| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

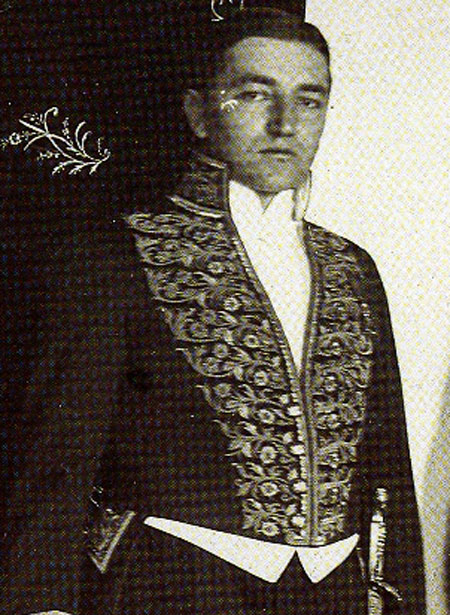

Carl Buchberger (1887-1974) as privy councillor of Prince Wied in Albania in 1914 (Photo: Marquis di San Giuliano collection).

1922

Carl Buchberger:

Memoirs of My Years in Albania,

1911 - 1914Carl Buchberger (1887-1974) was an Austrian diplomat who was seconded to serve Prince Wilhelm zu Wied during the latter’s brief reign in Albania in 1914. After his resignation in June of that year, Buchberger returned to the Austrian Foreign Service and served in The Hague, as civilian commissioner in Mitrovica/Kosovo (1916), in Berlin (1917-1924), as chargé d’affaires in Stockholm (1925-1933), and as Austrian ambassador to Turkey, Persia and Irak (1933-1938). During the Nazi period, he lived in exile in Sweden and took on Swedish citizenship. Buchberger published a short German-language history of the Principality of Albania under a pseudonym of Carl Thopia in 1916, and subsequently left the following personal memoirs, written around or after 1922, of his dramatic months in Durrës.

Count Berchtold was without doubt one of the most enthusiastic supporters of an independent Albania. His activities and endeavours were permeated by his honest enthusiasm for this goal. He regarded this Albania of his as a viable state and much lamented the lack of a unified central government in Albania where four different administrations had arisen in 1913: the provisional government under Ismail Kemal in Vlora, the government of central Albania in Durrës under the ever-scheming Essad Pasha Toptani that was hostile to the Vlora government and notoriously in Italian pay, the regime in Lezha under Ded Zogu, and the Mirdita government under Prenk Bib Doda. The country was in a sorry state – torn and divided politically. The issue of who was to take over the throne and create a unified central government was thus more pressing than ever.

The Conference of the Ambassadors in London promulgated statutes for the creation of Albania on 29 July 1913 that were to regulate the northern and southern borders and set up the International Control Commission, an institution that began its activities in Vlora on 15 October 1913. The work of establishing an Albanian gendarmerie was entrusted to Holland. The Dutch officers under the command of General De Veer arrived in Vlora at the end of October and got to work immediately.

The Choice of a Monarch for Albania

Deciding on the country’s monarch was the most pressing issue and required solution. Numerous candidates presented themselves for the Albanian throne, some directly and others indirectly. Among them were the Duke of Urach, Prince Ahmed Fuad of Egypt, the Duke of Teck, Prince Franz Josef of Battenberg, the Duke of Montpensier, Prince Louis Bonaparte, and Prince Wilhelm zu Wied. Italy rejected the Duke of Urach and Prince Battenberg as Catholics, whereas the Dual Monarchy was not in favour of the Muslim Prince Fuad.

Prince Wilhelm zu Wied (1876-1945),

Princess Sophie von Schönberg-Waldenburg

(1885-1936) and little Princess Marie Eleonore

(1909-1956), ca. 1914

(Photo: Library of Congress PPOC).

Italy was afraid that with a Catholic on the throne, the Dual Monarchy would have too much influence under the Austrian Kultusprotektorat. The two Powers finally came to an agreement that the monarch in question ought not to belong to any of Albania’s three religions, i.e. he should not be Catholic, Muslim or Orthodox. The only candidate left that filled this condition set forth by the two Powers was the Protestant Prince Wilhelm zu Wied.

Typical of the delicate situation concerning the selection of a monarch was the following incident that took place. In August 1913, the Vatican made a discreet attempt to impede the election of a Protestant as Albania’s monarch. The cardinal in question from the curia asked for a meeting with the Austro-Hungarian envoy to the Holy See in Rome during which he explained that the Vatican would obviously prefer to see a Catholic on the Albanian throne but had to refrain from expressing its preference because of categorical resistance from the Quirinal Palace. Italy was observing Austria jealously in the exercise of its Kultusprotektorat and would do whatever it could to subvert it. A Catholic monarch in Albania would seek support from the Vatican and thus create friction between Albania and Italy. The opposite would occur if a Protestant monarch were to be chosen. This was the reason behind Italy’s strategy. “Ma questo sarebbe un vero disastro [But this would be a veritable disaster],” the cardinal cried out. The Vatican was at any rate against a Protestant and regarded this as a calamity. Having explained in detail the reasons for the Vatican’s rejection of a Protestant candidate, he made the following surprising proposal. The Vatican regarded the selection of a Muslim candidate as the only possible solution! The cardinal then expressed his support for the candidacy of the Egyptian Prince Ahmed Fuad, with whom he was in contact. The Prince, he said, was ready to state in writing that he recognized the Austrian Kultusprotektorat without any reservations and would do nothing to impede its activities. The Dual Monarchy, however, rejected this candidate because he was opposed by most of the Albanian patriots. Prince Ahmed Fuad had trained in Italy as an officer, but was considered fickle and unreliable.

Austria-Hungary and Italy thus came to agree on a Protestant candidate in the person of Prince Wilhelm zu Wied. He was the younger brother of the sixth Prince of Wied, an old aristocratic family from the Rhineland who traced their ancestors back to the tenth century. Prince Wilhelm was born in 1876 and, as a 37-year-old, was perfectly suited to pose his candidacy. He served as a major in the third Uhlan Guard Regiment in Potsdam and received training in the general staff. He married Sophie, Princess of Schönberg-Waldenburg, in 1906 with whom he had two children: Princess Eleonore and Prince Karl Viktor, born in 1913. His mother was a Dutch princess and his aunt was the famed Queen Elisabeth of Romania, known by the poetic pseudonym of Carmen Sylva. Her husband was King Carol of Romania, from the Catholic Hohenzollern dynasty. Prince Wilhelm was an imposing, manly figure who was, by nature, however, very reserved. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany opposed his candidacy and regarded him as unsuitable “since the Prince is a weakling.” When Prince Wilhelm zu Wied visited his uncle, King Carol of Romania, in October 1913, he spent some time incognito in Vienna for consultations with Count Berchtold. Berchtold insisted that he should make a quick decision since the situation in Albania made this necessary. Prince Wied, who wanted to consult with his uncle first, hesitated for some time until he reached his decision. On 31 December 1913, he stated that he would accept the Albanian throne under the following conditions:

1. that the Six Powers agree to his candidacy,

2. that a deputation consisting of representatives from throughout Albania come to Germany and offer him the throne,

3. that Essad Pasha Toptani recognise the will of Europe and submit to him as monarch,

4. that the Great Powers provide a 4% loan of 75 million francs in installments; the first installment being 20 million francs,

5. that the Prince be accorded an annual income (civil list) of 200,000 francs,

6. that the Prince be empowered to authorise the draft for the organisation and administration of the country,

7. that the southern border of Albania be fixed.The Prince submitted these conditions in writing on 31 December 1913 to the German State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Herr von Jagow, who transmitted them to the Ambassadors of the Great Powers on 2 January 1914. In his letter, the Prince also referred to the issue of the future capital city of Albania, Elbasan having been suggested to him. After thorough consideration, he decided on Durrës as it was in the centre of the country, on the sea, and had a stone building that was suitable as a government residence. From Durrës that, like Vlora, was uninhabitable in the summer months due to malaria, they could easily transfer to Tirana, about 30 miles away, which was the only place suitable as a summer residence. All of these reasons spoke in favour of Durrës. The Prince had been warned against Durrës as a capital by some of the Great Powers because it would convey the impression that he was totally in the hands of the powerful Essad Pasha. This would create a negative impression throughout the rest of Albania.

That the domestic political situation was unstable became evident in Vlora in January with the discovery of a Young Turkish plot aimed at installing the Turkish Marshal Izzet Pasha, a native of Albania, on the Albanian throne. The Turkish officers who had landed in Vlora were swiftly arrested with the help of some of the Dutch officers who were already onsite. The investigation showed from confiscated documents that the plot had the support not only of the Turkish Government but also of Ismail Kemal in Vlora and of Essad Pasha in Durrës. Izzet Pasha himself stated from Constantinople that he would only present his candidacy with the support of Austria-Hungary and Italy and had nothing to do with the plot.

In order to clarify the domestic situation before the arrival of the Prince, the International Control Commission asked Ismail Kemal to resign, and took over interim rule until a government for all of Albania could be put in place. At the same time, it appointed the one-time minister of the interior, Fevzi Bey, as head of the administration for the districts of Vlora, Berat and Elbasan.

Essad Pasha Toptani (1863-1920)

in Ottoman uniform

(Photo: Marubbi 1913).

The Control Commission also decided to call for the resignation of the much more powerful Essad Pasha Toptani in Durrës and take over interim rule there, too. The Dual Monarchy agreed to the expansion of the powers of the Control Commission until the arrival of the Prince. It was essential to get Essad Pasha to resign after his arch-rival Ismail Kemal had done so, in order to avoid chaos in the country before the arrival of the Prince. The Control Commission sent its president, the British delegate, Consul General Lamb, and the German deputy delegate, Legation Counsellor Nadolny, to Durrës to negotiate with Essad Pasha. An agreement was reached after long discussions resulting in the resignation of Essad Pasha and the transfer of his competencies to the International Control Commission that appointed a director general of administration in the person of the former minister of finance of the provisional government of Vlora, Aziz Pasha. The Commission also accepted one of Essad Pasha’s conditions, namely that he be placed at the head of the deputation that would travel to Germany to offer the Albanian throne to Prince Wied. The agreement for the resignation of Essad Pasha also approved of his financial doings and was signed by all of the Control Commission delegates who had by then arrived in Durrës. Consul General Lamb and Legation Counsellor Nadolny swiftly put together the members of the deputation, comprising men from throughout the country. I have found the list of members in my notes. It was as follows:

Essad Pasha Toptani

Mr Kakariqi and M. Giobba

Hussein bey Vrioni

Hasan bey Prishtina and Mr Milto Shalvari

Samy bey Vrioni

Ekrem bey Vlora

Djemil bey Vlora

Elias bey Vrioni and Mr Gumurtaga

Mr Lef Nosi and Sefket bey

Vehbi Efendi (mufti of Dibra)

Mr Jusuf Kanina

Dr Turtulli and Mr Abdul Upi

Dr Koleka and Ekrem bey Libohovapresident

delegates of Shkodra

delegate of Puka

delegates of Durrës

delegate of Tirana

delegate of Shijak

delegate of Peqin

delegates of Berat

delegates of Elbasan

delegate of Dibra

delegate of Vlora

delegates of Korça

delegates of GjirokastraOn 14 February 1914, Essad Pasha set off at the head of the above-mentioned 18-member deputation for Bari on board an Italian steamer to reach Neuwied via Italy. In the bay of Durrës he held an impromptu speech before the people gathered there in which he called for brotherhood between Muslims and Christians and obedience to the new “king.”

I was particularly interested in these events as I had been appointed in early January as a representative of the Austro-Hungarian delegation to the International Control Commission in Vlora.

In mid-January, before my departure, a cable arrived calling me to Vienna where the Ministry of Foreign Affairs informed me that Prince Wilhelm zu Wied had spoken to the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in Berlin and expressed his wish to have me as a member of the civilian cabinet of his privy council to be composed of an Austrian and an Italian. At the same time, the Prince asked the Italian Ambassador in Berlin, Mr Bollati, to give him Captain M. F. Castoldi as the Italian privy councillor.

Although I was quite surprised by all of this, I was not entirely unprepared. The German delegate to the International Border Commission for Southern Albania, Major Thierry, a wise and hard-headed man, had been keenly observing the problems in Albania and the rivalry between Austria and Italy, and wanted to support his fellow officer in the Uhlan Guards, Major Prince zu Wied. He regarded it as essential that the Prince, as Albania’s monarch, should have reliable advisors who not only knew Albania, but would also be able to discuss and solve any difficulties arising from Austro-Italian rivalry. Thierry decided that the best and simplest solution were Castoldi and Buchberger whom he knew had co-operated well on the southern Albanian border commission and thought this co-operation ought to be continued directly under the Prince. He therefore proposed our names to Prince zu Wied and to the Foreign Ministry in Berlin. This was theoretically a very good idea and I began to think about how it could be implemented. Since I was particularly interested in Albania and its people that I had come to know and love, I was attracted by the prospect of new duties, however difficult they may have seemed. I was of course well aware that, at my age, I did not have the experience of my older college Castoldi who had worked in Macedonia for several years. What I sensed would be complicated was for us to provide the Prince with joint recommendations we both agreed upon, not only because the Albanian government would not take kindly to the presence of foreign advisors, but also because the Prince would be subject to the influence of the heads of missions of the Powers. A privy councillor would be powerless in comparison. Our job was thus rather like squaring the circle. What made it all the more complicated was the rivalry between Austria and Italy which would be reflected to a good extent in the personal relations between the envoys of the two Powers. I was also very concerned about the chaotic situation in the country itself. The prospects for positive developments in the future did not look good. Indeed, I had serious doubts as to whether the new Principality would last long, unless the new monarch were particularly gifted in running affairs of state and unless he had great courage and a good deal of luck. I therefore had to overcome many reservations of my own before I could accept the position. Count Berchtold made things much easier for me by promising kindly and spontaneously that I could re-enter the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Service at any time and preserve my rank. Despite all the negative aspects, I thus agreed to take up the position as privy councillor in the civilian cabinet of the Prince of Albania and, after being granted leave for a year, I set off for Berlin and Potsdam to present myself to the Prince and learn exactly what the position would involve. The Prince received me in the presence of his wife who was apparently the driving force behind his candidacy. The Princess seemed to have a strong personality despite her delicate appearance and looked forward to the mission with great ambition and romantic ideas. The Prince, on the other hand, was serious and pragmatic. He discussed my coming duties with me and inquired in detail about the situation in Albania. Having been trained in the Prussian general staff, he considered every question thoroughly before asking it and did not make any rash decisions.

In Berlin I met my colleague, Captain Castoldi, who ensured me of his genuine friendship since our time together in Albania and stressed emphatically that he would not sully it by any intrigues that would harm the Prince and the land we were to serve or that would be to the detriment of our harmonious co-operation. I still have the letters in which he made these promises. Castoldi was an intelligent, lively fellow who had la parole facile [the gift of the gab]. He was candid and honest by nature. We began our joint tasks in Berlin, discussed the details of our job and decided there and then to set up house together in Durrës in order to make our work with the Prince easier.

At the end of January, France and Russia answered the Prince through their ambassadors in Berlin, stating that they had received his message with regard to his acceptance of the Albanian throne and that the condition he mentioned with regard to an advance on the loan was still being discussed between Austria-Hungary and Italy. The latter two Powers had by this time agreed to provide the Prince with an immediate advance of ten million on the loan and, as such, he was able to accept the throne. On 6 February 1914, the Prince informed Herr von Jagow in writing of the advance provided by Austria-Hungary and Italy and of his acceptance of the throne, adding that he had also informed all of the other Great Powers of his acceptance via their ambassadors in Berlin.

Thus began a regal dream that was to turn into a nightmare in a mere 200 days.

The Prince set off on his journey to visit the various capitals of Europe to present himself to the governments in question. Vienna was slightly offended by the fact that he began his trip in Rome on 10 February 1914. In Rome he was informed that the plan for his journey to Albania on board an Austro-Hungarian warship, the Taurus, had upset the Italians because they regarded this as him giving preference to Austria-Hungary over Italy.

The Prince was, however, warmly received in Rome. He was accorded an audience by King Victor Emmanuel and given the highest Italian medal of distinction, the Annunciation Order. He was invited to a festive banquet at the court and had dinner at the German Embassy the next day with Prime Minister Giolitti and Foreign Minister Marchese di San Giuliano. It is said, however, that the Prince did not make a particularly good impression in Rome. He was seen as being too reserved and as not taking an interest in his mission. In his memoirs, Giolitti wrote that neither he nor San Giuliano regarded the Prince as the right man for Albania. The Prince did not visit the Vatican as he was afraid this might cause a negative reaction in Italian government circles.

From Rome the Prince travelled to Vienna for his first visit there on 14 and 15 February. I joined him in Pontafel [Pontebba] and began my service as privy councillor during this two-day stay in Vienna. These were very hectic days for me. There was a constant stream of visitors to Hotel Imperial where the Prince was staying as a guest of the Emperor. Equally constant was my work in arranging for the Prince’s meetings with the various archdukes and ambassadors. Following an audience with the Emperor Franz Josef I at Schönbrunn Palace, there was a state banquet attended by the highest dignitaries of the Dual Monarchy and by the German Ambassador, Herr von Tschirschky. I was invited, too. Following the dinner, that was served quickly on the Emperor’s orders as usual, and was soon over, the Emperor held audience with a more intimate circle. As part of it, Count Berchtold presented me to His Majesty, who engaged me in a long conversation. The Emperor told me that he had read my reports from southern Albania with great interest and thanked me for the success of the mission. He was very surprised by the constant difficulties caused by the French and the resistance they showed, something which he deplored. I was quite amazed at the lively interest the Emperor took in the events going on in Albania, despite his advanced age. He could even recall details from my reports. This was further proof of interest throughout Austria in the creation of Albania as an independent state. At that time, the creation of new states was a rarity indeed.

The impression the Prince left in Vienna was much better than in Rome. Count Berchtold was very impressed by the Prince’s interest in all the issues concerning Albania. Section Head, Dr. von Thallóczy, gave the Prince a long lecture about Albania which he listened to with great interest.

After Vienna, the Prince visited London, Paris and Petersburg where everything went reasonably well. In Paris they stressed that it was very much in Albania’s interest that the international character of its creation as an independent state not be forgotten.

We were, of course, well aware of Russia’s negative attitude to the creation of an independent Albania. The Russian Foreign Minister, Sazonov, used every opportunity, suitable or not, to make tactless and sarcastic remarks about the “Albanian experiment,” even in front of the German and Austro-Hungarian ambassadors. The Russian representative in Vlora, Petrajev, reported that Albania was in a state of complete anarchy and was on the point of collapse. Russia always supported the attribution of border regions to Serbia and Greece. The rest of Albania, in its view, was to be given to some Muslim prince because a Christian monarch would never survive in Albania. Nonetheless, the Prince had the opportunity in Petersburg to tell Tsar Nicholas that a million Albanian had been given to Serbia. The tsar was very surprised by it because both Sazonov and the Serbian Prime Minister Pašić who had been in Petersburg a short time beforehand had obviously kept it a secret from him.

On 21 February 1914, Prince Wilhelm zu Wied and his wife, Princess Sophie, received the Albanian deputation under Essad Pasha at Neuwied Palace, the ancestral seat of the Wied dynasty. They had come to Neuwied to offer him the Albanian throne. On this occasion, Essad Pasha held the following speech:

Altesse!

La Délégation, qui a l’insigne honneur sous ma présidence de se présenter devant Votre Altesse pour La prier d’accepter le trône et la couronne de l’Albanie libre et indépendante, se considère excessivement heureuse de pouvoir accomplir aujourd’hui sa mission, dont elle est investie par toute l’Albanie.

Altesse, Notre Nation qui a si acharnement combattu autrefois pour son indépendance, a dû passer plus tard des périodes de malheur, mais elle n’a jamais oublié ni son glorieux passé, ni son skipétarisme et a su conserver l’esprit National et la langue de ses pères.

Les changements politiques survenus dernièrement dans les pays balkaniques et les soins et l’aide bienveillants de Grandes Puissances Européennes ont permis à l’Albanie de se constituer en Etat libre et indépendant et les Albanais sont très heureux et fiers que Votre Altesse, fils d’une Nation grande en science, en civilisation et en gloire ait accepté d’en être le souverain.

Que le Tout Puissant protège Votre Altesse et Son Auguste famille pour le bien de l’Albanie!

Les Albanais sans exception seront toujours fidèles sujets de Votre Altesse et prêts à aider Vos efforts pour conduire le peuple Albanais vers un avenir heureux et glorieux.

Vive Sa Majesté Guillaume I., Roi d’Albanie!

[“Your Highness,

The delegation under my presidency that has the honour and distinction of presenting itself to Your Highness to beg You to accept the throne and crown of a free and independent Albania, considers itself extremely happy to be able to fulfil the mission with which it was invested by all of Albania.

Your Highness, our Nation which once struggled so fiercely for its independence, later went through periods of misfortune, but it never forgot its glorious past nor its Albanian roots, and was able to preserve its national spirit and the language of its fathers.

The political changes that have taken place in the Balkan countries recently and the care and kindly assistance provided by the Great Powers of Europe have enabled Albania to become a free and independent country, and the Albanians are very glad and proud that Your Highness, scion of a great Nation noted for science, civilization and glory, has accepted to become their sovereign.

May the Almighty protect your Highness and His noble family for the well-being of Albania.

The Albanians, without exception, will always be the loyal subjects of Your Highness and will be ever ready to support Your efforts to lead the Albanian people towards a happy and glorious future.

Long live His Majesty, William I, King of Albania.”]

This was the first time that the Prince and the brutal, ruthless and inordinately ambitious Essad Pasha, who as the ruler of central Albania had recently been involved in a Young Turkish plot to overthrow the provisional government of Ismail Kemal in Vlora, had stood face to face.

With his polite and endearing address, Essad Pasha perhaps intended to fulfil the Prince’s condition for the throne, i.e. his submission to Prince Wilhelm. At any rate, if it was really submission, it did not last for long!

Vienna was upset that the Albanian deputation travelled from Durrës to Neuwied through Italy and did not take the shortest route via Trieste. They had expected that the deputation would stop over for an initial visit in Vienna. The Italian government, however, did everything in its power, with the help of its consul, to ensure that the deputation and Essad Pasha first go to Rome, where they were festively welcomed. King Victor Emmanuel received Essad Pasha in a special audience in order to stress the value that Italy placed upon him!

I myself was not in Neuwied. Castoldi accompanied Essad and the delegation from Rime directly to Neuwied and did not inform me of the date of the reception there. It was only at noon on 21 February that I received a cable from the Prince telling me to be at Waldenburg in Saxony on 22 February where Princess Sophie’s brother, Prince Otto von Schönburg-Waldenburg, was to receive the Albanian deputation at his palace in Waldenburg. I arrived in time and took part in the gala luncheon and following reception which was festive indeed. I was able to greet the members of the deputation, some of whom, such as Hasan bey Prishtina and Ekrem bey Vlora, I had met earlier. It was on this occasion that I met Essad Pasha. Prince Otto von Schönburg-Waldenburg welcomed his Albanian guests warmly at the gala luncheon, expressing his assurance that their country would enjoy a great future under the royal couple.

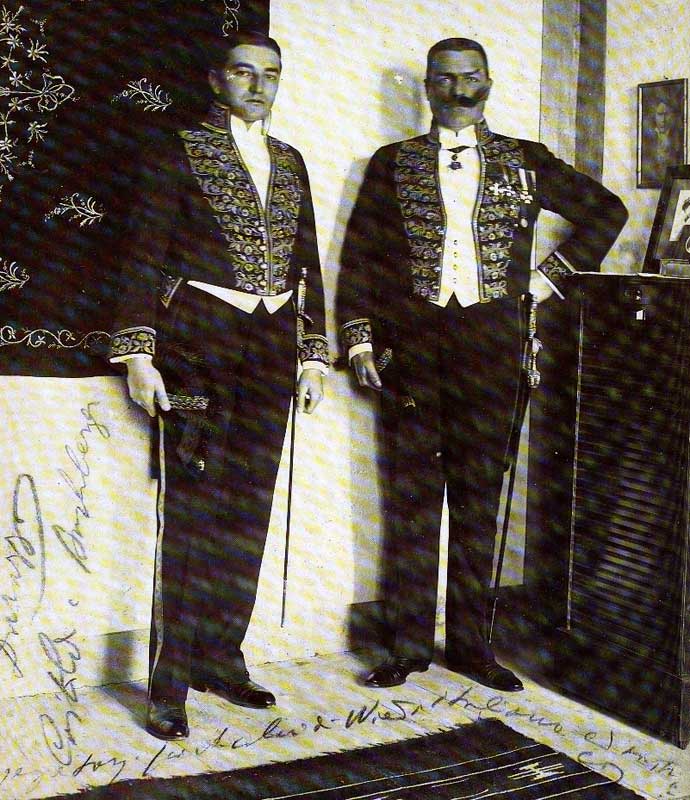

Carl Buchberger (l.) and

Captain Fortunato Castoldi (r)

as privy councillors of Prince Wied

in Albania in 1914

(Photo: Marquis di San Giuliano collection).

Castoldi apologized for not having informed me of the Neuwied reception, pleading that it had been forgotten amidst all the confusion of the visit in Rome. I replied that I hoped it was not a bad omen for the future of our co-operation.

As the deputation was to continue from Waldenburg on to Vienna, I discussed the programme with them and dealt with their wishes.

The delegation wanted to spend a day in Berlin, so I hastened to Vienna to arrange the definitive programme for their three-day visit there (24-27 February 1914). For months, the newspapers had been full of articles about the creation of an independent Albania and about the crises surrounding this event, even the danger of war. The Dual Monarchy had indeed twice been on the brink of war with the ultimatum it delivered to Serbia and Montenegro. All of Vienna now seemed to be on its feet in the hopes of catching a glimpse of the Albanian deputation and its president Essad Pasha. An Austrian ‘Albania Committee’ under privy councillor Prince Liechtenstein and a Society for the Promotion of Albania had been set up in Vienna. Proof of the lively interest in Albania were the countless questions, in writing and by telephone, that I had to deal with. Many people wanted to know what possibilities there were for industrial and commercial activities in Albania.

The deputation was ceremoniously welcomed on its arrival and accompanied to the hotel. What was evident was how Essad Pasha stressed his prominent role in Albania by always keeping himself apart from the delegation. He did not stay at the same hotel with the rest of them, but rather at Hotel Imperial where special guests of honour were wont to be lodged. As part of the visit, the deputation was to be received in an audience by the Emperor Franz Josef I who, despite his advanced age, wished to meet all the members of the delegation at Schönbrunn personally. For Essad Pasha we had to arrange a special audience because he refused to take part in the audience with the deputation and pointed to court etiquette in Rome, where he had been accorded a private audience with King Victor Emmanuel. We of course treated Essad Pasha with kid gloves and strove to create the impression that we did not know how notoriously linked he was with Italy and Serbia.

During the audience of the deputation at Schönbrunn, I had the honour of presenting its members to His Majesty, one by one, and to interpret the conversations the Emperor held with each of the delegates. The Emperor stressed again and again the great interest of the Dual Monarchy in developments in Albania.

Baron Carlo Aliotti (1870-1923),

Italian envoy to the court of Prince Wied

in Durrës in 1914

(Photo: Marquis di San Giuliano collection).

The next day, I accompanied Essad Pasha and the deputation to the Theresian Military Academy in Wiener Neustadt, in which officers of the Austro-Hungarian armed forces had been trained for over 150 years. Essad Pasha, whose side I never left, was welcomed by the Commander of the Academy, Major General von Roth, and was very impressed by the renowned institution. He asked many questions that I interpreted for him. We conversed in Turkish since Essad Pasha spoke Turkish and Albanian, and my knowledge of Turkish was better than my Albanian.

On the following day I was asked to accompany Essad Pasha to his private audience with His Majesty and interpret for them. In line with court ceremony, we arrived in tails at ten in the morning. Essad Pasha greeted the Emperor warmly and thanked him with exuberance for the honour of being accorded a private audience and for his reception at the Military Academy which had greatly pleased him because he was a professional soldier. Essad then outlined his plans for the creation of an Albanian army which he regarded as the top priority for the near future. The Emperor listened attentively and noted kindly that he hoped Essad Pasha would be able to find a minister of finance who could drum up the millions that would be required to implement such a project. The Emperor then asked a number of questions about Albania’s economic situation. At the conclusion of the audience, His Majesty stated that Austria-Hungary was following developments in Albania with great interest and would always promote and support the country. He hoped that the new sovereign, whom he had recently met in Vienna, would be able to achieve unity in the country for the benefit of its development. Essad Pasha assured the Emperor of his loyalty to the new monarch whom he would support in the interests of his country.

Essad Pasha was extremely satisfied with the private audience. He was not a talkative man, but he thanked me for my assistance in making his stay in Vienna as pleasant as possible. On the evening of 26 February, I accompanied Essad Pasha and the deputation to their train for Trieste, from where they were to return to Durrës on board the Austrian Lloyd. Essad Pasha would see the royal couple again on their arrival in Durrës on 7 March.

On 2 March I received cabled instructions in Albania from the Prince telling me to be in Trieste on 4 March where Castoldi had also arrived. We all left Trieste for Durrës on board the Austro-Hungarian ship Taurus on 5 March, the royal couple and their entourage having reached Trieste the day before.

The entourage consisted of the Prince’s marshal Major von Trotha, his private secretary Captain Heaton Armstrong, and the lady of the court Mrs von Oidtmann. In Durrës another lady of the court, Miss von Pfuel, joined us as did two Albanian chamberlains, Sami bey Vrioni and Major Ekrem Libohova.

The Prince’s civilian cabinet consisted of the two cabinet members Castoldi and Buchberger.

Accommodation on the Taurus was excellent and we took our meals together, where we had an opportunity to discuss the telegrams that had come in about various matters. After dinner in the evening, we sat in the salon and listened to the musically talented Princess sing.

The journey down the Dalmatian coast in the fine sunny weather, past Ragusa [Dubrovnik] and the Bocche di Cattaro [Bay of Kotor], provided us with a good rest after the hectic weeks and all the receptions, gala dinners, visits and excursions. However, the good weather did not entirely relieve me of the worries I had about the uncertain future that stood before the royal couple.

The Two Hundred Days of the Principality of Albania

The Taurus dropped anchor in the Bay of Durrës on 7 March 1914. The royal couple and their entourage went on land where Essad Pasha in his new uniform as an Albanian general, the members of the government and representatives of the International Control Commission were waiting to greet them. Great crowds had gathered at the wharf to see with their own eyes the Prince and the Princess who proceeded to the konak that had been adapted to serve as their residence. The crowds shouted “Rroft Shqipënija! [Long live Albania!]” and applauded the royal couple again and again who appeared on the balcony and thanked them. This was the monarch’s only happy day in Albania.

Castoldi and I had made arrangements for our accommodation before arriving. We leased the house of Abdi bey Toptani, a cousin and opponent of Essad Pasha, at the edge of town and set up household together, with a Hungarian cook and an Austrian and an Italian servant. The distance from the konak and our “inseparable co-existence” made our difficult job easier, but in the final analysis, the success of our co-operation depended on agreement between the envoys of our two countries in Albania.

The prerequisites for this co-operation were not good from the start because the temperaments of the two envoys, Ritter von Löwenthal-Lina for Austria-Hungary and Baron Aliotti for Italy, were too diverse for them to achieve a harmonious modus vivendi, in particular the methods they used to achieve their aims.

Baron Aliotti stemmed from a Levantine family, was very independent by nature and conducted his own policies that went far beyond the guidelines agreed upon by the governments of the two Powers responsible for Albania. He had his own methods in diplomacy and did not seem to bother too much about his government’s directives. In his reports he painted a negative picture of Albania under the Prince, more negative that it was in reality, and did so in order to stress its defects. The essence of his reports was that Albania was doom to failure. In everything he did, he was determined to make propaganda for Italy and carve a strong position out for himself with the Italian press, with Italian representatives in Durrës and among members of the Italian parliament in Rome. They looked upon him as “Garibaldi” in Albania. Of course he always relied on Essad Pasha as the most powerful leader in the country, who was in Italy’s pay, and strengthened the latter’s position. In view of his activities and the charisma that he brought to bear with great finesse, he soon enjoyed great reputation in Rome such that he was able to keep his own foreign minister, San Giuliano, in check. Aliotti gave Essad all the support he needed, but gave the Prince none. We will never know whether it was official Italian policy to give free rein to its official representative in Albania because, deep down, it was following the same course, but could not do so openly because of its alliance with Austria-Hungary.

Heinrich Ritter Löwenthal von Linau

(1870-1915), the Austro-Hungarian envoy

to the court of Prince Wied,

talking to the bearded Turhan Pasha Përmeti

(1839-1927) in Durrës in the spring of 1914

(Marquis di San Giuliano collection).In a meeting that Count Berchtold held in Abbazia [Opatija] in mid April 1914, the Italian Foreign Minister Marchese di San Giuliano assured him that Italy remained, as always, in close agreement with Austria-Hungary on Albania and that Baron Aliotti had been ordered to give Prince Wilhelm all the support he needed. San Giuliano made this statement when Count Berchtold referred specifically to the very negative reports that Baron Aliotti had been sending back about the untenable nature of the current situation in Albania.

Aliotti’s opposite number was the Austro-Hungarian envoy Ritter von Löwenthal-Linau – de mortuis nil nisi bene – who stemmed from a rich Viennese family with much property. After finishing his studies in law, he joined the foreign service and served in Dresden, Tokyo, Washington and Athens. Before his appointment in Durrës, he had been counsellor at the embassy in Constantinople. As opposed to Aliotti, he was not independent-minded. In everything he did, he sought advice from Vienna. Unfortunately, he was very nervous, easily upset and did not like to take decisions on his own. Though he was easily influenced by others, he was paranoid about all the plots and doings in Durrës among the many diplomats, businessmen, politicians and journalists. He was thus no match for the refined and clever Aliotti.

Both governments had chosen the wrong man. When the Austro-Hungarian government suggested that the representatives in Durrës be changed, San Giuliano countered that he was unable to do this because Aliotti’s position in Rome was so strong that he – San Giuliano – would probably be the one to go!

An objective account of the tragic course of the 200 days of the Principality of Albania has been given in the historical study Das Fürstentum Albanien [The Principality of Albania] published by a friend of mine in the two-volume edition Illyrisch-Albanische Studien [Illyrian and Albanian Studies] edited by my teacher and patron Dr Ludwig von Thallóczy. As I am recording my memories here and not writing history, I will limit myself to what I observed personally. Since that time, other works have been published in Austria and Germany that contain documents and much new material on the causes and connections which were obscure at the time and have now become clearer.

The reading of these documents makes it painfully evident that the course of the 200 days in question was determined in good part by the unfortunate relationship between the two Powers, a relationship that took on grotesque forms. Instead of harmony, there was open confrontation in the relations between the two heads of mission.

The rivalry of the Great Powers for dominance in the Mediterranean was played out in Albania, too, in particular since the issue of the evacuation of Epirus by Greek troops was linked, at England’s suggestion, to the island issue, because England would not tolerate Italian claims to the islands of the Aegean.

There was no room amidst all the confusion and political intrigues for the rise and development of an Albanian state. The Prince relied on the conservative Albanian beys in order to counter the power of Essad Pasha. Fortunately, there was a national party made up of intelligent circles in the country. Its leaders stemmed in particular from Korça. Among them were Mid’hat bey Frashëri, Faik bey Konitza and the Orthodox priest, Fan Noli. In their foreign policy, they tended towards Austria-Hungary which had no ulterior motives. They mistrusted Italy’s friendly attitude towards Albania. Although this national party had supporters from all three parts of the country, it was not able to rise to power, the circumstances being what they were.

Of all the problems that needed to be solved, the most important one was southern Albania. The territory accorded to Albania under the Protocol of Florence of 17 December 1913 was still occupied by Greece in March 1914. Greek troops took their time to withdraw because the evacuation of Epirus was linked to the island issue. As feared and predicted, Greek duplicity gave rise to a rebel government in Gjirokastra led by the one-time governor of Janina, Mr Christaki Zographos, with Mr Karapanos as foreign minister, and their “sacred legions” marauded in the villages with fire and sword. The new Albanian state had no means at its disposal, neither sufficient quantities of militia troops nor gendarmerie, to act against the unsacred doings of the sacred legions, increased in size as they were by Greek deserters. It was unable to liberate southern Albania and install an Albanian administration there. All that it could do was to maintain contact with the rebels. Following the unfortunate mission of the Dutch Major Thomson, who was sent to Gjirokastra as commissioner general to conduct technical talks and who involved himself instead in political negotiations and was therefore recalled, the International Control Commission was authorized to hold discussions with Mr Karapanos. These discussions took place in Corfu. An agreement was signed on 17 May 1914 and was to be implemented under the aegis of the Great Powers. The conditions were unacceptable for Albania because the two provinces of Korça and Gjirokastra were given an “autonomous regime” and were thus to have a special status in Albania. It was only because Albania was completely paralyzed at the time that the Prince and his government under Turhan Pasha agreed to ratify the agreement on 23 June, after the Great Powers ratified it on 18 June. The internationalisation of the Corfu negotiations came to a sad end and the two provinces were recognized as having a caractère allogène. Nothing good could be expected of the Control Commission, composed as it was of notorious foes of Albania such as the French and Russian delegates, Krajewski and Petrajev. The attitude of Germany towards Greece was influenced by the close relationship between King Constantine and Kaiser Wilhelm, Constantine being the latter’s brother-in-law. This precluded energetic support for Austro-Hungarian and Italian demands in Athens, in particular since Constantine let it be known that his country might join the Triple Alliance if Greece were given leeway in this issue.

Greek propaganda, that never ceased proclaiming urbi et orbi the exclusively Greek character of all of Epirus, succeeded in deceiving the German diplomats in Athens. They made the absurd assertion that with the delineation of the border, Italy, which had greater interests in southern Albania than Austria-Hungary, had given proof that it was not interested in an independent Albania. Since Italy was well aware of the ethnic composition of Epirus, it knew in advance what repercussions the new southern border would have. […] It is interesting to note that after the First World War, when Albania was negotiating on the border issue at the ambassadors’ conference appointed by the League of Nations, the conference, at its session on 9 November 1921, opted for the southern border in the Protocol of Florence of 17 December 1913, with a few very minor rectifications. I regard this as posthumous but complete recognition of the work of the International Border Commission on southern Albania in 1913.

Essad Pasha’s role in the Principality was that of a strongman in Italy’s pay. He played both minister of war and minister of the interior, yet he sabotaged the establishment of a militia and the attempts of the Dutch officers to reorganise the gendarmerie. He was determined to be the number one man after the Prince and the “coming man” should the Prince fail. Aliotti did nothing to support the Prince, whom he had already given up, but did all he could to further Essad’s ambitions.

The rivalry between the two Powers proved fatal to the Principality. The tenuous relations between the two envoys deteriorated into open hostility after the coup against Essad on 19 May 1914 in which he was arrested and expelled from the country, all of this taking place while Aliotti was in Rome. It is still unclear who, in the conflict between Essad Pasha and the town commander, the Dutch Major Sluys, ordered Austro-Hungarian troops to open fire on Essad’s house with their mountain guns in the middle of the night and force Essad to capitulate. The Prince denied taking any initiative in this connection. In an interview given in Berlin, the marshal of the court, Major von Trotha, later stated that he was responsible, apparently, as was rumoured, in order to protect the Princess from harm.

The population of Durrës was greatly relieved at the fall of the hated Essad and at his expulsion. Baron Aliotti, on the other hand, was not at all amused when he got back to Albania. It was not long before he instigated a counter-coup in revenge against the Austrians whom he unjustly suspected of being behind the action on 19 May. A peasant revolt of Muslim Albanians broke out in Shijak near Durrës that demanded the removal of the Christian prince. Instigated by the Young Turks, it received much support, as did all of Aliotti’s actions against the Prince. On 24 May Aliotti appeared in all haste before the Prince, painted a dramatic picture of the imminent danger in Durrës that was being attacked by a mob of 7,000 rebels, and urged the Prince to withdraw with his family and take refuge on board the Italian yacht Misurata. The Italian naval detachment was withdrawn from the palace and the Albanian flag was raised on the Misurata, next to the Italian. The Prince was forced to seek Italy’s protection. Aliotti had taken his revenge! The coup and counter-coup had taken place within a short period of time and led to extreme tension between Aliotti and Löwenthal. This tension had fatal repercussion for the working relationship between the two members of the Prince’s civilian cabinet. One of us was accused of taking part in the removal of Essad and the other in the counter-coup.

Our work in the civilian cabinet consisted of dealing with the sovereign’s correspondence, and with official requests made of him. I can recall a request for Albanian citizenship submitted by the famous actor, Alexander Moissi, who was an Albanian from Kavaja. This was granted. We discussed all the political problems of the day with the Prince, especially the southern Albania issue, and received instructions from him. Castoldi as a military man dealt with the militia issue. We informed one another of the instructions we had received and discussed them at meals. Whether or not Castoldi was also receiving secret instructions from the Italian envoy Aliotti to support Italy’s interests, I do not know. What I am, however, sure of is that, if Aliotti did issue any such instructions, they had no influence on the Prince, who was highly suspicious of Italy. Herr von Löwenthal, who saw treason around every corner, was suspicious of the institution of the civilian cabinet, as was the Albanian government that refused to sanction our work with a written agreement.

At the end of May, the hopelessness of my situation, the hopelessness of the situation of the Principality and the impossibility of doing any positive service to Albania moved me to submit my resignation verbally to the Prince. I suggested that he abolish the institution of the civilian cabinet because it required harmonious co-operation between the two Powers. It was also opposed by the Albanian government. When I informed Castoldi of my decision, he was very much opposed to it and went to see the Italian envoy to discuss the situation. The Prince, who was suspicious of Italian intrigues against him, with or without Castoldi, followed my suggestion and abolished the civilian cabinet with its two members. When Aliotti protested and asked for his reasons, the Prince responded ‘undiplomatically’ but honestly by saying that he no longer trusted Castoldi. The situation was complicated. I had resigned and waived any claim for compensation. Castoldi was dismissed, but Aliotti demanded compensation for him, i.e. a position as secretary of state in the Albanian Ministry of War. Herr von Löwenthal protested energetically about this. A Solomon-like solution was found with the Prince informing both of his cabinet members in writing that, as a result of a re-organisation “des services de mon gouvernement” [of the services of my government], our services would no longer be required. This was following by a polite passage in which the Prince thanked us for our invaluable contributions. The letter was dated 11 June 1914 and bore the seal “Sécrétariat Privé de S. M. le Roi d’Albanie” [Private Secretariat of H. M. the King of Albania]. Our joint household was dissolved in disharmony. Each of us made his way home. Löwenthal was delighted, but Aliotti was not pleased at all.

The situation of the Principality became more and more untenable. Its borders hardly stretched beyond Durrës. The rebels camped outside the capital had been reinforced and were demanding a Muslim monarch in the person of the Turkish marshal Izzet Pasha, a native Albanian. An Italian emissary, Colonel Muricchio, was arrested in Durrës because he had been observed sending signal to the rebels from his house in town. This was, at any rate, an indication that the Italians were behind the Muslim rebels.

The Albanian government under the aging Turhan Pasha was powerless. All of its endeavours to get international troop detachments or Romanian troops had failed, as had its request for a reinforcement of the naval units in the Bay of Durrës. Austria-Hungary and Italy rejected any further co-operation over Albania, understandably in view of the fact that all co-operation up to that point had been fruitless. This attitude of abandonment was reinforced by Germany that feared a deterioration of relations between Austria and Italy and thus a weakening of the Triple Entente. Germany was convinced that an Austro-Italian condominium in Albania would turn into another Schleswig-Holstein of 1864. It was constantly mediating between its two allies to avoid a breakup.

In view of the hopeless situation of the Principality, all of the Great Powers agreed more or less that the provisional administration of Albania should be taken over by the International Control Commission. But since the Powers gave the International Commission no more troops and naval units than they had given the Prince, this internationalisation was equally bound to fail, just as the Principality had, in particular since some of the delegates, with anti-Albanian intentions, were working towards the country’s demise.

Despite his failings, it would be unjust to blame the Prince for the collapse of his reign. The Prince was powerless and unable to exert any influence upon his subjects amidst the murky intrigues of the Great Powers and the tragedy of the collapse of Austro-Italian co-operation. Princess Sophie, who was a very talented and intelligent woman, described the situation of the royal couple succinctly in a letter to the Queen of Romania in June 1914: “With no army, no money, no knowledge of the language, surrounded as we are by a pack of desperate associates and dubious influence from abroad, our situation is terrible. Yet we will remain steadfast.” Even those who had been called upon to support the Prince acted to bring about his downfall. Italy did not want an independent, strong Albania because it had ambitions of its own there. Russia and France were in favour of dividing Albania up among their protégés, Greece and Serbia. As opposed to them, Austria-Hungary had a clear and genuine interest in the independence and strengthening of Albania. This conflict of interests brought about the end of Austro-Italian co-operation which accelerated the downfall of the Principality. Its final demise was caused by the World War.

The outbreak of the World War on 1 August 1914 caused the Great Powers to forget Albania entirely. The International Control Commission fell apart and all Austro-Italian co-operation stopped.

On 3 September 1914 the Prince and the Princess left Durrës on the Italian yacht that took them to Venice. From there, they proceeded to Romania without ever abdicating.

[from: Carl Buchberger, Erinnerungen aus meinen albanischen Jahren 1911-1914, in: Studia Albanica, Tirana, 1973, 1, pp. 237-254. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP