| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1914

Bajazid Elmaz Doda:

The Shepherds of Upper Reka (Macedonia)The Upper Reka Valley in western Macedonia, now devoid of inhabitants, was once home to extensive Albanian herding communities. The author of this text, Bajazid Elmaz Doda (ca. 1888-1933) from the now abandoned village of Shtirovica, was the private secretary and long-term companion of the Hungarian scholar and Albania expert, Baron Franz Nopcsa (1877-1933). Doda’s posthumously published book “Albanisches Bauernleben im Oberen Rekatal bei Dibra (Makedonien)” [Albanian Peasant Life in the Upper Reka Valley near Dibra (Macedonia)], written in 1914, offers a glimpse into the life of the Albanian shepherds who once drove their herds from the Sharr Mountains down to the Aegean coast and indeed to Asia Minor every winter.

Bajazid Elmaz Doda (ca. 1888-1933)

The Long March from Upper Reka to Winter Pastureland

When the shepherds of Upper Reka return from their 3-4 weeks of leave in the period between summer and winter, the qehaj [owner of the herds]counts the sheep in their presence and they set off southwards. If the flocks are simply to spend the winter months in the south, they are usually driven to Salonika, Serres or Drama. If they are to be sold off as meat on the occasion of Bayram in Constantinople, they journey without interruption right to the coast of Asia Minor, a full 800 kilometres! The trip to Salonika takes six weeks because of the slow progress of the animals, even they are on the move day and night. To get to Anatolia takes almost three months.

The route taken southwards follows the valley of the Vardar River down to Salonika and has been used for generations. The road to Serres and Drama passes through Üsküb [Skopje], Lake Kaplan (also called Blato Skupit), Štip, Radovište, Petrič und Demir Hisar. Asia Minor is reached from Drama via Kavalla, Djümurdjina [Komotini], Ipsala, Gallipoli and Panderma [Bandirma]. In Anatolia, the flocks are often left in the region of Muhaliç [Karacabey] in Bithynia. It is remarkable that the shepherds marching at the head of their flocks for 600 kilometres have no other means of finding their way than their memory. It must not fail them as the flocks move in the starlight along tracks that are hard to find. The Turkish Government has made it impossible for them to advance along proper roads because it has not built any. It is evident that the shepherd leading the flocks, in view of his great responsibility, has power and authority over all the other shepherds. As to the order of the advance, each large herd is accompanied by four shepherds, whose personal affairs are usually carried by two mules. When several flocks are on the move together, they are accompanied by a horse rider called a qehaja dhenet. He ensures that there are food and provisions for the shepherds. The herds do not approach larger towns when this can be avoided - Kavalla being the exception - because of the lack of fodder in the proximity thereof and, as such, the qehaja dhenet rides in advance and buys tobacco and food for the shepherds.

It is apparent that the shepherds moving in the night use every opportunity to enable their flocks to graze in the fields along the route. When the shepherd leading the herd quickens his pace, the animals stretch out in a line along the route, and when he slows his pace, they spread out sideways into the neighbouring fields and meadows. All that really needs to be done is for the lead shepherd to give a warning call to disturb the animals. If the bellwether co-operates, a clever shepherd can even convey the impression to onlookers that he is doing his very best to prevent the animals from grazing on other people’s property, although he is in fact doing exactly the opposite. One danger that the herds often encounter on their migration across the plain of Salonika are pits covered by grass that the local inhabitants of the region dig in the hope that one or two of the sheep will fall into them and go unnoticed.

A shepherd and his sheep in Bedyqas near Përmet

(Photo: Robert Elsie, March 2008)About four weeks after the shepherds leave Reka on their march southwards, the hergele (horsemen) set off. They are of course much quicker than the sheep and need only eight to ten days to get from Reka to Salonika. The owner of the herds who has been charged by his associates with leasing the winter pastureland arrives at the destination either with the hergele or, as often the case if he takes the train, before they get there.

The cost of winter pastureland, on which the herds of Reka spend almost half a year, is far greater than that of the mountain pastures. Prices ranging from 100 to 200 Turkish pounds (2200 to 400 Austrian crowns) are no rarity. These areas, as mentioned above, are the lowland regions along the Mediterranean coast.

When the herds reach their destination, the shepherds set about constructing a koliba [hut] for themselves on dry land with any material they can find. For the herds, they build a torla, also called an agole [sheep pen]. Both the koliba and torla are often made of rushes because the winter pastureland near Salonika is usually situated in marshy areas unsuitable for agriculture.

As to the koliba, it may be noted that it consists of two parts: a back room where all the personal effects of the shepherds - saddles, change of clothing, etc. are stored, and a front room used for cooking. The torla is constructed by ramming wooden poles into the earth and attaching long reeds (gjushma) to them to form a circular or cone-shaped wall. The uncovered portion of the torla is large enough for up to 500 sheep. If room is needed for more than 600 sheep, they build several torlas. The shepherds do not like to keep more than 500 sheep in one torla overnight because the animals churn the ground up and, if there is rain, it turns into a field of mud.

The herds graze in the daytime around Serres and Salonika. After sunset, throughout the winter months, they are driven back into the torlas. The shepherds have dinner in the koliba, consisting of bread, cheese, beans, or meat, etc. They then go out to the torla and sleep in strategic places where they think the flocks are most likely to be attacked by wolves, jackals or human beings. The odadži is responsible for guarding the koliba at night. If the qehaj has a reliable shepherd, he can safely leave the herds in winter pasture and return home. He returns to his herds later when the lambs are being born.

The shepherds of Reka are certainly no angels while in the south. One widespread trick that they use, even up to Hungary, is to lease pastureland that is far too small for their needs. This way, they have a legal right to settle in the midst of other fertile pastureland. The shepherds are given orders to have their flocks rest during the daytime. At night, the animals are all therefore the more active grazing in the surrounding meadows not leased to them. Many shepherds take advantage of such tricks and even though the sheep leave evident traces of their presence in the cornfields, it is impossible for the farmers to prove who is to blame because of the chaotic nature of the Turkish administration.

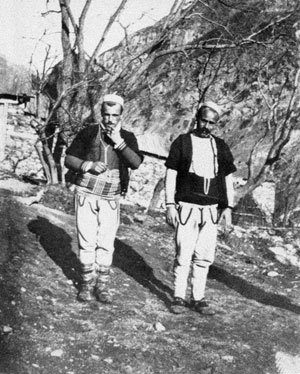

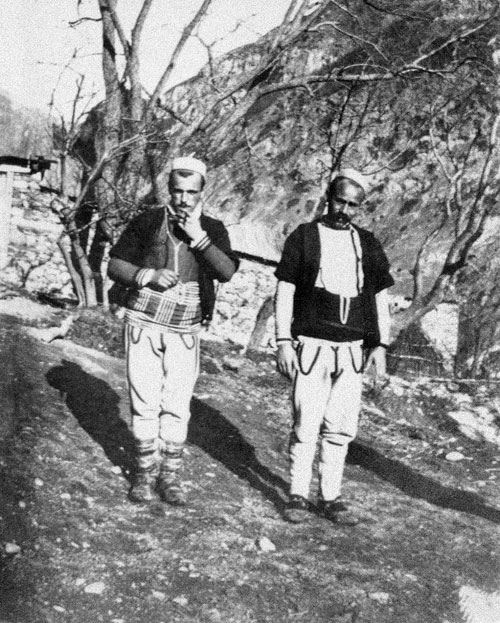

Two Muslims from Upper Reka

(Photo: Bajazid Elmaz Doda, 1907,

ÖNB/Vienna Bildarchiv NB902071B)

The tricks of the djokleme herders are even more extreme than those of the men who at least bother to lease a plot of pastureland. Djokleme grazing consists of moving the flocks about all the time – here and there, then a night spent somewhere else, and if anyone asks what the sheep are doing on a certain field, the shepherd replies, “I am taking them to the pasture down the road that I have leased.” The shepherds who use this trick and wander round and round all winter with their flocks need stamina, courage and determination. This is why the owners of the herds usually accompany the animals when they are djokleme grazing. The only time of year when the djokleme herders need to lease a plot of land of their own is when the lambs are being born in the spring. This period usually lasts two to three weeks if the sheep have all been covered at the same time and if no rams get in amongst them in the late summer.

We will cast a veil over the other mischievous deeds of the Albanians in Macedonia. Suffice it to say that the Albanian shepherds, armed like all Albanians, have an inclination for consuming beef although there are no cattle in their herds. This beef that they “come upon” is severed from the bone and boiled in its own grease on a low fire, constantly stirred. The whole stew is then poured into a skin bag where the grease solidified and the meat turns hard. It keeps a long time, and is called sesdorn.

Winter grazing can become very expensive for the herders if the weather turns bad or, as often happens, there is flooding. This hinders the animals from grazing and the herders are forced to buy fodder, hay etc.

After the birth of the lambs, the animals are all shorn. The sheep provide an average of two kilos of wool, called leshi gjat which is sold, mostly unwashed, primarily to butchers for two crowns a kilo. The young lambs that are left over are sold off for four to eight crowns. When this work is all done, the herders are obliged to pay a small livestock tax (dželep) of one crown per head to the Turkish authorities, and then the herds set off for the mountains. The tax receipt serves as a laissez-passer for the animals on their way back.

[excerpt from: Albanisches Bauernleben im Oberen Rekatal bei Dibra (Makedonien) von Bajazid Elmaz Doda, unter Mitwirkung von Franz Baron Nopcsa. Herausgegeben von Robert Elsie Balkanologische Beiträge zur Sprach- und Kulturwissenschaft. Volume 1 (Vienna: Lit-Verlag, 2007). Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP