| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

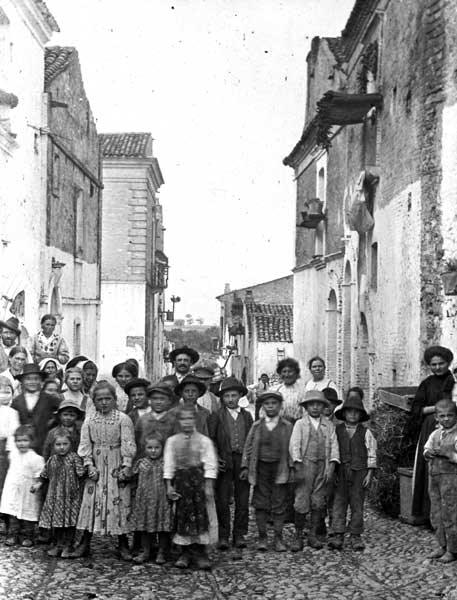

Children in an Italo-Albanian village (Photo: Max Lambertz 1913).

1915

Norman Douglas:

The Albanians of Old CalabriaNorman Douglas (1868-1952) was born in the Austrian village of Thüringen near Bludenz of an Austrian mother and Scottish father. He was educated in Scotland, England, Germany and France. A sexual scandal put an end to his career as a diplomat in 1896 and he emigrated to Italy, living in Naples and on the island of Capri. In 1912-1913 he worked in England for “The English Review,” through which he came into contact with writer D.H. Lawrence, but further sexual scandals cause him to return to exile in Italy and France. He died in Capri. Norman Douglas is the author of two highly successful travel books: “South Wind” (1911) and “Old Calabria” (1915), which, with their combination of erudition, wit and elegant literary style, are widely considered masterpieces of travel writing of the period. The latter book contains three chapters, given below, on the Albanian minority in the mountains of southern Italy.

Norman Douglas (1868-1952)

THE ‘GREEK’ SILA

It was to be the Sila in earnest, this time. I would traverse the whole country, from the Coscile valley to Catanzaro, at the other end.

Arriving from Cosenza the train deposited me, once more, at the unlovely station of Castrovillari. I looked around the dusty square, half-dazed by the sunlight - it was a glittering noon-day in July - but the postal waggon to Spezzano Albanese, my first resting-point, had not yet arrived. Then a withered old man, sitting on a vehicle behind the sorry skeleton of a horse, volunteered to take me there at once; we quickly came to terms; it was too hot, we both agreed, to waste breath in bar-gaining. With the end of his whip he pointed out the church of Spezzano on its hilltop; a proud structure it looked at this distance, though nearer acquaintance reduced it to extremely humble proportions.

The Albanian Spezzano (Spezzano Grande is another place) lies on the main road from Castrovillari to Cosenza, on the summit of a long-stretched tongue of limestone which separates the Crati river from the Esaro; this latter, after flowing into the Coscile, joins its waters with the Crati, and so closes the promontory. An odd geographical feature, this low stretch, viewed from the greater heights of Sila or Pollino; one feels inclined to take a broom and sweep it into the sea, so that the waters may mingle sooner.

Our road ascended the 1,000 feet in a sinuous ribbon of white dust, and an eternity seemed to pass as we crawled drowsily upwards to the music of the cicadas, under the simmering blue sky. There was not a soul in sight; a hush had fallen upon all things; great Pan was brooding over the earth. At last we entered the village, and here, once more, deathlike stillness reigned; it was the hour of post-prandial slumber.

At our knocking the proprietor of the inn, situated in a side-street, descended. But he was in a bad humour, and held out no hopes of refreshment. Certain doctors and government officials, he said, were gathered together in his house, telegraphically summoned to consult about a local case of cholera. As to edibles, the gentlemen had lunched, and nothing was left, absolutely nothing; it had been uno sterminio - an extermination - of all he possessed. The prospect of walking about the burning streets till evening did not appeal to me, and as this was the only inn at Spezzano I insisted, first gently, then forcibly - in vain. There was not so much as a chair to sit upon, he avowed; and therewith retired into his cool twilight.

Despairing, I entered a small shop wherein I had observed the only signs of life so far - an Albanian woman spinning in patriarchal fashion. It was a low-ceilinged room, stocked with candles, seeds, and other commodities which a humble householder might desire to purchase, including certain of those water-gugglets of Corigliano ware in whose shapely contours something of the artistic dreamings of old Sybaris still seems to linger. The proprietress, clothed in gaudily picturesque costume, greeted me with a smile and the easy familiarity which I have since discovered to be natural to all these women. She had a room, she said, where I could rest; there was also food, such as it was, cheese and wine, and -

‘Fruit?’ I inquired.

‘Ah, you like fruit? Well, we may not so much as speak about it just now - the cholera, the doctors, the policeman, the prison! I was going to say salami.’

Salami? I thanked her. I know Calabrian pigs and what they feed on, though it would be hard to describe in the language of polite society.

Despite the heat and the swarms of flies in that chamber, I felt little desire for repose after her simple repast; the dame was so affable and entertaining that we soon became great friends. I caused her some amusement by my efforts to understand and pronounce her language -these folk speak Albanian and Italian with equal facility - which seemed to my unpractised ears as hopeless as Finnish. Very patiently, she gave me a long lesson during which I thought to pick up a few words and phrases, but the upshot of it all was:

‘You’ll never learn it. You have begun a hundred years too late.’

I tried her with modern Greek, but among such fragments as remained on my tongue after a lapse of over twenty years, only hit upon one word that she could understand.

‘Quite right!’ she said encouragingly. ‘Why don’t you always speak properly? And now, let me hear a little of your own language.’

I gave utterance to a few verses of Shakespeare, which caused considerable merriment.

‘Do you mean to tell me,’ she asked, ‘that people really talk like that?’

‘Of course they do.’

‘And pretend to understand what it means?’

‘Why, naturally.’

‘Maybe they do,’ she agreed. ‘But only when they want to be thought funny by their friends.’

The afternoon drew on apace, and at last the pitiless sun sank to rest. I perambulated Spezzano in the gathering twilight; it was now fairly alive with people. An unclean place; an epidemic of cholera would work wonders here...

At 9.30 p.m. the venerable coachman presented himself, by appointment; he was to drive me slowly (out of respect for his horse) through the cool hours of the night as far as Vaccarizza, on the slopes of the Greek Sila, where he expected to arrive early in the morning. (And so he did; at half past five.) Not without more mirth was my leave-taking from the good shopwoman; something, apparently, was hopelessly wrong with the Albanian words of farewell which I had carefully memorized from our preceding lesson. She then pressed a paper parcel into my hand.

‘For the love of God,’ she whispered, ‘silence! Or we shall all be in jail tomorrow.’

It contained a dozen pears.

Driving along, I tried to enter into conversation with the coachman who, judging by his face, was a mine of local lore. But I had come too late; the poor old man was so weakened by age and infirmities that he cared little for talk, his thoughts dwelling, as I charitably imagined, on his wife and children, all dead and buried (so he said) many long years ago. He mentioned, however, the diluvio, the deluge, which I have heard spoken of by older people, among whom it is a fixed article of faith. This deluge is supposed to have affected the whole Crati valley, submerging towns and villages. In proof, they say that if you dig near Tarsia below the present river-level, you will pass through beds of silt and ooze to traces of old walls and cultivated land. Tarsia used to lie by the river-side, and was a flourishing place, according to the descriptions of Leandro Alberti and other early writers; floods and malaria have now forced it to climb the hills.

The current of the Crati is more spasmodic and destructive than in classical times when the river was ‘navigable’; and to one of its inundations may be due this legend of the deluge; to the same one, maybe, that affected the courses of this river and the Coscile, mingling their waters which used to flow separately into the Ionian. Or it may be a hazy memory of the artificial changing of the river-bed when the town of Sybaris, lying between these two rivers, was destroyed. Yet the streams are depicted as entering the sea apart in old maps such as those of Magini, Fiore, Coronelli, and Cluver; and the latter writes that ‘near the mouth of the Crati there flows into the same sea a river vulgarly called Cochile’. (1) This is important. It remains to be seen whether this statement is the result of a personal visit, or whether he simply repeated the old geography. His text in many places indicates a personal acquaintance with southern Italy - ‘Italiam,’ says Heinsius, ‘non semel peragravit’ - and he may well have been tempted to investigate a site like that of Sybaris. If so, the change in the river courses and possibly this ‘deluge’ has taken place since his day.

Deprived of converse, I relapsed into a doze, but soon woke up with a start. The carriage had stopped; it was nearly midnight; we were at Terranova di Sibari, whose houses were lit up by the silvery beams of the moon.

Thurii - death-place of Herodotus! How one would like to see this place by daylight. On the ancient site, which lies at a considerable distance, they have excavated antiquities, a large number of which are in the possession of the Marchese Galli at Castrovillari. I endeavoured to see his museum, but found it inaccessible for ‘family reasons’. The same answer was given me in regard to a valuable private library at Rossano, and annoying as it may be, one cannot severely blame such local gentlemen for keeping their collections to themselves. What have they to gain from the visits of inquisitive travellers?

During these meditations on my part, the old man hobbled busily to and fro with a bucket, bearing water from a fountain near at hand wherewith to splash the carriage-wheels. He persisted in this singular occupation for an unreasonably long time. Water was good for the wheels, he explained; it kept them cool.

At last we started, and I began to slumber once more. The carriage seemed to be going down a steep incline; endlessly it descended, with a pleasant swaying motion. Then an icy shiver roused me from my dreams. It was the Crati whose rapid waves, fraught with unhealthy chills, rippled brightly in the moonlight. We crossed the malarious valley, and once more touched the hills.

From these treeless slopes there streamed forth deliciously warm emanations stored up during the scorching hours of noon; the short scrub that clothed them was redolent of that peculiar Calabrian odour which haunts one like a melody - an odour of dried cistus and other aromatic plants, balsamic by day, almost overpowering at this hour. To aid and diversify the symphony of perfume, I lit a cigar, and then gave myself up to contemplation of the heavenly bodies. We passed a solitary man, walking swiftly with bowed head. What was he doing there?

‘Lupomanaro,’ said the driver.

A werewolf...

I had always hoped to meet with a werewolf on his nocturnal rambles, and now my wish was gratified. But it was disappointing to see him in human garb - even werewolves, it seems, must march with the times. This enigmatical growth of the human mind flourishes in Calabria, but is not popular as a subject of conversation. The more old-fashioned werewolves cling to the true versipellis habits, and in that case only the pigs, the inane Calabrian pigs, are dowered with the faculty of distinguishing them in daytime, when they look like any other ‘Christian’. There is a record, in Fiore’s book, of an epidemic of lycanthropy that attacked the boys of Cassano. (Why only the boys?) It began on 31 July 1210; and the season of the year strikes me as significant.

After that I fell asleep in good earnest, nor did I wake up again till the sun was peering over the eastern hills. We were climbing up a long slope; the Albanian settlements of Vaccarizza and San Giorgio lay before us and, looking back, I still saw Spezzano on its ridge; it seemed so close that a gunshot could have reached it.

These non-Italian villages date from the centuries that followed the death of Scanderbeg, when the Grand Signior consolidated his power. The refugees arrived in flocks from over the sea, and were granted tracts of wild land whereon to settle - some of them on this incline of the Sila, which was accordingly called ‘Greek’ Sila, the native confusing these foreigners with the Byzantines whose dwellings, as regards Calabria, are now almost exclusively confined to the distant region of Aspromonte. Colonies of Albanians are scattered all over South Italy, chiefly in Apulia, Calabria, Basilicata, and Sicily; a few are in the north and centre - there is one on the Po, for instance, now reduced to 200 inhabitants; most of these latter have become absorbed into the surrounding Italian element. Angelo Masci (reprinted 1846) says there are 59 villages of them, containing altogether 83,000 inhabitants - exclusive of Sicily; Morelli (1842) gives their total population for Italy and Sicily at 103,466. If these figures are correct, the race must have multiplied latterly, for I am told there are now some 200,000 Albanians in the kingdom, living in about 80 villages. This gives approximately 2,500 for each settlement - a likely number, if it includes those who are at present emigrants in America.

There is a voluminous literature on the subject of these strangers, the authors of which are nearly all Albanians themselves. The fullest account of older conditions may well be that contained in the third volume of Rodotà’s learned work (1758); the ponderous Francesco Tajani (1886) brings affairs up to date, or nearly so. If only he had provided his book with an index!

There were troubles at first. Arriving, as they did, solely ‘with their shirts and rhapsodies’ (so one of them described it to me) - that is, despoiled of everything, they indulged in robberies and depredations somewhat too freely even for those free days, with the result that ferocious edicts were issued against them, and whole clans wiped out. It was a case of necessity knowing no law. But in proportion as the forests were hewn down and crops sown, they became as respectable as their hosts. They are bilingual from birth, one might almost say, and numbers of the men also express themselves correctly in English, which they pick up in the United States.

These islands of alien culture have been hotbeds of Liberalism throughout history. The Bourbons persecuted them savagely on that account, exiling and hanging the people by scores. At this moment there is a good deal of excitement going on in favour of the Albanian revolt beyond the Adriatic, and it was proposed, among other things, to organize a demonstration in Rome, where certain Roman ladies were to dress themselves in Albanian costumes and thus work upon the sentiments of the nation; but ‘the authorities’ forbade this and every other movement. None the less, there has been a good deal of clandestine recruiting, and bitter recriminations against this turcophile attitude on the part of Italy - this ‘reactionary rigorism against every manifestation of sympathy for the Albanian cause’. Patriotic pamphleteers ask, rightly enough, why difficulties should be placed in the way of recruiting for Albania, when, in the recent cases of Cuba and Greece, the despatch of volunteers was actually encouraged by the government? ‘Legality has ceased to exist here; we Albanians are watched and suspected exactly as our compatriots now are by the Turks... They sequestrate our manifestos, they forbid meetings and conferences, they pry into our postal correspondence... Civil and military authorities have conspired to prevent a single voice of help and comfort reaching our brothers, who call to us from over the sea.’ A hard case, indeed. But Vienna and Cettinje might be able to throw some light upon it. (2)

The Albanian women, here as elsewhere, are the veriest beasts of burden; unlike the Italians, they carry everything (babies, and wood, and water) on their backs. Their crudely tinted costumes would be called more strange than beautiful under any but a bright sunshiny sky. The fine native dresses of the men have disappeared long ago; they even adopted, in past days, the high-peaked Calabrian hat which is now only worn by the older generation. Genuine Calabrians often settle in these foreign villages, in order to profit by their anti-feudal institutions. For even now the Italian cultivator is supposed to make, and actually does make ‘voluntary’ presents to his landlord at certain seasons; gifts which are always a source of irritation and, in bad years, a real hardship. The Albanians opposed themselves from the very beginning against these medieval practices. ‘They do not build houses,’ says an old writer, ‘so as not to be subject to barons, dukes. princes, or other lords. And if the owner of the land they inhabit ill-treats them, they set fire to their huts and go elsewhere.’ An admirable system, even nowadays.

One would like to be here at Easter time to see the rusalet - those Pyrrhic dances where the young men group themselves in martial array, and pass through the streets with song and chorus, since, soon enough, America will have put an end to such customs. The old Albanian guitar of nine strings has already died out, and the double tibia - biforem dat tibia cantum - will presently follow suit. This instrument, familiar from classical sculpture and lore, and still used in Sicily and Sardinia, was once a favourite with the Sila shepherds, who called it ‘fischietto a pariglia’. But some years ago I vainly sought it in the central Sila; the answer to my inquiries was everywhere the same: they knew it quite well; so and so used to play it; certain persons in certain villages still made it - they described it accurately enough, but could not produce a specimen. Single pipes, yes; and bagpipes galore; but the tibiae pares were ‘out of fashion’ wherever I asked for them.

Here, in the Greek Sila, I was more fortunate. A boy at the village of Macchia possessed a pair which he obligingly gave me, after first playing a song - a farewell song - a plaintive ditty that required, none the less, an excellent pair of lungs, on account of the two mouthpieces. Melodies on this double flageolet are played principally at Christmas time. The two reeds are about twenty-five centimetres in length, and made of hollow cane; in my specimen, the left hand controls four, the other six holes; the Albanian name of the instrument is ‘fiscarol’.

From a gentleman at Vaccarizza I received a still more valuable present - two neolithic celts (aeneolithic, I should be inclined to call them) wrought in close-grained quartzite, and found not far from that village. These implements must be rare in the uplands of Calabria, as I have never come across them before, though they have been found, to my knowledge, at Savelli in the central Sila. At Vaccarizza they call such relics ‘pic’ - they are supposed, as usual, to be thunderbolts, and I am also told that a piece of string tied to one of them cannot be burnt in fire. The experiment might be worth trying.

Meanwhile, the day passed pleasantly at Vaccarizza. I became the guest of a prosperous resident, and was treated to genuine Albanian hospitality and excellent cheer. I only wish that all his compatriots might enjoy one meal of this kind in their lifetime. For they are poor, and their homes of miserable aspect. Like all too many villages in South Italy, this one is depopulated of its male inhabitants, and otherwise dirty and neglected. The impression one gains on first seeing one of these places is more than that of Oriental decay; they are not merely ragged at the edges. It is a deliberate and sinister chaos, a note of downright anarchy - a contempt for those simple forms of refinement which even the poorest can afford. Such persons, one thinks, cannot have much sense of home and its hallowed associations; they seem to be everlastingly ready to break with the existing state of things. How different from England, where the humblest cottages, the roadways, the very stones testify to immemorial love of order, to neighbourly feelings and usages sanctioned by time!

They lack the sense of home as a fixed and old-established topographical point; as do the Arabs and Russians, neither of whom have a word expressing our ‘home’ or ‘Heimat’. Here, the nearest equivalent is la famiglia. We think of a particular house or village where we were born and where we spent our impressionable days of childhood; these others regard home not as a geographical but as a social centre, liable to shift from place to place; they are at home everywhere, so long as their clan is about them. That acquisitive sense which affectionately adorns our meanest dwelling, slowly saturating it with memories, has been crushed out of them - if it ever existed - by hard blows of fortune; it is safer, they think, to transform the labour of their hands into gold, which can be moved from place to place or hidden from the tyrant’s eye. They have none of our sentimentality in regard to inanimate objects. Eliza Cook’s feelings towards her ‘old arm-chair’ would strike them as savouring of childishness. Hence the unfinished look of their houses, within and without. Why expend thought and wealth upon that which may be abandoned tomorrow?

The two churches of Vaccarizza, dark and unclean structures, stand side by side, and I was shown through them by their respective priests, Greek and Catholic, who walked arm in arm in friendly wise, and meekly smiled at a running fire of sarcastic observations on the part of another citizen directed against the bottega in general - the ‘shop’, as the church is sometimes irreverently called. The Greco-Catholic cult to which these Albanians belong is a compromise between the Orthodox and Roman; their priests may wear beards and marry wives, they use bread instead of the wafer for sacramental purposes, and there are one or two other little differences of grave import.

Six Albanian settlements lie on these northern slopes of the Sila - San Giorgio, Vaccarizza, San Cosimo, Macchia, San Demetrio Corone, and Santa Sofia d’Epiro. San Demetrio is the largest of them, and thither, after an undisturbed night’s rest at the house of my kind host - the last, I fear, for many days to come - I drove in the sunlit hours of next morning. Along the road one can see how thoroughly the Albanians have done their work; the land is all under cultivation, save for a dark belt of trees overhead, to remind one of what once it was. Perhaps they have eradicated the forest over-zealously, for I observe in San Demetrio that the best drinking water has now to be fetched from a spring at a considerable distance from the village; it is unlikely that this should have been the original condition of affairs; deforestation has probably diminished the water-supply.

It was exhilarating to traverse these middle heights with their aerial views over the Ionian and down olive-covered hill-sides towards the wide valley of the Crati and the lofty Pollino range, now swimming in mid-summer haze. The road winds in and out of gullies where rivulets descend from the mountains; they are clothed in cork-oak, ilex, and other trees; golden orioles, jays, hoopoes, and rollers flash among the foliage. In winter these hills are swept by boreal blasts from the Apennines, but at this season it is a delightful tract of land.ALBANIANS AND THEIR COLLEGE

San Demetrio, famous for its Italo-Albanian College, lies on a fertile incline sprinkled with olives and mulberries and chestnuts, 1,500 feet above sea-level. They tell me that within the memory of living man no Englishman has ever entered the town. This is quite possible; I have not yet encountered a single English traveller, during my frequent wanderings over south Italy. Gone are the days of Keppel Craven and Swinburne, of Eustace and Brydone and Hoare! You will come across sporadic Germans immersed in Hohenstaufen records, or searching after Roman antiquities, butterflies, minerals, or landscapes to paint - you will meet them in the most unexpected places; but never an Englishman. The adventurous type of Anglo-Saxon probably thinks the country too tame; scholars, too trite; ordinary tourists, too dirty.

The accommodation and food in San Demetrio leave much to be desired; its streets are irregular lanes, ill-paved with cobbles of gneiss and smothered under dust and refuse. None the less, what noble names have been given to these alleys - names calculated to fire the ardent imagination of young Albanian students, and prompt them to valorous and patriotic deeds! Here are the streets of ‘Odysseus’, of ‘Salamis’ and ‘Marathon’ and ‘Thermopylae’, telling of the glory that was Greece; ‘Via Skanderbeg’ and ‘Hypsilanti’ awaken memories of more immediate renown; ‘Corso Dante Alighieri’ reminds them that their Italian hosts, too, have done something in their day; the ‘Piazza Francesco Ferrer’ causes their ultra-liberal breasts to swell with mingled pride and indignation; while the ‘Via dell’Industria’ hints, not obscurely, at the great truth that genius, without a capacity for taking pains, is an idle phrase. Such appellations, without a doubt, are stimulating and glamorous. But if the streets themselves have seen a scavenger’s broom within the last half-century, I am much mistaken. The goddess ‘Hygeia’ does not figure among their names, nor yet that Byzantine Monarch whose infantile exploit might be re-enacted in ripest maturity without attracting any attention in San Demetrio. To the pure all things are pure.

The town is exclusively Albanian; the Roman Catholic church has fallen into disrepair, and is now used as a shed for timber. But at the door of the Albanian sanctuary I was fortunate enough to intercept a native wedding, just as the procession was about to enter the portal. Despite the fact that the bride was considered the ugliest girl in the place, she had been duly ‘robbed’ by her bold or possibly blind lover - her features were providentially veiled beneath her nuptial flammeum, and of her squat figure little could be discerned under the gorgeous accoutrements of the occasion. She was ablaze with ornaments and embroidery of gold, on neck and shoulders and wrist; a wide lace collar fell over a bodice of purple silk; silken too, and of brightest green, was her pleated skirt. The priest seemed ineffably bored with his task, and mumbled through one or two pages of holy books in record time; there were holdings of candles, interchanging of rings, sacraments of bread and wine and other solemn ceremonies - the most quaint being the stephanoma, or crowning, of the happy pair, and the moving of their respective crowns from the head of one to that of the other. It ended with a chanting perlustration of the church, led by the priest: this is the so-called ‘pesatura’.

Albanian costume

from Mongrassano.I endeavoured to attune my mind to the gravity of this marriage, to the deep historico-ethnological-poetical significance of its smallest detail. Such rites, I said to myself, must be understood to be appreciated, and had I not been reading certain native commentators on the subject that very morning? Nevertheless, my attention was diverted from the main issue - the bridegroom’s face had fascinated me. The self-conscious male is always at a disadvantage during grotesquely splendid buffooneries of this kind; and never, in all my life, have I seen a man looking such a sorry fool as this individual, never; especially during the perambulation, when his absurd crown was supported on his head, from behind, by the hand of his best man.

Meanwhile a handful of boys, who seemed to share my private feelings in regard to the performance, had entered the sacred precincts, their pockets stuffed with living cicadas. These Albanian youngsters, like all true connoisseurs, are aware of the idiosyncrasy of the classical insect which, when pinched or tickled on a certain spot, emits its characteristic and ear-piercing note - the ‘lily-soft voice’ of the Greek bard. The cicadas, therefore, were duly pinched and then let loose; like squibs and rockets they careered among the congregation, dashing in our faces and clinging to our garments; the church resounded like an olive-copse at noon. A hot little hand conveyed one of these tremulously throbbing creatures into my own, and obeying a whispered injunction of ‘Let it fly, sir!’ I had the joy of seeing the beast alight with a violent buzz on the head of the bride - doubtless the happiest of auguries. Such conduct, on the part of English boys, would be deemed very naughty and almost irreverent; but here, one hopes, it may have its origin in some obscure but pious credence such as that which prompts the populace to liberate birds in churches, at Easter time. These escaping cicadas, it may be, are symbolical of matrimony - the individual man and woman freed, at last, from the dungeon-like horrors of celibate existence; or, if that parallel be far-fetched, we may conjecture that their liberation represents that afflatus of the human soul, aspiring upwards to merge its essence into the Divine All… (3)

The pride of San Demetrio is its college. You may read about it in Professor Mazziotti’s monograph; but whoever wishes to go to the fountain-head must peruse the Historia erectionis pontifici collegi Corsini ullanensis, etc., of old Zavarroni - an all-too-solid piece of work. Founded under the auspices of Pope Clement XII in 1733 (or 1735) at San Benedetto Ullano, it was moved hither in 1794, and between that time and now has passed through fierce vicissitudes. Its president, Bishop Bulgliari, was murdered by the brigands in 1806; much of its lands and revenues have been dissipated by maladministration; it was persecuted for its Liberalism by the Bourbons, who called it a ‘workshop of the devil.’ It distinguished itself during the anti-dynastic revolts of 1799 and 1848 and, in 1860, was presented with 12,000 ducats by Garibaldi, ‘in consideration of the signal services rendered to the national cause by the brave and generous Albanians.’ (4) Even now the institution is honeycombed with Freemasonry - the surest path to advancement in any career, in modern Italy. Times indeed have changed since the ‘Inviolable Constitutions’ laid it down that ‘nullus omnino Alumnus in Collegio detineatur, cuius futurae Christianae pietatis significato non extet’. But only since 1900 has it been placed on a really sound and prosperous footing. An agricultural school has lately been added, under the supervision of a trained expert. They who are qualified to judge speak of the college as a beacon of learning - an institution whose aims and results are alike deserving of high respect. And certainly it can boast of a fine list of prominent men who have issued from its walls.

This little island of stern mental culture contains, besides 25 teachers and as many servants, some 300 scholars preparing for a variety of secular professions. About 50 of them are Italo-Albanians, 10 or thereabouts are genuine Albanians from over the water, the rest Italians, among them two dozen of those unhappy orphans from Reggio and Messina who flooded the country after the earthquake, and were ‘dumped down’ in colleges and private houses all over Italy. Some of the boys come of wealthy families in distant parts, their parents surmising that San Demetrio offers no temptations to youthful folly and extravagance. In this, so far as I can judge, they are perfectly correct.

The heat of summer and the fact that the boys were in the throes of their examinations may have helped to make the majority of them seem pale and thin; they certainly complained of their food, and the cook was the only prosperous-looking person whom I could discover in the establishment - his percentages, one suspects, being considerable. The average yearly payment of each scholar for board and tuition is only twenty pounds (it used to be twenty ducats); how shall superfluities be included in the bill of fare for such a sum?

The class-rooms are modernized; the dormitories neither clean nor very dirty; there is a rather scanty gymnasium as well as a physical laboratory and museum of natural history. Among the recent acquisitions of the latter is a vulture (gyps fulvus) which was shot here in the spring of this year. The bird, they told me, has never been seen in these regions before; it may have come over from the east, or from Sardinia, where it still breeds. I ventured to suggest that they should lose no time in securing a native porcupine, an interesting beast concerning which I never fail to inquire on my rambles. They used to be encountered in the Crati valley; two were shot near Corigliano a few years ago, and another not far from Cotronei on the Neto; they still occur in the forests near the ‘Pagiarelle’ above Petilia Policastro; but, judging by all indications, I should say that this animal is rapidly approaching extinction not only here, but all over Italy. Another very rare creature, the otter, was killed lately at Vaccarizza, but unfortunately not preserved.

Fencing and music are taught, but those athletic exercises which led to the victories of Marathon and Salamis are not much in vogue - mens sana in corpore sano is clearly not the ideal of the place; fighting among the boys is reprobated as ‘savagery’, and corporal punishment forbidden. There is no playground or workshop, and their sole exercise consists in dull promenades along the high road under the supervision of one or more teachers, during which the youngsters indulge in attempts at games by the wayside which are truly pathetic. So the old ‘Inviolable Constitutions’ ordain that ‘the scholars must not play outside the college, and if they meet any one, they should lower their voices’. A rule of recent introduction is that in this warm weather they must all lie down to sleep for two hours after the midday meal; it may suit the managers, but the boys consider it a great hardship and would prefer being allowed to play. Altogether, whatever the intellectual results may be, the moral tendency of such an upbringing is damaging to the spirit of youth and must make for precocious frivolity and brutality. But the pedagogues of Italy are like her legislators: theorists. They close their eyes to the cardinal principles of all education - that the waste products and toxins of the imagination are best eliminated by motor activities, and that the immature stage of human development, far from being artificially shortened, should be prolonged by every possible means.

If the internal arrangement of this institution is not all it might be as regards the healthy development of youth, the situation of the college resembles the venerable structures of Oxford in that it is too good, far too good, for mere youngsters. This building, in its seclusion from the world, its pastoral surroundings and soul-inspiring panorama, is an abode not for boys but for philosophers; a place to fill with a wave of deep content the sage who has outgrown earthly ambitions. Your eye embraces the snow-clad heights of Dolcedorme and the Ionian Sea, wandering over forests, and villages, and rivers, and long reaches of fertile country; but it is not the variety of the scene, nor yet the historical memories of old Sybaris which kindle the imagination so much as the spacious amplitude of the whole prospect. In England we think something of a view of ten miles. Conceive, here, a grandiose valley wider than from Dover to Calais, filled with an atmosphere of such impeccable clarity that there are moments when one thinks to see every stone and every bush on the mountains yonder, thirty miles distant. And the cloud-effects, towards sunset, are such as would inspire the brush of Turner or Claude Lorraine...

For the college, as befits its grave academic character, stands by itself among fruitful fields and backed by a chestnut wood, at ten minutes’ walk from the crowded streets. It is an imposing edifice - the Basilean convent of St Adrian, with copious modern additions; the founders may well have selected this particular site on account of its fountain of fresh water, which flows on as in days of yore. One thinks of those communities of monks in the Middle Ages, scattered over this wild region and holding rare converse with one another by gloomy forest paths - how remote their life and ideals! In the days of Fiore (1691) the inmates of this convent still practised their old rites.

The nucleus of the building is the old chapel, containing a remarkable font; two antique columns sawn up (apparently for purposes of transportation from some pagan temple by the shore) - one of them being of African marble and the other of grey granite; there is also a tessellated pavement with beast-patterns of leopards and serpents akin to those of Patir. Bertaux gives a reproduction of this serpent; he assimilates it, as regards technique and age, to that which lies before the altar of Monte Cassino and was wrought by Greek artisans of the abbot Desiderus. The church itself is held to be two centuries older than that of Patir.

The library, once celebrated, contains musty folios of classics and their commentators, but nothing of value. It has been ransacked of its treasures like that of Patir, whose disjecta membra have been tracked down by the patience and acumen of Monsignor Batiffol.

Batiffol, Bertaux - Charles Diehl, Jules Gay (who has also written on San Demetrio) - Huillard-Bréholles - Luynes - Lenormant ... here are a few French scholars who have recently studied these regions and their history. What have we English done in this direction?

Nothing. Absolutely nothing.

Such thoughts occur inevitably.

It may be insinuated that researches of this kind are gleanings; that our English genius lies rather in the spade-work of pioneers like Leake or Layard. Granted. But a hard fact remains; the fact, namely, that could any of our scholars have been capable of writing in the large and profound manner of Bertaux or Gay, not one of our publishers would have undertaken to print his work. Not one. They know their business; they know that such a book would have been a dead loss. Therefore let us frankly confess the truth: for things of the mind there is a smaller market in England than in France. How much smaller only they can tell, who have familiarized themselves with other departments of French thought.

Here, then, I have lived for the past few days, strolling among the fields, and attempting to shape some picture of these Albanians from their habits and such of their literature as has been placed at my disposal. So far, my impression of them has not changed since the days when I used to rest at their villages, in Greece. They remind me of the Irish. Both races are scattered over the earth and seem to prosper best outside their native country; they have the same songs and bards, the same hero-chieftains, the same combativeness and frank hospitality; both are sunk in bigotry and broils; they resemble one another in their love of dirt, disorder, and display, in their enthusiastic and adventurous spirit, their versatile brilliance of mind, their incapacity for self-government and general (Celtic) note of inspired inefficiency. And both profess a frenzied allegiance to an obsolete tongue which, were it really cultivated as they wish, would put a barrier of triple brass between themselves and the rest of humanity.

Even as the Irish despise the English as their worldly and effete relatives, so the Albanians look down upon the Greeks - even those of Pericles - with profoundest contempt. The Albanians, so says one of their writers, are ‘the oldest people upon earth’, and their language is the ‘divine Pelasgic mother-tongue’. I grew interested awhile in Stanislao Marchianò’s plausibly entrancing study on this language, as well as in a pamphlet of de Rada’s on the same subject; but my ardour has cooled since learning, from another native grammarian, that these writers are hopelessly in the wrong on nearly every point. So much is certain, that the Albanian language already possesses more than thirty different alphabets (each of them with nearly fifty letters). Nevertheless they have not yet, in these last four (or forty) thousand years, made up their minds which of them to adopt, or whether it would not be wisest, after all, to elaborate yet another one - a thirty-first. And so difficult is their language with any of these alphabets that even after a five days’ residence on the spot I still find myself puzzled by such simple passages as this:

... Zilji,

mosse vet, ce asso mbremie

te ngcriret me iljiζ, praa

gjiθ e miegculem, mbi ζiaarr

rriij i sgjuat. Nje voogh e keljbur

ζorrevet te ljosta

ndjej se i oχtenej

e pisseroghej. Zuu shiu

menes; ne mee se ljinaar

chish ljeen pa-shuatur

sχiotta, e i ducheje per moon.I will only add that the translation of such a passage - it contains twenty-eight accents which I have omitted - is mere child’s play to its pronunciation.

AN ALBANIAN SEER

Sometimes I find my way to the village of Macchia, distant about three miles from San Demetrio. It is a dilapidated but picturesque cluster of houses, situated on a projecting tongue of land which is terminated by a little chapel to Saint Elias, the old sun-god Helios, (5) lover of peaks and promontories, whom in his Christian shape the rude Albanian colonists brought hither from their fatherland, even as, centuries before, he had accompanied the Byzantines on the same voyage and, fifteen centuries yet earlier, the Greeks.

At Macchia, was born, in 1814, of an old and relatively wealthy family, Girolamo de Rada, (6) a flame-like patriot in whom the tempestuous aspirations of modern Albania took shape. The ideal pursued during his long life was the regeneration of his country; and if the attention of international congresses and linguists and folklorists is now drawn to this little corner of the earth - if, in 1902, twenty-one newspapers were devoted to the Albanian cause (eighteen in Italy alone, and one even in London) - it was wholly his merit.

He was the son of a Greco-Catholic priest. After a stern religious upbringing under the paternal roof of Macchia and in the college of San Demetrio, he was sent to Naples to complete his education. It is characteristic of the man that even in the hey-day of youth he cared little for modern literature and speculations and all that makes for exact knowledge, and that he fled from his Latin teacher, the celebrated Puoti, on account of his somewhat exclusive love of grammatical rules. None the less, though congenitally averse to the materialistic and subversive theories that were then seething in Naples, he became entangled in the anti-Bourbon movements of the late thirties, and narrowly avoided the death-penalty which struck down some of his comrades. At other times his natural piety laid him open to the accusation of reactionary monarchical leanings.

He attributed his escape from this and every other peril to the hand of God. Throughout life he was a zealous reader of the Bible, a firm and even ascetic believer, forever preoccupied, in childlike simplicity of soul, with first causes. His spirit moved majestically in a world of fervent platitudes. The whole Cosmos lay serenely distended before his mental vision; a benevolent God overhead, devising plans for the prosperity of Albania; a malignant, ubiquitous, and very real devil, thwarting these His good intentions whenever possible; mankind on earth, sowing and reaping in the sweat of their brow, as was ordained of old. Like many poets, he never disabused his mind of this comfortable form of anthropomorphism. He was a firm believer, too, in dreams. But his guiding motive, his sun by day and star by night, was a belief in the ‘mission’ of the Pelasgian race now scattered about the shores of the Inland Sea - in Italy, Sicily, Greece, Dalmatia, Romania, Asia Minor, Egypt - a belief as ardent and irresponsible as that which animates the ‘Lost Tribe’ enthusiasts of England. He considered that the world hardly realized how much it owed to his country-folk; according to his views, Achilles, Philip of Macedon, Alexander the Great, Aristotle, Pyrrhus, Diocletian, Julian the Apostate - they were all Albanians. Yet even towards the end of his life he is obliged to confess:

But the evil demon who for over four thousand years has been hindering the Pelasgian race from collecting itself into one state, is still endeavouring by insidious means to thwart the work which would lead it to that union.

Disgusted with the clamorous and intriguing bustle of Naples, he retired, at the early age of thirty-four, to his natal village of Macchia, throwing over one or two offers of lucrative worldly appointments. He describes himself as wholly disenchanted with the ‘facile fatuity’ of Liberalism, the fact being that he lacked what a French psychologist has called the ‘function of the real’; his temperament was not of the kind to cope with actualities. This retirement is an epoch in his life - it is the Grand Renunciation. Henceforward he loses personal touch with thinking humanity. At Macchia he remained, brooding on Albanian wrongs, devising remedies, corresponding with foreigners, and writing - ever writing; consuming his patrimony in the cause of Albania, till the direst poverty dogged his footsteps.

I have read some of his Italian works. They are curiously oracular, like the whisperings of those fabled Dodonian oaks of his fatherland; they heave with a darkly-virile mysticism. He shares Blake’s ruggedness, his torrential and confused utterance, his benevolence, his flashes of luminous inspiration, his moral background. He resembles that visionary in another aspect: he was a consistent and passionate adorer of the Ewig-weibliche. Some of the female characters in his poems retain their dewy freshness, their exquisite originality, even after passing through the translator’s crucible.

At the age of nineteen he wrote a poem on ‘Odysseus’, which was published under a pseudonym. Then, three years later, there appeared a collection of rhapsodies entitled Milosao, which he had garnered from the lips of Albanian village maidens. It is his best-known work, and has been translated into Italian more than once. After his return to Macchia followed some years of apparent sterility, but later on, and especially during the last twenty years of his life, his literary activity became prodigious. Journalism, folklore, poetry, history, grammar, philology, ethnology, aesthetics, politics, morals - nothing came amiss to his gifted pen, and he was fruitful, say his admirers, even in his errors. Like other men inflamed with one single idea, he boldly ventured into domains of thought where specialists fear to tread. His biographer enumerates forty-three different works from his pen. They all throb with a resonant note of patriotism; they are ‘fragments of a heart’, and indeed, it has been said of him that he utilized even the grave science of grammar as a battlefield whereon to defy the enemies of Albania. But perhaps he worked most successfully as a journalist. His Fiamuri Arberit (the ‘Banner of Albania’) became the rallying of his countrymen in every corner of the earth.

These multifarious writings - and doubtless the novelty of his central theme - attracted the notice of German philologers and linguists, of all lovers of freedom, folklore, and verse. Leading Italian writers like Cantù praised him highly; Lamartine, in 1844, wrote to him: ‘Je suis bien-heureux de ce signe de fraternité poétique et politique entre vous et moi. La poésie est venue de vos rivages et doit y retourner. ..’ Hermann Buchholtz discovers scenic changes worthy of Shakespeare, and passages of Aeschylean grandeur, in his tragedy Sofonisba. Camet compares him with Dante, and the omniscient Mr Gladstone wrote in 1880 - a post-card, presumably - belauding his disinterested efforts on behalf of his country. He was made the subject of many articles and pamphlets, and with reason. Up to his time, Albania had been a myth. He it was who divined the relationship between the Albanian and Pelasgian tongues; who created the literary language of his country, and formulated its political ambitions.

Whereas the hazy Autobiologia records complicated political intrigues at Naples that are not connected with his chief strivings, the little Testamente politico, printed towards the end of his life, is more interesting. It enunciates his favourite and rather surprising theory that the Albanians cannot look for help and sympathy save only to their brothers, the Turks. Unlike many Albanians on either side of the Adriatic, he was a pronounced Turcophile, detesting the ‘stolid perfidy’ and ‘arrogant disloyalty’ of the Greeks. Of Austria, the most insidious enemy of his country’s freedom, he seems to have thought well. A year before his death he wrote to an Italian translator of Milosao (I will leave the passage in the original, to show his cloudy language):

Ed un tempo propizio la accompagna: la recostituzione dell’Epiro nei suoi quattro vilayet autonomi quale e nei propri consigli e nei propri desideri; ricostituzione, che pel suo Giorale, quello dell’ottimo A. Lorecchio - cui precede il principe Nazionale Kastriota, Chini - si annuncia fatale, e quasi fulcro della stabilità dello impero Ottomano, a della pace Europea; preludio di quella diffusione del regno di Dio sulla terra, che sarà la Pace tra gli Uomini.

Truly a remarkable utterance, and one that illustrates the disadvantages of living at a distance from the centres of thought. Had he travelled less with the spirit and more with the body, his opinions might have been modified and corrected. But he did not even visit the Albanian colonies in Italy and Sicily. Hence that vast confidence in his mission - a confidence born of solitude, intellectual and geographical. Hence that ultra-terrestrial yearning which tinges his apparently practical aspirations.

Girolamo De Rada (1814-1903)He remained at home, ever poor and industrious; wrapped in bland exaltation and oblivious to contemporary movements of the human mind. Not that his existence was without external activities. A chair of Albanian literature at San Demetrio, instituted in 1849 but suppressed after three years, was conferred on him in 1892 by the historian and minister Pasquale Villari; for a considerable time, too, he was director of the communal school at Corigliano, where, with characteristic energy, he set up a printing press; violent journalistic campaigns succeeded one another; in 1896 he arranged for the first congress of Albanian language in that town, which brought together delegates from every part of Italy and elicited a warm telegram of felicitation from the minister Francesco Crispi, himself an Albanian. Again, in 1899, we find him reading a paper before the twelfth international congress of Orientalists at Rome.

But best of all, he loved the seclusion of Macchia.

Griefs clustered thickly about the closing years of this unworldly dreamer. Blow succeeded blow. One by one, his friends dropped off; his brothers, his beloved wife, his four sons - he survived them all; he stood alone at last, a stricken figure, in tragic and sublime isolation. Over eighty years old, he crawled thrice a week to deliver his lectures at San Demetrio; he still cultivated a small patch of ground with enfeebled arm, composing, for relaxation, poems and rhapsodies at the patriarchal age of eighty-eight! They will show you the trees under which he was wont to rest, the sunny views he loved, the very stones on which he sat; they will tell you anecdotes of his poverty - of an indigence such as we can scarcely credit. During the last months he was often thankful for a crust of bread, in exchange for which he would bring a sack of acorns, self-collected, to feed the giver’s pigs. Destitution of this kind, brought about by unswerving loyalty to an ideal, ceases to exist in its sordid manifestations; it exalts the sufferer. And his life’s work is there. Hitherto there had been no ‘Albanian Question’ to perplex the chanceries of Europe. He applied the match to the tinder; he conjured up that phantom which refuses to be laid.

He died, in 1903, at San Demetrio; and there lies entombed in the cemetery on the hillside, among the oaks.

But you will not easily find his grave.

His biographer indulges a poetic fancy in sketching the fair monument which a grateful country will presently rear to his memory on the snowy Acroceraunian heights. It might be well, meanwhile, if some simple commemorative stone were placed on the spot where he lies buried. Had he succumbed at his natal Macchia, this would have been done; but death overtook him in the alien parish of San Demetrio, and his remains were mingled with those of its poorest citizens. A micro-cosmic illustration of that clannish spirit of Albania which he had spent a lifetime in endeavouring to direct to nobler ends!

He was the Mazzini of his nation.

A Garibaldi, when the crisis comes, may possibly emerge from that tumultuous horde.

Where is the Cavour?

(1) In the earlier part of Rathgeber’s astonishing Grossgriechenland und Pythagoras (1866) will be found a good list of old maps of the country. (2) This was written before the outbreak of the Balkan war. (3) At San Demetrio there is now a simple and decent inn. I was there last in 1947. (4) There used to be regiments of these Albanians at Naples. In Pilati de Tassulo’s sane study (1777) they are spoken of as highly prized. (5) The identification of Saint Elias with Helios won’t do. (6) Thus his friend and compatriot, Dr Michele Marchianò, spells the name in a biography which I recommend to those who think there is no intellectual movement in South Italy. But he himself, at the very close of his life, in 1902, signs himself Ger. de Rhada. So this village of Macchia is spelt indifferently by Albanians as Maki or Makji. They have a fine Elizabethan contempt for orthography - as well they may have, with their thirty alphabets.

[Excerpt from: Norman Douglas, Old Calabria (London: Secker & Warburg 1915), chapters 22-24.]

Full text: www.authorama.com/...

TOP