| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

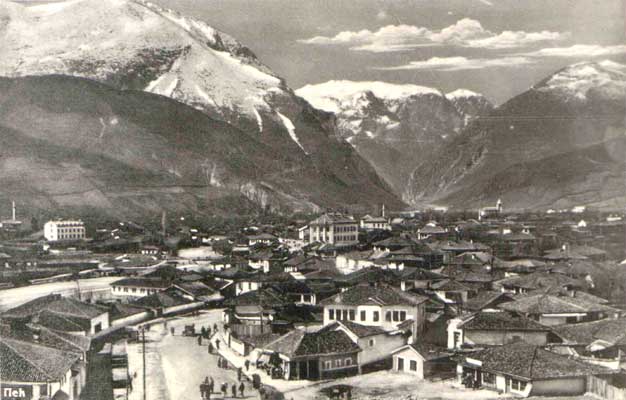

View of Peja (Pec) in the 1920s.

1930

Gjon Bisaku,

Shtjefën Kurti & Luigj Gashi:

The Situation of the Albanian Minority

in Yugoslavia

Memorandum Presented to the

League of NationsThis memorandum, originally written in French, was addressed to the League of Nations in 1930 by three Catholic priests, Gjon Bisaku, Shtjefën Kurti, Luigj Gashi, who had been working in Kosova in the 1920s on behalf of the Sacred Congregation of the Propaganda Fide in Rome. Their desperate appeal shows that the situation of the Albanians in Kosova had not much improved a generation after the Serb takeover of 1913.

TO HIS EXCELLENCY MR ERIC DRUMMOND,

Secretary General of the League of Nations,

GenevaExcellency,

We, the under-signed,

Dom Gjon Bisaku of Prizren, until recently priest in the parish of Bec, District of Gjakova / Djakovica, Yugoslavia;

Dom Shtjefën Kurti of Prizren, until recently priest in the parish of Novosella / Novoselo, District of Gjakova / Djakovica, Yugoslavia;

Dom Luigj Gashi of Skopje, until recently priest in the parish of Smaç / Smac, District of Gjakova / Djakovica, Yugoslavia;

all three of us being missionaries of the Sacred Congregation of the Propaganda Fide, and Yugoslav citizens of Albanian nationality,

have the honour to submit to you, on behalf of the Albanian population of Yugoslavia, this petition on the state of this ethnic minority and beg Your Excellency to bring it to the attention of the Members of the League of Nations:Mr Secretary General, we are not the first envoys of the Albanian population living in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia to have addressed the League of Nations concerning the lamentable state of this minority, created by Serb rule, and we will certainly not be the last to protest before this high institution of international law unless the political course taken by the rulers in Belgrade towards their Albanian subjects alters its bases and procedures.

This political course, which is already replete with excesses and misfortune, can be summed up in one phrase: To change the ethnic structure of the regions inhabited by Albanians at all costs. The strategies used to this end are as follows:

a) various forms of persecution in order to force the population to emigrate;

b) the use of violence to forcefully denationalize a defenceless population;

c) forced exile or extermination of all people who refuse to leave the country or to submit peacefully to Serbification.These three strategies correspond to three categories of oppression:

The victims of the first category are the over one hundred forty thousand Albanians who have been forced to leave their homes and belongings and to emigrate to Turkey, Albania and other neighbouring countries, anywhere they can find shelter, a bit of food and a little more human kindness.

The second category includes the population of 800,000 to 1,000,000 Albanians, Moslems for the most part, who live in compact settlements along the border to the Kingdom of Albania up to a line including Podgorica, Berana and Jenibazar in the north, the tributaries of the Morava river in the northwest and the course of the Vardar river in the south.

The last category includes the ever increasing number of Albanian figures in Yugoslavia who have been banned from the country because of their patriotic sentiments and the long list of obituaries of those who have paid with their lives for their opposition to denationalization, the most recent victim of which is our brother in Jesus Christ, the reverend Franciscan Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi, trapped by the gendarmes in an ambush and assassinated on 14 October last.

Excellency,

In order to be spared the fate of our esteemed advisor and friend Gjeçovi, we have been forced to abandon our homes and our sacred ministry on behalf of our grieving and wretched compatriots. Our main concern is to make known to the League of Nations and to the civilized world the suffering of our brethren living under Yugoslav oppression.

Condemned by misfortune to pass from one yoke to another, this part of the Albanian nation, no less important in numbers than that in the independent state of Albania, has not, for one single moment over the past centuries, known the benefits of liberty. The right to self-determination, proclaimed by the founder of the League of Nations, an apostle of international peace, remains our sacred aspiration. Indeed the League of Nations, which has set as its basic goal the elimination of the grounds of conflict between states, has also endeavoured, by means of Treaties on Minorities, to prevent the causes of misunderstanding between states and their subjects belonging to other races, language groups and religions.

The stipulations of these Treaties, solemnly agreed to by the Governments, have allayed many fears and, in particular, given rise to many expectations for peoples who are obliged to live under foreign rule. One of the most numerous of these peoples is, without a doubt, the Albanian minority in Yugoslavia. It finds itself in the sad situation of having to realize, more than many other similarly ruled populations, just how deceitful Governments can be, which, on the one hand collaborate in the work of the League of Nations, but on the other hand, do everything they can to avoid applying the conventions concerning them to which they have voluntarily adhered. This is precisely the case of the stipulations concerning minorities contained in the Treaty of Saint Germain-en-Laye, signed by the Serb-Croat-Slovene (SHS) State on 10 September 1919. None of the benefits stipulated in the Treaty has been accorded to the Albanian minority in this country, from the protection of life and property to freedom of movement, as will be demonstrated in the appendices to follow. These stipulations have remained a dead letter, in particular those by which the Treaty, inspired by the loftiest of intentions for peace and humanity, has endeavoured to provide minorities with rights to resist forced denationalization. Eager to avail itself of the property deeds of the inhabitants of these ethnically Albanian regions, the Yugoslav Government makes nothing of the rights which the League of Nations has endeavoured to give our minority, and, what is more, shows no scruples whatsoever in its choice of means to attain its objective.

Excellency,

We come to protest, not out of animosity towards Yugoslav rule or towards any unjust treaties to which we have been forced to submit, but because of persecution deriving precisely from the violation of just treaties. Convinced that the League of Nations will not tolerate the systematic violation of the Treaty, the implementation of which it guarantees, the Albanian population of Yugoslavia, Moslems and Christians together, submit to the League their complaints in the profound conviction that they enjoy its protection.

