| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

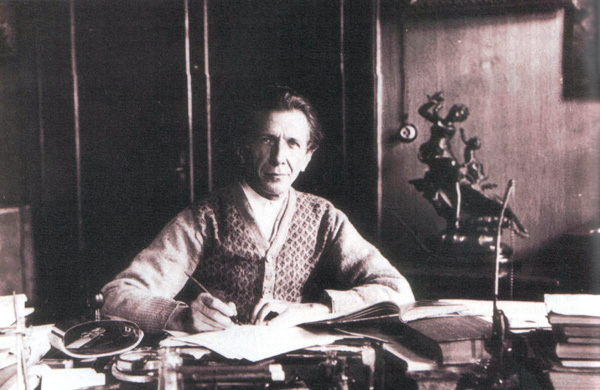

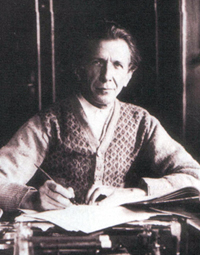

Milan von Šufflay

1912

Milan von Šufflay:

Mediaeval AlbaniaCroatian historian, Milan von Šufflay (1879-1931), was born in Lepoglava, southwest of Varaždin, and studied history and classical philology at the University of Zagreb. From 1904 to 1908, he worked for the national museum in Budapest and, from 1912 to 1918, was professor for medieval history in Zagreb. Šufflay was forced into early retirement for political reasons in 1918 and lived thereafter as a publisher in Zagreb. He was often in open political conflict with the new Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and, in 1921, was sentenced to three and a half years in prison. In 1928, he was offered the chair of southeast European history at the University of Budapest, but the government in Belgrade refused to let him accept the position. He was murdered by two Serb police agents in 1931.

Among Šufflay’s publications of Albanian interest, mention may be made of “Povijest severnih Arbanasa” (History of the Northern Albanians), Belgrade 1924, “Städte und Burgen Albaniens hauptsächlich während des Mittelalters” (The Towns and Fortresses of Albania, Primarily during the Middle Ages), Vienna 1924; and “Srbi i Arbanasi: njihova simbioza u srednjem vjeku” (Serbs and Albanians: Their Symbiosis during the Middle Ages), Belgrade 1925; as well as numerous articles. Together with Ludwig von Thallóczy and Konstantin Jireček, he published the important two-volume collection of Albanian historical documents entitled “Acta et diplomata res Albaniae mediae aetatis illustrantia” (Acts and Diplomatic Affairs illustrating the Middle Ages in Albania), Vienna 1913, 1918, covering the years 344 to 1406 A.D.

The present article was first published in a Viennese newspaper in November 1912, at a time when Serb forces had conquered Kosovo and occupied much of Albania. In it, Šufflay paints a picture of Albania in the Middle Ages with a view to showing that Serbia had no historical claim to the country.

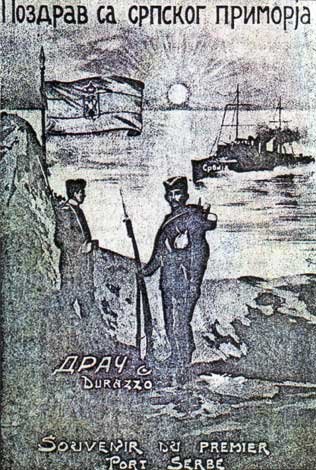

In order to justify Serb claims to Albania, in particular to the ports of Durazzo [Durrës] and Alessio [Lezha], Serb politicians bring forth primarily historical arguments. According to Pašić and Gruić, Albania has no right to autonomy, the Albanian Malissors are actually Serbs, Albania belonged solely to the Empire of Dushan, and Durrës, Lezha and San Giovanni di Medua [Shëngjin] were formerly only Serb ports. To put it briefly, all of Europe should be aware that the Serbs want only that part of Albania that they once possessed exclusively.

It is not my purpose here to investigate the psychological reasons for the preference for history which southern Slav politicians seem to have, nor to examine and criticise the curious justifications construed by the southern Slavs for their historical claims. Nor do I wish to delve into the issue of the extent to which historical factors should be taken into consideration in the coming division of European Turkey. The purpose of these lines is to draw an objective picture of Albania in the Middle Ages (before the arrival of the Turks) so that it is obvious to everyone: 1) that the Serbs are not the only ones who could raise historical claims to Albania, 2) that there were moments in Albanian history that speak in favour of annexation and others that speak in favour of Albanian autonomy, 3) that Serb politicians would have done better not to mention a historical claim to the main Albanian port of Durrës that they intend to conquer.

Mediaeval and modern Albania cannot be defined in rigid geographical terms. Initially (up to the 13th century), the word Albania was associated with a small territory around the castle of Kruja. It gradually spread to include Vlora and the mountains of Himara to the south, and Antivari [Bar] and even Cattaro [Kotor] to the north. In writings on history, Albania then became a conventional term to refer to the rectangular mountainous territory between Bar, Prizren, Ohrid and Valona [Vlora]. This is a region in which the original ethnic strata (Illyrians, Thracians) were almost entirely submerged under new formations of Greeks, Romans and Slavs, like ivy spreading over the granite monuments of a formerly great nation, the Illyrians. The word Albania had been used to describe the middle of this rectangle since ancient Illyrian times. The capital of these tribes was the town of Albanopolis (mentioned by Ptolemy), from where the term spread in the second half of the Middle Ages as a result of the brimming expansion of Albanian mountain herdsmen in scattered, but ethnically homogeneous groups to create modern Albania out of the Arbanon of the Byzantines, the Raban of the Serbs, the Regnum Albaniae of the Angevins, and the Albania of the Dalmatians and Venetians. It was a primarily ethnographical term, though its southern confine was difficult to pinpoint.

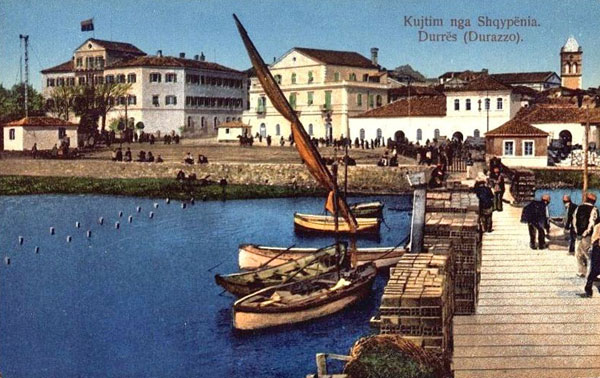

Coloured postcard of Durrës, ca. 1913This region was always a borderland par excellence, a frontier between languages, religions and political powers. It was a product of east and west, a fusion of the ports of the Latins and the Greeks, or an amalgamation of the Roman and the Byzantine worlds, that was in direct contact with the barbarians - the autochthonous Albanians and the advancing Slavs. Here we encounter chieftains of the Albanian tribes who, side by side, bore Byzantine titles such as protosebastos and sebastos, the Latin titles comes and miles, Slavic titles such as kaznac and vojevoda. The Durrës region was the point of contact between the three mediaeval languages of administration and official documents: Latin, Greek and Slavic. Even today, all kinds of Balkan costumes are to be found in the Vilayet of Shkodra: Greek, Romanian-Bulgarian, Bosnian-Dalmatian and Serbian-Montenegrin. Catholicism was in a perpetual struggle here with Orthodoxy. The Orthodox Metropolitan of Durrës took part in the synods in Constantinople, whereas his suffragan, the Bishop of Kruja, served in the interior of the country as a confident of the pope during the revolt of the Albanian princes against the schismatic king of the Serbs (1319). The allegiances of Albanian dynasties often fluctuated between the two churches, and later between Catholicism and Islam.

It is therefore no wonder in the age of Byzantium that, as this region was susceptible to both eastern and western designs, the Theme of Dyrrhachion became a focal point for schemes and military endeavours undertaken against the Slavs to the northeast and against Italy. For this reason, too, mediaeval Albania almost always served as a base of operations for the western powers to attack Byzantium. The Normans and the Neapolitans also focussed their attacks here. When Europe, under Pope John XXII, was envisaging a crusade against Palestine, the Archbishop of Antivari, the Dominican Guillelmus Adae, a visionary of western thinking, was compiling political observations in his Directorium ad passagium faciendum (1332), in which Albania was to play no insignificant role. Thus, over a hundred years before Scanderbeg’s memorable struggle against the Turks, the minds of many thinkers in Europe were attracted now and again to the strategic importance of Albania. It was only in the age of Scanderbeg, whose uprising was followed throughout Europe with great interest and was indeed actively supported, that people became more generally aware of Albania’s significance. The country became famous, due to its geographical position. Scanderbeg’s struggle was a borderland epic, the final cantos of which are still being sung.

