| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

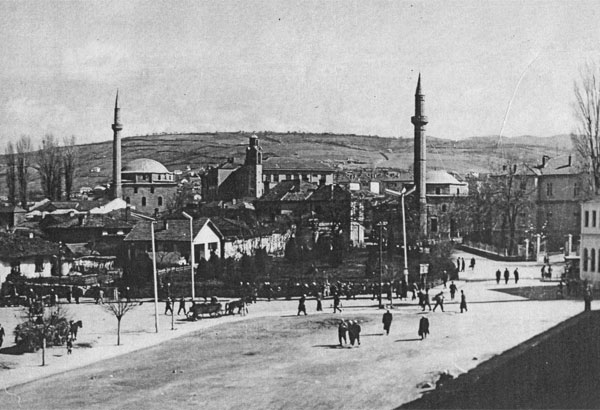

Photo of old Prishtina.

1945

Ralph Skrine Stevenson:

Kosova in the spring of 1945The Second World War ended in Europe on 7 May 1945. German forces had withdrawn from Kosova on 19 November 1944 on their retreat northwards, leaving the region in a state of confusion and uncertainty. British career diplomat, Ralph Skrine Stevenson, who had served in Spain during the Spanish Civil War and was later to become British Ambassador to Egypt, was in Yugoslavia after the German withdrawal and sent the following report to the Foreign Office, describing the turbulent state of events in Kosova and western Macedonia in the spring of 1945.

Belgrade, 21th April, 1945

1. I have the honour to report that there have recently been a number of indications that in the last few months there has been serious unrest amongst the Albanian population of the Kosovo and Metohija, and the north-western corner of Macedonia.

2. The areas in question have throughout the war been in the main hostile to the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation and it appears that up to the present the partisan movement has found little sympathy or understanding there. This is due to a number of factors, the chief of which was the repression of the Albanian minority by the Yugoslav Government between 1920 and the present war. This encouraged Albanian irredentist feeling in the Kosovo which was fostered by the League of Prizren, subsequently called the Kosovo Committee, formed in 1920 by Albanian landowners and chieftains to work against Serbian domination. When, therefore, the Yugoslav State collapsed and Albanian appetites were satisfied by the inclusion to Albania all the Kosovo, Metohija and north-west Macedonia, the Italians found in the Kossovars ready collaborators. Kossovars were recruited in 1941 into an armed guard, formed by General Prenk Prevezi, which was responsible for the protection of the new frontiers and for policing within them. The Kossovars took the opportunity for revenge on the Serbian colonists, and many of the latter were forced to flee for protection over the frontiers to Serbia and Montenegro where they joined either the Partisans or the Cetniks. The Kosovo forces in their occasional raids over the Serbian frontier behaved with the utmost brutality towards the Serbs who opposed them. With the collapse of the Italians, whose popularity waned with the length of their occupation, the Germans exploited even more successfully the irredentist elements amongst the Kossovars. There was talk of according autonomy to the Kosovo and this was partially realised when the Kosovo was given a semi-autonomous constituent assembly at Prizren in March 1944. The Germans succeeded in expanding the existing units formed in the Kosovo into the S.S. Skanderberg Division of some 7,000 men, officered by Germans. This was formed in March 1944. At the same time, a conference of chiefs at Maqellare and Rogovo decided to set up a military committee for Kosovo and Metohija and undertook recruiting drives throughout the territory. These drives had considerable success. Frontier guards were strengthened, Albanian police units were formed and used to garrison Serbia, and the Kossovars were even despatched to garrison France and the Low Countries.

3. In the face of this strong opposition, the partisan movement in the Kosovo never reached considerable proportions. From 1941 efforts had been made to enlist some support amongst the Albanians and in that year, two delegates from Tito, Ali Dusanovic and Miladin Popovic, are believed to have attended a conference of the Albanian Communist party. They were arrested in Albania in 1942 but escaped with the help of Albanian Communists, and apparently continued to maintain contact between the Yugoslav partisans and the Albanian Communist party and to try to build up the partisan movement in the Kosovo and Metohija. Towards the end of 1943, the first was heard of Kosmet, the staff of the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation for the Kosovo and Metohija. This was responsible directly to Tito and consisted half of Serbs and half of Albanians, amongst whom were Mehmet Hoxha and Fadil Hoxha. Kosmet was forced to confine itself to political activity, mainly trying to abate anti-Serb feeling among the Kossovars. Some attempt was made to set up a partisan political organisation in the Kosovo, and a few National Liberation committees were formed. Contact was maintained with the Serbian, Montenegrin and Macedonian partisans, and in 1944 a conference was held at Kolgecaj which the Serbian and Montenegrin partisans attended.

4. Despite the lack of military activity in the Kosovo, Kosovo units fought from an early date with the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation both in Macedonia and Serbia under the command of the headquarters for these areas. In 1942, two Kosovo battalions formed in the hills west of Tetovo and fought with the 1st Macedonian Brigade until transformed into the 1st Kosovo Brigade, about 800 strong, in June 1944. At the start, it was composed mainly of fugitive Serbs, but in June 1944, it was estimated that some 30 per cent. were Albanians. Another Kosovo brigade, some 400 strong, formed probably in the Skopska Crna Gora, was, in the early part of 1944, in the area east of the Nis-Skoplje railway. Part of the Kosmet staff were located in Serbian territory south of the Radan, protected by a battalion of about 100 Kossovars. Not until the summer of 1944 did Kosmet start to take on a military character and in August, when it was in the Pec-Djakovica area, it was joined by the 1st Kosovo Brigade from Macedonia. The partisan forces in the Kosovo remained, however, weak, and failed to bring in with them any other resistance movements, of which the most important was built up by Gan Kryeziu, a Kosovo landowner from the Djakovica area. Relations between Kryeziu and Kosmet were correct and occasional military operations are thought to have been carried out together, but because of his failure to join them, Kryeziu incurred the dislike of Kosmet, who are believed to have threatened his life. Furthermore, the attempts of the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation to send troops into the Kosovo were not successful. The resistance put up by the Kossovar frontier guards was fanatical, and in May the 2nd Corps, attempting to break through Montenegro, and in July the Serbian forces of Lieutenant-General Popovic advancing from the north on to Gnjiline, were driven back. As a result of their almost complete failure in the Kosovo and of the brutality of the Kossovars towards the Serbs, the majority of the partisans took a pessimistic view of the possibility of winning over the Kossovars by conciliation. In general, the majority of the partisans, who had much to do with the Albanian minority during the war, such as General Vukmanovic Tempo, often stated that they were unregenerate bandits who must be brought to heel by harsh methods when the country was liberated. The Albanian minority in north-west Macedonia, many of whom belonged to the Bal Kombetar, were particularly regarded as brigands.

5. The fact that Kosmet was able to exist at all in the Kosovo was probably due to the support of the F.N.C. in Albania. So close was the liaison of Kosmet with the F.N.C. that British officers who penetrated the Kosovo at the end of 1943 believed Kosmet to be an offshoot of the F.N.C. The F.N.C. appear, however, to have recognised that Kosmet formed part of the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation rather than of their own forces and, during the summer of 1944, Hoxha publicly recognised Kosmet and recognised Kosovo as belonging to Tito's sphere of influence. From Macedonia, constant contact was maintained with the F.N.C. by Tempo and in the summer of 1944, joint operations were undertaken by units of the F.N.C. and of the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation against the Germans and Bal Kombetar in north-west Macedonia.

6. As the Germans began to withdraw and the power of the F.N.C. in Albania extended, the enemies of the F.N.C. movement were forced into the mountains adjacent to the Yugoslav frontier and many of them probably went over in the Kosovo and north-west Macedonia. F.N.C. forces moved after them towards and over the Yugoslav frontier.

7. From the Yugoslav side, the withdrawal of the Germans gave the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation their first opportunity to penetrate the Kosovo. At this time the persistently gloomy attitude of the partisans regarding the possibility of conciliating the Kossovars underwent a sudden change. There were mass desertions from Kosovo quisling units. Two new Partisan Kosovo brigade were formed by the end of October and two more were in formation. The Kossovars and the Albanians in north-west Macedonia were reported to be fighting the Germans as they withdrew. Meanwhile the partisan-Bulgarian assault on the Kosovo forced the Cetniks of the Skopska Crna Gora and to the south of Kopaonik, the latter under Zika Markovic, back into the Kosovo where they fought alongside the Germans and their Kossovar units. In southern Montenegro, partisan was reported to have driven some of the Cetniks of Djurisic to join forces with the Catholic chiefs of northern Albania in the area north of Lake Scutari. By the end of December, the enemy withdrawal, including about half of the Skanderbeg Division, accompanied them. The remainder of the Skanderbeg Division either deserted or were purposely left behind, and it seems probable that at least a part of the Cetniks stayed both in the mountains of the Kosovo and in the Sandjak. The Skopska Crna Gora was never completely cleared up by the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation and it is probable that about 1,000 Cetniks remain in the area. In the Kosovo and the mountain fringes around it there, therefore, remained a hard core of desperate resistance to the partisans, consisting of the remainder of the Skanderbeg Division and remnants of the southwest Serbian Cetniks of the Kopaonik who had so far compromised themselves as to have no hope of reconciliation with the partisans. In addition there were concentrated in northern Albania all the elements hostile to the F.N.C., and in villages of north-west Macedonia a backward population (unfriendly to the partisans) who had even before the war had a reputation for brigandry. It is also probable that some of the Djurisic Cetniks remained at large round the borders of Montenegro.

8. For some time after the occupation of the Kosovo by the partisans and Bulgarians, there were no reports of unrest. Serbian, Montenegrin and Macedonian garrisons were in many of the towns, and F.N.C. troops passed through the Kosovo on their way to Montenegro to help in the expulsion of the Germans from there. Subsequently there appears to have been a reduction of the garrisons in the area, and in February there were vague rumours of unrest. A circumstantial American report states that in February there was in the Kosovo an organised revolt inspired by the Bal Kombetar and involving 7,000 men, which was only suppressed by the use of six divisions of the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation. Apart from this one report there is little direct evidence of the revolt or of large movements of Yugoslav Army of National Liberation forces to counter it. In the middle of March, however, Dalmatian troops, together with tanks, were reported from several sources as passing through Albania on their way to Macedonia. From north-west Macedonia there were a number of reports of unrest. Early in February, the 49th Division was said to have been engaged in fighting near Kicevo, and on the 28th February, a band of Albanian Bal Kombetar irredentists attacked two E.L.A.S. battalions under the command of Gotsi (Slav-Macedonians previously operating in Greece) which had recently sought refuge from Greek Macedonia in the Gostivar-Kicevo area, killing 50 Greeks. Macedonian troops, together with Gotsi were reported to have taken counter-measures and defeated the Bal Kombetar. On the 2nd March, 200 Albanian prisoners were brought to Skoplje from Gostivar. All men between 17 and 30 in the Struga-Gostivar area were mobilised and a later report stated that the local commanders had been given the option of mobilising all men between 35 and 45. From one village in the Radusa area of 125 houses, it was reported that only eight men had been left. The morale of these troops was rather naturally low and a number were reported to have deserted, presumably with a view to joining the Albanian rebels. On the 29th March, bands led by Dzema and Mifail, operating in the Tetovo-Gostivar area, were reported to have moved to the Kosovo and Metohija to join the Cetniks and an Albanian leader called Djafer Bey in operations against the Yugoslav Army of National Liberation. Before leaving, they raided three villages in the Gostivar area and killed all partisan members of the National Liberation Committees. In reprisal for this, Macedonian units burned villages and removed all the men to the prison in Skoplje.