Convinced that the esteemed League of Nations will willingly take our complaints into consideration, we also venture to draw its attention to measures conducive to alleviating the situation, which is becoming more and more intolerable every day and about which the Albanian minority raises its voice in protest. In our humble estimation, it would be very useful to send a commission of inquiry to check up from time to time on compliance with the Treaty on Minorities. Much more effective for ensuring its application, however, would be the setting up by the League of Nations of a Commission or the seconding of a Permanent Commissioner to reside in one of the towns in the minority region. An uninterrupted control would force the pledges taken to be respected, and would have a twofold advantage. Firstly, its vigilance would put an end to the ambiguous reports prepared by governments which refute the complaints made by the minorities and present a totally different situation to the League of Nations than that really existing. This is the case, for example, in the most recent Yugoslav document about the Albanian minority (No. C. 370 of 26 August 1929) in which it is stated that there are 'schools' in our region and that the Committee charged with investigating the matter is satisfied, believing these to be schools in which Albanian is taught. In reality, eight thousand Albanians do not have a single elementary school, just as they do not occupy a single post of importance in public administration. Secondly, the zeal with which the denationalization campaign is being waged would be moderated by the presence of the said Commissioner, and the various acts of violence and persecution could be eliminated to a large extent. In short, the watchful eye of the League of Nations would lead to an effective implementation of the treaties and to a normalization of relations between the rulers and the ruled.

Please be assured, Mr Secretary General, of our unshakable faith in the mission of the League of Nations and of the high esteem in which we hold Your Excellency.

Geneva, 5 May 1930

Signed:

Dom Jean Bisak

Dom Etienne Kurti

Dom Louis Gashi

List of Appendices

DocumentationIn the following appendices, we have endeavoured to demonstrate with precise facts the truth of the claims we have had the honour to include in this memorandum. The events referred to are given as examples only and have been chosen at random from a multitude of similar cases. To be as clear as possible, we have made reference to the provisions of the Treaty on Minorities signed by the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and followed them by the facts which prove that these provisions have not been applied with regard to the Albanian minority.

The facts speak for themselves. Their authenticity cannot be denied, even in the knowledge that an official inquiry is impossible.

APPENDIX 1 - PROTECTION OF LIFE

I

The beginning of Serb rule

Our calvary began in 1912. Inquiry of the Carnegie Endowment. ReferencesII

Mass extermination

1. Localities of grief

2. The Dubnica massacre

3. A village wiped out for an offence of which it was innocentIII

Crimes attributed to the agents of the authorities

Ten crimes in six months in one subprefecture aloneIV

The assassination of the Franciscan Father Gjeçovi

A forerunner of Father Gjeçovi. The figure of Father Gjeçovi. A valued ethnographer. He was active in Yugoslavia as a missionary and as a scholar. Summoned to appear before the authorities, he was waylaid and murdered. Numerous witnesses but no testimony. A derailed inquiryAPPENDIX 2 - PROTECTION OF LIBERTY

I

The case of the authors of this memorandum

1. Chauvinist absurdities. "There is no room for Albanians in Yugoslavia." Refugees for life

2. Letter addressed to H.E. the Apostolic Nuncio in Belgrade. The assassination of Father Gjeçovi is "only the beginning". Reports on sermons. Personae non gratae in our own country. Why we were forced to abandon our country and our belongingsII

Forced emigration

1. Emigration is due to persecution

2. The means used to encourage emigration

3. Emigration to Albania

4. Emigration to Turkey

5. Plundering of the emigrants

6. Albanians are forced to emigrate in order that Montenegrins and Bosnians can settle their landIII

Various restrictions on personal freedom

1. Imprisonment, searches, requisitions

2. Censured clothing

3. Freedom of movement

4. Forced labourAPPENDIX 3 - RIGHT TO PROPERTY

1. Forms of seizures

2. Confiscations and expropriations

3. Confiscation of public property

4. The agrarian reform

5. CompensationAPPENDIX 4 - CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS

1. Being of Albanian origin is an impediment

2. The Albanians have been excluded from municipal functions

3. Justice is not impartial

4. Arbitrary taxation

5. Political rights are non-existentAPPENDIX 5 - USE OF THE NATIONAL LANGUAGE

1. The Albanian language has been persecuted more than any other in the Balkans

2. Restrictions continue for Albanians in YugoslaviaAPPENDIX 6 - SCHOOLS AND PRIVATE CHARITIES

1. The Yugoslav Government has banned Albanian private schools

2. Albanians are permitted no intellectual activity

3. Even religion may not be taught in AlbanianAPPENDIX 7 - PUBLIC EDUCATION

1. The view of the committee set up by the League of Nations to examine the issue of minority education

2. The Albanians are not oblivious to the benefits of schooling

3. Teaching staffAPPENDIX 8 - PRIVATE PIOUS FOUNDATIONS

1. The Yugoslav Government confiscates the property of pious and charitable foundations

2. The pious foundations of Albanian Christians have been plundered, too

3. Not even cemeteries have been exempted

4. Difficulties involving burials

APPENDIX 1

PROTECTION OF LIFE"The SHS State pledges to accord full and complete protection of life and liberty

to all inhabitants irrespective of birth, nationality, language, race or religion."

(Treaty on Minorities, Article 2)I The beginning of Serb rule

With regard to the protection of the life and liberty of the Albanian population living within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, one could write volumes on end if one were to refer to all the instances in which this protection has been intentionally withheld.

The calvary of our people begins with the arrival of the 'liberating' Serb armies in 1912 in regions inhabited by an Albanian majority. The consequences of the conquest of this country were noted as follows in the appalling conclusions reached by the Commission of Inquiry set up by the Carnegie Endowment:

"Houses and villages set on fire, mass murder of an unarmed, innocent population, unspeakable violence, plundering and all sorts of brutality - such are the means which have been and are being used by Serb and Montenegrin troops with the aim of altering the ethnic structure of regions inhabited exclusively by Albanians."

Nonetheless, it is not our intention to chronicle the events which took place before the signature of the Treaty on Minorities. Those wishing to know more about them may consult the press of the period in question as well as specialized publications in which they will find a record of many of the atrocities committed, including names, dates and places.

II Mass Extermination

1. Localities of grief

Prishtina, Mitrovica, Junik, Shtima / Shtimlje and Vrella / Vrela are names of localities calling to memory bloody events, mass murders committed for no purpose against an innocent population whose only crime was to be of Albanian nationality.

2. The Dubnica massacre

On 10 February 1924, in Dubnica, District of Vuçitërna / Vucitrn, the village was encircled and then set on fire on the orders of the prefect Lukic and of the commander Petrovic so that all the inhabitants would be burnt alive. Their crime had been the following: The gendarmes wanted to capture a bandit called Mehmet Konjuhi but had not succeeded. The bandit having escaped, the authorities laid the blame not only on the relatives of Mehmet Konjuhi, who were all massacred, but on the entire village. Twenty-five persons, including ten women, eight children under the age of eight, and six men over the age of fifty, died in the fire. No one was punished for this crime.

3. A village wiped out for an offence of which it was innocent

Bandits killed a gendarme in the region of Rugova. Colonel Radovan Radovanovic was sent to investigate the case. Not being able to find the culprit, the colonel encircled the village closest to the place where the gendarme had been slain and set it on fire. We do not know how many people died.

III Crimes and offences attributed to the agents of the authorities

The number of crimes committed sporadically by those supposed to protect and guarantee the lives of citizens is much higher than that resulting from the mass murders. In order to convey an idea of the numbers involved, we provide the following table for one subprefecture alone, that of Reka, District of Dibër / Debar, for a period of six months.

Name and locality

of the victims

_____________Name and office

of the perpetrator

_____________Date of the crime

_____________Observations

_____________1. Islam Zhuli

of ZhuzhnaCorp. Cedomir

of the Tanush /

Tanuš policeNovember 1928

The victim was

summoned on

the pretext of

a job and was

slain on his way2. Mexhid Bekiri

of BogdaCorp. Markovic

of the police

in JerodovicNovember 1928

3. Veli Boga

of Bogda2nd police Lieut.

Rada TerzicNovember 1928

Slain on pretext

of cowardice4. Ismaili and

Lazimi, both

of OrguciPopovic and

Markovic of

the Ternic police10 Dec. 1928

Slain on their

way to market

in Gostivar5. Musli Bajrami,

mayor of SencaCorp. Markovic

of the Ternic policeJune 1929

Slain in front

of his house6. Jakup Ibrahimi

of NivishtaOfficer Niko

Milanovic and

a companion of

the Tanush /

Tanuš police5 July 1929

Slain in the

presence of

his brother on

his way back from

Gostivar market7. Zeqir Ismaili

of PresenicaSerg. Kaprivic

of the Reka15 July 1929

One-time mayor

8. Zurap Fazlia

of NicpurSerg. Lazovic

of the Mishrova /

Mišrovo police15 July 1929

Slain in front

of his house9. Rakip Muhtari

of GrekAn agent of

the subprefecture18 July 1929

Released by the

police after two

days of arrest and

slain near the

church in BekaIV The assassination of the Franciscan Father Gjeçovi

The Franciscan Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi Kryeziu was assassinated on 14 October 1929 under circumstances which leave little doubt as to the motives of the crime.

Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi is unfortunately not the first Albanian Franciscan to have fallen as a martyr for his patriotic sentiments and his faith. The first was Father Luigj Palici who was summoned by soldiers under the command of a bandit dressed as an Orthodox priest and was ordered to renounce his Catholic faith publicly in favour of the Eastern Orthodox faith. He refused energetically and was maimed with the butt-ends of the soldiers' rifles and then stabbed to death with a bayonet. This took place in Gjakova / Djakovica on 7 March 1913.

Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi, for his part, was slain because of his stance as a good Christian and as a man devoted to justice and knowledge.

Born in 1874 in Janjeva / Janjevo in the District of Prishtina, now part of Yugoslavia, Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi opted for Albanian nationality despite the inconveniences this caused him during his stay on Yugoslav territory. After having finished his studies in philosophy and theology, he carried out his mission in Albania for many years and was held in high esteem by all those who came to know him. Devoted to the study of ethnography, he was the first person to bring to light a very important work on Albanian customary law, the Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini. He was much praised for this publication and received the title of doctor honoris causa from the University of Leipzig.

As a great admirer of the chivalrous customs of his people, he had long since begun an in-depth study on Albanian folklore, for which he had travelled widely throughout Albania. He had recently taken up duty, in continuation of his spiritual mission, in the village of Zym amongst the Albanians of Yugoslavia.

Zym, in the District of Prizren, Yugoslavia, is an Albanian village of one hundred twenty houses, of which one hundred houses are inhabited by Catholics and twenty by Moslems. In view of the nationality of the inhabitants, the Government only set up a school in this locality in 1926. One must not suppose, however, that teaching in Albanian, the mother tongue of the inhabitants, was permitted. The Government nominated to the post of teacher a Serb who, being Orthodox, trod on the religious sentiments of the pupils. Father Gjeçovi, of his own will, taught the children the catechism in Albanian and for this reason was not on good speaking terms with the Serb teacher who called him an 'Albanian nationalist'.

What is more, the Serb chauvinists regarded his research in the field of folklore as political propaganda. This was enough to bring about his downfall. Father Gjeçovi had on many occasions sensed the hostility of the Yugoslav authorities and of the members of the chauvinist association Narodna Odbrana, which terrorized the Albanian population throughout Yugoslavia quite openly. But he could not imagine that they would go so far as to take his life because of his views. Realizing that no favourable circumstances were at hand to do away with him without causing suspicion, their hired assassins resorted to the following infallible method.

Two gendarmes, probably attached to the police station near the village of Zym, approached Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi on 13 October last to notify him that he had been summoned by the subprefect of Prizren and was to appear before him as soon as possible. Surprised by this order, Father Gjeçovi suspected something was afoot and was unwilling to depart alone. He therefore took with him a school employee and a guard from the municipal hall. On his arrival in Prizren, he first paid a visit to the Bishop, to inform the latter that he had been summoned by the subprefect. He then reported to the subprefect, who expressed his astonishment and declared that he had not issued any order to summon the priest. Father Gjeçovi's original suspicions had now become more concrete. He returned to the Bishop to inform the latter of what had taken place during his talk with the subprefect and set off for home, still accompanied by the two gentlemen. At a point along the road, not far from the village, they noticed two armed men approaching, who, after cursing the Reverand Father, fired on him. Gjeçovi was felled by the first shot. The bandits, to make sure of their deed, then advanced and riddled him with bullets.

It must be noted that on the road, in the immediate vicinity of the crime, there were numerous workers carrying out road-repairs. Also present were the two companions of the victim. The police station was not far off either. Despite all the witnesses, the assassins got away with their crime and departed in no hurry, like individuals who had finished their work and had nothing to fear. And they indeed had nothing to fear. The inquiry produced no results and never will produce any results, because this does not seem to be its purpose. On the contrary, attempts have been made to use the inquiry in order to stain the reputation of the victim and to step up the persecution of the Albanians. Despite all the evidence, they are endeavouring to camouflage the political character of the crime, which is nonetheless conclusive, given the history and circumstances of the crime and the satisfaction the assassination caused in Serbian nationalist circles. One of these people, a police officer, mocking the profound grief which the loss caused to the authors of this petition, alluded menacingly that Father Gjeçovi had received his just deserts and that the same fate awaited all of us with him.

APPENDIX 2

PROTECTION OF LIBERTY(Concluded after the treaty on the protection of minorities had been signed)

(Treaty on Minorities, Article 2 et seq.)I The case of the authors of this memorandum

(The priests Gjon Bisaku, Shtjefën Kurti and Luigj Gashi)

1. Chauvinist absurdities

We have been obliged to abandon our country because of ever-growing restrictions to our freedom of speech, of movement and of access to our parishioners, etc. All our movements and all our actions were suspect to the authorities simply because we refused to become Serb 'patriots' and serve the goals of the terrorist organization Narodna Odbrana, i. e. preaching to our compatriots the absurd idea of the Serb chauvinists that we should consider ourselves Albanized Serbs and consequently should not pray to God in Albanian or teach our children their mother tongue.

