| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1937

Reimer Schulz

Burial and the Cult of the Dead among the Northern Albanian Highlanders

German anthropologist, Dr Reimer Schulz (d. 1941), took part in a German-Italian expedition to the northern Albanian mountains in 1937 on behalf of a “Thuringia Institute for Racial Studies” in Weimar. During a longer stay in Theth (Dukagjin), he measured body shapes and sizes and noted the physiognomic particularities of the natives for an academic discipline that was soon to fall out of fashion. He assembled over two hundred photographs of school children while in Dukagjin, and, as described below, attended a funeral and took the following photos.

Nik Ndou, our dragoman, arrived at our camp earlier than foreseen. It was about 6 A.M. A call had echoed long through the valley early that morning. It began in the north and spread from cliff to cliff. The “Albanian telephone” then fell silent when it reached the end of the valley. This is the name the Austrians gave to the masterful way that the highlanders, the mostly Catholic inhabitants of the Northern Albanian Alps, spread news, by calling and taking advantage of the echo. Nik had heard the news and transmitted it, as a matter of course, to the next house. Now he wanted to inform us of what had happened, so he arrived at our camp earlier than usual. But he did not hustle. Albanians never hustle.

From Nik we learned that Ujk Vuksani, a wealthy farmer from the northern end of the valley, had died the night before and was to be buried that day. Nik wanted to attend the funeral, and we joined him.

A burial in the highlands that includes all the funeral customs lasts a whole day, often late into the night. The tribesmen related to the deceased gather to pay their respects to him and to take part in the wake.

We got to the house of the deceased in the late morning hours. Nik accompanied us first to the home of the dead man’s brother. In the courtyard, large vats of food had been put out for the guests.

The dead man’s brother was waiting for us at the doorway. We greeted him and his son with “Paçi baftin” which means more or less “May the deceased leave you good luck.” They replied, “May the deceased leave you good luck, too,” and accompanied us from the stable on the ground floor to the living room upstairs. Visitors were standing and squatting everywhere - in the stable, on the stairs and in the upstairs room. Five low, round tables had been set up in the living room. At each of them ten men sat on the floor, with their legs crossed. To make room for everyone, they say sideways, with their right flanks towards the table. Cornbread and sheep cheese were brought in for the guests. One man at each table broke the large round loaf of bread and the cheese into bits. A jug of water was also handed around. Corn mush was then served that the guests dipped into liquefied butter. On every table there was a large wooden bowl that everyone ate out of. The guests had all brought their own spoons with them. After this came kos, a type of sour milk. When the meal was over, they all took to smoking. Albanians hardly ever let their cigarettes go out - only when they are eating or sleeping.

After we had eaten, we proceeded to the house of the deceased man. His body was already laid out. From outside we could hear the wailing of the women, and the noise continued when we were inside. The women were sitting around the body, with one of them at his head waving a fan made of fern branches to keep the flies away. The deceased was dressed in his finest clothes. He was wearing a richly embroidered red waist jacket, typical for elderly men. His head was wrapped in a pure-white scarf that covered his new woollen fez. On the jacket were his medals, a Turkish one and an Austrian one, and a skilfully fashioned filigree chain. Around his waste was a loaded cartridge belt, with a pistol in it. His rifle was leaning at his side. He was also wearing white woollen trousers with black strips and a pattern on them, as well as beautifully embroidered socks and pointed Albanian shoes on his feet. A cigarette butt had been placed in his fingers. In his arms there were three apples, a bundle of tobacco leaves, a tobacco box and a bottle of raki. These were symbols of the generosity and hospitality of the deceased. In the afternoon, the body was taken to the graveyard on a narrow bier. Two boards were placed flat under a tree and the deceased was laid out there with all the gifts. The women carefully ordered his clothing, tightened his scarf and fanned the flies from him with the fern branches. Some men then began digging the grave.

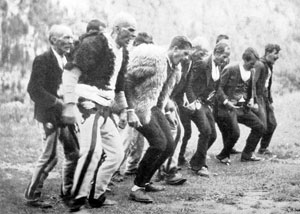

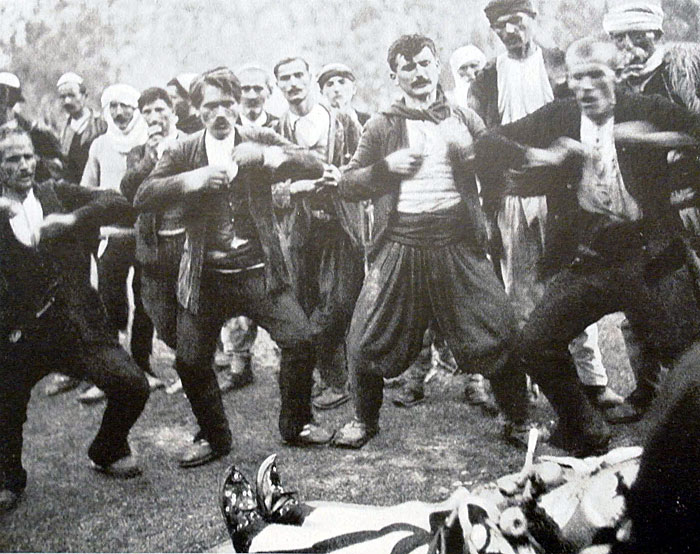

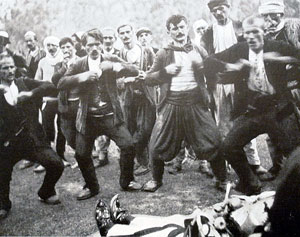

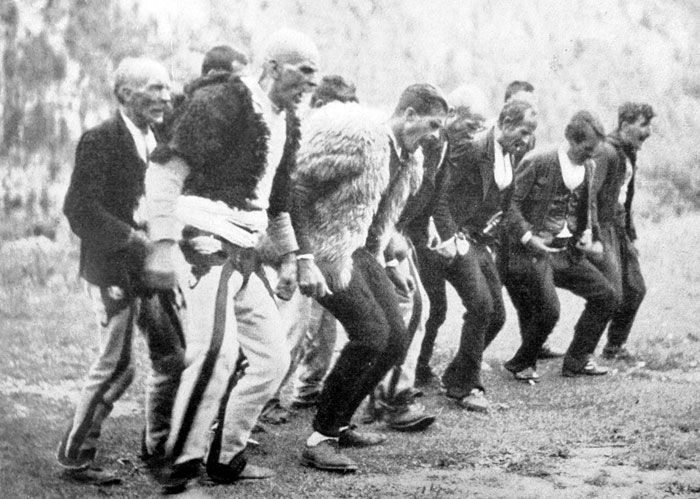

Twelve men, however, remained to one side, about two hundred metres away from the rest. They were standing in two lines, brow to brow. Their leader was in the middle. He bent his knees slightly, took a deep breath and began the tribal lamentation, emitting loud sighs. of “Mjeri, o, o, vëllathi i êm -, mjeri – o, o eh, eh!” (“Woe, my wretched brother!”). The words were repeated over and over, each time louder and with greater vehemence, and was accompanied by gestures. The men beat their breasts and rubbed at their temples. Then they held their noses and moaned, “eh, eh, eh.”

The group took several steps towards the body and repeated the lament and gestures in the same sequence. Step by step they approached the deceased until they stood in a semicircle around him. Once again they began lamenting and fell to their knees, leaning forwards. They held themselves up with one hand on the ground and placed the other at their sides. “Mjeri, o, o, o!” The cries were repeated, louder and louder. The brother of the dead man then came forth and placed his hand on the backs of the moaning men, to tell them that it was enough. The men fell silent and rose to their feet, withdrawing to one side to smoke a cigarette.

The women then approach the corpse and sat closely around it. One young woman covered her face in her scarf and began the wailing of the women. Every phrase she uttered was echoed by the other women with groans of “eh, eh, eh”. The young woman mourned her beloved father who had left them forever. She told of his life, his family, his children, his virtues and his hospitality, but also of his suffering and death. The wailing of the women lasted for about half an hour and ended in groaning and sobbing.

We returned to our camp. We could hear the wild cries and lamentations of the men until midnight, echoing eerie in the night. The corpse was later placed in the grave filled with leaves. Two long boards were placed over it and were covered with earth.

The lamentation of the highlanders, the primarily Dinaric inhabitants of the Northern Albanian Alps, is a moving ceremony evincing tribal solidarity among simple peasants and shepherds. All the relatives bring forth their lament and do so as part of a cult tradition. Solemn and earnest, they reveal devotion and fervour, yet show no sign of ecstasy or demonic frenzy. The lamentation is the way the tribe honours its dead. It is not a fraternity of men or a secret society that is acting here, it is the entire tribe that is openly paying farewell to one of its members.

[Reimer Schulz: Leichenbegräbnis und Totenkult bei den Malisoren. in: Atlantis, Länder, Völker, Reisen, Leipzig, vol. 10 (1938), p. 257-259. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP