| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

Count Galeazzo Ciano,

Italian Foreign Minister (1936-1943)

(from Ciano's Diary, 1939-1943

[London 1947])

1947

Galeazzo Ciano:

Diary of Events on AlbaniaItalian political figure and diplomat, Galeazzo Ciano (1903-1944), was born in Leghorn as the son of an admiral, Count Costanzo Ciano, who was a founding member of the National Fascist Party. He studied law in Jena and entered the diplomatic service in 1925, serving as attaché in Rio de Janeiro. On 24 April 1930, he married Benito Mussolini’s daughter, Edda Mussolini (1910-1995), which did much to further his political career. He subsequently served as Italian consul in Shanghai (1930) and as press spokesman (August 1933) and minister of propaganda (1935). He took part in the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935-1936 as a pilot and, returning from the campaign as a ‘hero’, he was appointed Italian foreign minister in 1936, replacing Mussolini. Ciano was the prime figure behind the Italian invasion of Albania in 1939, which he had worked hard to persuade the Duce to undertake. After the conquest, he embarked on the further invasion of Greece, from Albania, that soon turned into a fiasco. On 8 February 1943, after political disagreements with the Duce, Count Ciano was relieved of his post as foreign minister and was demoted to ambassador to the Vatican. Italian forces capitulated in Albania on 8 September 1943. By this time, Ciano, having supported the ousting of Mussolini at a meeting of the Fascist Grand Council on 24 July 1943, had fled to Nazi Germany. The Nazis returned him to Italy, where he was arrested, tried in Verona for betraying Mussolini, now head of a puppet government in northern Italy, and shot in the back at the latter’s behest on 11 January 1944. Ciano’s diaries of the war years miraculously survived, smuggled into Switzerland by his widow, and contain much material on Albania. They were first published in English by Malcolm Muggeridge in the volume “Ciano’s Diaries, 1939-1943” (London 1947). The following excerpts, taken from this diary, are first-hand and surprisingly candid views on political events in Albania from January 1939 to January 1943.

JANUARY 15, 1939

I discussed with the Duce what I must say and do in Yugoslavia. The Albanian question was the principal point of the discussion. We agreed that it would not pay to gamble with our precious friendly relations with Belgrade to win Albania. Therefore, as things stand, we shall take action only if we can arrive at an agreement on the following basis: adjustment of the Yugoslav frontiers, demilitarization of the Albanian frontiers, military alliance, and absolute support of the Serbs for their conquest of Salonika.JANUARY 16, 1939

Conference with Sereggi, bearer of a letter from King Zog, who asks for mediation with the Yugoslavs regarding the treatment of the Albanian minorities living in Kossovo; if everything goes well, and if Stoyadinovich is able to proceed with determination, I shall certainly give Zog the mediation he asks for!JANUARY 19, 1939

Arrival at Belje. Hare hunt. I returned by train, and Stoyadinovich and I had a conversation. I touched on the Albanian question. At first Stoyadinovich seemed perturbed. Then he broke the ice, and spoke of the partition of Albania as the best way out.JANUARY 22, 1939

No definite news about the Yugoslav crisis. The Duce said that this is another proof that we can do business with one country alone, that is, with Germany, which, like ourselves, is not changeable in its directives and in the obligations it assumes. Stoyadinovich’s position seemed to be secure; he himself asserted a fortnight ago that nothing and no one could get him out of power. Now, things are different. Now, the crisis interests me, not so much because of our relations with Belgrade, which will not change very much in the immediate future, but rather with regard to Albania, about which we had almost reached an agreement. Anyway, the following formula was agreed upon with the Duce: if the Stoyadinovich policy still holds, to go ahead with the partition of Albania between us and Yugoslavia; if not, then occupation of Albania by us without Yugoslavia, and, if necessary, even against Yugoslavia.FEBRUARY 6, 1939

I saw the Duce at the Palazzo Venezia. He believes that the dismissal of Stoyadinovich is a veritable coup d’état on the part of the Regent, who wanted to prevent the strengthening of the Fascist dictatorship in Yugoslavia. I gave the Duce my point of view on Albania: we must work faster. He agreed with me. We shall begin immediately to mobilize land forces and to concentrate air forces. We shall intensify local revolutionary preparations. The date of the action: Easter week.FEBRUARY 7, 1939

During the evening I saw the Duce, and we spoke at length about the situation. I repeated my views on the necessity for acting more quickly in Albania for the following reasons: (i) the Yugoslavs now know that we are considering the question, and the rumour may spread; (2) with the removal of Stoyadinovich the Yugoslav card has lost for us 90 per cent of its value; (3) since the enterprise will no longer be undertaken in conjunction with Yugoslavia, but without her, and perhaps even against her, we must not give her time to strengthen her political, diplomatic and military contacts with France and with Great Britain. Barring unforeseen circumstances, the Duce agreed that the date for the attack should be between April 1st and 9th. In the meantime, I will see Ribbentrop, and perhaps give him an account of the matter.FEBRUARY 10, 1939

Great resentment over Germany’s intention to lay hands on the Albanian oil. The evidence comes from an official communication received by Attolico. I telephoned Mackensen and informed him that we considered Albania as just like any other Italian province, and that any German intervention would create strong resentment in Italian public opinion. This fact also proves that the Albanian boil will come to a head in a short time. The Serbians have spoken. King Zog is alarmed and very much agitated. Some move might yet be made to oppose our action.FEBRUARY 11, 1939

I received von Mackensen, who gave me the following explanation about the Albanian oil question. They had received a proposal, but nothing had been done, and nothing would be done. The haste with which the answer was given was a proof of German eagerness to dispel any mistrust inside the Axis.FEBRUARY 14, 1939

The Duce said that with regard to Albania we must await two events: the settling of the Spanish affair, and the alliance with Germany. In the meantime, we must spread the most varied rumours; like the octopus we must darken the waters. With regard to France, he repeated that it is desirable for the moment to await the development of Baudouin’s undertaking. If there are no developments, we shall put the question: Will you or will you not do business? If not, we shall prepare for war without delay. He again told me that we are in possession of a secret weapon which, “though not miraculous, could, none the less, affect the course of the war”.FEBRUARY 16, 1939

Albania is restless. We have received a telegram from our military attaché at Tirana which has somewhat disturbed the Duce; he said that King Zog wanted to order partial mobilization, and that Jacomoni had left by air for Rome. The situation is not so dramatic as all that. I have seen Jacomoni, who, in fact, appears quite calm. Yesterday he saw the King, who, after having listened to our complaints, said that he, too, had something to say. He asserted that in Belgrade the partition of Albania had been discussed, but he mentioned certain particulars which show that he was only partially and incorrectly informed. He also mentioned the preparation for an internal revolt, supported especially by refugees - a statement which was completely false. He cited the names of many people who were involved; except for Koci, these names were incorrect. He concluded by reaffirming his desire to reach an understanding with us, and he sent Jacomoni as his representative with full powers to make the agreement. When I reported to the Duce by telephone he answered: “If we had already signed our Pact with Berlin we could attack immediately. As things stand, we have to procrastinate.” Then he confirmed the instructions which I had already sent to Jacomoni two days ago, which are as follows: to keep alive the popular agitation, but not to fail to placate King Zog, giving him every reassurance he desires. To keep the waters troubled, so that our real intentions will not be known.FEBRUARY 21, 1939

Jacomoni referred to the Albanian situation: the King and his supporters have declared formally that they wish to re-establish the most cordial relations with us, but Jacomoni fears that this may be a manoeuvre to gain time for the King to proceed with his attempts to come to terms with other Powers. Jacomoni feels that the situation should be brought to a head at once. The Duce and I do not agree with him. I instruct him by telegraph to steer cautiously for some time yet, while we are waiting for certain international events which will make it easier for us to deliver our blow.MARCH 5, 1939

Jacomoni assured us that order has returned in Albania, and that the King, after having had the greatest scare of his life, goes to extremes in demonstrating his friendship for us. He has sent me his “fraternal” greetings. The fact is that none of the actors has talked, and that the play has only been postponed.MARCH 15, 1939

Events are precipitated during the night. After a meeting between Hitler, Hacha, and Chwalkosky, German troops began their occupation of Bohemia. The thing is serious, especially since Hitler had assured everyone that he did not want to annex one single Czech. This German action does not destroy the Czechoslovakia of Versailles, but the one that was constructed at Munich and at Vienna. What weight can be given in the future to those declarations and promises which concern us more directly? It is useless to deny that all this worries and humiliates the Italian people. It is necessary to give them satisfaction and compensation: Albania. I spoke about it to the Duce, to whom I also expressed my conviction that at this time we shall find neither local obstacles nor serious international complications in the way of our advance. He authorized me to telegraph to Jacomoni, asking him to prepare local revolts, and he personally ordered the Navy to hold the second squadron ready at Taranto.I conferred with Cavagnari, and after having given telegraphic instructions to Tirana, I was able to speak by telephone with Jacomoni, who was on his way to headquarters. He said that to-morrow he will telegraph us what he thinks can be done. He foresees handing this ultimatum to the King: either he accepts the arrival of the Italian troops and asks for a protectorate, or the troops will arrive anyway. I conferred again with the Duce, and he seemed to me to be less cool about the operation.

I saw the Duce again in the late afternoon. He is fully aware of the hostile reaction of the Italian people, but he affirms that we must, after all, accept the German trick with good grace and avoid “displeasing God and also God’s enemies”. He mentions again the possibility of a blow in Albania, but is still doubtful. Even the occupation of Albania could not, in his opinion, counterbalance in world public opinion the incorporation into the Reich of Bohemia, one of the richest territories of the world. Furthermore, to Admiral Cavagnari, whom the Duce received before me, he put only general questions regarding the possibility of making a landing, but did not give instructions of any kind. Too bad! I am convinced that our going into Albania would have raised the morale of the country and would have been an effective result of the Axis policy, after which we could have re-examined our policy with regard to Germany, whose hegemony begins to be disturbing.

MARCH 16, 1939

Mussolini called me to the Villa Torlonia at nine o’clock in the morning. He looked sullen. He said that he had thought a great deal during the night, and that he had come to the conclusion that the Albanian operation must be postponed because he fears that, disturbing the unity of Yugoslavia, it might favour an independent Croatia under German rule, which would mean that the Ustasci would be in Sussak. It is not worthwhile to take this risk in order to get Albania, for we can have her at almost any other time. I can see that Mussolini has made up his mind; no use insisting. I ordered Jacomoni to let everything rest. I kept a note written by the Duce, in which he lists the reasons for the postponement of the Albanian action.MARCH 23, 1939

The Duce has decided to move more rapidly on the Albanian question, and he himself has drafted the projected agreement, which is very brief, consisting of three dry clauses which give it more the appearance of a reprieve than of an international pact. I am also preparing one with Vitetti. It is an accord which, though couched in courteous terms, will permit us to effect the annexation of Albania. The Duce has approved it. Either Zog accepts the conditions which we lay before him, or we shall undertake the military seizure of the country. To this end we are already mobilizing and concentrating in Puglia four regiments of Bersaglieri, an infantry division, air force detachments, and all of the first naval squadron.Chamberlain has sent a letter to the Duce. He expresses his concern over the international situation and asks the Duce’s help in re-establishing mutual trust and ensuring the continuance of peace. Mussolini will answer after striking at Albania. This letter strengthens his decision to act because in it he finds another proof of the inertia of the democracies.

MARCH 24, 1939

Discussed with the Duce and Pariani our plan for action in Albania. We agreed that it is not advisable to send an ultimatum immediately, but rather to begin our negotiations with King Zog. If he tries to resist, or to outwit us, we will use force. The Duce was concerned about reactions in Belgrade, which must, for many reasons, be minimised.MARCH 25, 1939

De Ferraris left for Tirana taking with him the draft agreement for the protectorate. It is not yet possible to foresee what the developments will be, but it seems probable that King Zog will give in. There is, above all, a fact on which I am counting: the coming birth of Zog’s child. Zog loves his wife and indeed his whole family very much. I believe that he will prefer to ensure a quiet future for his dear ones. And, frankly, I cannot imagine Geraldine running around fighting through the mountains of Unthi or of Mirdizu [Mirdita] in her ninth month of pregnancy.MARCH 28, 1939

De Ferraris has returned from Albania with a memorandum from Jacomoni. It seems that the King is up to some sort of trickery. His answer is yes, and then he arranges for his ministers to say no. Nevertheless, the machine is in motion and can no longer be brought to a stop. Either it will function with Zog or else against him. For many reasons, primarily because we Italians do not want to be the ones to start a war in Europe, I should prefer the first alternative, but if Zog does not yield it will be necessary to have recourse to arms.Demonstrations in the Piazza Venezia because of the fall of Madrid. The Duce is overjoyed. On pointing to the atlas open at the map of Spain he said: “It has been open in this way for almost three years, and that is enough. But I know already that I must open it at another page.” He has Albania in mind.

MARCH 29, 1939

I had two meetings with the Duce in order to make decisions regarding Albania. Since he is leaving for Calabria, and will return on Saturday, he insisted on bringing the matter up to date. (1) The Army, Navy, and Air Force continue their preparations. They will be ready on Saturday. (2) Jacomoni must, in the meantime, exert diplomatic pressure on the King, reporting its effects. (3) At a certain point, unless he gives up before this, we shall send our ships into the territorial waters of Albania and present an ultimatum. (4) If he persists in his refusal we shall raise the tribes in revolt, publish our declarations, and land. (5) Having occupied Tirana, we shall gather the Albanian chiefs into a constituent assembly, over which I shall preside, and offer the crown of Albania to the King of Italy.No one will protest. Not even Yugoslavia, which is too pre-occupied with recent events in Croatia. This evening I talked at length to Christic: I gave him ample assurances regarding Croatia, but made reservations regarding Albania. He offered no objections; he proposes, as a condition, that Albania shall not be used for an attack on Yugoslavia.

Badoglio went to the Duce to say that he was in agreement with him on the Albanian undertaking; his only suggestion was that larger forces should be mobilized. We shall mobilize an additional division, and also a battalion of tanks.

MARCH 31, 1939

After a long series of more or less useless discussions with, among others, Spoleto and Suardo, I had a meeting with Pariani, Jacomoni and Guzzoni, who has been appointed commander of the expeditionary force in Albania. Jacomoni had no particular reasons for coming to Rome, except perhaps that by his absence he would introduce a little calm into the atmosphere of Tirana, which by his time is very disturbed. It would appear that the King has decided to refuse to sign a treaty which formally and substantially violates the integrity and sovereignty of Albania. Pariani said that he preferred such a determined attitude which permits a final settlement of the Albanian question. We studied the military plan of campaign and its close co-ordination with the diplomatic moves. It appears that this co-ordination is possible. But Jacomoni returned in the afternoon after his meeting with the military chiefs to give me his disquieting impressions regarding the organization of the expeditionary force. It appears that they cannot, by all their efforts, put together a battalion of trained motor-cycle troops, which could make a surprise arrival in Tirana. Unforeseen difficulties arise also with regard to the landing operations. In the meantime, news from Tirana confirms the fact that the King is preparing to resist – a matter which annoys me greatly, because I consider it rather dangerous to fire the first shot in this disturbed and inflammable Europe. The Duce will arrive to-morrow afternoon, and until then his decisions cannot be altered. While waiting I instructed Jacomoni to prepare a draft treaty which in his opinion might be accepted by King Zog.APRIL 1, 1939

The Duce returned and I had a preliminary conference with him, Jacomoni present. He approved the outline of the treaty with some slight modifications, which are more matters of detail than of substance, but which will have the effect of saving the King’s face. For an Oriental, this means a lot. We planned this line of action: to-morrow Jacomoni will appear before the King with a new outline of the treaty and will make it clear that the situation is now serious. Either he will accept, and in that case I will go to Tirana to attend the solemn ceremony of signing the treaty, naturally accompanied by a strong squadron of planes, which will be a symbol of the fact that Albania is Italian. Should he refuse, disorders will break out in all of Albania on Thursday, making armed intervention on our part an immediate necessity. In this case, we shall land on Friday morning.During the afternoon Sereggi, the new Albanian Minister, came to see me. He begins his mission at a stormy time. Passing by Bari, he saw the concentration of troops and realized that the music was about to begin. I spoke frankly to him; in a friendly tone but quite firmly. He said that he was in agreement with us. He urged me to save appearances in such a way as to make the solution acceptable to the King and to the people. I accompanied him to the Palazzo Venezia, where the Duce repeated the warning in more precise terms. He added that if the King should refuse to sign the pact, a crisis will be unavoidable. Sereggi decided to leave for Tirana with Jacomoni, in order to persuade the King. Then, on the pretext that he was not able to exchange his Albanian money, he asked Jacomoni to lend him 15,000 lire, a first instalment on a bribe!

APRIL 2, 1939

Muti arrived in Rome, and I got ready to send him to Tirana with a small band of men as enterprising and boastful as himself, in order to create the incidents which are to take place next Thursday evening if the King, in the meantime, has not had the kindness to capitulate. I gave him freedom of action, but he is under definite orders: to respect the Queen and the child, if it is already born; to create terror during the night; at daybreak to hide in the woods and await the arrival of our troops, trying, in the meantime, to impede Zog’s retreat toward Mati, where he might attempt some resistance.The reactions in the various capitals, including Belgrade, are mild. Christic, on the other hand, is more alarmed, but in answer to a question he declared himself convinced that the Albanian question cannot change the relations which happily exist between Rome and Belgrade. He recommended that no action be taken without first informing Belgrade, and that somehow the existence of the Albanian State should be preserved as a matter of form.

Many contradictory news dispatches during the morning. Jacomoni telegraphed an Albanian counterproposal presented before the Duce’s ultimatum, but we did not take it into consideration. Sereggi telegraphed to offer his resignation. From Durazzo [Durrës] and Valona [Vlora] news arrived that the embarkation of Italian refugees is proceeding normally. Fortusi and the aviator Tesei, who arrived at noon from Tirana, said that the exodus of the Italians had filled the population with terror. They crowd the streets, weeping, and accusing King Zog of having brought this calamity upon them. The Duce telephoned the order for the embarkation, saying that the order for departure would come during the evening. At my suggestion he decided to carry out a demonstration flight by a hundred planes over Durazzo, Tirana, and Valona this afternoon.

4 p.m. A telegram arrived from Jacomoni. It appears that the King does not wish to take upon himself the responsibility for a complete capitulation, and intends to convoke the Council of Ministers to take the final decision of resisting or giving up. Quite justly, Jacomoni observed that, in this way, the King puts himself outside the terms of the ultimatum, but he agreed to transmit the information, none the less.

The Duce, whom I have informed, gave the order to launch the expedition, reserving the right to make public the news of its progress, if any.

From the telegraph offices we learn that long code messages are going from Tirana to the British Foreign Office. We cannot stop them. I gave orders, however, that they be delayed, and that many errors in the code groups be repeated. It is worth while gaining time, even though Chamberlain gave the House of Commons an account of what has happened which was very favourable to us, and has also declared that Great Britain has no specific interests in Albania.

7 p.m. Jacomoni telegraphed saying that he was burning the secret code, that he had told the officials of the naval mission to leave, and that the entire Legation might have to get on the submarine which is at Durazzo. The Duce repeated the order to attack, while specifying that the Air Force must spare the cities and the civil population.

Badoglio has written a letter to the Duce criticizing the plan of operations. The Duce paid no attention to it. In a letter the King takes note of the communication made by the Duce yesterday, but expresses his doubts regarding the possibility of our installing ourselves solidly in Albania, basing his opinion on historical memories of the Venetians and the Aragonese. Evidently he does not remember that the Romans installed themselves there very well.

9 p.m. I communicated to Villani and to von Mackensen our decision to proceed with the military occupation. I received assurances from them both as to their solidarity and their absolute understanding of the motives which made us act. Subsequently I saw Christic. I acquainted him with the manoeuvres to create a crisis between us and Belgrade. I gave him the fullest assurance regarding the extent of our action and commitments. It seemed to me that he took it all with remarkable resignation. As he went out he said: “So Zog is coming to the same end as Benes.”

At last Albanian proposals arrive. They would like to deal with Pariani. This is not possible, especially since Pariani is in Germany. We answered that eventually we shall send a plenipotentiary.

I returned home at about 10.30 p.m. I am tired and don’t feel well. I should like to rest, especially since to-morrow I must make a flight in order to observe the landing of our forces. Nothing to be done about it.

At dawn Zog’s son was born. How long will he be the heir to the Albanian throne?

APRIL 5, 1939

Two ships will go to Valona and Durazzo to evacuate the Italians, who are now seriously threatened by the bandits to whom Zog has given orders to start a reign of terror. For the time being international public opinion is calm, so calm that I suspect it does not realize the tension between us and Zog and thinks Zog is going to appeal for help. Germany, meanwhile, behaves well. Von Ribbentrop has communicated to Attolico that Berlin looks upon our action at Tirana with sympathy since any Italian victory represents a strengthening of the power of the Axis. Budapest has also reacted well. Villani informs me that six Hungarian divisions already mobilized are ready to go to the Yugoslav border at forty-eight hours notice if it should be necessary to exert pressure on the Serbs.I saw the Duce several times. He is calm, frightfully calm, and more than ever convinced that no one will want to interfere in our affair with Albania. However, he has decided to march, and he will march even though all the world may be pitted against him. He repeated this aloud to Muti, who has hurried to Tirana and confirmed our impression that Zog will resist with the small forces which he has at his disposal. Inasmuch as the King requests twenty-four hours so that he can think the matter over, the Duce, through a personal telegram, fixed the expiration of the ultimatum for twelve o’clock Thursday, April 6th.

APRIL 6, 1939

Christic asked for another appointment. He seemed to want to say something urgent and serious to me. I was afraid that it was going to be a change in the policy of Yugoslavia. Instead, it was a question of new requests for clarification and for details about our action and our future programme. I tendered the olive branch. Christic himself, on telephoning to Belgrade, showed satisfaction over what I had said to him.APRIL 7, 1939

I got up at 4 a.m. Starace was waiting for me in the entrance hall with many communications, among which was a telegram from Zog to the Duce. It confirmed his decision to arrive at a military understanding and asked for negotiations. We answered that he should send his negotiators to Guzzoni. The Duce, having got up during the night, which is a very unusual thing, would like to have news and explanations that I am not in a position to give him because I have none.

Count Ciano in Durrës, 7 April 1939The military attaché, Gabrielli, who in the last few days has behaved very strangely, telegraphs that Zog has at his disposal 45,000 men. I have the impression that he is exaggerating.

At 6 a.m. I left by plane. The weather is calm and warm. Buti, Vitetti, and Pavolini came with me. We were at Durazzo at 7:45. It was a beautiful spectacle. In the bay, motionless and solemn, were the warships, while motor-boats, lighters, and tugs moved in the port, transporting the landing forces. The sea was like a mirror. The countryside is green and the mountains, which are high and massive, are crowned with snow. We saw only a few people in Durazzo. But there must have been some resistance because I saw detachments of Bersaglieri, crouched behind piles of coal, defending the port, and I saw others going up the hill in Indian file in order to surround the city.

From some of the windows there was occasional firing. I continued to Tirana. The streets were deserted and undefended. In the capital the crowd moved through the streets quite calmly. The Legation was barricaded. On the roof was a large Italian tricolour flag and in the court-yard many vehicles. I was convinced that in case of danger it would be easy to defend it from above and I gave orders to this effect.

I reported to the Duce, who was quite satisfied, particularly because international reaction was almost non-existent. The memorandum which Lord Perth left with me in the course of a cordial visit might have been composed in our own offices.

During the afternoon everything changed. Guzzoni received Zog’s negotiators, and instead of proceeding as the Duce had ordered, suspended everything for six hours. The Duce was furious, because this delay might have serious consequences. It is necessary for us to arrive in the capital in order to carry out our political manoeuvring. Through Valle, the Duce ordered the march to be resumed, but meanwhile a day has been lost and this permits the usual mud-slinging French press to say that the Italians have been beaten by the Albanians. News about the advance of the columns is lacking. The only one who telegraphs is Jacomoni, who is hiding with other Italians in the Legation. The information he sends gives rise to more and more concern about its fate; the bandits are ransacking the royal palace and threaten the Legation. The Duce, in a very nervous state of mind, telephones continually during the night, demanding information which I am unable to give. Only in the early hours of the morning does Jacomoni indicate that the city has quieted down, but we do not know anything about Guzzoni’s advance.

APRIL 8, 1939

D’Aieta telephoned at eight o’clock in the morning, saying that Jacomoni gives every assurance that the airfield at Tirana is usable. I decided to leave immediately, and I informed the Duce, who approved. I arrived in Tirana at 10:30, after having flown over the armoured column, which is marching on the Albanian capital. The forward elements are already at the gates of the city. I found Valle, Guzzoni, and Jacomoni on the field, together with many units of airborne grenadiers. I must admit that a violent emotion has taken possession of me and of everybody else. I saw Guzzoni, who explained the reasons for the delay: landing difficulties, fuel not adaptable, and, finally, lack of communications, because the radio operators are not up to the mark. The situation is now excellent. I received many Albanian delegations which paid me homage. In reply I said that Italy will respect Albanian independence, ensuring her political development as well as the social and civil rights of the people. With the news of Zog’s flight to Greece vanish all our fears about resistance in the mountains. In fact, the soldiers are already returning to their barracks, after having deposited their arms in the garden of the Legation. I gave orders that the soldiers should be treated well, and especially the officers. I took some steps towards re-establishing order and the normal rhythm of civilian life. I gave orders that all of Zog’s political prisoners should be freed. These prisoners had been sentenced to one hundred years in gaol. I distributed money to the poor. I conferred with the leading citizens of Tirana, in order to get a definite idea of the wishes of the Albanians and also to make decisions regarding the new form of government to be given to the country. Mixing with the troops and their officers, I found them all very proud of the undertaking.APRIL 9, 1939

I return to Rome to confer with and make a report to the Duce. Many Albanians greet me on the airfield with considerable cordiality. They give me Albanian flags and ask for Italian flags in return. This morning Tirana is decorated with Italian tricolour flags.The Duce is happy. He listens attentively to my report and decides to send a congratulatory telegram to General Guzzoni. He really deserves it.

Regarding the new Albanian regime, the Duce has planned a regency, which does not seem good to me. I tell him so, and explain my plan as follows: to create at once a government council, and announce a Constitution by April 12th; to arrange for the voting of a decision which will sanction the union of the two countries, conferring on King Victor Emmanuel III the crown of Albania. In principle he approves. During the afternoon I draw up the document and discuss it with some jurists and other minor officials, such as Buti, Vitetti, et al. All agree that while such a decision will give us possession of Albania it will not look like aggression. This is useful, the more so because our tension with Great Britain appears to be decreasing after a conference I had this morning with Lord Perth; and the Yugoslavs behave in such a friendly way because of their boundless fear. The same may be said of the Greeks.

APRIL 10, 1939

Reaction abroad begins to lessen. It is clear above all that the British protests are more for domestic consumption than anything else. News from Albania is good; military occupation is carried out according to plan and without obstacles.

We examine with the Duce the project drawn up yesterday, which is approved, except for a few minor variations in the wording. Programme: the announcement of the Constitution at Tirana on the 12th, the Grand Council in Rome on the 13th, my speech to the Chamber on the 15th, and Sunday, the 16th, a great national celebration of the event.APRIL 11, 1939

I got to work on the preparation of the speech for the Chamber. The protests of foreign countries have toned down; with to-morrow’s ceremonies we shall give the democracies a good pretext to wash their hands of the whole affair, than which they ask for nothing better.I communicated to Pignatti the Duce’s decision to erect a mosque in Rome in view of the fact that 6,000,000 Italian subjects are now Mohammedans. After having spoken with Maglione, Pignatti reported to me that at the Vatican they are horror-struck at the idea, which they take to be contrary to Article I of the Concordat. But the Duce has made up his mind, and he is supported in this by the King, who always takes the lead in any anti-Church policy. Personally, I do not see any need for such a thing, and, at any rate, I would be more inclined to have this mosque constructed in Naples, since that city constitutes a veritable bridge with our African domains. In so far as this proposal concerns the Albanians, we realize that they are an atheistic people who would prefer a rise in salary to a mosque.

APRIL 12, 1939

I arrive at Tirana by plane at 10:30 and am received at the airport by members of the new Albanian Government. I did not know Verlaci and, had I known him, I should have opposed his nomination. He is a very surly-looking man and will give us a great deal of trouble. The crowd receives me triumphantly; there is a certain amount of coolness, especially among the high-school students. I see that they dislike raising their arms for the Roman salute, and there are some who openly refuse to do it even when their companions urge them.However, things are not going so smoothly as it might appear. There is a great deal of opposition to union. All are in agreement on having a prince of the House of Savoy or, better still, they would like to have me. But they understand that giving the crown to Victor Emmanuel III means the end of Albanian independence. I have long discussions with many chiefs; the most stubborn are those from Scutari [Shkodra] (who have been incited by the Catholic clergy). It will be easy to convince them, however, as soon as I distribute bundles of Albanian francs, which I have brought with me. Nevertheless, things go well during the meeting of the electoral body; there is a unanimous vote which is also very enthusiastic. They come as a delegation to bring me their decision. I speak from the balcony of the Legation, and am especially successful when I give assurance that the decision will prejudice neither the form nor substance of Albanian independence. Let it be understood that this success refers to the masses, because I see the eyes of some patriots flaming with anger and tears running down their faces. Independent Albania is no more.

APRIL 13, 1939

I return to Rome and go at once to the Palazzo Venezia. I find the Duce on the roof observing anti-aircraft experiments. I inform him of what has happened. He would like to go further at once and abolish the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Albania. I do not share his views. We must proceed gradually unless we want to antagonize the rest of the world. So far matters have run smoothly because we have not had to have recourse to force, but if to-morrow we should begin firing on the crowd, public opinion would become excited again. On the other hand, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs is of use to us, since it will make the new regime acceptable without going through interminable legal arguments about its recognition. Later on it can be quickly suppressed. I propose to the chief of the Albanian Government the creation of an under-secretary for Albanian affairs and name Benini as under-secretary. I want a technical expert because it will be necessary to carry out a programme of public works quickly. Only thus will we definitely link the people to us and destroy confidence in the authority of their chiefs, showing that only we are capable of doing what they have not been to do or did not want to do themselves.During the evening a short Session of the Grand Council for the approval of the decree.

APRIL 15, 1939

The Albanians have arrived. Some of them have a depressed air. The Duce received them at the Palazzo Venezia and addressed them. I noted that they listened anxiously for the word “independence”, but this word did not come, and they were saddened. Jacomoni confirmed this later.APRIL 16, 1939

The ceremony of offering the Albanian crown to the King of Italy takes place at the Royal Palace. The Albanians, who seem to be lost in the great halls of the Quirinal, have a depressed air. Verlaci especially appears depressed as he pronounces, with a tired air and without conviction, the words he has to say in offering the crown. The King answers in an uncertain and trembling voice; he is certainly not an orator who makes any impression on an audience, and these Albanians, who are a warrior mountain people, look with amazement and timidity on the little man who is seated on a great gilt chair beside which stands a gigantic bronze statue of Mussolini. They cannot understand what this is all about.I talked to the Duce about the state of mind of the Albanians. He, too, was aware of it, and he assures me that he will talk to them to-day about their national independence and sovereignty in a way that will send them home reassured.

APRIL 18, 1939

We begin to draw up our plan of action in Albania with Benini. I think it will be successful since he is a man of action and is clear in his ideas and in his judgment. The Duce, too, was favourably impressed by him.APRIL 19, 1939

Conversation with Perth. The British raise some difficulties connected with the title: King of Albania. Some lively arguments with Perth, in which I maintained that the change in the dynasty is a matter of internal affairs in which no one has a right to interfere.APRIL 21, 1939

A day particularly devoted to Albania. I have a conference with Shtylla, formerly Albanian Minister in Belgrade. He gives information especially regarding the problem of the Kossovars, 850,000 Albanians, strong, resolute and enthusiastic for a union with their mother country. It seems that the Serbs are in a panic over it. For the moment we must not even allow it to be imagined that the problem is attracting our attention; in fact we must give the Yugoslavs a dose of chloroform. Later on it will be necessary to adopt a policy of real interest in the Kossovo question; this will create an “irredentist” problem in the Balkans that will absorb the attention of the Albanians themselves and will be a dagger thrust into the back of Yugoslavia.In the afternoon a meeting of Ministers to pass the budget of the under-secretariat for Albania. It is fixed at 430,000,000 lire. Although I protested strongly against it, I am convinced that this sum will suffice.

At the Palazzo Venezia I see Lord Perth. The Duce has treated him very courteously and seems to like him now. It has been decided that we will accept the credentials of his successor without the title of King of Albania.

APRIL 22, 1939

In Venice for the arrival of Markovic. The population gives me a cordial welcome. Evidently the Albanian question has had a particular echo in this great Adriatic city. Markovic makes a good impression on me. He is a kindly, temperate, and modest man. He has all the characteristics of the career diplomat. The arrival in Venice was a great event for him. This is the first time he has travelled abroad as a Minister. The applause, the flags, the bands, and an enchanted Venice full of sun and springtime have deeply moved him.

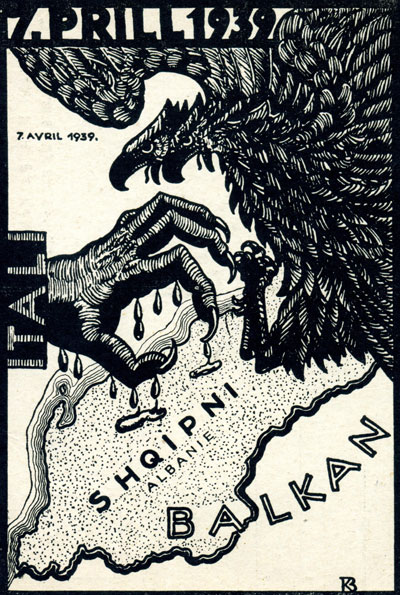

Anti-Italian poster

in occupied Albania

Our first meeting went very well. I immediately discovered him to be reasonable and understanding, though Indelli, who is always an alarmist, had given us the impression that the Yugoslavs were in a state of excitement. Even if this were true of some elements it has not reached responsible quarters. Our conversation touched on the following points:

Albania: acceptance of the fait accompli, including our reasons for sending troops and appreciation of our decision not to send troops in large numbers beyond Durazzo-Tirana to the north. On my part, assurances that we were disinterested in Kossovo.

After my return to Rome I make a report to the Duce, who is quite satisfied. Jacomoni, in accordance with a request from me, has confirmed the agreement for the equality of civil and political rights of Italians and Albanians. The matter is very important, in fact as important as the annexation itself.

APRIL 24, 1939

Starace and Benini on their return from Tirana say they are enthusiastic over all they have seen, and admit that Albania is in a far more satisfactory condition than they had thought.APRIL 26, 1939

We decide on certain important works in Albania, among them the construction of hotels in the larger centres, and for these the Duce gives a person contribution of a million lire.APRIL 30, 1939

I discussed with Alfieri the advisability of accepting the title of Prince of Kruia which the Albanians would like to bestow on me. This would be the first and only thanks received so far for having given Albania to Italy. Nevertheless, my inclination is to refuse it.MAY 9, 1939

Review of troops in the Via del’Impero. The Albanians paraded in Rome for the first time; I confess that this moved me. In the afternoon the sittings of the Roman Curia are resumed; the arrangements are entrusted to the Senate. My father protested against this, recalling that the Senate was the very body which opposed Caesar, and that Caesar was killed between those walls.MAY 12, 1939

There was a bit of a storm in intellectual circles in Albania, which explains why twenty or so persons will immediately be sent to concentration camps. There must not be the least sign of weakness; justice and force must be the characteristics of the new regime. Public works are starting well. The roads are planned in such a way as to lead to the Greek border. This plan was ordered by the Duce, who is thinking more and more of attacking Greece at the first opportunity.MAY 21, 1939

I arrive in Berlin. There are great demonstrations, clearly spontaneous in their warmth. My first discussion with Ribbentrop. […] We have more or less the same discussion with the Führer. He states that he is very well satisfied with the Pact and confirms the fact that Mediterranean policy will be directed by Italy. He takes an interest in Albania and is enthusiastic about our programme for making of Albania a stronghold which will inexorably dominate the Balkans.MAY 25, 1939

A long conference with the Duce. He is increasingly anti-Yugoslav, anti-Greek. We decide to close the Albanian Ministry for Foreign Affairs and to remove foreign diplomats from Tirana. He is thinking also of denouncing the London Pact in consequence of the Anglo-Turkish accord.MAY 26, 1939

Mussolini is taken up with the idea of breaking Yugoslavia to pieces and of annexing the kingdom of Croatia. He thinks the undertaking is sufficiently easy, and, as things stand, I agree with him. Meanwhile, I am thinking of organizing the Albanians of Kossovo better. They could be turned into a dagger pointed at the side of Belgrade.MAY 29, 1939

I made certain general provisions for Albania; among the more important are the unification of the armed forces and suppression of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.JUNE 2, 1939

At the station I received the Albanians, who have come to receive the text of their future constitution which will unify the armed forces and abolish their Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As rewards, we shall give them certain compensations of a personal nature, such as nominations to the Senate, ambassadorial titles, etc. I must say that probably for the first time since the annexation they were visibly satisfied. Which goes to show that personal benefits will frequently silence even the most noble feelings. ...JUNE 3, 1939

Ceremony at the court for the delivery of the constitution to the Albanians. The King asks who drafted the document and observes in a sarcastic tone that there is no heraldic symbol of the dynasty on the Albanian flag. I answer that this is not quite so, because it does have the blue Savoyard sash and the crown of Scanderbeg. This convinces him, but he remains in a bad humour. I report this to the Duce, who seizes the occasion to deliver an attack on the monarchy. Starace is also present. The Duce declares that he is sick and tired of dragging behind him “empty baggage cars, which, moreover, very often have their brakes on”, that the King “is a small man, grumpy and untrustworthy, who at this time is concerned with embroidery on the flag and does not feel any pride in seeing his national territory increased by 30,000 square kilometres”, and that, in conclusion, “it is the monarchy which, by its idiotic chatter, prevents the Army from becoming Fascist. The disgusting Asinari de Bernezzo is responsible for this chatter.”In the afternoon I settled the problem of the co-ordination of the Albanian diplomatic service with the Italian service. A few decorations and a few jobs were enough to accomplish this.

The Operation of emasculating Albania without making the patient scream - the annexation - is now practically completed. As I have already noted, for the first time the Albanians are not depressed. Such is the advantage of cold-blooded and calculated decisions. The Duce and I have brought up the problem of the irredentism of Kossovo and of Ciamuria [Chameria]. The Duce defines this irredentism: “The little light in the tunnel.” That is, the ideal theme for us to play upon in the future to keep the Albanian national spirit high and united.

JUNE 17, 1939

I receive Shtylla, ex-Minister of Albania to Belgrade. I intend to use him in connection with the Kossovo problem, about which he is very well-informed. I shall create an office for irredentisms at the Under-Secretariat for Albania.Bottoni and Benini have just arrived from Tirana, bringing excellent news on the Albanian situation.

JULY 4, 1939

I have received Badoglio’s report on Albania: “Quam parva sapientia!”JULY 22, 1939

I receive Koliegi [Koliqi], with whom I discussed the problem of Kossovo and of Ciamuria. He will prepare a memorandum on our plans. I give these instructions for action in three successive stages: (1) general broad propaganda laying stress on culture and religion; (2) similar propaganda concentrating on direct action; (3) clandestine military organization to be ready for the moment when the inevitable Yugoslav crisis comes to a head.JULY 27, 1939

Good news from Albania, where mining explorations are proceeding very well. The Ammi Company has already yielded 8,000,000 tons of iron ore and many even greater deposits are being discovered.AUGUST 4, 1939

A brief conversation with Christic to call his attention to the danger presented by the excessive liberty of action allowed in Yugoslavia to certain of Zog’s emissaries. According to information in our possession, they are attempting to start frontier incidents. Christic promised he would intervene strongly, and I believe he will keep his word, because he is very much afraid of any possible complications.AUGUST 6, 1939

I received ample assurances from Christic about the precautions that will be taken with reference to the Albanians. I confer with the Duce. The King has expressed his intention of giving me the collar of the Order of the Annunziata. The Duce was evasive at first, since “the collar may lead to compromises that it would be better not to make”, but now he is persuaded as to the desirability of my having it, and to-morrow he is to write to the King about the matter.AUGUST 7, 1939

The Duce has written a fine letter to the King to say that he approves of my receiving the collar of the Order of the Annunziata. He writes among other things: “It is my duty to declare to Your Majesty that to Count Ciano is due that penetration of Albania from within which has permitted us to annex it almost without striking a blow. This in itself is worth the collar.”AUGUST 8, 1939

With Benini at the Duce’s, to discuss the question of Albanian iron ore. The Duce is quite satisfied with the report. He decides that later on I shall make a visit to Albania, during which the collar of the Order of the Annunziata will be conferred on me.AUGUST 19, 1939

I arrive at Tirana, where the news of the conferring of the collar of the Order of the Annunziata reaches me. I inspect public works at Tirana and Durazzo. In Albania much has been done materially and spiritually. Party organizations are excellent, especially work done with the younger people, who are now clearly oriented in favour of Italy.There is no doubt that if we can work in peace, within a few years we shall possess in Albania the richest region of Italy.