Our disobedience, considered a grave menace to the interests of the state, was not to be forgotten or pardoned. No longer able to tolerate the accusations and threats, we abandoned our parishes last December to seek the aid and protection of the central authorities in Belgrade. The Ministry of the Interior gave us the standard formal assurances, but did not regard our complaints as important. On the contrary, it would seem that our complaints, instead of calming relations, made the hostility of the authorities even more acute. As soon as we arrived in Skopje, we were informed that the police were looking for us and wanted to arrest us. We were reminded of the threat of one of the police officers who had told us, "There is no room for Albanians in Yugoslavia. The Gjeçovi affair is only the beginning - your turn will come." It was at this point that we decided to leave everything behind to save our lives and our honour.

As there was no question of us obtaining passports to get to Rome to the Sacred Congregation of the Propaganda Fide under whose orders we were working as missionaries, we were forced to leave for the Albanian border, confronting all the dangers inherent in such a crossing, in the hope of saving our lives in exchange for leaving behind everything: our country, our families and our possessions.

2. Letter addressed to H.E. the Apostolic Nuncio in Belgrade before our departure

Most Illustrious and Reverend Excellency,

It is with profound grief that we have abandoned our families and friends and, most of all, our wretched people who enjoyed some small consolation from the fact that we had remained with them and shared their sufferings.

We would like to submit to Your Excellency a summary of the reasons for our departure. Our situation and our stay in the District of Gjakova / Djakovica has become futile and impossible over the last few years. The situation is becoming worse from year to year, and now the worst has happened - the assassination of Father Shtjefën Gjeçovi on 14 October 1929. Why? Who killed him? We leave it to others to judge, since Your Excellency is in possession of precise documents. What worries us most are the rumours and the statements made by police officers, such as the captain of the gendarmes in Prizren, who said, "This is only the beginning." The commander of the gendarmes in Peja / Pec, Popovic said to one of us sneeringly, "Your turn will come!" Another officer, Zarko Andjelkovic boasted, "We killed Father Gjeçovi and now we are going to kill the priest in Peja / Pec." The Serbs we know warned us to be on our guard. Why? What had we done? They even ask us to submit summaries of our sermons at church, etc. One of us was told that he was a member of the Kosovo Committee of Shkodër, and another was accused of having built a church with foreign money, etc. In short, we have become 'personae non gratae' and are no longer welcome. The fact that we are 'personae non gratae' in the eyes of the government was confirmed Wednesday evening by our bishop at a meeting with the two deaneries of Peja / Pec and Gjakova / Djakovica when, talking to Father Ljubomir Galic, the latter told him it was true, adding that no priests could be found for these parishes.

Under such circumstances, what else could we do?

It would seem futile for us to remain there to be killed, not for our religion but because of base allegations such as those made against the late Father Gjeçovi, all the more so since we put no store in acts of blind heroism. Whether we remained or departed, our parishes would have been deprived of their priests in any case. We informed the bishop as much on several occasions. In order to save our lives, we now find ourselves compelled, against our will, to abandon our diocese, our parishes and our wretched but beloved people, not to mention our possessions.

We beg Your Most Illustrious and Reverend Excellency to contact the Sacred Congregation of the Propaganda Fide, whose servants we are, to request another mission in which we will be able to carry on with our sacrosanct ministries as priests, and to arrange that we be sent back to the Sacred Congregation to which we shall expose our trials and tribulations and our needs and to which we offer unconditional obedience. We would beg you to do this as quickly as possible since we have lost everything, are in the midst of our journey and are apprehensive that we may be followed and arrested.

In the hope that Your Excellency will have the kindness to take the above into consideration and to come to our assistance, we remain your very humble and devoted sons,

signed,

Dom Gjon Bisaku, Dom Luigj Gashi, Dom Shtjefën Kurti

Belgrade, 14 December 1929II Forced emigration

1. Emigration is due to persecution

Before the Serbian occupation, emigration was unknown among the Albanian population living in the regions now under Yugoslav rule. It is true that workers went abroad temporarily to neighbouring countries, but never with their families.

The mass emigration which has occurred since 1912 is due without a doubt to the various kinds of persecution which make life impossible for the poor people and force them to abandon their homes.

2. The means used to encourage emigration

The means used by the Yugoslav authorities to force the Albanian population to leave the country are numerous. Death threats, restrictions on their freedoms in all areas of life, expropriation without compensation, house searches and frequent raids and arrests for no plausible reason, as well as a ban on teaching their national language and on expressing patriotic sentiments other than those desired by Serb nationalists. These means are utilized on a daily basis. These oppressive measures are carried out in good part by chauvinist associations such as the Narodna Odbrana.

3. Emigration to Albania

At the present, there are about ten thousand refugees pretty well throughout Albania and they are in a miserable state. The Albanian Government seems to have made a laudable effort to shelter these refugees, but there can be no doubt that its good will alone will not be enough to receive and take care of all those still wishing to come. Consequently, it has been obliged to refuse entry visas for most of them. They have therefore taken refuge further afield, principally in Turkey.

4. Emigration to Turkey

The number of emigrants in Turkey surpasses the figure of 130,000. The Turkish Government has taken advantage of these people to populate regions in Anatolia which are more or less deserted, but where a good number of them have perished because of the climate and deprivation. This exodus does not seem likely to end unless the persecution which has given rise to it is brought to an end. Two hundred Albanian families have recently left for Turkey. But the matter does not stop here. In its desire to get rid of the Albanians, the Government in Belgrade has initiated talks with the Government in Ankara on the transfer to Turkey of three to four hundred thousand Albanian Moslems from Kosovo. If nothing has yet come of the project, it is no doubt due to the influence of the League of Nations and to world public opinon which would have raised an outcry.

5. Plundering of the emigrants

To encourage emigration to Turkey, the Yugoslav authorities provide certain favourable conditions such as the following. A young man of Albanian origin doing his military service is discharged early so as to be able to accompany his parents forced into emigration.

Emigration to Albania is not well looked upon. The Yugoslav Government has every interest in ensuring that these persecuted and dispossessed refugees settle farther away from its borders. As such, a thousand obstacles are put in the way of the wretched individuals wanting to be reunited with their families in Albania. A host of public employees and lawyers are only waiting for a chance to put the final touches on the misery of these poor people. To obtain passports, they are harassed and plagued until they agree to pay exorbitant sums, four or five thousand dinars, which often amount to their total savings.

The following are the most recent cases of inhuman exploitation we learned about before our departure:

a) A Moslem Albanian peasant from the village of Leshan / Lešane in the District of Peja / Pec was forced to pay 6,000 dinars to the Serb lawyer Zonic in Peja / Pec as a passport tax.

b) The Serb lawyer Ljuba Vuksanovic of Peja / Pec demanded 8,000 dinars of another Albanian peasant to obtain a passport for him because the "procedure was extremely difficult."

c) A Catholic Albanian from Skopje by the name of Geg Mata who had emigrated to Albania could only obtain a passport for his wife and son after five months of harassment and the payment of 2,000 dinars in bribes.

It must be noted in this connection that the normal passport tax is no more than fifty dinars.

6. Albanians are forced to emigrate in order that Montenegrins and Bosnians can settle their land

Montenegrins and Bosnians from Srema and the Banat are invited to settle in the villages and live in the expropriated and confiscated homes of the Albanian refugees with the obvious purpose of changing the ethnic structure of the region. Such resettlements of people have occurred pretty well everywhere and the campaign is continuing with an ever-increasing intensity. We refer, as examples, to the following localities:

a) In the District of Gjakova / Djakovica: the villages of Lugbunari, Piskota, Dubrava, Mali i Ereçit, Dashinoci, Mali i Vogël, Fusha Tyrbes, Beteshet e Marmullit, Neci etc., etc.

b) In the District of Peja / Pec: Fusha e Isniqit / Istinic, Turjaka, Fusha e Krushecit, Malet e Leshanit, Krusheva, Vitomirica, etc., etc.

c) In the District of Prizren: Fshaja, Gradisha, Xërxa / Zrze, Lapova / Lapovo etc., etc.

It has also happened that inhabitants of Albanian origin who left their homes temporarily returned to find Serbs living in them who had been granted absolute title to them by the authorities.

III Various restrictions on personal freedom

1. Imprisonment, searches, requisitions

Reference must be made first and foremost to the arrests and imprisonments which, in addition to house searches and various requisitions, constitute the most effective means utilized by the government authorities to harass the Albanian population. Any charge made against an Albanian leads to his immediate arrest, whether or not the accusation is true and the source is reliable. Charges usually arise from quarrels between individuals. They are often instigated by provocateurs and sometimes invented by government officials. An innocent allegation is often sufficient to turn the general climate of suspicion against the Albanian population into one of certainty that crimes have been committed, thus setting off a series of harsh measures against innocent individuals. There are numerous cases. They happen almost every day. Let us confine ourselves to a few recent examples:

a) Hafëz Hilmi and Shukri Dogani, who until recently were mayors of localities in the Kaçanik / Kacanik area of the District of Skopje, were not on good speaking terms with the local authorities and were accused of collaboration in a 'Kosovo Committee' which exists only in the troubled imagination of Serb chauvinists. The above-mentioned men were imprisoned on the basis of this supposition.

b) The merchant Mulla Rifati, born in the same region, was arrested on a similar charge.

c) Sherif Gjinovci, a person well-known to the Albanian community in Yugoslavia, was arrested six months ago and accused of intervening in a feud between two feuding Albanian families.

2. Clothing

In its violent actions aimed at the 'ethnic unification' of the state, the Belgrade Government also does its utmost to eliminate differences in clothing that give an indication of nationality in this part of the kingdom. In some places, such as Reka, where Orthodox Albanians live together with Slavs of the same religion and with Moslem Albanians, the differences are limited to various types of headgear. The Albanians wear the kësula whereas the Serbs wear the cajkac. To do away with this shocking distinction, Mr Sokolovic, the subprefect, issued an order to all police stations in his region last May forbidding Albanian peasants from wearing the kësula. They are now forced to don the Serb cap. The police were only waiting for a pretext to tear up the Albanian caps.

3. Freedom of movement

Another form of persecution is limiting freedom of movement. In many regions, the Albanians are not allowed to leave their villages without notifying the authorities beforehand. In order to visit a relative from another village, to go to a fair to sell produce or to travel to market to go shopping, i.e. any circumstances involving a departure from one's native village, one must notify the chief of police. This form of persecution increased substantially last year in the District of Dibër / Debar.

It goes without saying that the authorities do not provide any prompt or satisfactory services unless the peasant accompanies his request with a bribe.

4. Forced labour

Serbs and Albanians of the region in question are employed in the construction and repair of national and local roads and in other public works. As to their treatment, a distinction is made. The Serbs are regularly paid as labourers whereas the Albanians are quite often not paid at all, or receive very little. In addition, they are obliged to provide their own tools and workhorses or oxen without recompense.

APPENDIX 3

THE RIGHT TO PROPERTY"Persons having chosen another nationality will be at liberty

to keep their immovables in the territory of the SHS State.

They will be free to bring their goods and chattels of all kind with them"

(Treaty on Minorities, Article 3)It is true that this article is more specifically aimed at those who choose Austrian, Hungarian or Bulgarian nationality, but in view of the general character of the treaty which is designed to protect all minorities, one can conclude that the regulations regarding the right to property, which conform by the way to common law existing in most countries, are also applicable to Albanians who have become nationals of the State of Albania, of another country or who have remained Yugoslav subjects.

1. Forms of seizures

In reality, quite different measure are applied to the Albanians. Pure and simple expropriation without any compensation is one of the most common and efficient means of forcing the Albanians into exile. Confiscation of property is practised against our people on a vast scale. In addition to this is the agrarian reform, a package of government measures which was never passed by parliament, but which the authorities nonetheless utilize in their own fashion, depending on the persons in question.

2. Confiscations and expropriations

The confiscation of property is carried out against persons who are absent and against all Albanians inhabitants whose Serbian patriotism is considered doubtful. As to formal charges, there is no need for them whatsoever. Any accusation by a Serb against an Albanian is tantamount to condemnation. Should there be need of further witnesses, members of the Narodna Odbrana and the Bela Ruka (White Hand) are always ready to serve the nation.

It would be impossible here to list all the cases of unjust confiscations we are aware of. We do wish, however, to cite a few examples in one specific region.

a) The following persons from the District of Peja / Pec had their property confiscated without explanation: Jusuf Arifi of the village of Bec, Grosh Halili of the village of Turjaka, Tahir Bala of the village of Papiq, Bajram Sula of the village of Krestovec, and Memdu Bey, whose property was estimated at over 2,000 hectares.

b) Most rich Albanian families have had their property confiscated to demoralize them, deprive them of political influence and oblige them to submit to the Yugoslav yoke without protesting. Here are a few examples from the District of Gjakova / Djakovica alone: Asllan and Kurt Bey Berisha, Ibrahim Bey, Ismet Bey Kryeziu, Ahmet Bey Berisha, Poloska, Halit Bakalli, Muhamet Pula, Prenk Gjoka, Mark Nikoll Biba of Brekoc, Muftar Dema of Zhub / Žub, Bek Hyseni of Zhub / Žub, Gjon Marku of Guska, Gjon Doda of Pllangçora.

3. Confiscation of public property

Confiscations and expropriations have affected not only individuals but also collective groups. Albanian villages have been dispossessed of their farm and pasture land pretty well everywhere. Here are a few examples:

a) In the District of Gjakova / Djakovica: Marmull, Rezina, Brodesana, Doblibarja, Meçeja, Cërmjan / Crmljan, Kryelan, Bardhaniq, Dashinoc, Lumëbardha, Lluga, Qerim, Lugbunar, Trakaniq, Novosella / Novoselo, Bec, Palabardh, Gergoc, Dobrigja, Firaja, Gramoçel, Fusha e Kronit të Plakës (Piskota), Babajt e Lloçit, Deçan / Decani, Lloçan, Voksh, Kallavaja e Junikut, Batusha, Rracaj, Pacaj, Pllangçora, Dujaka, Hereç, Ponashec, Brovina, Nec, Babajt e Bokës, Koronica, Mejeja, Guska, Fusha e Tyrbes, Brekoc, Vogova, Zhub / Žub, Firza, Moglica, Rraç, Pjetërshan, Kusar, Dol, Kushavec.

b) Other examples from the District of Peja / Pec: Isniq / Istinic, Strellc / Streoc, Fusha, Pishtan, Baran / Barane, Leshan / Lešane and all the pasture land down to the Drin river and from there to Gjurakovc / Djurakovac, Rakosh / Rakoš, Ujmirë / Dobra Voda, and Rudnik.

The situation is similar in other regions inhabited by Albanians.

4. The agrarian reform

Far more numerous are the victims of the so-called agrarian reform, which was applied with extreme rigour to the Albanian population. Under the reform, citizens having completed their military service are entitled to 5 hectares of arable land per person. Albanian families, which still maintain a patriarchal structure and include six to ten adult males, would accordingly have the right to thirty to fifty hectares of land. At the present moment, there is not a single farming family in all of Yugoslavia owning such a spread of land. Even properties of one hectare have been expropriated.

Here are a few examples which prove that the agrarian reform is nothing more than a pretext for plundering and inhumanity:

a) Mark Vorfi, from the village of Fshaj in the District of Prizren, and his four brothers together owned ten hectares of land. The expropriation took everything away from them.

b) Aleksandër Shaupi of the same village owned fifteen hectares of land. He has five brothers and, according to the law, would normally have a right to at least thirty hectares. At the present moment, they do not have a single hectare left.

c) Jup Pozhegu of Gjakova / Djakovica owned eight hectares of land in the village of Bishtazhin (District of Prizren). All he has left at the moment is one square meter.

d) In the autumn of 1929, twenty-six Albanian families from Rugova, District of Peja / Pec, were expelled from their homes and deprived of their possessions, and were forced to seek refuge with friends. They were forced to go begging in order to survive.

5. Compensation

For two years, a compensation of 5% of the value of the property expropriated was offered in some regions to the dispossessed, but only to those persons well regarded by the authorities. Aside from this initial compensation, expropriated Albanian landowners have received nothing at all.

APPENDIX 4

CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS"Complete equality (for all minorities) to enjoy civil and political rights,

notably to accept public office, functions and honours".

(Treaty on Minorities, Article 7)1. Being of Albanian origin is an impediment

This stipulation in the Treaty has not been applied at all with regard to the Albanian population in Yugoslavia. Albanians, in particular those who have studied at universities abroad, no longer even try to obtain functions or jobs in the public service since they are aware from the start that the main condition for employment is not the qualification of the applicant, but rather nationality. This condition is of course not legally binding, but is strictly respected by those who are authorized to apply it. This explains the startling fact that a population of eight hundred thousand people is not represented in the public service by one single official of any importance, i. e. a prefect or subprefect. If some minor employees have been given jobs, they got them most certainly by being servile or sycophantic, whether because of their abject poverty or because they were lacking in morals.

2. The Albanians have been excluded from municipal functions

The same condition exists for employment in the municipal administration, even though the local authorities were elected by the public. The Albanians are excluded from public office. Mayors who were formerly elected are now appointed directly by the Government. Municipal offices are organized in such a way as to keep representatives of the Albanian majority out of the administration. In more populated localities which have a municipal administration of their own and in which a Serb population also exists, albeit as a minority, municipal councils are still composed for the most part of Serbs. In grouping together small villages to form a municipality, great care is taken to include one Serb village with the four or five Albanian villages, with the sole purpose of keeping the Albanians out of the administration. Where such measures cannot be implemented, a Serb adviser is appointed to work with the mayor in question and, in actual fact, becomes head of the municipality himself.

Here are a few examples of the foregoing:

a) In Peja / Pec, where the vast majority of the population is Albanian, the former mayor Nexhi Basha, an Albanian, was replaced by a Montenegrin called Maja who is hardly known at all to the population.

b) The former mayor of Gjakova / Djakovica, Qazim Curri, who is of Albanian origin, found himself with a Serbian office administrator who took over all the decision-making.

c) In Prizren, where there is also a large Albanian majority, there has not been one single Albanian mayor of a town or municipality since the Serb occupation of the country began.

d) In Vogova, District of Gjakova / Djakovica, the mayor was an Albanian called Marc Ndou. He was replaced by a Montenegrin, Milan Popovic, a bandit and thief who was subsequently convicted for his crimes. In subsequent elections, Ndre Bib Doda was voted in as major, but was nonetheless ousted and replaced by Radovan Popovic, cousin of the above Milan Popovic, who was no less notorious than his cousin as an implacable enemy of the Albanian population.

The same can be said of the municipalities of Ponashec, Deçan / Decani, and Irziniq etc., all in the riding of Gjakova. The situation is no different in other regions.

3. Justice is not impartial

As to justice, the Albanian population is poorly served since it has no legal recourse against a Serb.

Thousands of examples have proven to the Albanians that they have no chance whatsoever of winning a case in court. They can only repeat the popular wisdom that laws made and applied by a ruler are not to the advantage of his subjects. With this in mind, Albanians in Yugoslavia rarely go to court, not wishing to add more financial loss to the injustice they have incurred.

Here are a few examples:

a) Myftar Dema, of the village of Vogova in the District of Gjakova / Djakovica, accused the mayor, Milan Popovic, of embezzling 20,000 dinars belonging to the municipal authorities. The latter was indeed tried and imprisoned. But after one month in prison, he was released and given free rein to torment his accuser.

b) A Serb called Krstic, together with his accomplices, killed sixty Moslem Albanians from Jabllanica / Jablanica (District of Gjakova / Djakovica) in one day, among whom was the influential Osman Aga Rashkovi. The family of the latter had the culprit brought to trial. In order to save him, despite the overwhelming evidence of his guilt, the authorities declared him to be deceased, even though Krstic is still alive and well and now living in Istog / Istok in the District of Peja / Pec.

c) In the midst of an interrogation in the subprefecture of Gjakova / Djakovica, an Albanian, Lazër Dreni, was struck down with the butt of a fire arm by an employee of the subprefecture, Jovan Milic, in the presence of the secretary Djulakovic. Milic was imprisoned for several hours for form's sake and then released.

4. Arbitrary taxation

Arbitrary taxation measures are quite often applied to the Albanians. The taxpayer is not in a position to know exactly how much he will have to pay in taxes in a given year. He is normally at the mercy of tax officials who make him pay double or triple of what he is legally bound to pay.

Before the beginning of the dictatorship, over half the seats on the thirty-six-member tax commissions in Kosovo were occupied by Albanians. At present, their representation has been reduced to two. The other thirty-four members are Serbs.

5. Political rights are non-existent

As is evident from the above, the political rights of citizens of Albanian origin simply do not exist. The Albanians hoped for one moment in 1925-1926 that they would be as free as the other citizens of Yugoslavia to occupy political positions in the country. They were soon disappointed, however. The political party formed under the leadership of Mr Ferhat Bey Draga was to take part in the elections with a list of fourteen candidates for the Chamber. But on the day of the elections, the candidates were prevented by various means from taking part in the elections. Some were placed under house arrest in their own homes. When they protested, the authorities replied that the measure had been taken in their own interests, since otherwise their lives would have been in danger.

The attempt was not without consequences for these courageous individuals. Most of them were sentenced to jail, under various pretexts. The party chairman Ferhat Bey Draga was sentenced to four years in prison. Nazim Gafuri was wounded and subsequently slain in front of a police station in Prishtina. Ramadan Fejzullahu was convicted and several candidates had their possessions confiscated. All of them suffered.

Under such conditions, it is evident that the Albanians could no longer even think of entering the political ring, even as a national minority.

APPENDIX 5

USE OF THE NATIONAL LANGUAGE"There shall be no restrictions on the use of the national language

in the field of religion, in the press or in publications of any kind."

(Treaty on Minorities, Article 7)1. The Albanian language has been persecuted more than any other in the Balkans

Rightfully considered the fundamental characteristic of nationality in the Balkans, language has always been the main object of contention between the conservative spirit of peoples and the efforts of governments to enforce national unity in the country by more or less forcible means.

In this respect, the Albanian people have suffered more than all the other Balkan peoples. Under Ottoman rule, the Albanians were not allowed to used their language freely. Education, press and publications in Albanian were luxuries enjoyed only by Albanians living in foreign countries. Even correspondence in Albanian addressed to friends or relatives abroad could result in the imprisonment of the author. The Turks used these methods to combat the national awakening of the Albanians, whereas Greek and Slav propaganda, acting as the due heir to the Ottoman Empire, did its utmost to denationalize the Albanian Orthodox population through church and schools.

2. Restrictions continue for Albanians in Yugoslavia

This situation continues for the half of the Albanian people living under foreign rule.

A few examples will suffice to illustrate the truth of this assertion.

a) In the Albanian regions of Yugoslavia, there are signs on the town halls saying that the usage of any language other than Serbian is forbidden.

b) No newspaper, magazine or other publication in Albanian exists for the eight hundred thousand Albanians in Yugoslavia. The Belgrade Government may claim that intellectual activity is not prohibited under the law, but those who implement the law, the police and their officers, do their utmost to impede any such activity. If an Albanian were to venture to apply for authorization to publish a newspaper in Albanian, to hold an innocent public lecture in Albanian or to open a school to teach Albanian, he would not of course be punished for such an application, but would immediately be hounded by the police and the gendarmes on all sorts of charges, arrested and, in many cases, imprisoned or dispossessed.

c) One of the undersigned, Dom Shtjefën Kurti, until recently priest in the parish of Novosella / Novoselo, District of Gjakova / Djakovica, was forbidden by the principal of the Serbian school, Radovan Milutinovic, from using the Albanian language to teach village children the catechism.

d) When Albanian children from the village of Skivjan, District of Gjakova / Djakovica, brought Albanian spellers to the Serbian school they attended, the Serb principal, Mr Zonic, confiscated the books immediately and punished the children for "daring to learn a language other than that of the state."

e) Albanians are often reprimanded by telephone operators who order them to speak Serbian. If they do not comply, their calls are cut off.

APPENDIX 6

SCHOOLS AND PRIVATE CHARITIES"They (the minority) shall have, in addition, the right to found, manage and control at their own expense charitable, religious and social institutions, as well as schools and other educational facilities, with the right to make free use of their own language and to exercise their religion freely."

(Treaty on Minorities, Article 8)1. The Yugoslav Government has banned Albanian private schools

We have already seen what Albanian-language education was like under Ottoman rule. It may be noted in this connection that at the end of this rule, before the Balkan War, it was the Kosovo Albanians who rose in revolt against the Turkish regime to obtain freedom for national education. The policies of the Turkish administration in this field were continued under the Serb occupation. As the ban was not effectively enforced during the Great War, the Albanians in Yugoslavia hastened to open private schools for the teaching of their mother tongue (see below the list of such schools).

Once the Yugoslav Government was freed from the burdens of the war in 1919, one of its first actions was to close down Albanian schools. The school in Skopje was not closed until 1929, probably as a consequence of an Albanian complaint to the League of Nations about Yugoslav oppression.

2. Albanians are permitted no intellectual activity

At the same time as private schools, the Yugoslav authorities banned all social activity of an Albanian character. Intellectual, cultural and musical societies have been dissolved in Gjakova / Djakovica, Peja / Pec, Prizren, Skopje and other important towns.

3. Even religion may not be taught in Albanian

There can be no question of the free use of the Albanian language in the teaching of religion either. Orthodox Albanians from the Reka region, where they are in the majority, have been banned from using their language in church. Catholic Albanian priests from the regions of Gjakova / Djakovica, Prizren and Skopje etc. are considered agents of political propaganda if they so much as teach the catechism in Albanian. As to Moslem Albanians, they have no medresa where their religion can be taught in Albanian.

Schools have also been closed which had operated in the following towns: Plava with 50 pupils, Gucia / Gusinje with 60, Bec 45, Brodosana 50, Brovina 40, Lloçan 46, Irziniq 40, Novosella / Novoselo 48, Junik 40, Ponashec 45, Cërmjan / Crmljan 50, Zhub / Žub 48, Budisalk 70, Rakosh / Rakoš 80, Prizren 40, Skopje 73, etc.

The number of these schools and the number of pupils is not large. These are schools which were opened spontaneously in localities where an initial community organization already existed or in which the municipal administration, on top of its various obligations from the war, was able to maintain an Albanian-language school. If the regulations of the Treaty on Minorities were fully applied, the number of Albanian pupils in Yugoslavia would be no less that in Albania, given that half the Albanian population lives in Yugoslavia.

4. Table of Albanian private schools closed down by order of the Yugoslav Government

Locality

_________________Instructors

_________________No. of pupils

____________Ferizaj / Uroševac Catholic priest 50 Zym Pal Lumezi 40 Gjakova / Djakovica Jusuf Puka,

Sali Morina,

Niman Ferizi,

Ferid Imani,

Ibrahim Kolçiu,

Ibrahim Felmi,

Lush Ndoca840 Mitrovica Catholic priest 160 Prishtina 90 Vuçitërna / Vucitrn Haxhi Tafili 60 Peja / Pec Murat Jakova,

Hajdar Sheh Dula,

Abdurrahman Çavolli,

Mulla Resh Meta256 Peja / Pec Halit Kastrati,

Shaqir Çavolli,

Sadi Pejani125 Peja / Pec Shaban Kelmendi,

Pal Lumezi

etc.232 Peja / Pec Zef Maroviqi,

Pal Lumezi

etc.257 Gjurakovc / Djurakovac Mr Plakçori 221 Baran / Barane Xhevet Kelmendi 176 Zlokuçan / Zlokucane Ndue Vorfi 186 Strellc / Streoc Adem Nexhipi 175 Istog / Istok Osman Taraku 285 Prizren Lazër Lumezi 76 APPENDIX 7

PUBLIC EDUCATION"For localities in which considerable numbers of a minority population live,

the Government shall accord appropriate facilities to ensure that in elementary schools, instruction is given to the children of the minority in their own language."

(Treaty on Minorities, Article 9)1. The view of the committee set up by the League of Nations to examine the issue of minority education

In pursuing its policies of denationalization, the Yugoslav Government, having closed down the Albanian schools, replaced them with Serbian schools. In its most recent document addressed to the League of Nations, the Government stated that there were 1,401 schools in the regions inhabited by Albanians, out of which 261 schools with 545 classes were attended especially by Albanian pupils. The committee set up under a council resolution dated 25 October 1920 to examine the issue, "believed it was in a position to interpret the phrasing in the Yugoslav document as meaning that the schools in question were schools for the minority per se, in which teaching was carried out in the Albanian language, or were schools having classes fulfilling this condition. Based on this interpretation, the Committee considered the information provided in the report by the Yugoslav Government to be satisfactory."

The Committee was either misled by an ambiguous phrase or had learnt the truth and preferred to issue a warning in this form. Whatever the case may be, we must insist that there is not a single school or a single class among the 545 referred to by the Yugoslav Government in which teaching is conducted in Albanian, just as not one of the 7,565 Albanian pupils attending school is being taught in his own language.

2. The Albanians are not oblivious to the benefits of schooling

The number of these pupils, notes the Yugoslav Government, is very low due to the particular living conditions of the Albanians who inhabit small settlements in isolated mountain regions and show no understanding of the benefits of schooling. We have no intention of arguing with the Yugoslav Government, but cannot pass over such an accusation without demonstrating how baseless it is. Not even one third of the Albanians in Yugoslavia live in 'isolated' mountain regions. This might be stated more reasonably of the Albanians in the Kingdom of Albania. Despite communications difficulties and the smaller amount of funds earmarked for public education in Albania, the percentage of pupils is not less there than it is in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. This goes to show that the Albanians are by no means oblivious to the benefits of schooling, but only, of course, in places where schools provide real educational benefits and do not simply promulgate hatred towards the nationality and the mother tongue of the pupils. The schools in question are more like workshops for denationalization. This is why the Albanians are leery of sending their children to attend them.

3. Teaching staff

As to the teaching staff, it must be mentioned that teachers of Albanian nationality are extremely rare. Those who do exist are not employed to teach Albanian or to teach in Albanian. Even hodjas teaching religion to Moslem pupils are obliged to teach in Serbian.

APPENDIX 8

PRIVATE PIOUS FOUNDATIONS"The Yugoslav State pledges to provide full protection to Moslem mosques.

All assistance and authorizations will be accorded to pious foundations (vakufs) and to existing Moslem religious and charitable institutions, and the SHS Government shall accord all necessary assistance for the creation of new religious or charitable institutions such as is guaranteed to other private institutions of this nature." (Treaty on Minorities, Article 10)1. The Yugoslav Government confiscates property of pious and charitable foundations

Not only has the Yugoslav Government not assisted in the creation of new Moslem pious institutions, it has even confiscated the property of many existing charitable institutions (vakufs). Let us refer to a number of cases:

a) The Grand Mosque of Burmalli in the city of Skopje was expropriated without the consent of the community and without compensation. An officers' club was built on the site. It is possible that consent was obtained subsequently by threats from General Terzic who had already made his opinion known: either a million dinar or two bombs to blow up the mosque.

b) The Mosque of Gazi Mustafa Pasha in the city of Skopje maintained a first-rate charitable institution. It held full title to thirteen villages, among them Kreshova, Bullaçana, Rashtak and Novosella / Novoselo. The executor of this property, Shevket Bey, son of Haxhi Mustafa Bey, had all this property confiscated by the Government. This foundation used to distribute 200 loaves of bread to the poor of the city every day.

c) The Fevri Mosque in the town of Tetova / Tetovo was set on fire in broad daylight and surrounded by the police so that people who had arrived on the scene could not put the fire out. It was the fifth time it had been set on fire. The mosque had been saved four times by the swift reaction of the population.

d) In Tetova / Tetovo again, the foundation or vakuf of the Harabati teke (Moslem order), had its property, consisting of about one thousand hectares of farmland, confiscated. Montenegrins were then settled on this land. Deprived of its revenues, the monastery was itself dissolved.

2. The pious foundations of Albanian Christians have been plundered, too

Such torment is not confined to the religious institutions of Moslem Albanians. It also affects the foundations of Christian Albanians. For example:

a) In Gjakova / Djakovica the property of the Catholic church was confiscated and, despite protests from priests and followers, Orthodox Montenegrins were brought in to settle the land.

b) In the village of Novosella / Novoselo, inhabited exclusively by Catholic Albanians, the church was in possession of a çiflik (property) called 'Mali i Vogël'. It was dispossessed of this property which was settled by Montenegrins brought in expressly for this purpose.

3. Not even cemeteries have been exempted

Such unjust measures have also been taken against Christian and Moslem Albanian cemeteries. Here are a few examples:

a) The old Catholic cemetery of Peja / Pec was confiscated and the land was given to a Montenegrin who turned it into a vineyard. The Albanian priest won his case, but the new owner was not expelled, probably for 'political reasons', and continues to grow grapes on the land.

b) The Moslem cemetery in Tetova / Tetovo, which also belonged to a vakuf, suffered the same fate. Part of the land was given to the authorities to serve as a nursery. The rest was distributed free of charge to Orthodox Serbs from the region, and not to the Moslem community (it being Albanian). The tombstones, many of which were of great value due to their artistry, were not handed over to the Moslem community, but were used as construction material for the railway station. Even today, one can seen inscriptions from tombstones on the facade of the said building.

4. Difficulties involving burials

The saddest thing of all in this matter is that the authorities, simply to create a nuisance, have long been postponing the decision as to a new site for a cemetery. In the meantime, the poor people do not know where to bury their dead because the authorities send them from one place to another. Their intentions are obvious: to make the population so desperate, finding justice nowhere, that they will be willing to emigrate. This is but one element.

The same has occurred in many other localities, for example in Peja / Pec, Gjakova / Djakovica and Skopje where the vakufs were deprived of their cemeteries without any compensation.

* * *

In conclusion, we have the honour to stress that these are but a few examples among thousands of others.

[Taken from La Situation de la minorité albanaise en Yougoslavie (Geneva 1930). Translated from the French original by Robert Elsie. First published in R. Elsie, Gathering Clouds: the Roots of Ethnic Cleansing in Kosovo and Macedonia, Dukagjini Balkan Books (Peja 2002), p.47-96.]

TOP