and in his affection for his children. If he was tortuous, it was because it was difficult to be straight in his position. Impecuniosity was his taskmaster, and upon occasion he had to reconcile inconvenient convictions with convenient conduct, to the prejudice of the former.

He was the disciple of Midhat Pasha, Governor-General of Beirout, Governor-General of Crete, nominated Governor of Tripoli, Counsellor of and refugee from the Sultan, editor, Anglophile, friend of Chinese Gordon, child of adventure; he was also a tired and broken old man, advocate of a broken country.

He was an excellent raconteur, and I admired his stories of himself and of others. Once, after he had fled, as David from the wrath of Saul, before the anger of the Sultan Abdul Hamid, there had been a documentary reconciliation between them while he was abroad. The Sultan had offered to make him extra-Ambassador to all countries—so said Ismail Kemal, who did not accept this unusual post.

Upon another occasion, when the New Testament had been translated from sonorous, traditional Greek into Romaic, a riot had occurred in Athens, and some tens or scores of Athenians had been killed. The Press of Athens had then requested Ismail Kemal to explain this phenomenon to Europe, and to exculpate the Athenians. How far he succeeded, I do not know, but the behaviour of the people of Athens in their sanguinary protests against the translation of the Bible into modern Greek is not as unreasonable as it appears. A colleague of mine in Constantinople said, "Well, would you like to see written in the New Testament, instead of ‘And it came to pass,’ ‘Now this is ‘ow it ‘appened'?”

Ismail Kemal BeyI knew Ismail Kemal Bey in his old age, when he was like a wise and benevolent tortoise. He had in him a real liberalism that never faded, but which became encrusted with the slovenliness of his own nature, and the weary deviations from straightness to which circumstances forced him. He was canny, and he was able, and he had the power of phrasing his canniness crisply. If Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman had married a Bulgarian peasant and throughout his life had been forced to avoid the bastinado by placating Abdul Hamid, and had often found it difficult to obtain lodging for the night and to pay for it, he might have had much in common with Ismail Kemal Bey.

Other outstanding figures of the Albanian Deputation were Monsignor Fan Noli and Faik Bey Konitza, who represented the Vatra, the Federation of the Albanians of America. His brother, Mehmed Bey Konitza, now Albanian Minister in London, had been in the Turkish Diplomatic Service. Monsieur Philippe Nogga was a Catholic, and was as devoted to music as to politics.

The most picturesque figure of the Deputation was Issa Bey Boletin, the Robin Hood of Albania. He was an uneducated man, with a great and a just reputation for courage and resource. His deeds had become legends, and his escapes from Turks and Serbs, fables. He was lost and homesick in London, for he could not speak a word of English. He used to spend many hours in my house, drinking Turkish coffee. I constantly received at the House of Commons agitated telephone calls from my wife, and, on returning, I often found her and Issa speechless, but bowing to each other at short intervals.

The question of the partition of Albania was canvassed in the Press. A public meeting was called at the Connaught Rooms, and a Committee formed, of which I was made President. Those who took the principal part in the work of the Committee were Mr. C. F. Ryder, Mr. Mark Judge, Mr. J. C. Paget and Major Paget. Major Paget, who had lived at Scutari, and I were the only two who had actual acquaintance with the country; the others were prompted by a generous love of freedom. Later, Miss Durham, who had devoted years of work to Albania, and whose name is a household word from North to South, joined us, and Captain Evan MacRury.

We had continuous and intimate relations with the Albanians, and we were, I think, instrumental in obtaining advantages for the country which she would otherwise have lacked.

The Albanians who came to England produced an excellent impression. Upon one occasion, Mr. Lloyd George lunched with me, to meet them, and after lunch Toni Precha, of the Albanian Restaurant, and I acted as Interpreters between Issa Bey and the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

"Tell him,” said Issa, "that I am a mountaineer, as he is, and that I know that his heart is kind to those who suffer.” He wound up fiercely with,” And say that when spring comes, we will manure the plains of Kossovo with the bones of the Serbs, for we Albanians have suffered too much to forget.”