9. In the Kosovo, Miladin Popovic, Tito's early envoy to the Albanian partisans, was assassinated in Pristina on the 12th March. By the 1st April, Kossovar and Cetnik activity in the Kosovo was reported to be on the increase again and the 12th Macedonian Brigade was sent there from Skoplje to assist, according to the source, four other Macedonian brigades and a number of Serbian brigades already operating in the area. Trouble, seems to have continued in north-west Macedonia, and on the 7th April, two O.Z.N.A. (police) brigades appeared in Skoplje in answer to a request from the Macedonian Federal Government for reinforcements. The area, bounded by the Albanian frontier, Sar Mountains, Skoplje, Karabzica Mountains, Brod, Kicevo, and inclusive of Tetovo and Gostivar to Debar, was reported on the 16th April to be a war zone owing to the alarming proportions which the Albanian rising there had assumed. Large forces were engaged, including the 1st Skoplje Cavalry Brigade, the 8th, 9th and 16th Macedonian Brigades, and other unidentified troops from the Bitolj area. In addition E.L.A.S. troops under Gotsi in the Gostivar area were engaged in defensive fighting. 7,000 Albanians were alleged to have been imprisoned in Tetovo and large numbers of Albanians from the Skoplje area to have taken to the woods, 140 having deserted from the municipal power station in one day. In Skoplje itself there were continual rumours of Albanian trouble and 12,000 Albanians were stated to have been forcibly deported from the Kumanovo, Gnjiline and Vranje area to the Banat. There is little independent confirmation of these reports, but towards the end of March, there was talk in Belgrade of Albanians being marched northwards through the town under guard, and an American report of cases of typhus among Albanians in the Banat. From Split there were reports between the 5th and 8th April of the arrival of three parties of Kossovars, totalling about 2,000 men and some of them under guard, who were said to have been mobilised in the Kosovo to clear the area of troublesome factions after trouble in the neighbourhood of Pristina.

10. In recent conversations with members of my staff, General Velebit has confirmed that conditions have been disturbed in the Kosovo and attributed this mainly to the dropping of parachutists by the Germans. These, he said, were mainly drawn from the Skanderbeg Division. He maintained, however, that the trouble is now largely over, due in the main to the co-operation in the suppression of the rising of troops of the Albanian National Liberation Army whose lack of racial differences from the rebels and obvious sympathy with partisan aims has made a deep impression. The presence of troops of the Albanian National Liberation Army in the area is confirmed by an American report of the 25th March to the effect that the 5th Division of the Albanian National Liberation Army was in the Kosovo with its headquarters at Kosovoska Mitrovica. General Velebit said that in the north-west corner of Macedonia there was a certain amount of brigandage, but this had been the case even before 1941. The Minister for Macedonia made much the same comment.

11. The Skopska Crna Gora which was throughout the war a Cetnik and Albanian stronghold has also been reported to be a focus of trouble. As early as January one Macedonian battalion was reported engaged with Cetniks near Presevo, and there have been continual rumours of armed resistance there. At the beginning of April, the area was reported blockaded, and an eyewitness said that he had seen 200 well-armed Cetniks in a village ten miles from Skoplje. Later a report was received that one group of 4,000 men was at large there. It is believed that the recent rather chauvinistic attitude of the Macedonian Federal Government has caused much ill-feeling amongst the Serbs settled in Macedonia, and the main centre of Serbian resistance to the Macedonian regime is believed to be in the Skopska Crna Gora.

12. In a recent press report of a reception by Marshal Tito given to twenty-five delegates from the Kosovo and Metohija, who had come to attend the recent meeting of the Serbian Skupstina, headed by Mehmet Hoxha, President of the National Liberation Council for the Kosovo and Metohija, Marshal Tito made it abundantly clear that conditions in the Kosovo were not satisfactory, while the delegates spent much of their time in apologising for the shortcomings of the population. The Marshal stated that there was still a number of reactionaries and obscurantists not only in the Kosovo and Metohija but also in Albania, and when promising a fair redistribution of land, said that this would not be difficult since so many of the landowners in the Kosovo had worked for the enemy. He also spoke of cliques who had previously been working for the enemy and had now gone over to the enemy again. Contending that the reactionaries were only an active and vocal minority, he said that he was ready to grant an amnesty to those who were genuinely misled. When promising them Albanian schools and other minority rights, he pointed out that they could expect no rights without performing their duties, and stressed the importance of their mobilisation into the Yugoslav army. He urged the Kossovars to wipe out the blot on the reputation of the Kosovo themselves. He pointed out that with many of the dissidents, it would be enough to try to convince them of the rightness of the partisan cause since they had merely come to the Kosovo because they could not be convinced. He said that they must use strong measures to correct this attitude. It seems possible that this was an oblique reference to the move to the Kosovo of the main anti-F.N.C. elements in Albania, a fast which may be borne out by the movement of F.N.C. troops there. The Albanian delegates did not deny the existence of subversive elements, but pleaded in extenuation that they were largely due to lack of education.

Gani Bey Kryeziu,

d. 1952

13. The recent arrest of Gani Kryeziu, who throughout the war, except when interned by the Italians, was in active opposition to the enemy, also bears witness to the present regime's fear of any leader, around whom opposition could centre.

14. That the Albanians of the Kosovo should, after their years of ill treatment at the hands of the Yugoslav Government, welcome incorporation in the Yugoslav State without any resistance, particularly after the clever play which the Germans have made with their irredentist aims, was too much to expect. That there has been serious resistance is clear, though whether the main strength of the armed resistance has been broken is not. It seems probable, however, that large-scale mobilisation and deportation to other parts of the country as well as the arrest of possible leaders such as Kryeziu have at least temporarily paralysed it. The announcement of the future adherence of the Kosovo and Metohija to the Serbian federal unit may possibly resuscitate it, but it seems probable that such an announcement would not have been made unless the Government felt that the sting of Albanian resistance had been drawn.

15. In the wild country of north-west Macedonia, it seems that Albanian resistance continues, but the despatch of one of the recently arrived O.Z.N.A. brigades to the Bitolj area may mean that this is on the wane. There is some evidence that Cetnik bands have been operating with the Kosovo rebels near the Albanian frontier, but their main stronghold is probably the Skopska Crna Gora, though a few may be at large in the Kopaonik, where parachutists were recently dropped to them by the Germans. These were reported, however, to have been so easily rounded up that it seems improbable that the resistance forces there are very considerable.

16. In the Sandjak, there has been talk of a resistance movement, presumably Cetnik, called the "White Eagles" (Beli Orli), but confirmation of their existence is so completely lacking as to make it appear probable that they are a mythical force.

17. It is improbable that either the Kosovo, Skopska Crna Gora or even the Kopaonik or Sandjak could be the rallying ground of disaffected elements from other parts of Serbia. With the possible exception of the Sandjak, they are far from the centre of Serbia, and the access of large numbers of men to them from other parts of Serbia would be difficult. The Sandjak, considering the size of its population, has throughout the war played a prominent part in the partisan movement, and it seems unlikely that a resistance movement could exist there. Moreover, to put up effective resistance, the Albanian and Serbian rebels would have to join forces, particularly as it seems probable that the only area where there is a sufficient core of resistance to allow rebellion any hope of success is the Kosovo and north-west Macedonia. Such is the dislike and scorn with which the average Serb regards the Albanians, that it is scarcely likely that the Serbs would, even if they could consider doing this. It is only those Serbs who have in the course of years of fighting against the partisans so compromised themselves as to make it hopeless for them to seek pardon from the new regime, who have resorted in desperation to this alternative to certain liquidation.

18. I am sending copies of this despatch to the Resident Minister, Central Mediterranean; His Majesty's Ambassador in Athens; Lieut.-Colonel Clarke, 37 Military Mission, in Bari; and to the British Delegation in Belgrade.

I have, &c.

RALPH SKRINE STEVENSON

[from: Bejtullah D. Destani (ed.), Albania & Kosovo: Political and Ethnic Boundaries, 1867-1946. Documents and Maps. Slough: Archive Editions, 1999, p. 939-944.]

TOP