| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

Edith Durham. Photo: Marubi.

1941

Edith Durham:

AlbaniaEdith Durham is remembered primarily for her seminal book publications, in particular her volume ‘High Albania’ (see Durham 1909), but she was also the author of countless articles and ‘letters to the editor,’ in which she endeavoured to present Albania’s cause to the British public and to correct erroneous views. Many of these articles and letters have been published recently in the volume ‘Albania and the Albanians: Selected Articles and Letters, 1903-1944.’ In 1941, following the Italian occupation of Albania, Durham published the following overview of Albania in the ‘Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain,’ typical of her passionate involvement in Albania’s fate. As the most renowned figure of Albanian studies in twentieth-century Britain, she died at her home in London on 15 November 1944, two weeks before the Communist takeover of Albania.

I would plead for justice for one of the oldest and now one of the most unfortunate peoples of Europe. Sympathy is warm for the Poles but the Albanians, who have suffered yet more brutal dismembership at the hands of their more powerful neighbours, are now the battlefield of two rival Powers and threatened with annihilation in a quarrel which is not their own.

The Albanians are descended from the tribes who dwelt in prehistoric times along the Western side of the Balkan peninsula - the Illyrians and the Epirots - before the arrival of either Romans or Slavs. They were not and are not Greeks.

Strabo, writing about the beginning of the Christian era, gives details which show that their tribal system resembled that which has existed until recent times. He states that the frontier of the Greeks was south of the Ambracian Gulf, now the Gulf of Arta. That is further south than today. Albanian territory was taken by the Greeks in 1913. The Illyrians and the Epirots are now known as the Ghegs and Tosks. They speak the same language, have the same customs and form a united nation.

When Rome conquered the Balkan peninsula, Christianity reached the Adriatic coast and Illyria formed part of the Patriarchate of Rome. When the decline and fall of the Roman Empire began, Roman rule was replaced by Slav rule, the peninsula was invaded by the ancestors of the modern Serbs and for a short time in the Middle Ages they ruled a large part of it.

A contemporary account by the Dominican, Father Brocardus, 1331, shows the Abbanois, as he calls them, speaking their own language, clinging to their Church and ‘very harshly oppressed’ by their conquerors. The laws enacted by the Serb Tsar, Stefan Dushan, in 1349 show that they were classed as herdsmen serfs. The Serb Empire was short-lived. At its greatest, it lasted but 25 years, the reign of Stefan Dushan. On his death, the conquered peoples and rival chieftains speedily broke it up and the inrush of the Turks destroyed it completely. Meanwhile the Venetians had crept down the coast. Albanian chieftains rose to power in the mountains; together with the Venetians, they long defended Scutari which finally fell in 1478. But the Albanians were the last of the Balkan peoples to be subdued. Led by their great hero Skenderbeg, famed as the Champion of Christendom, they offered a magnificent resistance from his stronghold at Kruja. On his death of the fever in 1467, they were leaderless and forced to accept Turkish suzerainty. Their position differed from that of the other conquered peoples as they retained a semi-independence under their own chiefs. Race instinct, that blind unreasoning instinct of self-preservation, drove them against their old oppressor and they sided with the Turks in the endeavour to expel the Serbs. The position of the Serbs in the Kosovo district was made untenable. Led by the Bishop of Ipek, they migrated en masse into lands in Hungary allotted them by the Emperor. The Albanians re-occupied the lands from which their ancestors had been evicted and retained them till 1913.

Turning Moslem in considerable numbers, the courage and intelligence of the Albanians enabled them to rise high in the Turkish army and Government. As did the Roman and the Serbian Empires, so did the Turkish Empire reach its zenith and wane. Towards the beginning of the nineteenth century the subject peoples began to think of independence. Ali Pasha, a mighty chief in South Albania, born at Tepeleni in 1744, revolted, defied the Turks and for some fifty years ruled all South Albania from his capital at Janina; entered into diplomatic relations with Great Britain and France and received many distinguished visitors, notably Lord Byron and Sir Henry Holland. In his old age, he was overpowered by large Turkish forces and his head was carried to Constantinople as a trophy in 1822. I found his name still honoured when I was at Tepeleni in 1904.

Meanwhile Russia fixed greedy eyes on Constantinople and incited and aided Greeks, Serbs and Bulgars to revolt. The Greeks, aided also by Great Britain, were the first to recover independence and be given a foreign king. In 1876-77, came the Russo-Turkish War to liberate the Slavs. Again the Albanians sided with the Turks and put up a very strong resistance to Serb invasion, defending their towns of Djakova, Prizren and Prishtina successfully. Turkish resistance broke at Plevna. There followed the Treaty of Berlin and the Eastern Roumelian Commission. Much wholly Albanian land was allotted to the Serbs, Montenegrins and Greeks. The Albanians formed the League of Prizren, summoned their forces and saved much of it. The northern tribesmen kept the Montenegrins out of Gusinje. I knew fine old Marash Hutzi of Hoti who organized the defence. Dulcigno, a purely Albanian town and Antivari, inhabited solely by Moslem and Catholic Albanians, were handed over to Montenegro. The Janina district, however, was saved from the Greeks and Kosovo from the Serbs.

At this time Lord Goschen and Lord Fitzmaurice on the Eastern Roumelian Commission, strongly favoured forming a large and independent Albania to include all Janina vilayet, all Kosovo vilayet and a considerable part of Macedonia. Lord Fitzmaurice took very great interest in Albania and corresponded with me about it for some fifteen years. He maintained that had an Albanian State been then formed, both the Balkans and Europe would have been spared much bloodshed; each of the respective peoples would have had a fair share and balanced each other. But the prejudice against Moslems was then too strong. I became interested in the Albanian question in 1903. A revolt of the Bulgars of Macedonia who wished to join free Bulgaria was sharply suppressed by the Turks, leaving a mass of burnt villages and starving people. As I had done much Balkan travel I was asked by the British Macedonian Relief Committee to act as their agent in the Ohrida Presba district. The Turkish Government gave permission and facilities. Our headquarters were at Monastir (now called Bitolj and included in Yugoslavia, but at that time there were no Serbs there). Our assistants, kavasses and Interpreters were mostly Albanians obtained from the British and Foreign Bible Society which had a depot at Monastir. From them I learned of the strong nationalist spirit then at work. Without our capable and honest Albanian staff, the work would have been far more difficult. The Governor of Ohrida, too, Mehdi Bey Frasheri, was an Albanian, a just and kindly man who was a great help to me. I regret to say he is now interned in Italy for having opposed the Italian invasion: may he live to see his land restored to independence. When the relief work was ended in the spring of 1904, my Albanian friends begged me not to return to England but to travel through Albania and see conditions for myself.

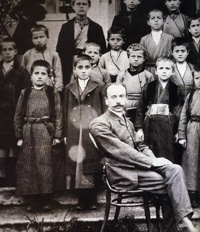

Early Albanian school in Korça.At this time the Turkish Government, afraid of the rising national spirit of the Albanians, tried to suppress it by forbidding the printing and teaching of the Albanian language under heavy penalties. Faik Bey of Konitza published an Albanian paper in London which was smuggled into the country. George Kyrias, an employee of the Bible Society, prepared some books of the Bible in Albanian and the Society published them. The Society had leave to sell its publications in the Turkish Empire but the Turks had not reckoned on Albanian books. An Albanian colporteur was to try to sell these through the length of Albania. Would I go with him? I joined him at his home at Leskovik. It was an inspiring journey. I first visited Koritza, Korça as the Albanians call it. It was the active centre of the independence movement in South Albania, whose first object was to rid the land of all foreign influence.

A sister of George Kyrias, a brave and very capable woman, went to America aided by the American missionaries, was trained there and on her return was made mistress of a Girls’ School under the protection of the American Mission. She used American textbooks, gave her lessons in Albanian and destroyed all writing after the lesson.

The Turks searched vainly for the forbidden language. Christian and Moslem girls flocked to the school, learned to read and write and taught their brothers. All worked hard to counteract the influence of the Greek school and priests which the Turks permitted by way of suppressing Albanian. We went on, wherever we found an Albanian Governor, we were welcome to sell as many books as we could. At Berate, where there was a Turkish one. All our Albanian books were confiscated but as we had a secret store awaiting us ahead, this did not matter.

At Berate, I first heard of the efforts being made by the priest, Fan Noli, to form an autocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church and free the land of Greek priests. At Berate, the Christians complained that the Greek priest informed against persons possessing Albanian books. Fan Noli’s long years of work were crowned with success after Albania became independent. The autocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church was legally established and there are now no Greek priests in Albania unless some have accompanied the invading Greek army. The clergy are all Albanian and the services are held in Albanian. The Head of the Church is Archbishop Kissi whose seat is at Tirana. The Church is thus on a par with those of the Serbs, Greeks and Bulgars, which are all autocephalous. Bishop Fan Noli is head of the Albanian colony in America.

I would emphasise the formation of the Albanian Orthodox Church as some newspapers describe the South Albanians as ‘Greek Church’ and its adherents as ‘Greeks’. This is as incorrect as it would be to reckon all Roman Catholics as ‘Italians’. Not only Christians but Moslems hastened to buy our books. At Elbasan, in about an hour we sold 70 to Moslems. “Now,” aid a young gendarme joyfully, “I can teach my young brother to read.” At Elbasan, I found a movement to form an Uniate Church in order to stop Greek influence.

Thus we peddled books through all the towns of Albania and reached Scutari, travel-worn but satisfied. There were then no made roads, the journey was on horseback, fording rivers where horses nearly swam, plunging through marshy land where they were bogged to the shoulder and had to be dug out, and having to walk when the track was too bad to be safely ridden. Scutari was the centre of the independence movement in the North. Here there were more opportunities for education. Austria and Italy both coveted Albania and each tried to outdo the other in trying to win over the Albanians. So there were schools both for girls and boys, a boarding school for the mountain boys, a technical school and a printing press all under Austrian or Italian protection. The Albanians profited and studied eagerly.

Then came the Young Turk revolution in the summer of 1908. It promised freedom and equality for all. The Albanians played a major part in its first successes. The Kosovo men marched on Uskub (now called Skopje but then a largely Albanian town). They evicted the old governors from the district and occupied the town. Our Vice-Consul, a friend of the Albanians, testified to the good behaviour of the Albanian troops.

The Constitution was proclaimed, Scutari was wild with joy. Thousands of mountain men, in finest array, marched into the town, were feted and feasted. We fired revolvers (I had one in each hand) into the air till not a cartridge was left. Not an accident nor any disorder occurred. Said the French Vice-Consul: “What a people this would be with a good government!” They went back to their mountains happy and hopeful.

There was to be freedom of the press. Albanian newspapers sprang up like mushrooms in the night. Schools were opened with great rapidity. A Congress for the standardization of the alphabet and orthography was held at Monastir and a universal one adopted. The foreign schools had used separate systems. Long live Albania! She was to have her chance at last. Never again shall I see such a joyous resurrection of a people.

I went over the mountains to Djakova which had long been closed to foreigners and over the Kosovo plain to Prizren, Prishtina and Mitrovitza, back through Mirdita to Scutari. Everywhere the Albanians meant to have freedom. Alas! The Young Turks made every possible blunder. Rightly handled, the Albanians would have supported them as before against foes. But before the year was out, the Albanians realised that no freedom was to be expected. I talked in vain to the two Young Turk Governors. Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria and Montenegro were all determined not to let the Young Turks succeed, for this would mean no more chance of land grabbing. They formed the Balkan League to overthrow the Young Turk Government before it should have time to consolidate.

In 1910, the Albanians of Kosovo revolted, being encouraged to do so by the Serbs who promised them help. They were led by the gallant Iss Boletin. Glad news came to Scutari. Iss had made terms with the Serbs. A Serb officer and his men were aiding him, even sharing quarters with him. Serbia had recognised Albania’s right to independence. The age-long feud between Serb and Albanian was to cease. Iss believed and trusted the Serb and was cruelly deceived. The Serb in question was Colonel Dimitrijevitch, a leader of the gang which so brutally murdered King Alexander and Queen Draga in 1903, and head of the notorious Black Hand Society which planned a few years later the murder of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and launched the World War in 1914. One of the greatest criminals of his time. Disguised as Albanians, Dimitrijevitch and his men committed many murders, among them that of Popovitch, the Governor of Berani, who though a Montenegrin by birth was a supporter of the Young Turks and wished to make Berani a little model province. He was hacked to pieces and the crime was ascribed to the Albanians. But his widow, a Frenchwoman, declared to me that the Serbs had killed him. This revolt of the Albanians succeeded in completely alienating them from the Turks, as the Serbs intended it should do.

In 1911, the King of Montenegro offered to help the tribesmen of the Northern mountains to obtain freedom. They too believed him and rose. I was at Constantinople and returned in haste. The revolt was in full swing. King Nikola asked me to aid the crowd of women and children who had fled into Montenegro in wretched plight. Montenegro was supplying the rebels with arms, ammunition and advice. They put up a gallant fight but were crushed by the arrival of a large Turkish army. The Turkish Government ordered King Nikola to make peace at once. The dismay of the tribesmen whom he had promised to stand by till they were free was piteous. They were commanded to return at once to their burnt villages but refused. The situation was very critical and the Montenegrin Government asked me to act as intermediary. They made it a condition that I should go with them. Mr. Charles Crane gave me £200, I raised more money and spent an arduous winter in relief work.

Then came the Balkan wars of 1912-13. By their cunning policy the Serbs had cruelly tricked the Albanians. They had separated them from the Turks and used them to drive the Turks from Kosovo. Far from fulfilling their promises to help the Albanians to liberty, the Serb and Montenegrin armies fell upon them with ferocity. The Albanians were trapped and unable to obtain ammunition from either side. The Serbs ruthlessly massacred wholesale. In Montenegro, at the inn dinner table I heard a Serb officer boast how his men had slaughtered men, women and children of the Luma tribe. “You must kill the women,” he said, “they breed men” and laughed till he choked over his beer. The Montenegrins cut off the lips and noses of prisoners and the dead and showed them as trophies, and burnt and looted. They boasted that when they took Scutari they would cut the throats of its inhabitants. The sad news came that Janina had fallen. Ismail Kemal, the Albanian leader in the south, appealed to the Powers and proclaimed the Independence of Albania, on November 28, 1912, at Valona. The claim of Albania was recognised and the Montenegrins were ordered to withdraw from the siege of Scutari. They obtained its surrender by means of a Quisling. Essad Pasha Toptani, a man detested save by the men of his own clan, was an officer in the Turkish army within Scutari. Terms were offered him through the medium of the Italian Consulate in Scutari. He and his men would be allowed to march out fully armed and he should be made Prince of a small Principality if he could contrive the surrender of the town. Essad then murdered the Turkish commander, Hussein Riza Bey, and admitted the Montenegrins just as the mountain men, who perceived too late how they had been tricked, were about to march to the town’s relief. The Montenegrins set fire to the bazaar and looted it. The Powers ordered the Montenegrins to clear out. They made a last and strange attempt to hold it. Petar Plamenatz, who had been made Governor, offered me the Governorship of Scutari - he to be nominal and I actual Governor - if I would persuade the tribesmen to ask for Montenegrin rule. “They will follow you,” he said, “speak the word, I implore.” He offered bribes. “Impossible,” said I. “But why?” “Because,” I said sternly, “I have been lied to too often.” He showed no anger. He said, “Alas, alas, Mlle. This time I swear I am telling the truth.”

An international naval force steamed up the river and as Admiral Burney landed the Montenegrin army marched out over the bridge. Albania was saved. I spent the winter feeding and clothing the half-starved Scutarenes and mountain folk.

The mountains were full of Moslem survivors, escaped from the lands taken by the Montenegrins and Serbs, telling tales of horror. Men were roasted by fires to make them accept baptism. Women herded into church and their veils torn from them. If the poor, dazed victims did not answer next day to their Christian names they were beaten and in some cases raped. Two wretched widows told how the Serbs had cut the arteries of elbows and wrists of their husbands and danced round while their victims bled to death. The grisly pantomime by which they described it made its truth clear. Briefly, the Serbs called this cleaning the land.

I did my best, too, to keep the peace among the foreign armies of occupation which arrived and had jurisdiction for some twelve miles round Scutari. Intrigue was rampant. Luckily in some crucial moments the tribesmen consulted me and I was able to get them to listen to the Admiral, which enraged some foreign officers.

Mr. Nevinson, the well-known war correspondent and Mr. Erikson, an American missionary, arrived and asked me to ride with them through Albania. We found perfect order kept by a small provisional government in every town and were welcomed everywhere. There was dread of Essad the traitor and hopes that soon the Powers would send the promised King.

We went to Ohrida, where large Serb forces were making ready to fight the Bulgars, and thence to Koritza, where we went to the schoolhouse. Heavy Greek forces occupied the town. Orders were being given that shop fronts were to be painted Greek colours. We were hailed as saviours. The Greeks held the telegraph lines and Koritza was cut off from the world. Save us from the Greeks we were implored. We visited the Greek commander, Colonel Kondoulis. He made no concealment of his intention not only to keep Koritza but to take the whole of South Albania up to Tepeleni, as he showed on a map. I protested that the lands were wholly Albanian and he had no right whatever to them. He replied, “Appetite comes with eating. We have eaten and shall eat more!” I said, “He that eats too much, gets the bellyache.” Nevinson said, “Take care, those fellows are furious.”

On returning to the schoolhouse - the Greeks had closed the school - we learned that Greek soldiers were making a house to house visit, ordering every inhabitant to come to a public meeting to vote for what form of government they wished. This was obviously arranged to impress us. Lest we should be made fools of and put on the platform with the Greeks, we went out and the officer sent to fetch us was too late. We arrived late at the meeting. Surrounded by Greek troops, the populace was said to have voted unanimously to be Greek and a telegram to that effect was sent to the Ambassadors’ conference in London. From both without and within the town we were begged to save them. We hired a guide and started on a two and a half days ride over rough mountain tracks to Valona which was in Albanian hands. Nevinson drafted a telegram explaining how the Greek vote had been obtained. Koritza was allotted to Albania and saved. At Valona we were met with a deputation of fine fellows from the Chiameria, also occupied by the Greeks, who begged earnestly to be saved but their prayer was in vain.

I left Albania at Christmas, 1913 and returned to Durazzo in April, 1914, where the Powers of Europe had appointed the Prince zu Wied as King. Why they agreed to choose him is a mystery, since France, Russia, Italy, the Greeks and the Serbs had agreed together to expel him and permit no German influence in Albania.

Wied was a well-meaning man but was never given a chance. He fell into the hands of the traitor Essad Pasha, who went to meet him and so gained his confidence that he made Essad his Minister of War. I landed at Durazzo to find a whirlpool of intrigue. The French Commissioner, a Polish Jew born in Bosnia (Kralewsky), told me that France would never permit an independent Albania; a Russian journalist and Dr. Dillon were backing Essad. I had a long talk with Wied and begged him not to trust Essad but to make a tour of the country with me. He hesitated too long. Essad as War Minister had control of the arms; he armed the men of his own district and also a large force of refugees from Dibra, which had been given to the Serbs. They were told that if they would expel Wied, Dibra would be returned to them. They rose, the signal for attack being given by an Italian, Colonel Muricchio, waving a red lantern at night. The British Vice-Consul saw him and he was arrested. So was Essad, who ought to have been court-martialled and shot. The Italians made a great uproar, Muricchio had to be released and Wied feared to act. Each of the Powers had a warship lying off Durazzo and Essad was put on board the Austrian warship. The Italians claimed him and cleared decks for action. The world war might have begun then had not Austria released Essad, who was taken by the Italians to Rome, feted and decorated.

The attack on Durazzo was a failure in spite of Italian efforts. The town was well defended by the little body of Dutch gendarmerie appointed by the Powers as Wied’s guard. The rebels sued for truce but hardly was truce made when there came news that the Greeks were invading South Albania and that Koritza was threatened. Sir Harry Lamb, the British Commissioner, sent me to Valona to investigate. It was too true. The Greeks and Serbs had planned a simultaneous attack. The refugees were streaming down to the coast. Valona was thronged. Under every tree or shelter for miles around, men, women and children were falling exhausted from a flight for life from their burning villages. The detachment of Dutch gendarmes who were in charge of Koritza had resisted till overwhelmed by superior forces and then had fled with the rest. They gave terrible accounts of the sufferings and deaths that occurred in the rush over the mountains.

Athens, when remonstrated with, denied complicity and declared it to be a local rising of so-called ‘Christian Epirots’ against the Moslems. This was quite untrue; the local Christians did all they could to aid their Moslem brethren. As Sir Harry Lamb said, the so-called Epirots were in fact Cretans. The leader was a Greek, Zographos.

An International Committee, of which I was a member, toiled to save the starving, suffering people. I shall never forget the miserable children dying under the trees. I obtained but very little condensed milk and there were at very least 50,000 refugees. A small ration of bread per head per day was the most we could do.

The Greeks were said to be approaching Valona. Where the army was we did not know. Athens continued to deny its existence. So I went myself two days’ ride up country to spy its position. Not far from Tepeleni on the opposite side of a deep valley when I crawled along the mountainside, I saw through field glasses, a large military camp with soldiers in khaki, tents and horses, as unlike a band of local revolutionaries as could well be imagined.

I returned in hot haste in one day, hoping to put pressure on Athens, and found that Russia and Germany had declared war. The Great War had begun. Austria’s declaration of war on Serbia was greeted with wild joy by the Albanians. The Serbs would be justly punished for the murder of the Archduke and Kosovo would be restored to Albania. We were cut off from all news. I crossed to Brindisi to get news, meaning to return if all was well and learned to my dismay that we had declared war forty-eight hours earlier. There was nothing for it but to return to England.

The Serb attack on Albania ceased ... the Italians landed at Valona and stopped the Greek advance ... the French occupied Koritza, proclaiming a Republic. During the war, though Albania had been declared neutral and independent by the Powers, it was entered by Serb, Montenegrin, French, Italian, Austrian and British troops. The Prince of Wied left on September 3 and Essad returned. By now the rebels saw how they had been tricked and telegraphed to Wied to return; he never did.

In April 1915, the British Government made a secret treaty by which Albania was to be divided between Greece and the Serbs, Essad to have his Principality. He acted as French agent all through and was well paid. The secret treaty was published by the Bolsheviks in 1917. Colonel the Hon. Aubrey Herbert formed a strong committee to struggle for Albania’s independence: Sir Samuel Hoare, Lord Moyne and Lord Harlech were members of it; I was Honorary Secretary. We had the support of Lord Cecil and later of Lord Balfour. After much hard work Albania was again made an independent state and a member of the League of Nations but unfortunately the Serbs were permitted to retain territory with some 800,000 Albanians and the Greeks also retained the wholly Albanian Ciameria.

Both Serb and Greek reckoned the Moslems as Turks, expropriated them and expelled them in numbers, penniless, to Turkey. Not a single Albanian school has been provided for those that remain. Their numbers have been so reduced as to make them powerless and they have been deprived of civil rights in Greece.

When I returned to Albania in 1921, a council of three Regents was ruling at the head of a Parliament. All seemed going smoothly; there was no national debt; Essad dared not claim his principality and to make sure that he should not do so, a young Albanian shot him in Paris, where he was living on French money. The outlook was hopeful and there was perfect order.

But oil was the undoing of Albania. It was believed to exist in large quantities. The wise priest Fan Noli thought it better for Albania to remain poor for a time than to grant large oil concessions to foreign Powers. Others favoured getting rich quickly. Ahmet Zogu of Mati, now known as King Zog and Fan Noli’s rival for the Presidency, promised a big concession to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and one to Italy. He obtained the support of Great Britain and the Anglo-Persian started boring.

In memory of her son, Aubrey Herbert, Elizabeth Lady Carnarvon started her noble work. She equipped a hospital at Valona, built and equipped a library, sent a scoutmaster to start boy scouts, which were very popular, and began anti-malarial work. British officers were appointed to train the gendarmerie. All looked well. Alas the Anglo-Persian found no oil worth working and withdrew. Italy, on the contrary, found good oil. Had we obtained the concession which the Italians did, Albania’s fate would have been very different. As it was, it became Italy’s sphere of influence.

The boy scouts were first suppressed and finally the British officers dismissed. Italy undertook to finance Albania and to make roads and bridges. Albania, which at first thought of Italy as a protection against Greeks and Serbs, became uneasy as Italy dug her claws in deeper and deeper. Some attempts to resist, made by the rising generation, many of whom had been educated abroad, were suppressed.

Then came the fatal Good Friday, when we all looked on and let a huge mechanised force overwhelm the little land and presented Italy with the control of the Straits of Otranto. At Durazzo, the gendarmerie and the cadets put up a brave fight. But the warships bombarded the tiny town and forced a landing. A pathetic incident was that when planes flew over Tirana, the populace thought they were English planes coming to their rescue. But they dropped leaflets saying that if further resistance were offered, the town would be destroyed. Having no anti-aircraft guns - none could be offered.

Very briefly this is the sad tale of a small and fine people who want only to live their own lives on their own land. Should any further dismemberment of their lands take place, they are threatened with extinction, for neither neighbour has shown them any mercy. In the years when I lived among them, I found the Albanians loyal, grateful and kindly. That they are highly intelligent is proved by the fact that those who have managed to come to England for education have taken good degrees at the London University. Their beautiful silver work and fine embroideries show them to be the artists of the Balkans. Do not let them be offered up as a human sacrifice either to appease our foes or propitiate our Allies.

[first published in: The Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain, vol. XXXI, 1939-1941. Reprinted in: M. Edith Durham: Albania and the Albanians: Selected Articles and Letters, 1903-1944. Edited by Bejtullah Destani (London: The Centre for Albanian Studies 2001), p. 193-204.]

TOP