| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

Chatin Sarachi in London

1940

Chatin Sarachi:

King Zog of the Albanians:

the Inside StoryPublic figure, diplomat and painter, Chatin Sarachi (1903-1974), known in Albanian as Qatin Saraçi, was born in Shkodra of an influential family. He attended the Theresianum secondary school in Vienna on an Austrian scholarship. It was in Vienna in 1917 that he met and befriended Ahmet Zogu, whom he later helped to power. Sarachi subsequently embarked upon a diplomatic career as King Zog’s consul general in Vienna and, after the Anschluss, as Albanian chargé d’affaires in London. On a trip to the United States in October 1933, where he was sent to negotiate oil concessions on behalf of King Zog, he met and became a close friend of oil baron John Paul Getty (1892-1976), who later visited him in London. Sarachi remained in England after World War II. Chatin Sarachi was also a painter of note, who exhibited his works in London in 1948. He was a personal friend of Austrian painter Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), whom he assisted during the latter’s years in English emigration. Sarachi travelled widely in Europe and was appreciated not only as an artist but also as a master of savoir vivre. In his unpublished memoirs entitled “King Zog of the Albanians: the Inside Story” (ca. 1940), Sarachi attacks his former friend Zog and exposes the king’s corruption.

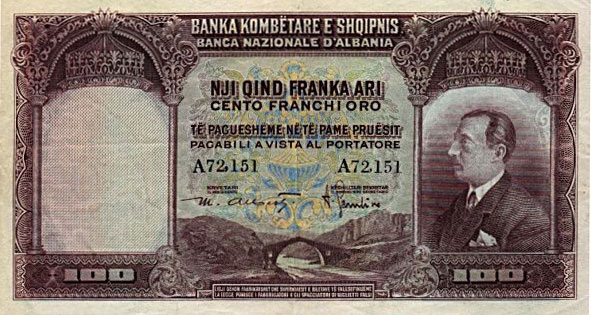

Albanian banknote with Ahmet Zog

(1926)Ahmet Zogu, later with Mussolini’s permission, King of Albania, was born about 1893. At that time, Albania was a Turkish province, and Turkey had no obligatory birth registration anywhere in her Empire. Christians in Albania were obliged to register in the Church, but Zog’s province, having changed en bloc to Mohammedanism in the year 1851, had no kind of registration. Zog’s family belonged to the better, but not the best families of the Mati tribe, as the original clan leader was the Selmani family. At the age of eight, Zog was sent to Constantinople, where he attended elementary school and learned to read and write some ‘Mejtep’ Turkish. Three years of school were all Zog had in his life. He brought a tutor from Albania for himself, called Abdurrahman, a complete illiterate, whose criminal deeds have often been revealed by Albanian and foreign writers. His infamies included deeds again his own people. It is generally accepted that he instigated the murder of his own brother. But after Zog got hold of the indisputable right to rule Albania, Abdurrahman’s base instincts were fully exercised – to which I will refer in detail later in this book. Zog never learned Albanian grammar, and to this very day he is unable to write a line in the Albanian language. He has never written a letter to anybody living in his own handwriting. It is true that he can write in the old Turkish alphabet, but indeed that very poorly, as I was informed by Sulo Bogdo who has see his handwriting and who knows classical Turkish.

It was in 1917 that I first met Zog in Vienna, where I was studying at the expense of the Austrian Foreign Office. There were a few Albanians brought to Austria for education. The Austrians had future designs on this part of Europe, and after the conquest of Bosnia and Herzegovina, being only a few miles from the Albanian frontier, their country was making preparations with all the means at their disposal. The sons of the best and most influential Albanians were brought to Austria. From the south they had the Zakranis, from middle Albania the Toptanis, from Gjacovo [Gjakova] and Kossovo the Curris, and from Scutari [Shkodra] in northern Albania the Sereggis and every male of my family. During the Great War in 1916, after Austria had conquered Montenegro and more than two-thirds of Albania, a delegation of Albanians came to the Austrian capital to pay homage to the Kaiser. Zog was one of the seventy clan chiefs, representing his province Mati.

As we came to speak of Albania, Zog talked to me about its future prospects, and it impressed me deeply to hear such patriotic sentiments expressed by a northern Albanian Mohammedan (as the greatest part of the Mohammedans of northern Albanian were still mourning the departure of the Sultanate).

Three years later, I met Zog again in Tirana, at his uncle’s house. His patriotic enthusiasm was almost fanatic, and from that day I swore to give him all the aid that was in my power.

Albania was ruled in those days by the beys and wealthy landowners. Zog was in opposition, aided by all of the youth of the country. He was an ideal type to rule as no Catholic could reform the country without causing serious religious antagonism. A few years after Zog became prime minister, he carried out drastic reforms by shaking off many cankerous Asiatic habits and customs which had been adopted during the four and a half centuries of Turkish rule in Albania. Zog dared to turn the large Mohammedan cemeteries (generally situated in the heart of every town) into beautiful parks. He gave the enslaved Mohammedan women the initiative to awaken, and later abolished polygamy by decree. He respected all religions, but took away from them the right to interfere in the affairs of State.

At that time, I was preaching and fighting for him in Scutari and throughout northern Albania. In the same way as Prussia was predominant in Germany, so was Scutari in Albania, thus giving this town the right to rule the country. Zog was at that time very little known in this part of Albania. Very few people were inclined to listen and believe me. Even my elder brother, who was then a member of parliament, did not show any kind of enthusiasm to help Zog.

In March 1924, Zog was shot at and badly wounded on the steps of the parliament building. Later he discovered that the young student who shot at him, named Beqir Valter, was incited by a clique of young Albanians who saw in him a coming danger…

Later that year, in Yugoslav exile, Zog seized an opportunity and signed an agreement, whereby in the event of his being the victor, he would give Yugoslavia, Sh’Naum and the northern Albanian pastures of Vermoshi. Five hundred White Russian officers, refugees of the Vrangel Army, experts in field and machine guns, and five thousand Yugoslav Albanian civilians formed the army with which Zog marched against the equally strong, but badly equipped Albanians. After a fortnight of fighting, Zog entered Tirana, the capital, as the liberator from the communist plague. However, he was not recognised as such by the nationalists or any other party in the country, who were well aware of his real aim. December 24, 1924, is the date he entered Tirana, a sad day forever in the minds of the people of that perpetually persecuted and suffering country. The first thing he did was to elect himself President of Albania. At that time, he already showed signs of megalomania.

It is no exaggeration to state that Ahmet Zog is 75% illiterate. He has never read more than two or three books in his life, and those were undoubtedly about Napoleon. He had gigantic plans for the future and, although only the president of the smallest republic in Europe, he liked flattery and expected godlike veneration, even from members of his own family. Those who dared to abstain from overflowing reverence were at once marked as his person enemies. No matter how the foreign press ridiculed him, he craved publicity, and publicity at any cost – in good deeds or crimes. He gradually surrounded himself almost entirely by an illiterate and thoroughly ignorant gang, who never missed an occasion to flatter and praise him as the genius and hero of the nation, although with every day that passed a few more Albanian patriots were found shot somewhere in the country, or in the capitals of Europe. To exterminate rivals and opposition, no means were too bad. In those days, much of the European press used to call Zog the “Ivan the Terrible of the Balkans.”

At his table Zog always expected great attention, and rarely allowed anyone to express their opinion. If someone did so, he used to contradict, and contradict merely for the sake of his contradictory spirit. For a real debate, based on sound arguments, none had the courage, even if they had the knowledge. Jakkoci and I used to look across the table at one another and go on eating with a smile. Whenever we found ourselves alone in the room with Zog, we would express our opinions freely, but when he was cornered, he would change the subject.

There was no one in Zog’s life whom he trusted more than myself. I am certain that he never genuinely liked anyone in his entourage more than me. We understood one another perfectly. I will quote one instance out of hundreds. Archbishop Mjeda of Scutari had come to Tirana to protest against some laws which Zog’s Government had put into force and which the Archbishop thought incompatible with the principles of the Church. Every time Zog had an audience, I went out into the hall with the rest of the secretaries and adjutants. The bell rang and Zog asked for my presence. As I entered the room, Zog looked straight into my eyes and shouted at me with some vigour: “Why did you forget to give the order to the Minister of Justice about the Church laws, of which I told you the other day?” I grasped the situation at once from his face and answered exactly what he wanted, without any hesitation, saying: “I am sorry and beg Your Excellency’s pardon for my forgetfulness.” Zog turned towards the Archbishop, saying: “You see, Mr Sarachi is a Catholic, too.” Now the laws have gone through, but I will undo as soon as possible what has been mistakenly done.” I had not heard anything about these laws, nor had Zog talked to me about them. However, the Archbishop went back to Scutari satisfied and, once we were alone, Zog had a very good laugh. I could mention several other such incidents. Naturally Zog’s promises never materialised, and in later days they became the joke of the country.

I have lived mostly abroad since my tenth year, but in between, I was often in Albania, visiting my mother and brothers, who were all married and working there. I was particularly attracted in the winter months by the shooting in Albania which is still one of the best and wildest countries in Europe for this sport. One day, early in 1929, I came back to Tirana from a long shooting expedition in the wild marshes between Durazzo [Durrës] and Scutari. I went straight to Zog’s so-called palace, which in reality consisted of four rooms, and was a type of house which, in countries like England, would not even be honoured with the title cottage. I went at once to His Excellency’s bedroom. I was so perplexed that I could not believe my eyes, for I saw something so amazingly curious that I stopped almost petrified at the door and gazed for a long time before I could give the usual greetings. Zog turned towards me with a smile of satisfaction, saying: “I see you like my new uniform, and so do I. The man who cut it was an artist.” Everyone in my country knew that I was the only person in Albania, excepting Zog’s mother, who could tell him things that nobody else would have dared mention anywhere; not even his own sisters had that privilege. I saw in Zog the future of Albania and in those days I almost worshipped him. Seeing him in front of the mirror, I did not want to hurt his feelings over such a small, personal and somewhat childish matter. He was still standing in front of the mirror in a full uniform of white, a long white aigrette on the white fur cossack hat, with white embroidery, white tunic, white breeches, white gloves and, to my amazement, white patent leather boots. Even the ribbons holding the sword were white. “Tell me,” asked Zog again, “do you like it or not?” As he did not get an answer, he went on, “Well,” he said, “I am sure my soldiers will like it, and that is all that matters.” I saw he understood my insulting silence. It was not my intention to hurt him, but the situation made it appear that way. The next morning, he arranged a review of this personal guard and, on this very unimportant occasion, he showed to his two hundred and fifty clan soldiers, the magnitude and splendour of his carefully designed and tailored uniform.

King Zog and his sisters

in white uniforms (1936)Francy, his great favourite, had arrived from Vienna and was living just behind the walls of the park grounds, where the parade was going to take place the next morning, and Zog’s main desire was to impress her. Unfortunately a kind of court photographer managed to take a single photograph depicting Zog in his snowy-white peacock uniform. This photograph has, since that date, always been reproduced by the world press wherever Zog comes into question. The Viennese magazines and newspapers were the first to reproduce the photo, and unpleasant jokes and remarks were made about that splendid uniform. René Vanlande, in his book En Albanie sous l’oeil de Mussolini, wrote in 1933:

“Et le président préside en grand uniforme blanc à brandebourgs noirs, avec sabre courbe et bonnet d’astrakan à aigrette vertigineuse. La dignité royale n’a pas changé grand-chose à sa tenue. Peut-être l’a-t-elle plutôt simplifiée? Un monarque peut dédaigner certaines fioritures indispensables, en Albanie tout au moins, au prestige d’un simple président de république. Et puis, il parait que, sur une scène parisienne, on a (blagué) l’aigrette de Sa Majesté, laquelle en aurait éprouvé quelque chagrin.”

Francy had a true Viennese sense of humour and, one evening after dinner, she took me into a corner of the room, leaving Zog alone at the table and, giggling, she produced from her bag and showed me the photograph from a cutting of one of the Viennese magazines. The next day, the Minister of the Interior got orders to collect and destroy all the reproductions of that photograph. That of course only made the matter worse. Gradually the uniform, as Monsieur René Vanlande writes, although still in its ridiculous shape, was somewhat amended, black boots and some black cordons having made the change.

A few years previously, I had been obliged to help my friends Zog and Jakkoci financially. I had no money of my own, but in the name of my family I had some credit, so that I used to borrow money and lend it to my friends. It is true I was always paid back on the date. I never had any financial help or assistance from Zog. For the first time, after we left Belgrade for Vienna, Zog handed me about £200 in thousand dinari notes out of the £250,000 he got in cash from Pasic in Belgrade, with which he was supposed to pay for all his officers and men and the five thousand mercenaries who came to help Zog from the Yugoslav frontier to Tirana. At the time, in order to confuse the Albanian Government, we left from Belgrade for Vienna, before the great attack. After that short stay in Vienna and Prague, Zog turned suddenly and went straight to the Yugoslav Albanian frontier, from where he started his successful campaign.

Between the Viennese and Prague nightclubs, expensive fur coats and extravagant jewellery, a great portion of the Pasic money had already gone, and now in Tirana, Francy was helping speedily to finish the rest of the money. Jewellers and dressmakers from Paris and Vienna were running in and out of Francy’s residence almost as frequently as the cabinet ministers at Zog’s house.

I had just gone to Bari in Italy where I had to take over the consulate and watch the movements of the great bulk of our opposition leaders, including Fan Noli, who had fled there. I had hardly been there ten days when something happened, which, though not extraordinary in Balkan politics, was surprising to me. A young Albanian shot dead one of our opposition leaders. The assassin had come to my office the previous day and had smilingly told me that he had come to Bari to fulfil some great patriotic deed. I had known him well since my schooldays. He was a native of my town and I knew that he was an adventurer and great coward. I did not therefore even bother to warn the opposition leaders, with whom I still retained a good private relationship. One year before that happened, I had been able to save the life of that very victim in Bari, and he and his family expressed thanks to me and my relatives. I saved him from an ambush of “Zog’s party,” having had a warning about a week before the attempt took place. At that time, I did not think that Zog was directly involved in such deeds. After this tragic episode I had the opportunity of being Zog’s most trusted man and was able to save many human lives. It was natural that my name should be connected with Zog’s in this criminal deed. I went to Tirana to find Zog and his brother-in-law, Ceno Kryeziu, in very high spirits, cheerful and proud of the Bari deed. That was the turning point of my feelings towards Zog.

Money was scarce in Albania. The revenues and taxation could not bring enough money in to satisfy Zog’s extravagant expenditures. With Francy and her staff in Tirana, there would have been no bank large enough in the Balkans to satisfy her. At that time, Zog had fixed his State income at about £35,000 a year, although indirectly he was taking from the poor Albanian treasury perhaps twice that amount. The Government of Albania was forcing the Minister of the Treasury to go on paying out for the 5,000 mercenaries, who had already left months ago. The expenses for the keep of these 5,000 therefore only existed on paper, and the money went directly to Zog’s private purse. The Treasury’s officials knew of this manipulation, and they were well aware that the list of the 5,000 mercenaries which Zog was presenting regularly every month was a bad fake. None dared to make the slightest remark. People were arrested and put in gaol for much smaller offences. Many people who had opposed Zog’s meteoric rise were arrested and shot without a trial for “trying to escape.” The Gestapo in Germany or Stalin’s GPU get orders from some higher officials to torture and kill people, but in those days in Albania, some underling who wanted to curry favour would shoot someone who had once dared to raise his voice against Zog, and in some cases this excuse was used to give vent to personal hatreds.

I was staying in Tirana in those days. Two officers of high rank, personal friends of mine, but who had fought with the Government’s army against Zog’s invasion, were put in gaol, and were on the list of those to be shot for “trying to escape.” One day at the Palace, Zog had, in my presence, a long talk with Musa Juka, one of the most sanguinary creatures in the world. When Musa Juka left, I begged Zog to spare the lives of the two young men, who after all were friends of mine, and who had not done anything to deserve such radical punishment. Zog, looking in amazement at me, said, “You want to spare those two, those whose soldiers have killed Ferid Frashëri?” I argued until he had no other course but to change the subject. He went on talking on his own, but I insisted on my point. It was the first time that he had not at once granted me my plea. I left him almost without a word. At seven o’clock in the evening, an officer of his guard came to my house and invited me, in Zog’s name, to dinner at eight o’clock. I saw that I had won my case. No doubt Zog had felt conscious-stricken for refusing my request.

It was eight o’clock, but Francy had not arrived yet. When I entered Zog’s room, he said, with a smile, “I have given you your two friends. One day,” he said to me, “mark my words, you will regret it.” He gave me the order to telephone at once to Musa Juka to suspend the plan. I telephoned at once and told Juka that if one hair of the heads of those two men were touched, His Excellency would hold him, Musa Juka, personally responsible. Two days later, a very old woman, dressed in black, came to my brother’s house, where I was staying and with tears in her eyes, she expressed her gratitude and that of her son, who knew that he was now safe.

