| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

![]()

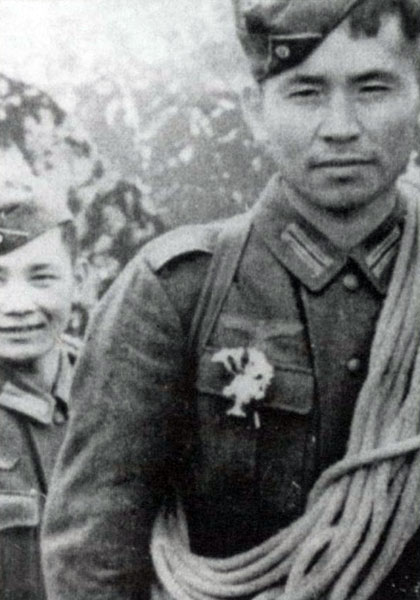

Fred Brandt in 1944.

![]()

Fred Brandt in 1944

(Photo: National Archives, London).

![]()

1944

Fred Brandt:

With the Partisans in AlbaniaBorn in St Petersburg (Russia) and raised in Latvia, Dr Fred Hermann Brandt was a German military intelligence figure in the Second World War. As an entomologist, he had travelled to Iran in 1937-1939 to study and collect butterflies and moths, and published several scholarly articles on the results of his expeditions. In the Second World War, as a member of the German Wehrmacht, Brandt trained as a counter-espionage agent and headed a Brandenburg Battalion in 1939-1940. He was initially seconded to Afghanistan, nominally as part of a “leprosy research commission,” where German intelligence had infiltrated the Pashtun tribes and hoped to organise an insurgency against the British. In early 1944, Fred Brandt and several of his Tajik men were sent by the Wehrmacht to northern Albania to set up a base in Nikaj, in order to secure German withdrawal routes from the south. There he was in close and friendly contact with British intelligence officers. By early October 1944, having lost contact with German intelligence in Peja and Belgrade and having heard that many German officers were being arrested and shot as traitors by the Nazi leadership, Brandt chose to accompany the British officers to Lezha and by boat to Bari as a prisoner of war. In an article on him in the British periodical “Sunday Pictorial,” published in 1957, long after the Second World War, Fred Brandt was called “the crafty butterfly colonel. He pretended only to want to catch butterflies when in reality he was Colonel Brandt, an enemy master spy, trying to close a net of death around the British agents… This spider was a master agent of the Nazis, one of the most incredible men in the murky wartime history of espionage and treachery.” In 1973, Fred Brandt wrote and published the following report on his amazing activities in Albania.

The Valbona Valley

(Photo: Robert Elsie, July 2011).

My superior officer in Peć [Peja], an intelligence captain, explained to me that he had received orders from Belgrade to set up a base in the Albanian Alps west of Djakovica [Gjakova]. This was to prevent the British officers of the Intelligence Service from providing the Albanians with weapons and materiel and from encouraging them to cut off our supply routes to the south and to blow up a chrome mine that was important for the war effort.

I was to set up and maintain this German Wehrmacht base in the Albanian Alps with some Tajiks.

From Peć it was about 75 km to this harsh mountain range. The base was to be set up deeper in the mountains, on the other side of a 1800 m. pass. The territory leading to the range consisted of thick forests stretching 30 km from the Valbona River. It was on the other side of this torrent that the stony cliffs of the Albanian Alps rose.

There were only narrow paths in this region, usable at most by mules. The base would therefore be two full days march from Peć, a factor that created the first problem – supply.

Before expressing my views on the plan, I asked my superior for permission to scout the territory. He agreed.

I set off in the first days of March 1944 with six Tajiks and an Albanian from Gusinje [Gucia] in Montenegro to reach the northernmost part of Albanian Alps. Our weapons consisted of seven submachine guns, seven pistols and six hand grenades each. The Albanian had an Italian carbine and we had sufficient ammunition.

First of all, we got over the 2000 m pass that marks the border between Montenegro and Albania and that was still covered in seven metres of snow at the time. There was such a snowstorm on the icy sections of the pass that our breath froze. After a fifteen hour march, we arrived in the narrow valley of Theth where I was received hospitably by an Albanian I knew. From here I wandered around the snowed-in countryside, back and forth for three weeks, much of the time without proper paths. It was at this time that I learned that the leader of the partisans, a force of some three thousand men, was an Albanian called Nik Sokol. I was informed that a British officer was staying at his headquarters that were situated in a rocky part of Curraj, in Nikaj-Mertur. Nik Sokol had established his eyrie up in the cliffs.

Tajik soldiers in Albania in 1944.

I now knew where I had to go. It was only after meeting Nik Sokol that I would know whether it would be possible to set up the base in the Albanian Alps, as ordered.

After two more days of exhausting marches – at times we had to make our own way through the deep snow – I arrived in the Valley of Nikaj. Nik Sokol’s house was situated on the opposite side of the valley, high up in the grey Hekura Cliffs, almost at the tree line. I spent a further two days trying to find a guide to take me up there, but none of the Albanians was willing to go with a German soldier and visit the mighty men. Finally I decided to go on my own. I made a show of laying all my weapons in front of the church of Nikaj so that everyone could see, and set off to meet Nik Sokol. It was already evening when I departed and crossed the Curraj bridge and it was pitch dark by the time I reached the first houses on the other side. There I succeeded in persuading an aged Albanian to accompany me.

We reached the house of Nik Sokol at about midnight and asked to be let in. I was sitting on the rug beside the fireplace when Nik Sokol’s wife, a Serb, came in and explained to me that her husband was not at home. She asked what I wanted. I stated that I had come in friendship and needed to see her husband. After midnight, two partisans arrived. They said they would take my message to Nik Sokol and that I should wait there for them.

The two partisans came back the next morning and told me to follow them. The march down into the valley lasted almost an hour until we got to an isolated farmhouse that was swarming with heavily armed partisans. I was taken into the guestroom where Nik Sokol was sitting near the fireplace. There were about a dozen partisans, his subordinate officers, squatting on the two sides of the room

In accordance with Albanian custom, I firstly received two cups of strong Turkish coffee as a sign of welcome. Nik Sokol drank with me. He then inquired as to what I wanted. I asked to speak to him alone as I had an important message for him and he could then decide for himself whether he wanted to inform his officers about it or not. He made a brief gesture and the men all withdrew. When we were alone, I told Nik Sokol that I had come on orders from the German Army command in Belgrade to set up a base in Nikaj. I did not want to come as a foe but as a friend, and I would be of any assistance I could. I would regard the Englishmen as his guests and would not attack them or endeavour to drive them out.

It was not all that simple to explain. We went through everything in detail until we had reached agreement point for point. Finally Nik Sokol gave me his hand in sign of peace. He then took off my military cap and put his white Albanian felt cap on my head, adjusting it skilfully towards the back. I was to wear this white cap in the mountains so that all the Albanians could see that I had come as a friend.

Before his officers came back in, I advised Nik Sokol not to fight German troops and get himself killed for the British. It would be better for him to pretend he was fighting, to shoot around in the air here and there, and then to tell the British how many Germans he had killed and how many vehicles he had destroyed, etc. In return, we would drop more weapons in, and anything else he required. He would then have no fear of German reprisals. Nik Sokol stared at me in amazement without saying a word. I could sense that he had taken my advice to heart.

Path over Valbona Pass at 1900 m.

(Photo: Robert Elsie, July 2011).

When the officers returned, Nik Sokol explained to them that I was his and their guest in Nikaj and would be setting up a base with my six soldiers that would be of advantage to everyone. The men were enthusiastic and many a fraternal kiss on the cheek was exchanged. However, Nik Sokol did not tell them what I had advised him to do. That was to remain our secret.

A ram was then slaughtered and a feast prepared. It was late at night when I got back to my men at the church of Nikaj. I had the two partisans with me who had accompanied me to Nik Sokol that morning. He had given them to me as permanent companions and fighters.

The next morning we marched eastwards with them and then headed southwards to get around the mountain along the Drin. The mountain passes were still covered in snow and were difficult to cross. We reached the village of Paja that evening where we were expected and well received by the local bajraktar, a friend of Nik Sokol’s. Another feast was held, with eating and drinking until late into the night. The next day we continued northwards along the eastern slope of the mountain until, in the evening, we got to a bridge over the Valbona. The river was swollen and could only be crossed there. There was one solitary house at the bridge that served as a little shop. When we approached, shots were fired out. It was dark by then so that no one could have been aiming directly at us. Our two partisans cried out to explain who we were and the firing ceased. When our men had explained to them, partisans, too, that we were friends of Nik Sokol and thus their friends, we were hospitably received, and spent the night there.

Early next morning we crossed the wobbly bridge over the Valbona and continued through the snow-covered forest of Bytyç until we got to Dega. There had been a British base here in February, but the officers of the Intelligence Service had managed to get away in time. It was now up to me to join the ends of the net that were rolled together here and that now covered all of northern Albania. I already had one end of the net in my hand – in Nikaj!

In Dega where were nothing but ruins left – not food or shelter to be had. We therefore had to continue eastwards through the deep melting snow over swollen rivers and torrents. It was only in the evening that we reached a settlement where we could get some food and shelter. The next day I was in Peć again. My reconnaissance trip, my scouting around, had lasted three weeks.

I reported to my superior what I had seen and experienced and what I had accomplished. He agreed with everything. I received orders to set up the base in Nikaj and was given complete freedom to act. In early April 1944, I then set up the base in Nikaj with six Tajiks, in a house that Nik Sokol had evacuated for us and given to me. We had at our disposal one machine gun, one light mortar, seven submachine guns, seven pistols and ten hand grenades per person.

On Easter Sunday I first of all attended mass at the Catholic church of Nikaj, accompanied by my Muslim subordinates. We then clambered up to Nik Sokol’s house to pay him an Easter visit. There, I met Major Neel, the head of the [British] Intelligence Service in the region. Nik Sokol and his men were sitting around a low (ca. 20 cm high) table with the British major and his interpreter, an Italian sergeant who spoke perfect English. We left our weapons leaning against the wall and sat down with them. I was given a seat right beside Major Neel. We were both guests in the house of Nik Sokol so no hostility could arise. After a courteous handshake, Major Neel filled our raki glasses with whiskey and we drank to one another’s health. This set the pace for further “friendship.”

I met Nik Sokol again a few days later. He brought up the advice I had given him not to fight German troops but to simply pretend to do so and deceive the British. He stated that he was willing to do so if I informed Major Neel that I had no objections to parachute drops in Nikaj and the surrounding region as long as the material dropped in was for Nik Sokol. I agreed.

Fred Brandt (left), British officers

and Tajik soldiers in 1944

(Photo: National Archives, London).

I was picked up the next night by “my” two partisans for another meeting with Major Neel. I assured him that I had no objections if he wanted to order material from Bari and give it to Nik Sokol. I said that my men and I would even help to bury the parachutes. Nik Sokol had told me that this was a great problem. The containers were often spirited off by partisan “irregulars” and sometimes more than half of the material was lost.

The next parachute drop went off without a hitch. There were no problems and we even managed to recover the parachute with gold and mail for the British officers. I was the one to mark out the landing site for the drops with bonfires so that the pilots could find the right approach at night.

This was just the start. Later I sat around with the men when the goods were being distributed. I also made friends outside of Nik Sokol’s unit and advised them, too, not to get themselves killed for the British, but to live off them. However, I was not able to get into contact with the Albanians in a blood-feud with the Russian legionaries in Peć, who were subordinate to my intelligence captain. The reasons for the feud would go beyond the scope of this report.

In mid May 1944, Major Neel suggested that I could accompany him to a meeting of Intelligence Service officers in northern Albania. I had little time to consider the proposal because they intended to depart that very evening. I took two of my Tajiks with me, and “my” two partisans. We were accompanied by Nik Sokol with five men, and by Major Neel and his interpreter. We were all heavily armed when we set off from Nikaj. After a march that lasted several days, mostly at night, we got to the region of Fusha e Lurës, where we were given guides who accompanied us eastwards into the mountains, over the Black Drin. The British base was in a lonely Albanian home which was full of weapons and other materiel. There were also two wireless operators. The other participants arrived the next day. They had been held up by some Albanians who had recognised them and inform the German authorities. As a result of this, an SS unit suddenly turned up and began to search the village that consisted of isolated farmhouses all at a good distance from one another. We fled from our house and hid up in a scrub forest, observing events with our binoculars. It was cold out and we were soon drenched from the drizzle.

Evening finally approached. The SS men down in the valley, exhausted from their fruitless search, were looking up at the unchecked farmhouses on the slopes. They shrugged in resignation and departed, and we were soon back in our warm asylum. The next day we were joined by a further eight British officers. It was a curious mix of humanity: Englishmen, Germans, Tajiks and Albanians, whose fate had been linked for a short time. We came to an understanding in no time. I promised to protect Major Neel and his men from danger, in particular from bands of Albanian thieves. I wanted, for my part, to reinforce my base in Nikaj, but this depended on my superior in Peć, and on Nik Sokol. I expressed my clear and unequivocal opposition to any combat activities, even indirect, involving German troops. The British accepted this position.

We departed and went our various ways two days later. Major Neel and Nik Sokol went westwards to meet some Albanian friends of theirs. I set off northwards to return to my men. We did not know the area and it was full of partisans. The British officer stationed there, a major, accompanied us with his men to north of Bihac [Bytyç?]. We got back to Peć via Prizren and Djakovica where I reported to my superior and briefed him about everything. He agreed to my contacts with the “competition” and said he would inform Belgrade. He also asked Belgrade about reinforcements for my men.

A week later, a lieutenant colonel of our intelligence service in Belgrade arrived in Peć. I briefed him on everything. He was convinced that my orders from Army Command could only be carried out in the manner I described. He gave me full freedom of action and approved a further twenty Tajiks for Nikaj. “The British are quite right,” he noted, “you cannot man a base with six individuals!” His final words were: “Keep up the good work!”

Major Neel turned up at the end of June with another IS officer, Lieutenant Hibberdine, who could speak good German, and with a wireless operator to maintain ties with Bari. At the end of July, at the request of the British and with the approval of my superior, I set up a joint forest camp with them. They were under my protection here. Nik Sokol and some of his partisans were camped out in the vicinity. They were fed by the British. I had ordered food and supplies to be brought in on mules in a strenuous march from Peć, but now the route back was block by partisans. As such, we too were now being fed by the British! In addition to this, Major Neel gave me three machine guns, two mortars, twenty-five submachine guns and a lot of ammunition, enough for a long period of struggle with the bands of communist partisans. We spent all of August at the camp. Major Neel then received orders to make his way to the Skutari [Shkodra] region. I stated that I was willing to accompany him with my men. “I have never felt as safe and secure in Albania as I have under your protection,” he replied. For this, he was obliged to accept my control over his activities. For as long as we were together, Major Neel was thus unable to engage German troops in fighting anywhere. Nik Sokol and his men also came with us.

In early September, we set up camp at a base 1600 m. high in the mountains of Shillaku [Shllaku], north of Skutari. A few kilometres below us was a longish glade in the forest that was suitable for air drops. Around this period, Major Neel received orders to destroy a German fuel depot and to blow up a bridge over the Drin. He could only carry this order out with help from the Albanians. I, however, had forced them to take a decision, either to continue being my friends or be the friends of the British. They opted for me. My Tajiks also refused to engage in combat against German troops, although Lieutenant Hibberdine did all he could to convince them to join his side.

Influential Albanian partisan leaders appeared more and more frequently in the glade near our camp, that had a good source of running water – a rarity in this arid region. I was down there on an almost daily basis and was no longer considered as being under the protection of Nik Sokol, but as the commander of the British camp. Even the British came to regard me as their “colonel.” I was treated on an equal footing with the rest. I soon acquired a certain following among the bajraktars and even Nik Sokol stated with pride that he was my friend!

There was one thing that all the Albanians agreed upon – the need for the creation of a national army of the north to oppose the communist partisans forming in the south of the country. But where were they to get weapons and equipment for such an army? I promised to ask the British. I had come to feel very attached to these Albanians and suffered with them in their situation.

That evening, at dinner, I spoke to Major Neel, explaining to him what needed to be done. After the withdrawal of German forces, a national Albanian government would have to be created and supported. He reacted with enthusiasm and promised to contact Bari about the idea straight away.

The reply came two days later – complete agreement! The northern Albanians would receive everything they needed, even weapons, and we were to inform British headquarters of what they required most urgently. The next morning, I took the good news to the Albanians in the forest glade. They were jubilant!

The next step was to choose a leader for the national resistance movement. The choice fell upon me. I was acceptable for all sides, and was neutral. The Catholics regarded me as one of theirs. The Muslims regarded me as a follower of Allah, and I was even a friend of the British, their commander, and indeed a “colonel.”

About this time, I received warning from the Albanians that the SD [Nazi Security Service] had put a price on my head, dead or alive. I was not surprised. I had been hearing reports on the radio day after day and knew about the wave of arrests of German intelligence service officers. Even though I was a small fry, nothing more than a private first class, I had been consorting with the British for months. What proof did I have that I was working under orders? Nothing at all. I had no idea where my superior was, now that Peć had been evacuated, and who knows whether the lieutenant colonel in Belgrade would even remember me?

The Albanians were in elated spirits for about a week. Groups of them arrived from throughout the country and wanted to fight with us. The new armed forces were beginning to rise. Nik Sokol had advanced with his men to the suburbs of Skutari. In all, we now had over 2,000 men on our side, all waiting for the British to drop materiel. Yet nothing arrived but a message for Major Neel to proceed to the coast near Alessio [Lezha] with the Albanian leaders to board a British naval vessel that would take them to Bari for an important meeting. We were guaranteed safe passage. We were on the point of departure when a second message arrived. We were not to proceed to the coast but to Montenegro, to the Berane area, where there was a British airfield. We would be flown to Italy from there. The Albanians of course all refused to go to Montenegro, to the Serbs, their sworn enemies. As such, only Major Neel, his Italian interpreter and I with three of my twenty-six Tajiks set off northwards. After days of marching, we reached Gusinje. The British had by now abandoned the airfield near Berane because of the German troops that were withdrawing through the region. The situation there was so confusing that we decided to return to our camp in Skutari.

There we received word from Bari that all the promises made to the Albanians had been withdrawn. They would receive neither weapons nor food from the British. It was all over! Major Neel received orders to leave the camp near Skutari immediately and make his way to the Adriatic coast. My Tajiks and I were allowed to decide for ourselves whether we wanted to accompany him. If we did, we would be guaranteed the status of prisoners of war. This was in early October 1944.

One last time, I made my way down to the forest glade to inform my Albanian friends of what I had heard. It was a bitter errand and a painful farewell now that all of our common hopes had been dashed. A farewell forever. I could do no other than accept the British offer. I could not stay on all alone in a country that was about to be torn apart by civil war.

A few days later, we reached the coast, south of the Drin delta, in an isolated reach of lagoons and marshes. Despite substantial technical difficulties, we managed to get on board two small naval vessels. Two national leaders of the Albanians came with us to try, one last time, to get the British to change their minds. But their mission failed, too. There was no change. The British all departed, and the Albanians were left to fend for themselves. I stood at the railing and watched the Albanian Alps in the east recede into the haze. I had spent eight months there as a German soldier, as a Brandenburger, and had live with the partisans, carrying out the orders I was given by my superior.

[Fred Brandt: Bei den Partisanen in Albanien, published in the periodical Die Nachhut: Informationsorgan für Angehörige der ehemaligen miltärischen Abwehr, Munich,Vol. 23-24 (1973), p. 21-30. Translated from the German by Robert Elsie.]

TOP