I thought it wise to soften the last phrase, but Mr. Lloyd George was delighted with the tall highlander, in whom he thought he recognised a kindred spirit, and was kind to him.

It was not only Mr. Lloyd George who was kind at that time (though never after) to the Albanians; there were many others. Long after Issa had returned to Northern Albania, I read in the newspapers that he had been captured by the Serbs in a guerrilla fight. I knew the Serbs and their way of dealing with their prisoners, and felt sure that his obituary notice would soon follow, and I hurried to the Foreign Office.

The Foreign Office said, quite reasonably, that they were not in a position to take any steps, but that if I was anxious to save the life of my friend I had better persuade some great man to plead his cause. I went to Lord Cromer, who said abruptly,” Now, what is all this business about? Is it politics, or is it a case of helping a friend of yours? If it is a friend of yours I will do what I can.” I said that it was a case of helping a friend of mine, who had been very good to me, and who would certainly die unless there was immediate intervention on his behalf. We then drafted a telegram to the following effect:

“To His Majesty, King Peter of Serbia. It is reported in the Press here that the Albanian Issa Bey Boletin has been made prisoner by Your Majesty's troops. Issa Bey Boletin was in London for a considerable time, and gained the respect and confidence of many distinguished people, and I venture to ask Your Majesty to show the clemency of strength, which will surely be appreciated.—cromer.”

The next day, when my morning papers arrived, I was glad yet horrified to read the following account:

“Yesterday it was stated in the ---- that Issa Boletinatz had been taken prisoner by the Serbs. The contrary appears to be the case, This noted leader of banditti has inflicted a heavy defeat upon the combined forces of the Serbs and the Montenegrins.”

I was very glad to know that my friend was alive; but I regretted having induced Lord Cromer to send a telegram that must have surprised King Peter. Later in the day Lord Cromer called me up on the telephone and said, with some asperity, “Why did you get me to appeal for this conqueror?” It was like Lord Cromer to lend his generous help in all ways to the younger generation. His kindness to his juniors was unending. I had many talks with him on the possible future of Albania, always hoping that another such as he might make of it a white Egypt.

The Albanian Committee did what it could to entertain, besides politically helping, the Albanians in England. One afternoon Issa Bey came with us to the zoo. As we drove down Regent Street, there were posters up,” Assassination of Niaisi by the son of Issa Boletin.” The members of the Albanian Committee who had not been in Albania were more surprised, and perhaps more shocked, than I by these tidings. They believed that this must be another libel upon a defenceless people.

“Tell him,” they said, “what is on this placard.”

I said to Issa Bey, “It is written on those walls that your son has killed Niaisi. Do you believe this?”

"What difference,” answered Issa cautiously, "is it going to make to me if this has happened?”

I said, "None. We don't like murder in this country, but one cannot be blamed for what one's relations do.”

“Then,” said Issa, “I think it is highly probable. I know my son was as determined to kill Niaisi as Niaisi was to kill him.”

We went on to the zoo, and when we had been round, Issa said: "You have all things in cages here, except the Devil. I like freedom.”

In the House of Commons he produced a great effect in his national costume, for none could look at him without admiration. He was much struck by Lord Treowen, who met him in uniform, and was very anxious to take him, willy nilly, back to Albania. He made many friends, who showed him the glories of London. "And yet,” said he to me, "grand as it all is, and kind as you English are, I would not change this for my own rocks and rivers.”

In the end, Issa Boletin was murdered while he was a prisoner at Podgoritza. He had the simplicity of a child and was a strong man of consistent courage, and was always true to his salt. He made one understand the gentleness as well as the roughness of the Middle Ages. I heard the account of his death from a companion. The quarrel was not his. He went to the rescue of a nephew, who had foolishly sought trouble. Issa killed eight men before he died. He fired quite steadily, badly wounded, from the ground, telling his friend, a civilian, how to take cover from the Montenegrins. Those who were his friends will not forget him.

[Extract from Aubrey Herbert: Ben Kendim, a Record of Eastern Travel (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1924), p. 198-213.]

TOP