At about nine o’clock, Francy arrived, painted and perfumed, and ready to compete with any Messalina, and I am sure that Cleopatra or Mme Pompadour would not only have admired her jewels, but would have envied her perfect slender figure. She was always immaculately dressed, and of course with the creations of the best dressmakers in Europe. Her face was pretty, but not interesting. It reflected her ignorance and betrayed her origin. She was the daughter of a nurse and gardener near Vienna, and had as education three obligatory years of schooling. She was a province cabaret dancer when she met Zog in Belgrade, a few months before Zog conquered Albania. Zog was extraordinarily generous with Francy. That was an era when Zog used to live from day to day. He was indeed extremely generous not only with Francy, but also with everyone else. Francy was one of the few persons who knew how to treat him, and no doubt at that time Zog was madly in love with her. It could hardly be otherwise, for Zog saw no other women for weeks and months, except those of this own family. He never left his house as prime minister and dared much less to do so now, having accumulated a few hundred vendettas more on his personal account. Francy was everything to him. At that time, Zog knew very little of the German language, but he was taking lessons, and Francy was helping him in practice. She knew not a single word of any language but her own. So Zog learned Francy’s German, which of course was far from being the “King’s” German. In time he picked up all the common expressions, which were Francy’s style, and in addition he lacked the grammar, but he rattled the language off, impressing the ignorant with his ‘fluent’ German, but putting anyone who knew better in a difficult position, as it was not easy to abstain from laughter. Francy used to call him names in my presence which embarrassed me. Her favourite expression to him, especially after a few glasses of champagne was “Du Gebirgstrottel” (you mountain idiot). Of course Zog could do nothing else but put a good face on her evil language. When Francy used expressions of this kind, Zog used to tell me in Albanian how lovely all that sounded in her voice, and how much he was amused at Francy’s expressions. Francy herself, on my frequent visits to her, used to tell me how Zog begged her not to make fun of him in my presence. At that time, Francy had a considerable bank account, and many £10,000 worth of jewellery, so she felt more than independent, and she was tiring of the secluded and intolerable life, as she used to call it. She would not have minded any kind of break. Francy was not allowed to go out of the house, except at night, accompanied by one of Zog’s aides-de-camp, through the guard’s grounds to Zog’s palace. During the daytime, as she felt terribly lonely, I used to go and visit her. We used to talk about the gaiety and beauty of Vienna. After conversations like these, Francy used to fall into melancholic depression…

One day, I was summoned to the palace suddenly, and once in Zog’s office, he started: “Chatin, we need money, and we need it urgently. I have been going over the reports of my cabinet and I believe that Zinoviev has spent over two hundred thousand pounds on Fan Noli and company. Who on earth is more naturally communist than the poor Albanians? We have no principles which would be an obstacle to adopting Marx’s ideologies. We are an agricultural country, without capitalists, and do not even possess a single factory. I intend to negotiate with the Soviets and comply with their wishes, which they could not fulfil through Fan Noli, but on one condition, that the Soviets give me the amount of three hundred thousand pounds. The nearest and best Soviet representative is, as we known, in Vienna. The Soviet minister’s name is Joffre. Go as soon as possible and talk to him.”

Although Zog took me by surprise, I had time during his talk to think out my first reaction. I answered promptly without the slightest hesitation, approving entirely of his splendid idea. Two days later I left for Vienna. I had been there only about ten days when I received an impatient wire from Zog, asking for news. I was enjoying myself there and had no intention either of taking the steps he required or of putting an end to my delightful journey. I wired back saying: “The response from the Central (meaning Moscow) is expected in a few days.” I had not been near the Soviet legation, nor had I tried to see any of them. I had my own plans and wanted to fulfil them by first getting rid of all obstacles. I will refer to these later in detail.

I returned to Tirana via Rome about a month after I had left Albania, and went straight to Zog to report the Soviet ‘response.’ I told him that the Soviets would on no account enter into any kind of negotiations with a man who had killed all those showing sympathy with the Soviets, “but,” I added, seeing Zog’s face turning to scorn, “I have a way of getting all the money we need. I have had several conversations with my friends in Rome, and they are prepared to give you all the material assistance needed.” I went on to explain how we could build up the country with the help of a nation which not only had the means, but also had the interests of our country at heart, a nation that would never be a direct menace to Albania. In those days, these convictions were shared by everybody who knew the political situation in Europe, but none could foresee the meteoric rise of another man who was to give Europe an entirely new face, and plunge the world again into war and destruction.

Zog wanted money quickly, and a lot of it. I was allowed to stay only two days in Tirana, and was quickly sent to Rome on a specific mission – money! I went to see my young Fascist friend, a member of parliament, Alessandro Lessona, who later became the Undersecretary of State for the Colonies, and during the Abyssinian War was Minister of the Colonies. He was a personal and intimate friend of Mussolini. To justify his need for money, Zog invented a story which I was to tell Rome. Zog’s story was that a certain unrest was noticeable in the tribal leaders of the country, caused by lack of payment to them and their mercenaries, and the sum that Zog needed was about two hundred thousand pounds in cash. It was true that some of the leaders expected remuneration for their previous services, but although Zog got the money from Italy later, they never saw a penny of it. Of course the Italians demanded some concessions, but at that time, they were only of an economic nature. Their first demand was some extension of their southern petrol concessions, and the creation of an Albanian National Bank. The money was brought in foreign currency in two large trunks, accompanied by Alessandro Lessona himself, who travelled from Brindisi to Durazzo on an Italian destroyer. Durazzo was the spot where Zog first came into contact with the Italian Fascist regime. I was well aware of Zog’s urgent need of money for every day big bills were promptly paid to dressmakers and jewellers of Paris and Vienna.

Francy, who had arrived in Tirana with two small suitcases, left Albania a few weeks later with two military lorries full of luxurious brand new trunks. I became very worried about Zog’s extravagant expenses and foresaw further money needs, which would lead him and our country to what it did. I thought it was my duty to warn him, and one day I did, and gave Zog my views. I even mentioned historical facts to persuade him that even men wealthier and more powerful than Zog himself had been ruined by the type of woman that Francy was. When I had finished my long talk, he smiled at me and patted my right shoulder with his left hand, assuring me that Francy was the most modest girl in the world, and that I wronged her by claiming that she was a ‘gold-digger.’ “Don’t you realize she is in love with me?” Zog asked. “She is a good soul, and nothing like the Viennese!” Though I knew from Francy herself how strong her love for Zog was, I left it at that.

Although I was only twenty-four years old, Zog offered me for my services any foreign diplomatic post I wanted, including the London legation. But I was brought up in Vienna, where I had so many good friends and happy memories of my student days, and at that time I did not know as single word of English, and knew almost nothing about the ‘foggy land’ of the English, except what I had learned at school. I chose Vienna, where I was installed as the Albanian Consul General, which post I considered a sinecure. I used to spend more than half the year shooting and travelling in various parts of central Europe, and I liked Budapest, Berlin, Paris, Cannes and the Lido of Venice. Although busy travelling, I never missed an occasion to read thoroughly the two Albanian daily newspapers, and with my brothers I had a well-organized correspondence, which informed me in detail about the internal situation in Albania.

I visited Zog, on an average, every third month, and I never let a week pass without sending him direct reports describing the international situation as I saw it, and warning him to make good, things that were being done badly in Albania, both with and without his knowledge. By this method, I was often able to rectify, and sometimes prevent harmful and bad deeds. His adjutants, who were my best friends, told me how they had orders to put my letters always in front of all others, and none but Zog himself was allowed to open them. I used to write all my letters to him with my name on the outside. I knew for a fact that he read them diligently, as often he would make a note of minor points, and bring them up in conversations sometime later, and we would discuss them. I had several times mentioned in his presence the wise Arab saying:

“Mankind is divided into three categories: man, half man and animal. Men are those who are clever and take advice; half men are those who are clever but do not take advice, and animals are those who lack cleverness and do not take advice.”

Zug was clever and at that time he did take advice, but alas, with the growing of his power, wealth and honours, only a few years afterwards, he thought himself a really great man, and was thoroughly persuaded that his task could be accomplished only through him and him alone. His megalomania had already reached a degree of ridicule.

None around Zog dared to tell him that what was being done was bad and wrong. Although this flattering approval was perhaps not expressed with a clear conscience, they continued to do so for their own sake. Most of them were illiterate parasites and opportunists, and feared the loss of the jobs they would never have dreamed of possessing under normal conditions. Their ambitions for money and power caused them to forget every degree of human sense. Most of them even went so far as to sacrifice their own self-respect. Like their master, they considered everything and everyone merely as a bridge to reach their aims. Zog’s tutor, Abdurrahman and Musa Juka, the henchmen, would walk over corpses on their way to wealth.

The days I spent in Albania, from seven o’clock in the morning until midnight, were spent almost entirely at Zog’s palace, for so was the wish and order of my friend. I had, on these frequent occasions, enough time to study the different types and characters of those surrounding him. Before this book is finished, I will have cause to mention a few of them. Between the audiences that Zog had, I used to enter his room and continue our interrupted conversations. One day, as there was a cabinet meeting, the ministers were walking through the palace gardens. I knew them all very well, and so did the whole nation. Zog and I were standing near the window, and I said to him: “I do not wonder how you got hold of so many illiterates, for our country is full of them, but I am astonished at your capacity for collecting around you so many traitors and anti-Albanians in one bunch.”

“They are my circus,” Zog answered. “What they know and what their feelings are does not interest me. As long as they submit to my whip, I am satisfied, and I keep them.” I countered: “Everyone in our country knows their past and their capacity. I am not surprised at your admission, but I am surprised to know that you are using this kind of people to govern and to move our country towards prosperity and progress. You could have found ‘yes men’ with a better past, and not ones so obviously against everything connected to the patriotic advancement of our country. They are not only disliked and hated, but you are being blamed by the public, and not them.”

“Power is justice, and I have power. The strongman is always alone. Do not fear the ignorant and characterless people. Fear the clever, those with knowledge and straight character. That is why I think my ministers are harmless. They will always do whatever I want without a murmur,” Zog replied.

“You may be able to oppress and rule the country for a long time in the way you have chosen, but you will achieve no progress surrounded by such pathetic creatures, whose reputation is more than bad. The future historians of Albania will mention your name with contempt. Your minister, Musa Juka, has not only given documentary proof that he is a traitor, but has stamped the documents himself as an unscrupulous criminal and thief. Consider that, with all the persecution and oppression, there is still open criticism in Albania, and one day an armed conflict might easily break out. I hear much of this outside your very house.” Zog replied: “As long as they only talk about it, it is not dangerous, and should it come to armed rebellion once more, I will win again. I have tried it, and have experience. They hate me intensely and you, my dear friend, not less. We have killed their idols – so they say – and they will never forgive us for that. If I could gather around me the intelligentsia of the country, and if I could come to an agreement with them, I would dismiss my mercenaries at once and would do the same with the standing army, but, alas, that is impossible for the moment, believe me!”

It was true they hated him, and I was his Hephaestion, so they hated me with equal vigour. But still there was some hope of reconciliation. If Zog had made an attempt to get the young people to collaborate by giving them small concessions, they would have given him and the nation all their help. But no honest and conscientious person would have put his signature to all the official and unofficial acts that Zog was asking them to sign.

I left Zog’s house very perturbed and more desperate than ever. I had very good friends and my brothers, who were always ready to help me with every means at their disposal, and the advice I received from them was often very helpful. They knew I was desperate and realised the position I had got myself into, but they begged me to hang on and try to help the country as much as I could. They knew for a fact that I had not only managed to spare their lives, but that I had also been able to hinder many other evil deeds. Every time I went to Albania, my eyes saw more than they desired to see, and my ears more than they should have heard. I could, and I would have left Zog and the country forever, but at that time it would have done the country very little good, and it would have placed my family in a desperate position, knowing my friend’s ruthlessness. I never stayed long in Albania, except in the winter for several weeks for the woodcock shooting, which is still the best in Europe.

I was outside the country when news reached me that an Albanian National Bank was going to be created. I knew the wish of the Italians and I warned Zog in time not to conclude any definitive pact on that subject without first having consultations with a foreign financial expert. In matters of finance, Zog was entirely ignorant and did not possess even the most elementary knowledge. The bankrupt Myfid Libohova, half Tcherkessian and half Albanian, was at that time at interim finance director at the foreign office. It was generally known that his estate was mortgaged for eight thousand Louis d’Or. After the National Bank statute was passed through the so-called parliament, not only did Myfid Libohova pay his debts, but he had enough money left over to buy a big palace in Rome, and even lent money at interest. Of course, in a small country like Albania, it was impossible to hid facts of even lesser importance, and the change in his position was much too obvious and important. It was thoroughly discussed and commented on. The Mohammedans in my country say: “A minaret cannot be hidden in a sack.” Zog’s case of course was much more obvious, as I will explain in detail.

I rushed back to Tirana and I knew the first thing to do was to ask Zog for my share, as I understood in Rome that he had received five million gold francs for that special occasion. When I told Zog what I had heard in Rome, he laughed at me, and said: “But my dear friend, the whole capital with which the Bank was formed is only twelve and a half million gold francs.” After a further and long explanation, he admitted having received only two million gold francs, and he said that he was prepared to give me my share of that. I had no power to claim my share more definitely, and had to be contented in the end with half of his original promise, amounting to five thousand Louis d’Or.

I went straight to my brothers and told them everything in detail, and begged them, in case something happened to me, not to forget this particular point of Zog’s deed, in the book which one of my brothers was keeping, where he noted down every happening in Zog’s regime. In taking bribes, Zog had lost the last spark of human decency. Not only was he accepting them, but he was stipulating the amounts. Italy was feeling Zog right and left. In reality, it was not Italy, but Mussolini’s personal famous generosity which, as I often heard from my friends in Rome, used to trouble the minds of his financial advisers. Zog was paid every month in Lire, to pay the mercenaries who, actually, only existed on paper.

At that time, Fascist Italy had scored no special foreign political successes, and the Fascist Party was anxious to present the Italians with Albania. The wealthier Zog grew, the greedier he became, The more influence he got, the greater was his thirst for power and decorations. With the growing of his power, his jealousy and distrust reached terrifying proportions. His brother-in-law, a complete illiterate, was a born Albanian but a Yugoslav citizen. He was a native of Cossovo [Kosova], an almost entirely Albanian populated province. He had been in Belgrade the trait d’union between Zog and Pasic. He was now the governor of the town of Scutari, commander in chief of the forces, and so on. Belgrade trusted this man more than anybody else, for Ceno Kryeziu was more Serbian than any Serb could be. In Belgrade, not only was he persona grata, but a personality. On several occasions, at the time of our refuge there, I went round with him to ministers and commanders, who treated him not only with great hospitality but also with respect. He was twenty-nine years old at the time he was minister of the interior in Tirana, and in this capacity he did great service to Belgrade. The first thing he did was to hunt down the few Yugoslav komitadjis who had taken refuge on Albanian territory. He captured two men, on whose heads Belgrade had put large sums of money, and without trial, he executed them both. A photograph was taken, showing Ceno in the middle of the hanging scene. That of course was to prove to Belgrade how well he was doing his job. Some Viennese magazine got hold of that particular photograph and placed it on the front page. The central European newspapers in particular were printing news about the “Ivan the Terrible of the Balkans” almost daily.

Ahmet Zogu and Ceno Bey KryeziuAgain in Tirana, the first thing I did was to report to Zog about this unparalleled crime in Albanian history. “No one on earth with Albanian blood in his veins would have dared to commit Ceno’s detestable crime.” These were almost the first words I said to Zog, when I handed him the magazine. His consternation at his first glimpse of the publication was enormous, and he at once gave orders to summon his brother-in-law. Of course, Zog knew of Ceno’s deed, and that kind of job was probably part of the agreement that Zog had signed in Belgrade, before getting money and soldiers from Pasic. We were forced to do so,” Zog said to me, “but not with printed documents.” He was in a rage. Ceno arrived a few minutes later, and as soon as he entered the room, an angry voice was heard shouting, that of Zog. The whole conversation lasted not more than a minute or so, and Ceno came out, with tears in his eyes, and rushed out of the house like a madman. It was the first row they had had. Later Ceno realized who had given Zog the magazine and from that moment on he hated me more than anyone in or outside Albania. Zog’s family life was entirely upset by this event, and every effort was made for a speedy reconciliation which was effected about forty-eight hours later. I was present when Ceno saw Zog the next time and the subject was not brought up again. They genuinely liked each other.

After lunch we were talking of the lives of great men. Ceno, of course, as an illiterate, knew only about those who were living, but Zog could go on and on forever about Napoleon’s life. He knew it thoroughly, every date and event, and even the names of all his generals. In this one thing he had a very good memory. Suddenly Ceno said to Zog: “What is all this nonsense of calling yourself ‘Your Excellency?’ There are so many ‘Excellencies’ here in Tirana. You should follow Napoleon’s example and become king.” “Nonsense, my dear friend, nonsense.”

I never saw Zog’s face change so quickly. He was blushing profusely, like a naughty schoolboy whose conscience was not clear. Were we not hearing every day of democracy and democracy alone? Zog must have remembered this, or perhaps he saw the perplexity in my face, for he promptly countered: “Your suggestion is ridiculous. It will never again be realized in this country, especially not now, in these modern times.” he then asked me some irrelevant question in order to change the subject. That was in 1926.

[excerpt from: Chatin Sarachi, King Zog of the Albanians: the Inside Story, unfinished manuscript, ca. 1940]

TOP