But Albania is more than just a borderland. It is, in fact, the quintessence of the Balkans, a land that evinces all its Latin, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Italian and Slavic nuances. Here we can still come across ancient features that reflect the early ethnic composition of the Balkan Peninsula and that gave rise to the common characteristics of the Balkan languages and peoples in the Middle Ages.

Many of the above-mentioned characteristics of mediaeval Albania are to be found in the country today – a borderland and a quintessence of the Balkans, ethnic and cultural features that speak historically for the country’s autonomy and independence.

Even the political history of pre-Turkish Albania offers us a number of points that could be interpreted as the nucleus of an autonomous or independent State. Firstly, the eleventh-century Byzantine Theme of Dyrrhachion, ruled over by a Dux, was transformed by the Venetians (1204) into the Ducatus Dyrrhachii and by the Angevins (around 1272) into a Regnum Albaniae. Scanderbeg’s war made the concept of an independent Albania known throughout Europe, and there are indications that the idea of a Regnum Albaniae was still present on Albanian soil in the 17th century. Secondly, in the 13th century an Albanian dynasty (Principes) arose in and around Kruja (1200 to 1250). It carried on for several generations (Progon, Gin, Demetrius, Golem) and, although it was submerged (perhaps only to our eyes) under pressure from foreign powers, it resurfaced immediately on the collapse of the Serb empire and took on new names (Thopias, Dukagjini etc.).

Though it must be said, in general, that historians never viewed today's Albania as a unified political State, it is also true that history acknowledges at the same time that it belonged to two or three larger unified States, such that, from a historical perspective, none of the modern powers can lay an exclusive claim to Albania.

Greetings from the Serb coast. Durrës,

souvenir from the first Serb port.

Serb postcard, ca. 1913The fluctuation of the various spheres of power in mediaeval Albania can best be understood by following the political rise and fall of individual Albania towns. It would perhaps require too much data to create a detailed graph of such developments. Suffice it to note here that northern Albania with the town of Scutari [Shkodra] was under Serb rule, as were its much-visited port of Saint Sergius, S. Serzi [Shirq] at the mouth of the Boyana [Buna], and the settlements of Antivari, Dulcigno [Ulqin], Svač, and Drivast [Drisht] from the 11th to the 15th centuries in one form or another, as Regnum Diocliae, as part of the kingdom of the young kings (reges iuniores) and a possession of the king’s spouse, and later under the Montenegrin family Balšić. At the same time, central Albania around Durrës (in 1040 the town was temporarily in the hands of the Bulgarians) and southern Albania around Vlora were initially under Byzantine rule, then for a short time (1204 to 1213) under Venice, and then under the Despots of Epirus, who gave these towns to Manfred of Sicily in 1258 as a dowry, until in 1272, they came under the sway of the Angevin kings of Naples. Dushan, king of Serbia, was able to conquer all of the interior of Albania and the town of Kruja in 1343, as well as Vlora and Janina in the south, but Durrës itself remained in the hands of the Angevins (at that time, Durrës was under the nominal rule of King Louis of Hungary). In 1368, Durrës fell, though not to the Serbs, but to the Albanian dynasty of Charles Thopia. Later, though only for a brief period, Durrës was in the possession of Thopia’s enemies, the Balšić family, and in 1385 Balša II bore the title of Duke of Durrës. In 1392, however, Durrës was surrendered to Venice, not by the Balšić, but by George Thopia. In 1396, the Balšić dynasty offered to Venice the towns of Shkodra and Drivast. The republic wondered for a while whether its acceptance of these towns would violate its peace agreement with Hungary (si intromittendo dicta loca contrafaceremus paci Hungariae). Lezha, of whose earlier fate we know little, fluctuated in the second half of the 14th century between Serb and Albanian rule, but then fell, like Durrës, to Venice, not out of the hands of the Serbs but of the Albanian dynasty of Dukagjini. Later, it was in the possession of the Castriota, who in origin and custom were certainly not Serbs. The only town that fell to the Turks (1417) directly from the Serbs, as a relic from the time of Dushan, was Vlora (Medua is little referred to in source material before the time of Scanderbeg as it was not much used as a harbour in the Middle Ages). The only town that actually never belonged to the Serbs was Durrës, the port of which is now claimed by the Serbs for historical reasons!

[Das mittelalterliche Albanien, first published in Neue Freie Presse, Vienna, on 28. November 1912, p. 26 sq. and reprinted in Illyrisch-Albanische Forschungen, edited by Ludwig von Thallóczy, Volume 1 (München & Leipzig: Düncker & Humblot, 1916), p. 282-287. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP