| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1913

Egon Erwin Kisch:

The Shelling of Shkodra and the Burning Down

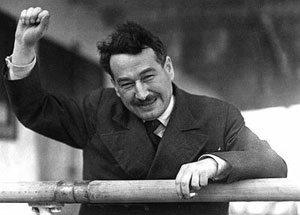

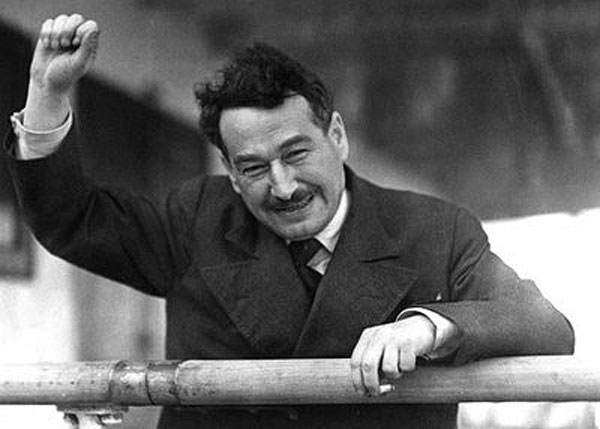

of the BazaarEgon Erwin Kisch (1885-1948) was a German-language Jewish writer from Prague who became well-known for his reportage journalism during the years of the Weimar Republic. He lived primarily in Berlin where his reportages were collected and published in the book “Der rasende Reporter” (The Raging Reporter), Berlin 1924. With his strong communist leanings, Kisch successfully cultivated the image of a witty and vivacious reporter on the move, and he was widely read, especially in left-wing circles. His works were later banned and burned by the Nazis. The collection, “Der rasende Reporter,” contains among other things a first-hand description of Kisch’s visit to Shkodra just after the old town burned down during the Montenegrin assault in the spring of 1913.

Egon Erwin Kisch (1885-1948),

photo taken in Melbourne in 1934.11 May 1913A pall of smoke is our destination, where fire raged this morning.

The steamer leaves the Montenegrin coast and sails down the estuary of the Rijeka River as it widens into Lake Shkodra. The lake is teeming with vegetation – trees standing in the water up to their tops, leafy plants floating on the surface of the water and tall-rising rushes. The ship ploughs its way through the flora, down a narrow channel marked out with wooden poles on the two sides and, after a few zig-zags and sharp curves, it enters the lake. In the distance are the mountains of Albania, between which looms a man-made cloud. We pass by Lesandro where until 1877 the largest Turkish fortress stood, and Grmosur, the location of Montenegro’s prison. Two hours’ later we are in Virpazar where we change boats and board the Neptune for Shkodra. To our right are the steep cliffs of the Krunja range, sombre and rugged, and in the distance are Tarabosh and the village of Ckla where Crown Prince Danilo received the delegates of Essad Pasha this week. Next come the villages of Zogaj and Sirocki Vir [Shiroka] where, not long ago, thousand of shells flew daily over the roofs of the houses from the artillery deployed on Tarabosh. Then come the Bardanjol range and the Bertica Mountains.

Out of the water rise two funnels of a sunken steamer and its stern. Triangles hang in the water from a thick masthead – the remains of a sailboat that was fired at from the mountains. Then the mast of another wreck appears in the water. How many people drowned here? The Turks erected kilometres of barbed wire fencing along the coastline and even into the water to prevent ships from approaching unseen.

We are now in the shadow of the fortress of Shkodra and the Mrnjacvica ridge that rises over the Bojana River. On the parapets fly the victorious blue-red-white banners of Montenegro. Below it is the old town in a pall of smoke in which the final flames are still flickering.

The Neptune casts its anchor not far from the place where Lake Shkodra flows into the Bojana that discharges into the Adriatic. Large barques piloted by unkempt Albanian lads jostle and hasten towards the steamer to pick up all the disembarking passengers and, at a cost of one piaster, to row them to the Bojana wharf. We then proceed past long lines of corn lofts and suddenly find ourselves in the main street, the “Tepe” of the old bazaar.

This was the site of the great conflagration. For months, with its jumble of shops and stalls in narrow allies and stuffy market halls, the bazaar withstood the artillery fire from Tarabosh and Bardanjol, and this at a time when there was no running water or fire-fighting equipment. Yesterday, however, the second day since the end of the siege, a cigarette butt or some glowing coals transformed the eight hundred little shops into a blazing torch. The flames rose so high that we could see them in the distance, from other side of the lake.

Yesterday, everything here was full of life. Today there is nothing but death. Where goods were once piled are now heaps of ashes. Soldiers have sealed off the entrances to what is left of the smoking bazaar. All that remains are the side walls. Amongst the rubble are shattered bricks, molten tin from bowls and basins, charred leather, burst cabinets, soot-covered fragments, smelly tobacco, gaping ceilings, tattered trimmings, destroyed kitchen equipment – a worthless pile of objects once offered for sale and now picked though by the last remaining beggars. The fire spared nothing. Even the tin clasp of a wallet lying on the flagstones is bent. The molten copper coins lying beside it were once hard-earned cash.

Steamer on Lake Shkodra

(Photo: Marubi, ca 1900).

Everywhere you look, the ashes are still glowing, and the air hangs heavy in the vaulted arches. Smoke still rises from smouldering wood and debris but it stays put between the walls, refuses to budge. Thirty-two blocks of houses burned down and little is left of the alleys between them but some brick facades, and even these are often reduced to ashes. Heaps of debris where wooden houses once stood. The inhabitants, whose property has gone up in smoke, are allowed onto the site. There is no moaning to be heard. Women pick about hopelessly for any remains of their belongings. The children play on the new hillocks of black refuse and finger the curiously deformed metal objects they find on them. A Turk sits cross-legged in front of a pall of smoke and fire, a blank stare on his face, and takes long puffs at his cigarette. Tobacco boxes and paper lie at his feet for the taking. His face is as sallow as a quince. Caffeine and nicotine have engraved crow’s feet around his eyes and wrinkles around his nose and mouth, as have the temptations of his wives. The blank stare, however, derives from his tribe and his religion. For him, fate is written in advance. It was recorded in the book of life long ago that the Tepe of Shkodra would be burnt to the ground on such-and-such a day and in such-and-such a year since the Hejira, on the day it fell into the hands of the infidels.

A lonely and spent fire extinguisher stands in a corner. All alone, it had tried to put out the conflagration. The smoke burns in our throats, the stench penetrates our nostrils and soot gets into our eyes. A charred dog bares its fangs… I must flee, get away from the place where nature proved that she was more powerful and could outdo the destructive nature of man.

A path leads me out of the stifling atmosphere to a Muslim cemetery, stones that remind me of the famous cemetery of the other Skutari, in Asia. Although the graveyard in Albanian Skutari [Shkodra] is smaller, it is by no means less chaotic. I plod through a forest of heliotrope blossoms - the irises that grow amidst the Turkish tombs and cover the engraved Suras.

The Customs Office in Shkodra, ca 1900.

The main street of town is lined with low houses battered by the artillery, many walls slumped or collapsing. Yes, these homes with their twisted window frames are still inhabited. Muck and excrement flow right in front of the houses, yet rose vines are creeping up staircases and I can smell the fragrance of the acacia trees. Under the leafy elms are coffeehouses. The hookahs on the tables are fitted with tubes turning the seated customers into a many-headed monster. The shops have no windows, only boards on which the proprietors and customers sit and chat. Most of them are tobacco shops. The merchants take their seats behind great mounds of brown tobacco, their only equipment being the scales that hang to one side. Bakeries display curious cakes and white bread baked by suspiciously dirty hands. Tinkers are at work and grocery men display figs, sheep cheese, dates, firewood, onions, corn and the petals of sumac trees that only grow here and that are used for tanning and darkening animal skins or are added to vinegar or to tobacco to give it greater aroma. Through the town run the tracks of a narrow-gauge railway, but the line is closed and the trains are long gone. A total of eight thousand five hundred artillery shells were fired at the town.

In the spacious courtyard formed by three long barracks and, on the other side of the street, the hospital that was still under construction, I catch a glimpse of the Montenegrin troops, row upon row, in prayers of thanksgiving. A thousand voices cry out “živeo” [long live!] and the men are then dismissed. The Turks and Albanians stand around, leaning on walls and observing the events, not without some astonishment.

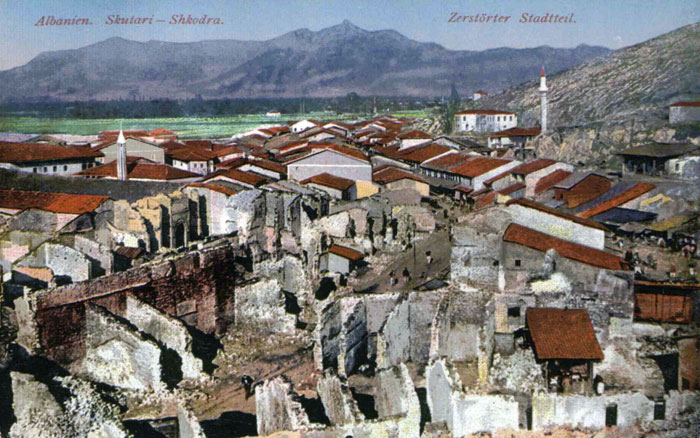

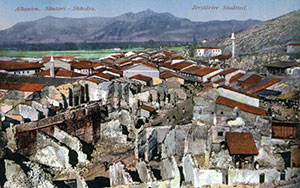

Colour postcard of Shkodra

showing the destruction of the old bazaar.Eight thousand Montenegrin soldiers are in Shkodra, most of them in brown and green field uniforms, but there are also many men in madder-red Dushankas with dark-blue linen trousers, and reservists sporting blue, red and white ribbons and carrying rifles. Patrols are out and about, on foot and on horseback, as are starving Turkish soldiers in moss-green tatters; Montenegrin officers with gold epaulettes, grey berets and the “grb,” the Montenegrin coat-of-arms; Turkish officers with sabres and tall fur caps; rich Albanian ladies in blouses of pink and silver and with gold-embroidered ribbons in their hair, wearing wide, flowery tunics and bloomers as big as a barrel; ladies from the harems garbed and veiled in black; Turkish peasant women in white linen trousers under a short skirt; Skipetars, Arnauts, Malessors, fair-skinned Ghegs and swarthy Tosks; men in white fustanellas, a pleated skirt, stockings made of tanned sheepskin, and shoes with turned-up toes; gypsies in rags and their women wrapped in carpet material. Colourful figures come to life everywhere as if in a geography book entitled “The Land of the Skipetars.” They parade and talk, speaking all the dialects there are from the Adriatic Sea to the Pindus Mountains, from Shkodra to the Gulf of Arta, but you can also hear Turkish, Greek, Serbian and Italian. For a gold coin you get change in all sorts of currencies: piasters, dinars, lire, crowns, etc.

There are two reputable hotels in Shkodra, but even in a third one I can find no accommodation. While I try to negotiate with the receptionist, the onetime Turkish police chief and mayor of Shkodra, Sulejman Bey, approaches and offers me a place to stay for the night. “Oh, je suis charmé, mon président!” “Vous me connaissez?” He had not noticed me at a banquet the previous evening with King Nikita in Cetinje or at least does not seem to recognise me. Now he seems awkwardly disappointed that the figure standing in front of him, to whom he has offered accommodation, is an acquaintance from the Konak. Why? And what is he doing here in this dingy joint anyway? (however this suspicion of mine arose later).

We go back to his villa on the outskirts of town, passing through streets in ruins. On our way, the agile, corpulent gentleman informs me that he had been taken to Cetinje under a Montenegrin escort three days after the town was taken, but was received quite heartily by the king. After swearing an oath of loyalty to him, he was allowed to participate in the court banquet and was then given permission to return to Shkodra. His villa was still occupied by the Montenegrins, but he had a little cottage in the garden that he was allowed to use, in which there were two beds. I ask him whether he is married. “Marié? Moi et marié? Non, monsieur, pas du tout!”

In the streets where he was once saluted with fear and respect, people now leer at him in disgust, in particular because he stands out in his flashy golden uniform. Suleiman Bey points to a coffeehouse where Montenegrin officers are sitting around drinking mocca. “Here is where we used to have coffee when we had a moment to spare. Now these swine occupy it the whole day.”

It is evident that he is suffering because the foe now reigns in what was once his sphere of command. “Mais, que faire? At the end, there were only eight Turkish battalions here. Constantinople abandoned us to our fate.”

We leave the town behind us and arrive at the villa surrounded by high walls. The little cottage in the garden is piled high with his possessions and junk – mostly pieces of furniture from the rooms of the villa. The chief of police tries to help me undress. Oh yes, fabled oriental courtesy, I think. And it is only with a decisive gesture that I manage to escape his kind attention. I am exhausted and lie down on the bed. But the chief of police, who has had the same tiring day behind him on the rocky roads of Montenegro and on the ship across Lake Shkodra, does not seem sleepy at all. He sits down on my bed and strokes my cheek and neck, which is certainly not a facet of oriental courtesy. Suddenly he gets up and goes to the door to see who is outside. “Of course, these Montenegrin officers,” he mutters, “they crash about like horses.”

He is about to lock the door, but I ask him to leave it open. I insist on this and take advantage of the moment to grasp for the Browning in my trousers in order to give proof of my determination to defend my honour. Suleiman Bey has understood and, with a shrug, leaves the key in the door lock. Frustrated, he lies down and goes to sleep.

He probably regrets having offered me a bed for the night.

So do I.

[Egon Erwin Kisch, Bombardement und Basarbrand von Skutari, from the volume Der rasende Reporter, Berlin 1925. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP