| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

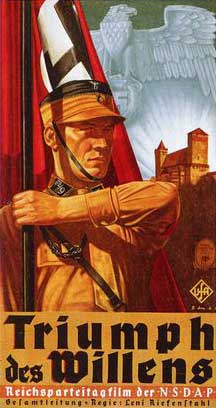

Triumph of Will.

Nazi propaganda film poster, 1934.

1945

Final Report

of the German Wehrmacht

in AlbaniaThe Italian administration of Albania during the Second World War collapsed in September 1943. Units of the German Wehrmacht immediately occupied the country to prevent an Allied landing. The Germans restored the formal independence of Albania and, to an extent, respected the country’s sovereignty. Despite this, Albania was effectively occupied by the Third Reich for over a year. In October-November 1944, German forces withdrew from Albania and began their long march through the mountains of Bosnia back to Austria and Germany. The author of this fifty-page report was a member of the so-called Administration Group of the Wehrmacht that carried out various administrative and technical duties during the occupation. He describes the conditions in the country in 1943-1944 as he saw them and provides an overview of the political, administrative and economic situation. This unique report on German-occupied Albania by a Nazi official seems to have been drafted in February or March 1945, i.e. after the withdrawal from the Balkans and only a few weeks before Germany’s capitulation.

I. ORGANISATION OF THE GERMAN ADMINISTRATION

AND ITS EVOLUTIONBasic Position of the German Administration in Neutral Albania

There was no actual German military administration in Albania. Those officials of the military administration who were working in Albania had duties that were quite different from those in France, Belgium or Serbia.

German policies on Albania were guided by the basic principle that Albania was to be respected as an independent and neutral country. There were good reasons for this. As the only primarily Muslim state in Europe, Albania required special consideration within the framework of Germany’s policies towards the Islamic world as a whole, particularly with deference to Turkey, and had to be treated with special care and consideration at the political level, far more than its importance as a country would have warranted. One could, however, ask the question as to whether this principle that was respected right to the end, was not overdone. At any rate, it was a determining factor for German administrators who had Albania’s future in their hands and it largely determined the scope and limitations of the Administration’s activities.

The Occupation of Albania

Albania was occupied by the German 2nd Armoured Division as of 9 September 1943 following Italy’s treacherous change of alliance. There was no major enemy resistance to be put down and, as such, the towns and roads were taken with relative ease and speed.

The German General in Albania

Artillery General Geib was assigned territorial command. He initially had authority over Montenegro, too, but for political reasons, that country was soon made an independent entity. The office of the ‘German Commanding General in Albania,’ DGA [Deutscher bevollmächtigter General in Albanien], that was finally established in the country was set up as a division staff headquarters. Since the DGA did not actually have troops under his command, his position was weak from the very start.

Field Commands

In October 1943, three Field Commands (FC), Nos 1030, 1039 and 1040, arrived from Germany to exercise territorial authority under the DGA in the medium term from their final staff headquarters in Tirana, Prizren and Struga. The Prizren FC administered the region of Kosovo; the Tirana FC was mainly responsible for the coastal region of Old Albania, from Vlora to the Montenegrin border and including the region of Elbasan; the Struga FC was responsible for the eastern part of Albania bordering on Bulgaria. The southern tip of the country, that had been an eternal trouble spot since the Greek-Italian war was liberated temporarily during fighting in mid-summer 1944. A fourth Field Command was subsequently created from the three existing ones and included the southern region. Its headquarters were to be in Korça. It was set up but never became active in practical terms because event in the autumn superseded it.

Local Commands

The lowest level of territorial administration were the local commands in the major cities that, depending on the energy and dynamics of the commanders in question, were among the most crucial elements in the administration of the country. They were the only German institutions that had real close and reciprocal contacts with the population.

The Special Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Shortly after the arrival of the DGA came Military Administration officials to work under the general and the field commanders. Their activities were interrupted in November and December 1943 when they were withdrawn for political reasons. The Special Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for Southeastern Europe (Sonderbevollmächtigter des Auswärtigen Amtes für den Südosten) endeavoured, in view of Albania’s neutral status, to restrict German influence on the Albanian Government and on the Albanian administration wherever possible. Exclusive responsibility for the general outlines of German policy in Albania fell from this time onwards upon the Special Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Commissioner for Economy and Finance

As part of the Tirana Field Command, an office was created for a Commissioner for Economy and Finance [Beauftragter für Wirtschaft und Finanz], under the aegis of the German consul-general in Tirana, to deal with economic relations between the two countries and with the local financing of the Wehrmacht in Albania. The problem with this office was that, being subordinate to the German consul-general, later ambassador, it received its instructions from the Special Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Its work was also impeded by the fact that it had no German branch offices outside of Tirana. It was thus totally dependent upon the Albanian institutions and administration as, fearful perhaps of losing any of its autonomy, it only sought contact with the local commands in the countryside when this was absolutely necessary. The result of this was a not always profitable dependence on Albanian interests and views, which occasionally resulted in disputes with the military.

Return to Military Administration in Early 1944

In early 1944, the DGA brought the Military Administration back to Albania. Initially, only two high-level officials were seconded: Dr Westphal to work under the DGA and Schulze-Waltrup to work with the Tirana Field Command. Subsequently, Heimer was seconded to the Field Command in Prizren, and Von Carlowitz to the Field Command in Struga. Merten was also proposed for the Field Command in Korça. A few other officials were later added because of the increasing duties placed upon the Administration Group [Verwaltungsgruppe]. All of the military officials seconded to the field commands formed part of the Administration Group under the DGA.

Basic Duty of the Military Administration Officials

The new duties of the Military Administration officials were limited by the commander in charge of Military Administration in Southeastern Europe initially to observing the situation so that, should the Albanian state collapse, a replacement organization could be put in place immediately by using people with local experience.

The Actual Extent of Administrative Activities

If the Military Administration officials did not always adhere to this practice, it was because, where measures had to be taken in German interest, the Administration was forced to intervene under orders from the DGA because of the incompetence of the Albanian authorities. It is more than evident that it was exceptionally difficult to work without authorization from above and without an executive. Good negotiation skills were essential in attaining a proper division of labour with the other German institutions.

German Consul-General

The German consul-general, who was raised to the level of ambassador in June 1944 when relations between the two countries were intensified, confined his activities to discreet diplomatic exchanges with the Albanian Government and to consular duties. There was good cooperation with the passport and ID division where the Administration was responsible for the issuing of military laissez-passers.

Commissioner for Economy and Finance

More cumbersome were relations with the Commissioner for Economy and Finance. It was arranged that, wherever military interests were involved, responsibility would fall upon the DGA. This transfer of responsibility was, however, not clear enough in individual cases to overcome conflicts. The German military often accused the Commissioner of being too friendly to the Albanians and asked the DGA to bring things back into keel.

Commanding General of the 21st Mountain Army Corps

The Commanding General of the 21st Mountain Army Corps [XXI. Geb. A.K.], commander of the troops in Albania, first intervened decisively in the territorial administration of Albania when, in the spring of 1944, he called for the evacuation of a broad strip of coastline in the interests of sea defence. As events progressed and our military situation declined, the corps commander became more and more prominent in dealing with the country’s administration. When executive power was handed over to the commanding general in early September 1944, the DGA became his official subordinate.

SS chief Josef Fitzthum (1896-1945).Supreme SS and Police Chief

The Supreme SS and Police Chief, who had been seconded to Albania originally to build up the Albanian gendarmerie and police, tended from the very start to involve himself in the country’s administration in general. When the job he had originally been sent to do became impossible at the end of July 1944, he began intervening more and more in the management of domestic Albanian affairs. It was thus logical and consequential at the end of August 1944 that the two positions, that of DGA and of Supreme SS and Police Chief, be united and conferred together upon Gruppenführer Fitzthum.

Duties of Oberführer Gstöttenbauer

At this time, the Special Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs also sent a representative of his own to Albania to stimulate political activity. Oberführer Gstöttenbauer endeavoured to take control of all aspects of policy and administration, in close co-operation with the DGA.

Commanding General as Sole Territorial Commander

When in early October 1944 Oberführer Gstöttenbauer left Old Albania and shortly thereafter the whole country, with Gruppenführer Fitzthum and the German ambassador soon to follow, territorial command as a whole was transferred to the Commanding General of the 21st Mountain Army Corps.

Changes in Subordination for the Administration Group

This constant reorganization after the end of August 1944 meant re-occurring changes in the subordination of the Administration Group.

As the first official act in his capacity as DGA, Gruppenführer Fitzthum dissolved the four Field Commands to reduce staff and created the office of the ‘German Field Commander in Albania’ with full responsibility for territorial command. The Administration Groups were exempted from this staff reduction measure. The reason for this was that it was recognised that at least the German administration had to continue functioning at a time when the Albanian administration and services were collapsing. However, with the dissolution of the four Field Commands, the Administration Groups lost their organisational subordination. As a temporary solution, the head of the DGA Administration Group and the head of the Tirana Field Command were added to the staff of Fitzthum. The head of the Prizren Field Command was made subordinate to the local command there. The administrative districts of Tirana and Prizren remained unchanged. The area of the one-time Field Command of Struga had either been evacuated or was taken over by armed bands. For this reason, the head of the Administration Group there was transferred to Shkodra to take over the administration of that important town.

Mellin was made head of the 7th Division of the Corps in recognition of the fact that the Corps would, in the end, be the only command authority left. When the Supreme SS and Police Chief departed, Schultz-Waltrupp took over the 297th I.D. to secure Old Albania from about 40 kilometres south of Durrës, to the extent that it had not already been evacuated. Heimer was seconded to Kosovo to the SS Skanderbeg Division, but since this division soon fell apart and New Albania had to be abandoned, he never really assumed his post.

Co-operation between the Administration and the Troops

The re-subordination of the Administration Group to the troops was necessary and proved, under the circumstances, to be a good idea. Co-operation was excellent since the Administration Group, with its detailed knowledge of the country and people, was able to provide useful assistance. The troops recognised its value and requested that an official of the Administration Group remain with them until the very end. As such, after twenty days in Tirana under siege by armed bands, it was with the last army troops that Schulze-Waltrup departed from Shkodra.

Evacuation of Albania

In early December, the Administration Groups began their withdrawal with the troops on an exhausting evacuation through Montenegro and central Bosnia that lasted months and during which many men died. In early 1945 they reached Sarajevo. Dr Mellin caught typhoid fever on the way and died in Germany on 3 February 1945.

II. POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS

Early History of the German Occupation of Albania

German policies in Albania can only be understood if one knows something about the early history of the occupation there. Albania had been difficult for German observers to fathom since the time the Italians took the country over in the spring of 1939. Italy created a glittering façade to cover up the country’s rotten foundations. From the start, publications about Albania were one-sided. In an exaggerated language, they endeavoured to show that Zog’s reforms had modernised the country and that the Albanians were profoundly grateful to the Italians. After the occupation, official propaganda succeeded even better in convincing the world that the Albanians had accepted Italian rule and that the administration of the country functioned perfectly. This was easy due to the favourable impression that could be had by the casual visitor. The capital city, Tirana, now had some spectacular buildings to show for itself and others were being planned.

Italian Policies in Albania

In reality, Italian rule and the Albanian state were standing on feet of clay. The Italians endeavoured – logically from their point of view – to eliminate the strong Zogist influence in the administration by firing all the Zogist elements. In their personnel policies, the Italians gave the impression that they were consciously letting the local Albanian administration go to seed. The reason for this was that they wanted to demote Albania from the rank of a condominium to that of a colony. From an Italian point of view, this policy is understandable since it seemed to be the only means of transferring as large an amount as possible of Italy’s dense population to ancient Rome’s one-time breadbasket in the Balkans.

This policy had disastrous repercussions on the Albanian state. The semi-European, semi-Oriental administration of King Zog that had at least established a semblance of peace and order in this land of classic local feuds and thievery was replaced by an entirely incompetent staff who, in the following years, proved themselves to be unable to undertake any practical activity.

The Armed Bands during Italian Rule

While Italian policies had, consciously in part, led to the country’s collapse, order in Albania was more seriously perturbed by the swift spread of armed bands. Since the Italians were unwilling or unable to put them down militarily, despite all their occupation forces, they justified themselves by telling the outside world that the bands were all communist rebels. This was not true, at least for the early period of the struggle against the armed bands. At the start, their members were mostly freedom fighters opposed to the Italian invaders. It was only later that the Communists began pulling the strings and forcing the armed fighters more and more into the communist camp.

Exclusion of Foreign Observers

Since the Italians managed to prevent foreign observers from seeing behind the scene – no great difficulty in view of the tradition country’s inaccessibility – German observers often accepted Italian interpretations of events in Albania and saw the country through Italian eyes. When they occupied Albania, they assumed that there was a more or less functioning state, as there had been under Zog, even though parts of the territory were under attack from Soviet armed bands.

False Evaluation of Albania

The Germans made another mistake in policy by relying almost exclusively on the cast of wealthy landowners and beys and by underestimating the real forces and currents in the country. This was in a sense understandable since the landowners were the natural foes of the Communists – admittedly rare at the time – and were thus Germany’s born allies. This part of the population was made use of in particular because they were much easier to communicate with. Most of them spoke German or at least some other international language. Contacts with the masses of the population, i.e. understanding what was actually going on among them in the countryside was more difficult because of the language barrier. Even at the end of the occupation, there were probably no more than ten Germans who could speak Albanian.

Close contacts with the ruling class in Albania were facilitated in particular by the Albanian belief, during Germany’s zenith of power, that the German Wehrmacht would protect and defend their ancient economic privileges. In view of Germany’s close ties with the cast in power, the Communists used their influence skilfully by casting bait to the broad masses of the population and thus garnering influence among the underprivileged.

The Influence of Islamic Policy and Recognition of Albania as a Neutral State

The Germans misinterpreted the political realities of Albania and believed the road had already been paved for setting up an independent state. This endeavour seemed all the more propitious in view of Reich’s policies on Islam and its deference to Turkey. Right after the occupation of Albania, German relations with the Albanian executive committee that was to run the country until a definitive government could be created, were guided by the strict principle of the recognition of Albania as an independent and neutral country.

Regency Council under German

occupation, October 1943.

Definitive Albanian Government,

Regency Council, ParliamentAn Albanian Government was then set up to take over the administration of the country. It was assisted by the Regency Council, conceived as the representative of a head of state, and by the parliament. Democratic governance was allowed which, later, proved to be a detriment. On the one hand, constant infighting within the tripartite division of power impeded peaceful development and, on the other hand, despite German pressure, there was no one on the Albanian side with sufficient authority willing to assume responsibility for implementing German wishes and demands and for transforming them into reality.

Listing the ever-changing government administrations during the German occupation would mean lending them a significance they never really had for the country or for Germany. There were only a few figures of note who rose above the rather mediocre average.

Mehdi Frashëri (1874-1963).Albanian Politicians – the Frasheris

The primary figures were the head of the Regency Council, Mehdi Frasheri, and his son Vehbi. Right to the end, the Frasheris knew how to struggle through and sail with the winds and were, because of their adaptability, the most successful politicians in Albania. Despite their impeccable behaviour towards Germany, their attitude was eminently ambivalent. There is no doubt that, for every German wish and demand, they were in discrete contact with the Western Allies via Ankara, but they had and wished to have no contacts with Communist circles. Proof of this is the fact that, right to the very end, the Frasheris refused to be evacuated to Germany, even by plane, since they were secretly waiting for the often announced landing of the English. It was only when this landing did not materialise that they left on foot with German troops to escape from the advancing Communists. In kind German consideration for their situation, Frasheri senior and his wife were taken to Podgorica on a JU.

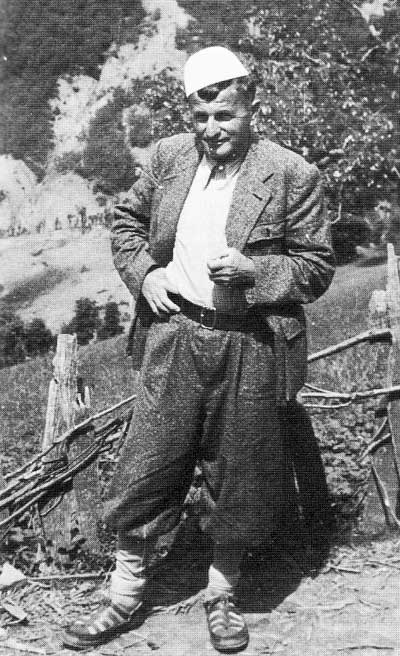

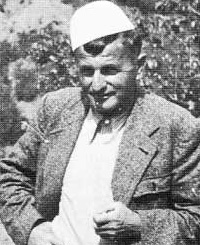

Ago Agaj (1897-1994)

in October 1943.Minister Ago Agai

Until mid-summer, in contrast to the above-mentioned inscrutable figures, the pillars of German policy were Minister Deva and Minister Ago Agai, both Kosovars. The minister of economics, Ago Agai was impeccable as a person, but was too doctrinaire to get any real work done.

Minister Deva

The minister of the interior, Deva had requisite power and energy to be an effective instrument of German policies. In the awareness that any government without executive power was no government at all and that an iron fist was always needed to get things done in Albania, Deva created his own personal bodyguard of Kosovars and brought them down to Tirana. These savages from the mountains exercised quite a reign of terror upon the capital city, at least by European standards, but in the final analysis they probably got the situation under control. It was perhaps unadvisable, but it was understandable that the German Administration often complained about the excessive behaviour of this group of Kosovars in early 1944.

Xhafer Deva (1904-1978).Deva’s Departure

Since the Albanians are in many ways very sensitive to political undercurrents, Deva’s adversaries soon gained the impression that he did not enjoy unconditional German support. In addition, as a northern Albanian, he was not that popular in Old Albania. The average Albanian, who sniffs at order and governance, felt ill at ease with his harsh ways. Thus, in the course of the spring and summer, all of Deva’s open and hidden adversaries rose in power. By mid-summer, the most useful piece had been wiped off the German chess board.

Deva’s attempts in his homeland to create a national movement friendly to German interests were without practical effect, in particular in view of the coming end.

Ibrahim Biçakçiu (1905-1977).

Prime Minister Bichaku

Mention must finally be made of Prime Minister Bichaku [Biçakçiu] who was personally a sincere friend of Germany but was incompetent in his public actions and without any sense of political instinct. Despite German warnings, he stayed in the country and was then shot by the Communists.

Parliament

Parliament exercised no visibly positive influence on the country’s development. Only on a few occasions did it endeavour to influence affairs and, in doing so, simply made a nuisance of itself.

Albanian Political Parties

The political parties, on the other hand, had substantial influence on domestic politics and developments.

The Nationalists

The nationalists, a collective term comprising government and mostly pro-German forces of various hues and colours, never managed to unite and form any organisation. As they were in disagreement with one another, they were never of any use for German policies as a party.

The Ballists

The Ballists who, at the beginning, seemed promising as a political grouping, were unable to take a definitive decision as to whether to support the English or the Germans. In their struggle against the armed bands, most of them initially supported Germany, but their leaders were supporters of England from the very start. Later, by mid-summer 1944, when England seemed to be losing more and more terrain in the Balkans to Russia, the Ballists lost influence almost entirely and were pretty well finished by early autumn.

Abas Kupi

(Photo: David Smiley, 1943).The Zogists

The Zogists gathered around Abbas Kupi, a political follower of Zog, who was in military readiness on his own in the Italian period and was able to maintain a relatively strong and orderly military force. In the summer of 1944, the Zogists seemed to be the ones to be profiting from the collapse of Balli Kombëtar and to be turning into the major force in the chaos in Albania. They profited from the widespread sympathy for Zog in the country because the population was of the view that, despite all of its failings, the half-despotic, half-modern rule of King Zog was the only solution for Albania. Abbas Kupi, however, lost his prospects because he never definitively took sides in the fight between the Germans and the Communists. In typical Albanian fashion, he tried to maintain relations with both sides and, wherever possible, deceive them. The consequence of this wishy-washy policy of his was that he lost all of his influence during the evacuation and seems to have been forced to flee to Italy.

Mehmet Shehu (1913-1981).The Communists

The Communists were the ones who profited from the situation. The few Russian-oriented masterminds – foremost among whom was Mehmet Shehu, a capable military leader of recognized qualities, though siding with the Soviets – managed to denationalise the armed bands in the first half of the year and put them increasingly under Soviet influence. It is interesting to note in this development that, in the early weeks of summer, the red Albanian flag of Scanderbeg, elsewhere brandished with the hammer and sickle, was being burnt in the so-called Soviet republic set up in southern Albania. Since this one-sided orientation to Soviet Russia initially raised quite an outcry, the Communists skilfully changed their course and subsequently led the struggle under the slogans: “The Fight against the Foreign Invaders” and “Modern Social Reforms”. People joined them in droves since they promised they would give free property rights to the peasants on their farmland; jobs, salaries and influence to the large intellectual proletariat, being mostly schoolteachers; and sexual freedoms to the young people living in the constraints of fossilized traditions. Since revolutionary movements always attract the most active elements in a country, by the beginning of autumn when open war with the German Wehrmacht had become inevitable, the Communist movement had at its disposal a strictly controlled and dangerous following that was resolved to carry through with a general armed uprising.

Until the autumn, these forces, some of which were still friendly and others hostile, held one another in equilibrium. The Germans, however, found two useful factors that they could use to influence events.

Albanian Sympathies for Germany

In Albania, there was surprisingly widespread support for Greater Germany. This dated from the years before and during the [First] World War and derived from people who had heartily approved of Austro-Hungarian policies in Albania in war and peacetime. Italy, for its part, despite its alliance with Germany, did all it could to interrupt this link, but attachments to Germany were only covered over and not broken off.

Germany as Albania’s Only Altruistic Ally

In addition to this, the foreign political situation of Albania in the Balkans made it evident to all objective political observers that Albania’s only altruistic ally and protector was Germany. The creation of Greater Albania by the addition of the fertile region of Kosovo was made possible by the German conquest of the Balkans. It was only with the return of Kosovo that the country was put on a more or less solid economic footing, and this enabled it to live independently without forever being under the heel of other countries. Any logically thinking person understood that this order of things could only be maintained in the long term if Germany remained the dominant power in the Balkans, because the Serbian people would never willingly have given up the fertile plains of Kosovo.

Albania’s Significance for the Other Foreign Powers

Aside from Greece, Albania is the only non-Slavic country in the Balkans. Any Slavic confederation in southeastern Europe would inevitably lead to its ruin. With the collapse of Italy, and in its struggle for survival as a nation against such pressure, Albania was no longer able to rely on support from the other side of the Adriatic as it had under King Zog. It was pointless to expect protection from England, America or Russia to counteract the Greater Serbian bloc. Russia was excluded from the start as a Slavic power because its policies in the Balkans were always pan-Slavic in nature. Despite all its promises and its support for the Albanian armed bands with gold and weapons, England had made it clear enough that it regarded active policies in the Balkans as unthinkable without a Greater Serbian state. For America, Albania was at the most an interesting operetta country in distant old Europe whose oil deposits were too limited to justify any active intervention in the country.

The last foreign country with any potential interest, and one that had had intimate relations with Albania over the centuries, was Turkey, but it was weak and too busy trying not to get caught up in the turmoil of war. As such, no more than expressions of platonic affection could be expected of it.

Lack of Consistency of German Policies in Albania

In terms of practical efficiency, German policies in Albania suffered most of all from the fact that they were not consistent, that responsibilities were often unclear and that a common course was not always achieved to deal satisfactorily with acute problems.

The Albanians were sensitive enough to recognise this lack of consistency in German policy and, in true Balkan fashion and not unsuccessfully, they endeavoured to take advantage of the conflicts within the German side. If one German authority did not fulfil their wishes, they would turn to another one. They also showed surprising talent in playing one German official or institution off against another, and often managed to create hostility between them. It is obvious that German influence declined as a result. With time, the DGA lost control of the game.

Events, seen on the surface, seemed calm until the beginning of August 1944, although the clefts and tension in the regime were increasingly obvious to anyone in the know.

Antipartisan unit in Albania,

autumn 1943.Events Since the Autumn of 1944

The initial catalyst in the decline, that rapidly transformed itself into a destructive avalanche, was the break with Turkey. The position of Turkey, with which Albania had close ties, was a barometer for its reactions to the war. When the Turks finally and definitively changed sides, it served to motivate all the other undecided figures and movements to break with Germany.

New impetus to the collapse was given by the capitulation of Bulgaria that brought the war right to Albania’s borders. Nationalist wishes and claims for border changes arose that were of course anti-Bolshevistic in nature, but it soon became apparent that Germany was militarily unable to deal with the situation in and around Bulgaria and this brought about a clear re-orientation of affiliation towards the Communists. The armed bands in the border regions increased in strength with the support of strong and efficient Bulgarian guerrillas no longer under the control of the army.

A further weakening of Germany’s position was caused by the transfer of many good fighting units to the Bulgarian-Russian front such that by September it was increasingly evident that the situation was deteriorating even more rapidly towards a general uprising and the definitive loss of Albania.

Finally, with the Allied invasion from the West, the desertion of Germany’s allies and the Russian advance in the East, the general military decline of Germany provided the best reason of all for anti-German formations to become active. This decline could not be compensated for in the long term by the new V-weapons, and gave impetus to the armed bands throughout Albania. A major offensive in southern Albania managed to break up the so-called Soviet Republic in the region of Gjirokastra and Erseka, but the solid fighting units of Mehmet Shehu were not destroyed. They simply withdrew to central and northern Albania. This suddenly jeopardised a region that had earlier been relatively calm and led to the closure or repeated interruption of important roads.

In view of the importance of the road network in Albania, these closures to traffic meant in essence that the armed bands now held sway throughout the country, with the exception of the towns still occupied by German troops.

Impotence of the Albanian Government

The influence of the official Albanian Government declined in favour of these strong irregular troops. From September onwards, the Government had virtually no influence whatsoever.

Failure of the Albanian Government Administration

Just as lamed as the Government was the whole administration. Even in peacetime, officials were corrupt, lazy and incompetent through and through. With the progressive collapse of the regime, such inherent characteristics only got worse. In September, the situation was such that only about 10% of government officials actually went to work. All attempts by the Administration Group to intervene here failed because of the fiction of an “independent, free Albania” to which Neubacher adhered right to the bitter end.

The only laudable exceptions to this general lethargy were a few provincial officials. They countered the red and white terror, but were dependent upon energetic support from the local German commanders, who fulfilled their responsibilities. Foremost among these provincial officials are Vizdan Resalia, the prefect of Vlora; Mahmut Cela, the prefect of Durrës; and Hasan Isufi, police chief in Shkodra. By ruthless intervention, they created relative order in their regions of responsibility and proved that in times of unrest, the semi-savage Albanians could actually only be governed by fear and intimidation and that, at least at this point in time, the policy of sitting around and doing nothing was wrong.

Albanian cabinet under

Mehdi Frashëri, October 1943.Collapse of the Albanian Executive Authorities

The country’s executive authorities were an even greater failure than the officials of the government administration. By the end of July, activities to consolidate the Albanian gendarmerie had to be suspended as the project had become untenable. All of the local units failed or abandoned their posts and simply went home. In many cases they actually went over to the other side, to the armed bands, and took their German weapons with them. It was more than evident that the policy pursued in Albania of arming instead of disarming the population had turned into a disaster in view. During the withdrawal, just as many German weapons were being fired by the other side as from the German side.

Evacuation of Southern Albania

The situation got worse and worse from about September onwards. Since southern Albania was no longer needed for the evacuation of German troops from Greece, it was progressively abandoned. By 17 October, German troops had withdrawn from up to a line between Kavaja and Berat.

Situation in the Capital

Though despite the fighting it was still possible to extract our troops here according to plan, tension exploded in Tirana. From the end of August onwards, all the armed bands seemed to be magnetically attracted to the capital. Easy success seemed to be waiting for them, all the more so because the disorganisation of the Albanian government authorities was particularly obvious here. All leading posts in the Albanian administration needed to be filled urgently. The prefect, Muleti, a thoroughly unreliable figure, had abandoned his post and fled to Germany. His deputy, Pekmezi, was rejected by those in the know as a communist. He defected to the armed bands during the siege of Tirana. After Fortuzzi’s flight to enemy-occupied Italy, the position of mayor of Tirana was given to someone who was completely incompetent. In order to maintain a semblance of public order, the Administration Group proposed fusing the positions of prefect and mayor, and handing the new post over to the prefect of Vlora who, by the way, had his own fighting forces of about 500 men that had been quite successful in combating Communist terror in Vlora. Were Resilia for any reason not to be available, the prefect of Durrës, Mahmut Cela, was proposed as a second choice. For reasons we did not fathom, Gstöttenbauer treated these suggestions in a dilatory manner and succeeded more or less in sabotaging them. Instead, Gstöttenbauer and Gruppenführer Fitzthum decided on a three-person defence committee for Tirana, General von Myrdacz, Pekmezi and the director of the Albanian security forces. Unfortunately, this committee was unable to accomplish anything when Tirana was surrounded and besieged because the seventy-year-old General von Myrdacz was very soon captured by the armed bands, the head of the security forces had fled to Shkodra by this time, and Pekmezi defected to the bands after he had sniffed about and learned enough about German positions, troop strengths and tactics.

On 27 October, before the uprising in Tirana, the corps staff left the town as part of the general evacuation and moved to Shkodra.

Forced Resignation of the Government and Regency Council

The day before, the chief of staff of the 21st Mountain Army Corps, upon the request of the representative of the Special Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, forced the Government of Biçaku [Biçakçiu] and the Regency Council to tender their resignations. This was done without the knowledge of the head of the Administration division. The Administration Group bears no responsibility for this political act that was in blatant contradiction to the previous policy of strictly respecting the neutrality of Albania. In its implementation from the point of view of international law, this policy was questionable to say the least, and as a practical consequence it only accelerated the chaos in Tirana and central Albania. With regard to formalities, this solemn political act, which constituted a definitive turnaround in German policy on Albania, was carried out so carelessly that the official Albanian-language deed of resignation of the Regency Council was not even translated into German by an interpreter. All we got was a cursory German translation made by Frasheri junior. During the evacuation, Vehbi Frasheri then told us that the original Albanian version of the resignation, in the passage in question, was unclear and completely open to interpretation. When he translated it, he chose a version that gave the German authorities the impression that the Regency Council had indeed fully submitted to all German demands. In fact, the original text left the Regency Council with the possibility of returning to government in the future because it was unclear in this Albanian version whether or not it had actually resigned.

In practical terms, the fall of the Government on 27 October meant the end of all peacetime administrative activity in Old Albania. The following period can only be described as a state of war in the regions south of Shkodra. The military situation for this period has been set forth in another special report.

Fighting in Tirana

On 30-31 October 1944, a general assault on Tirana was carried out by the armed bands. Most of the capital city was destroyed in twenty days of street combat. We are of the view that this dramatic worsening of the situation would not have been necessary. It could have been avoided if the authorities had not, for reasons of formality, acceded passively and indeed demanded the dissolution of the Albanian Government. The Administration Group repeatedly pointed out that countries without leadership and organisation by nature always led to anarchy.

The further evacuation from Albania took place without any major fighting. The last German troops left the country on 4 December 1944.

Administrative Activities during the Evacuation

Administrative activities in this period were of course primarily determined by the fighting that was going on. Other standards would be needed to evaluate the methods and success of our work in this period compared to peacetime, work that was continued with the express wish of the troops.

The Administration had no more reason now to adhere to the policy of Albanian neutrality. It was able and forced to intervene with its own resources where this was essential to German interests. Its objective was now no longer to regulate the country in its own interests, but only to keep the population quiet so that German blood would not unnecessarily be spilt during the evacuation.

What the Administration was able to do was simply to ensure that day-to-day business be continued, i.e. dealing with compensation claims, assisting essential businesses and utilities and, in particular, in exerting influence on non-communist Albanians of influence so that they would keep the population quiet for as long as possible.

To what extent the continuation of our administrative activities actually helped in getting German troops out of the Shkodra region without any major fighting cannot yet be said. The troops, however, showed that they appreciated the work of the Administration because they specifically requested that an administration official remain behind until the last troops had left the country.

Grave of Mehdi Frashëri in Rome

(Photo: Robert Elsie, March 2011).

Flight of the Non-Communist Politicians

Almost all non-Communist Albanian politicians left the country with German troops, or had done so beforehand. Those individuals who were not of interest to the German authorities were assisted in Bar in getting to Corfu or Italy by boat at their own risk. Those who had been in exposed positions in German service and those figures for whom the German authorities wanted to make sure they did not fall into the hands of the enemy, in particular Frasheri father and son, were evacuated with the troops in a transport convoy arranged by Mellin. In Sarajevo they were then taken over by the SS and transported back to the Reich.

The true nature of the bands in Albania can be seen in this almost universal departure [of political leaders]. The course of events left one with the impression that the future of Albania would now be determined primarily by England. The Albanian armed bands were now supported exclusively by Anglo-American staffs, and the deployment of Badoglio troops, which we found out about, only increased the sphere of English influence.

Russian Influence in Albania

On the other hand, all Albanian politicians did agree that, Russian-Bolshevist influence was much stronger in the underground. With a very few exceptions, they all continued to have good contacts with the Western powers. Yet, had they really had confidence in English influence, they would never have left the country. They were sure that Albania would come under the full sway of Russia. The Albanians are very sensitive to the subtleties and realities of domestic and foreign policy, and the universal flight [of the political leaders] throws much light on Russia’s advance towards the Adriatic.

Communist partisans in Përmet,

May 1944.Probable Development of the Situation in Albania

It is very difficult to make a guess as to the political future of Albania. The economic difficulties that can be expected, the innate anti-authoritarian attitude of the Albanians and the inability of the current rulers to fulfil even a small portion of the promises they have made, will no doubt drive a good proportion of the Albanians into the mountains by the early spring and, thus, problems with armed bands will begin anew in the opposite direction.

In conclusion, the German occupation of Albania seems to offer proof that the Albanian people are not by any means mature enough to govern themselves. Only if a strong and just foreign power without ulterior motives comes and takes over the country for at least one generation and gradually educates its inhabitants towards independence, will Albania – beautiful and, to a certain extent, promising as it is – be saved from the eternal internal conflicts that will end by destroying the nation entirely.

III. Duties of the Administration

In the neutral state of Albania, the duties of the German Administration were of course different from what they were in formally occupied countries since the ‘work’ was limited to spheres that were of essential importance to the German Wehrmacht. In addition to this, in theory at least, the Albanian administration was supposed to be functioning. However, in view of the incompetence of this national administration, the German authorities were not always able to abide by the restriction.

(a) Internal Administration

Consolidation of the Albanian Administration

The internal administration of the neutral state of Albania should have been the exclusive prerequisite of the national authorities.

The structure of the Albanian administration was modern. It extended from the Ministry of the Interior to the prefectures (provincial authorities) and the municipal and village authorities. Similarly organized from top to bottom were the executive, the gendarmerie and the police.

In addition to this western-style hierarchy, there existed among the rural population the office of the village elder, some of whom were elected while others inherited their titles. Among the semi-nomadic mountain inhabitants devoted in good part to herding, there was the chief and superior chief (bajraktar and superior bajraktar). The German authorities unfortunately did not take due account of the influence of this solid institution, just as they tended to ascribe too much importance to the central government.

Lack of Influence of the Albanian Central Government

The influence of the Government in internal administration did not extend any farther than the region under German control, i.e. barely beyond the municipal limits of the towns. Another reason for this was that the western-style administration had no solid roots in the population and that most of the officials were corrupt and, quite often, politically unreliable. The cautious influence exerted by the German authorities, who were misled and blinded by the modern buildings in Tirana, was therefore limited to requests made of the ministries, and had little success. All sorts of glowing promises were made, but little was actually done in practice.

Significance of the Provincial Authorities

More positive results were achieved with the prefects since they had more direct contact with the population. The Local Commands were the only German administrative authorities in the provinces and were located at the seats of the prefectures. As a result, German institutions here could exercise discreet but more effective influence upon the Albanian administration. The Foreign Office, however, showed incomprehensible reticence and decided, perhaps more than necessary under the given conditions, to work directly with the Albanians.

In view of the significance of the prefects in maintaining order and security in the country, priority should have been given to exerting influence in filling these key positions. Unfortunately, here too, there was too much reticence due to excessive respect for the country’s neutrality, which was not always in accord with German interests. Practice showed that the importance of the provincial authorities was not simply theoretical. In those areas run by energetic prefects who were willing to put up active resistance to the Communists, there was relative peace and quiet.

Proposals of the Administration Group for Change

In September 1944, in clear recognition of the situation, the Administration Group repeatedly and urgently suggested to Oberführer Gstöttenbauer, who at that time had all the strings in his hands, that he intervene more actively in the internal administration of the country because any further passivity would be against our interests. It was proposed that power be shifted from the incompetent central government via the Local Commands to the prefectures and that all conceivable direct pressure be exerted upon the village elders and chiefs.

This experiment in creating a camouflaged German administration without proclaiming a state of emergency seemed under the given conditions to be the only possible way of exerting German influence, via the Albanian authorities, on the events that were taking place. Oberführer Gstöttenbauer, however, did not approve of the proposal and, despite preparatory work carried out by the Administration Group, virtually nothing changed. The real reason for Gstöttenbauer’s refusal was no doubt that they still wished to maintain the fiction of a neutral, independent Albania.

Preparations for Imposing a State of Emergency

In some aspects, the Administration Group did have to intervene theoretically in the internal Albanian administration, in particular at the beginning of summer when the Commanding General of the 21st Mountain Army Corps ordered administrative steps to be taken to prepare for the imposition of a state of emergency. Orders and notifications were readied and distributed. However, the proposed measure was never carried out since the general uprising against the occupation took place so swiftly that declaring a state of emergency would have been quite superfluous.

Evacuation of the Coastal Region in the Spring of 1944

In one instance, the Administration was, however, forced to intervene in the country’s internal affairs. That was in the early spring of 1944 when, on orders from the Commanding General, it was given the task of evacuating the coastal region. The corps held the view that our sea defences could only be kept up if the whole coastline were to be evacuated of its population. The evacuation, implemented in coordination with Ministers Deva and Aga, affected three zones. A small area right around Vlora, another area around Durrës that had already been evacuated, and an area at the mouth of the Bojana [Buna] River near Shkodra were evacuated swiftly and in their entirety. A second zone comprising all the territory between these initial areas to a depth of about fifteen kilometres was to be evacuated more gradually. Subject to certain precautionary measures, agricultural activity was still to be permitted here, where possible. The third zone was only to be evacuated in the case of an enemy landing.

It was agreed with the Albanian ministries that the German and Albanian authorities would take joint responsibility for the evacuation, whereas accommodating the evacuees would be the sole responsibility of the domestic administration.

The Albanian administration showed itself to be completely incompetent in the practical implementation of this undertaking. In the end, the evacuation was only carried out successfully because the German authorities took control of everything themselves. With the Albanians giving proof of their utter incompetence, caring for and sheltering the evacuees proved to be an unsolvable problem, even when our Administration intervened to provide assistance. Since no Albanian would help, the assistance we provided had no effect whatsoever.

The evacuation had a substantial repercussion on the country since it was carried out in the main agricultural regions of Old Albania and, despite all the assistance the troops could provide, there was virtually no sowing and harvesting that year. In addition, the tens of thousands of people who had to be evacuated from Durrës and the coastal region caused great unrest in the country since the Albanian Government proved to be incompetent at providing any assistance or direction. Since no assistance was forthcoming, most of those who were evacuated probably took to the hills and joined the armed bands. We are not in a position to judge to what extent the evacuation, in view of the consequences, was actually necessary in the final analysis, in particular since the anticipated landing on the coast never materialized.

Rail line on Lake Ohrid (Photo: Centre

for Albanian Studies, London).

(b) Transportation

Old Albania, a Country with No Railway

Transportation issues in Albania are determined mainly by the fact that the country faces the sea. In view of its long coastline and sufficient harbours, it would normally rely primarily on maritime transportation. This and the fact that the country is dependent on Italy and has thus turned its back on the rest of the Balkans explain why railways play no great role in Albania. Aside from a secondary narrow-gauge rail line from Struga via Tetovo to Skopje that was only of importance for the chrome ore mine in Pogradec, Albania had no railways at all. The rail line planned and initiated by the Italians to link Tirana, Durrës, Elbasan and Struga, with a future link to the north-south line through the Balkans was not constructed any further because its importance and thus the ensuing costs were in no relation to the beneficial effects it might have had.

Only in Kosovo was there a rail line, a section of the railway linking Skopje, Kosovska Mitrovica and Belgrade that ran through the region. Because it was the only rail connection, this line was important for supplies and for any potential evacuation of our troops, but it was of no significance for inner-Albanian traffic.

Because there was no more maritime transportation and no river transportation to speak of, aside from traffic on a short section of Bojana River between Lake Shkodra and the Adriatic, all domestic traffic in Albania was dependent upon the road network and upon motor vehicles. For this reason, the transportation problem was the determining factor for all economic issues. This was especially true for oil and chrome extraction.

Importance of the Road Network and Truck Transportation

Interurban transportation relied entirely on the roads built by the Italians, that were all still in excellent shape. North-south traffic made use of the coastal road from Himara to Shkodra via Vlora and Durrës and of another road in the eastern part of the country from Florina via Korça and Struga to Kosovo. East-west traffic used either the southern route from Bitola to Struga, Elbasan and Tirana or the northern route from Uroševac [Ferizaj] via Prizren to Shkodra.

Much transportation in the interior was conducted on mountain trails, just as it was in ancient times. Thus, in isolated regions, in this country where the Middle Ages and modern times intersect in all spheres of life, mules and donkeys were still just as important for moving goods as were trucks, Koms and private vehicles.

This rather curious transportation situation, the marshlands along the coast and the impenetrable mountains in the interior meant that controlling the major roadways and keeping them open became the major problem faced by the whole occupation. The fight for control of the roads is described above.

From an administrative perspective, the transportation problem can be divided into road maintenance issues and management of vehicle traffic.

Road Maintenance

After much experimentation, road maintenance was organised as follows: responsibility for strategically important roads was given to the 21st Mountain Army Corps and responsibility for all other roads was given to the DGA and thus to the Administration Group. For the technical aspects of road maintenance, the Corps had the OT [Organisation Todt] units in Albania at its disposal, whereas the DGA had to rely on the local road maintenance authorities. It was an endless and unavailing problem for the DGA since the latter authorities were under the direction of and were financed by the Albanian ministry. Weeks of negotiations were needed with the Albanian side to get even minor road repairs done. Sometimes there was no equipment available, at other times there was no personnel, and the requisite funds were always lacking. Suggestions that the locals might be conscripted to carry out minor road repairs came to nothing because of the Albanian reluctance to do any work, in particular anything in the common good.

If anything, despite these impediments, was accomplished at all, it was due to the fact that the Italian road construction companies in Albania did excellent work and that the Albanian specialist at the ministry, Hifza Korça, was one of the rare Albanians who was not only a good friend of the Germans and thoroughly versed in his speciality, but also had energy to get things done. Working with him was one of the few pleasant experiences the Administration had in this field in Albania.

Departure of the OT [Organisation Todt] in August 1944

The Administration was given responsibility for maintaining the major thoroughfares, too, when the OT suddenly left the country in August 1944. The increased work load was, however, manageable since in the autumn, with the coming evacuation and the general chaos in the country, only really essential repairs, such as bridge and road section replacements, were carried out. By this time, the situation had become much more critical and these repairs could no longer be carried out with the help of civilian labour and private companies. Only German pioneers were left to tend to the evacuation routes.

In addition, the OT left the Administration Group with many problems when it departed without a proper handover and without having paid the large debts it had incurred with private companies. The creditors all rushed to the Administration to be paid and the latter was faced with claims in the millions, without having any documents or money to process them. Some of the most urgent cases were paid out by the Wehrmacht inspector as far as he could. The other cases were at least registered, as far as possible. It is likely that substantial claims, hard to verify, will later be made against the Reich for the debts incurred by the OT.

Bridges Blown Up during the Evacuation

During their evacuation, the troops were forced to blow up most of the bridges in order to prevent the partisans from pursuing our forces. The future development of the country will no doubt be affected by this necessity of war, provoked by Albanian guerrillas. The Albanians will never succeed on their own in restoring these constructions, some of which were very complex. It is conceivable, given the decisive importance of roads and road traffic, that the country will be thrown back several decades in its development.

Rendering the Harbours Unusable

Maritime traffic has also suffered greatly from the destruction of the harbours brought about in connection with the war. The blowing up of the breakwater in Durrës that the Italians had spent years extending for kilometres into the sea, thus making Durrës a modern port facility with substantial capacity, can only be made good if an international agreement can be reached after the war, in which Germany pledges to rebuild it.

Management of Road Traffic

The management of road traffic was a major problem from the very start. The German authorities had two reasons for intervening:

1. with the lack of fuel reserves, it was not possible to allow everyone in Albania to use their private vehicles whenever and however they wished;

2. in view of the problems in the transportation sector and in order to ensure provisions for the country and for the troops, it was necessary to make use of freight capacity to the full and to avoid empty runs.

The attempt made by the Administration in 1943 to limit vehicle traffic by means of restrictions on vehicle registration as in Germany failed because the Albanian gendarmerie was responsible for the approval of applications and the Germans were simply to register the vehicles and provide them with a stamp on the so-called AI papers, without verifying anything. Making the Albanian gendarmerie responsible for verifications made the entire procedure a waste of time from the start because they regarded the whole thing as a way of making money for themselves. Anyone who paid the requisite bakshish got the permission he required.

The Administration continued to collaborate in this farce simply in order to acquire card documents that could be utilised for a subsequent stricter control of vehicles.

On top of this, from December 1943, the Commissioner for Economy and Finance was given exclusive responsibility for managing road traffic and made a great point of stressing his rights. The Administration Group repeatedly suggested that the situation be altered because it was impossible to keep domestic vehicle traffic on the roads without major restrictions in view of the increasingly drastic shortfalls in fuel supplies.

German troops in Albania

in September 1943

(Photo: Bundesarchiv).Proposals of the Administration to Restrict Vehicle Traffic

Proposals to ration fuel were rejected by the Commissioner for Economy and Finance due to legal obligations towards the Albanian Government. He claimed that only essential official traffic was being allowed on the roads under this quota. He also rejected the claim of the Administration which stated that it had certain knowledge that the Government quotas were being subverted by Albanian officials and sold on the black market. The many attempts of the Administration Group to reduced quotas for gasoline and diesel because of the war were only taken seriously in the autumn of 1944 when the 21st Mountain Army Corps intervened and the Commissioner for Economy and Finance left Tirana. Distribution of fuel was then given to the Administration to deal with. The Administration was able to prove the validity of its position in practice by rigorously cutting back on fuel quotas, without, however, affecting the essential needs of the civilian sector.

Carpooling

Since no improvement in the fuel situation had been attained or was to be expected by the spring of 1944, the Administration prepared a detailed plan to rationalise freight capacity under German supervision by carpooling and through the joint usage of civilian and military cargo space. It was only after tedious negotiations with Richardt that the basics of this proposal were implemented, although Richardt insisted on the principle that there should be no German military interference in Albanian internal affairs. When the Corps put pressure on him, he authorised a transport officer to be hired in his staff, thus creating a central German authority to put some sense of order into the chaotic situation. The organisation, however, suffered from the fact that the branch offices were run by Albanians. Things only functioned outside of Tirana where the German authorities ignored Richardt’s instructions and supervised the Albanian transport officials themselves. In the end, this regulation brought about a substantial improvement in the transport situation and facilitated supplies not only for the Albanian population, but also for manufacturing companies needed by the army and for the troops themselves. Had this wartime regulation been implemented earlier, it would have been of greater service to the German occupation than it actual was, being that the days of German rule were now drawing to a close.

Confiscation of Vehicles during the Evacuation

The Administration Group had to deal with other traffic issues in the autumn when it was ordered to prepare for the confiscation of trucks either for use by the troops or for destruction if they were not needed. The files assembled by the Administration Group proved to be of great use in this connection. The confiscation schedules set forth were only partially adhered to because some units acted of their own accord. As such, truck owners got wind of the action in advance and had time to hide their vehicles or to immobilise them by removing parts.

(c) Public Health

Combating Malaria

In public health matters, the German occupation authorities only had to deal with combating the spread of malaria. Albania is one of the worst regions in Europe for malaria. During the [First] World War, up to 100% of Austro-Hungarian troops were infected because no precautions were taken, and in the recent fighting, up to 50-60% of all Italian troops were infected. In awareness of this, energetic steps were taken from the start to combat the disease. The Germans took over the local facilities for exterminating mosquitoes and the pumping station in the lagoon of Durrës, and great attention was paid to mechanical means for combating the fever. All troop accommodation was equipped with mosquito mesh and soldiers were all given mosquito nets. Strict military measures were also taken to ensure that all the soldiers took their Atebrin daily. In addition, press and radio informed the troops repeatedly of the danger of malaria and of the means to combat it.

These measures proved to be of greater success than expected. Although 1944 was a real mosquito year, few soldiers were affected. Only about 5% of the troops caught the disease. German methods and energy proved here that the epidemic that affected the whole population of Albania did not have to be an inevitable fate.

Venereal Diseases

Combating venereal diseases in Albania was somewhat easier since - for reasons of religion - the female population was reluctant to engage in sexual activity. As such, contact was limited primarily to the brothels. A mass infection of the troops was avoided by setting up Wehrmacht brothels under permanent German health supervision and by strictly policing the other illegal brothels.

Papadaci Fever

German doctors were at a loss only with Papadaci fever. However, the army was not substantially affected in its fighting strength because, although this fever acts initially much like a severe case of flu, its symptoms clear up quickly and have no lasting effect. The troops were not affected by any other dangerous epidemics in Albania. It was only during the evacuation that some individual cases of typhoid fever occurred.

Albania in the Second World War

(Photo: Janusz Piekalkiewicz).(d) Culture

German-Albanian Cultural Relations

The promotion of cultural relations between Germany and Albania was a particularly enticing field because of the close ties the two countries had enjoyed from before the Italian period. A good number of educated people in Albania had studied at schools and universities in Greater Germany, in particular in Vienna, Graz and Innsbruck. The educated Albanians with German upbringing retained a strong attachment to German culture and were reliable and supportive of our relations. Taking advantage of this fact, the German Mission endeavoured to pave the way for the future by promoting various opportunities for young Albanians to study in Germany. In the summer, an initial contingent of 100 students left as a group to study in the Reich, and further numbers followed later. The Administration Group was able to assist them with technical arrangements for their travel and by maintaining postal services for them outside Tirana through the local commands.

Protection of Archaeological Sites

In co-operation with the cultural attaché of the German Mission, the Administration provided information to the troops to ensure that objects unearthed at archaeological sites, for instance during military fortification work, be handled properly and kept in the country. However, as these peaceful measures were introduced in the summer, nothing much was achieved because of the rising chaos.

Activities of the Propaganda Division

The skilful and successful work of the Propaganda Division was focused more on information and propaganda activities. It supplied the few cinemas in the country with German films and provided material for an evening of entertainment for Germans and Albanians in Tirana every two weeks. The level of performances did not rise above that of simple-hearted entertainment but they were well attended by the Albanians. The Propaganda Division also skilfully controlled and influenced radio broadcasting and the press, and was able to ensure that the few news agencies remained under German control until the very end.

The Administration Group worked closely with the Propaganda Division and in a number of cases it was able to provide substantial material and non-material support. It exchanged ideas on an almost daily basis with the head of the Division and provided him with its wealth of experience about Albanian public opinion and how to influence it. In addition, it dealt with the administrative and legal aspects of opening cinemas, etc.

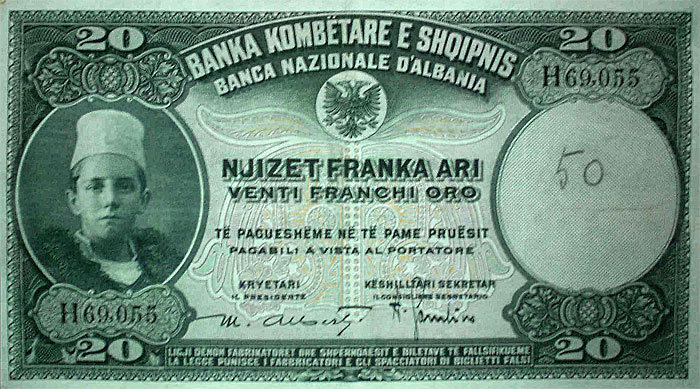

(e) Finances

Funding of the Wehrmacht

The financial situation of the Albanian state was only of concern to the German authorities with regard to funding the Wehrmacht. In recognition of Albanian independence, a basic agreement was reached between Germany and Albania that all contributions would be paid by the Reich. Since Germany did not have cash available in Albanian currency, requisite funds were dependent upon the situation of the Albanian treasury. In many regions taxes and revenues were not received at all, and in others, only with substantial delay. As such, there was always a lack of funds in the state treasury. For this reason, an attempt was made to bridge the gap by printing new money. The result was, however, unsatisfactory because the original printing block for Albanian francs was in Rome and thus not accessible.

Financing the Wehrmacht involved importing gold which had to be sold on the open market since the Albanian state bank did not have enough cash reserves, and importing scarce commodities such as sugar, drugs, chemicals and machine parts.

Neither action sufficed to provide full compensation for Albanian claims. As such, many Albanian claims, in particular in the chrome mining sector, were left for after the war.

Funding the Wehrmacht was one of the major duties of the German Foreign Ministry and, later, of the representative of the Special Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Despite all the impediments, they managed to solve this thorny issue satisfactorily right to the end.

Payment of Soldiers’ Salaries

Problems arose, however, in the payment of soldiers’ salaries. Salaries were paid out right to the end on the basis of a calculation made in the autumn of 1943. As purchasing power continually declined, the value of their salaries diminished. In addition, all the other Germans working in Albania (police, OT, customs officials, not to mention civilians) were receiving far higher wages. All this had a very negative impact on troop morale. The military courts were constantly filled with cases brought for the illicit sale of fuel, tires and military equipment. Had a more just solution to the salary issue been found, even in the form of a partial credit voucher for use back in Germany, the courts would not have had to hear the eternal moaning of convicted soldiers who complained that the state had robbed them of their wages and they were simply helping themselves to what they were entitled to.

Albanian Compensation Claims

The Administration Group was peripherally involved in finance problems since, together with commissariat-officials, it had to process Albanian compensation claims for damages caused by the Wehrmacht. It always endeavoured to reduce these constantly inflated and often unjust claims made by Albanians to a normal level in order to avoid the inappropriate use of German funds.

German-Albanian Compensation Office

In the summer, the Commissioner for Economy and Finance transferred the often very complicated financial duties involved in importing goods from Germany to a new German-Albanian Compensation Office, DAB [Deutsch-albanisches Ausgleichsbüro]. It was the chore of this institution to carry out the thorny negotiations with the Albanian side on price fluctuations. Thanks to the solid work it did, a satisfactory level of goods was initially ordered from Germany. Because of increasing transportation difficulties, however, the goods arrived with much delay and, as a result and due to the general situation in the early autumn, the interested parties lost confidence in the exchange, and the activities of the DAB came to a halt. The DAB had no branch offices outside of Tirana. Since most of the orders came from there, the Administration proved to be of great assistance in requesting the presence of the local commands at negotiations there. The result was close and good co-operation with the DAB.

(f) Justice

Activities of Albanian Courts against the Communists

In general, the German Administration had no reason to interfere with the justice system of neutral Albania. The only thing it was interested in was evidence obtained by Albanian courts when they took over responsibility for prosecuting Communists who were not caught red-handed in attacks on German soldiers or on German military property. However, since fighting the Reds soon became the exclusive job of German troops and security organs, due to the inefficiency of the local judicial authorities, the Albanian judicial system became irrelevant.

Cleft between the Law and Economic Development

With reference to Albanian legislation and jurisprudence, it must be said that, here too, as in virtually all spheres of life in the country, there was a huge cleft between progress and the primitive lifestyle still prevalent there. Having adopted the latest foreign laws, Albania had the most modern legislation and jurisprudence one could imagine. This contrasted sharply with the whole social and economic structure of the country, at least in the countryside, that was centuries behind the rest of Europe. Justice is always a reflection of the conditions existing in a country and any accelerated change brings about great upheaval to government and social life. This was one of the main reasons for the instability of the state.

(g) Labour Service

Impossibility of introducing an Albanian Labour Service

As workers were often lacking to carry out essential services such as road construction and building air-raid shelters for the civilian population, the Administration looked for ways and means of introducing an Albanian Labour Service. The issue was not pursued, however, since the responsible Minister Deva declared from the start that such an undertaking was impossible, and the Administration realised that the State would never dispose of sufficient power and authority to do anything useful.

(h) Labour Service in the Reich

Possibilities for Recruiting Workers

It would actually have been easy to hire a substantial number of workers for labour in the Reich since, with the rise of insecurity within the country, more and more people were applying to the Administration, hoping to escape the chaos. Despite the repeated suggestions of the Administration Group, it was not possible to set up such an organisation for Old Albania.

It was only in Kosovo that a representative of the Commissioner for Labour Service was active. However, as he was unable to work effectively with the other German services, the Administration was forced to intervene on several occasions to smooth over relations. No data are available as to the number of persons hired for work in the Reich.

(i) Foreigners

In Albania there were two main groups of foreigners:

1. the Serbs in Kosovo, and

2. the Italians, present throughout the country, but primarily in Tirana.

Serbs in Kosovo

The Serbs in Kosovo were the economically most progressive element of the population in northern Albania. They possessed the medium-sized manufacturing businesses there: watermills, tanner shops, sawmills and businesses providing supplies. Serb farmers, of whom there were substantial numbers, were quite progressive compared to their primitive Albanian counterparts. It was thanks primarily to their economic input that the Kosovo region was able to continue feeding Old Albania with its surplus production.

The general aversion of the Albanians for the economically superior Serbs, who first immigrated into the country in 1919, was a constant source of trouble. One of the most difficult and important chores of the Administration in Kosovo was to nip all potential conflicts in the bud. The German Wehrmacht often had to intervene with its full authority because the Albanians were moved to drive the Serbs out of the country not only by their aversion of them, but also simply by greed, i.e. in order to get possession of their property.

Mosque in Kavaja (Photo:

Richard Busch-Zantner, 1939).Italians in Albania

The problem with the Italians was similar but more complicated. In economic terms, the Italians were needed absolutely in Albania unless the German authorities were willing to second skilled workers from the Reich to replace them.

All of the major industrial and manufacturing companies in Old Albania were either Italian-owned or Italian-run. In addition, almost all of the specialists in the country — auto mechanics, electricians, welders, lathe operators, etc. were Italian, as were the good road construction workers. The German Wehrmacht was therefore exceptionally interested in maintaining these skilled labourers, many of whom were highly qualified.