I am quite satisfied with what I see, but to-day my spirit is absent. The vicissitudes of European politics are too serious and sad to permit me to concentrate my attention upon Albanian problems only.

AUGUST 20, 1939

On the steamer, the Duke of Abruzzi, I reach Valona. Here, too, the welcome given me was enthusiastic. What misery! Tirana and Durazzo are in contrast two metropolitan centres. And yet the locality is very beautiful, the bay spacious, and the sea rich in fish and fishing facilities. After a few years of work all will be transformed. We were to go to Korcia, but the weather was bad and we put it off. We return to Durazzo. There a telegram from Anfuso reached me to announce that my presence in Rome during the evening was “extremely desirable”. I cancel my visit to Scutari and return to Rome.DECEMBER 19, 1939

A long conference with Albanian Senators. They present their objections and their wishes. Insignificant things of a personal and local character, about which we can give them satisfaction. I am convinced, especially from what they themselves have said, that matters in Albania are moving in a satisfactory manner.DECEMBER 20, 1939

The Albanians take their oath in the Senate.DECEMBER 27, 1939

Verlaci asks for my approval to “. . . take the initiative against King Zog, who, when he is dead, will be less embarrassing than he is to-day”. The matter does not interest us, and I answer that only the Albanians can be the judges of the life of another Albanian.DECEMBER 30, 1939

I bring Verlaci to the Duce. He makes a very optimistic report on the situation in Albania and asks for a greater concentration of powers in the Italian Lieutenancy. Public power must be divided as follows: the government of Tirana is answerable to the Lieutenancy and the Lieutenancy is answerable to Rome. In order to carry out this concentration I have thought of calling Pariani to the position of Inspector-General of the Party in the place of Giro, who has done well during the preparation but who has compromised himself with too many people.Mussolini wants the Albanian plan against King Zog suspended. He gives orders to this effect, and he is right, because we would not derive any advantage from it but only blame.

JANUARY 16, 1940

The carabinieri give the Duce an alarming report on Albania. He takes it very seriously. The carabinieri command is a reliable source of information, but they talk too much, and at times they just pass on observations made by non-commissioned officers. Jacomoni vehemently denies all that the carabinieri report, and prepares, together with Benini, a counter-report. In Albania we are working methodically, and without bluffing, which, in the opinion of some, is perhaps a mistake. But I do not intend to change.

JANUARY 17, 1940

Accompanied by Jacomoni, I discussed the Albanian situation with the Duce. Let the carabinieri think and write as they please. However, one thing is certain: up to now Albania has not caused us the least trouble.JANUARY 18, 1940

I went with Jacomoni to see the Duce. I think the Duce, too, realizes that the alarm created by General Agostinucci, who is called the “stuffed lion” by the Albanians, is, in large measure at least, unjustified. The meeting was useful, at any rate, in that agreement was reached on certain plans for public works, especially in Tirana.JANUARY 30, 1940

Piero Parini points out that the professors and students of Corcia [Korça] who created disorders lately have been identified, and he believes that some harsh punishment is necessary. The Duce approves. I telegraph, ordering that they be arrested and deported to some island in the Tyrrhenian Sea. The Albanian intellectuals, as is logical, are those who most oppose the new situation, and it is necessary to absorb them wherever possible, or to deal severely with those who are unwilling to be convinced. It is not a very serious problem: a matter involving two or three hundred persons. The Albanian people do not give trouble. They work, earn, and enjoy a comfortable life, which they have not had until now, and most of them are satisfied.APRIL 7, 1940

A year has passed since we landed in Albania. This is a day that I remember with emotion. And, talking about Albania, General Favagrossa to-day refused the minimum financial subvention needed to solve the housing problem in Albania. With the best will in the world he can’t give any money because he hasn’t got it. With him I made a rapid survey of the situation with regard to our metal reserves. The results were very sad. Italy is losing all her foreign markets, and even the small amount of gold that we have to spend cannot be converted into the metals that we need.MAY 21, 1940

The King is nervous. This morning I went to the royal palace to accompany the Albanian mission, which has come to bring the Address in Reply to the Speech of the Crown. The King almost attacked me on the question of the collar of the Annunziata for Goering. He said: “This thing has gone all wrong. To give Goering the collar is a gesture that displeases me, and to send him a telegram is distasteful for a hundred thousand reasons.” On the military situation His Majesty expressed himself as being unfavourable to the Germans.MAY 22, 1940

I leave for Albania. I arrive at Durazzo and Tirana. A very warm welcome. The Albanians are far on the path of intervention. They want Kossovo and Ciamuria. It is easy for us to increase our popularity by becoming champions of Albanian nationalism.MAY 23, 1940

I visit Scutari and Rubico [Rubig]. A very promising copper mine. The public works that I visited this morning are also satisfactory. Everywhere a warm welcome. There is no question but that the mass of the people is now won over by Italy. The Albanian people are grateful to us for having taught them to eat twice a day, for this rarely happened before. Even in the physical appearance of the people greater well-being can be noted.

Market scene

in central Albania

(Photo: Karl Wimmer, 1944)MAY 24, 1940

I mingled with the workers at Ragosina [Rrogozhina]. Italian labourers mix well with the Albanians. We find the greatest difficulties in the Italian middle classes, who treat the natives badly and who have a colonial mentality. Unfortunately, this is also true of military officers, and, according to Jacomoni, especially of their wives.MAY 25, 1940

Stopped at Butrinto [Butrint]. Very beautiful. The Canal of Corfu. Port Edda [Saranda]. I returned to Italy.AUGUST 10, 1940

I talked to the Duce about the difficulties that have arisen on the Greek-Albanian frontier. I don’t wish to dramatize the situation, but the Greek attitude is very tricky. The Duce is considering an “act of force, because since 1923 he has some accounts to settle, and the Greeks deceive themselves if they think that he has forgotten”.AUGUST 11, 1940

Mussolini still speaks of the Greek question and wants particulars on Ciamuria. He has prepared a Stefani dispatch, which will start agitation on the question. He has called Jacomoni and Visconti Prasca to Rome, and intends to confer with them. He speaks of a surprise attack against Greece towards the end of September. If he has decided on this, I feel that he must work fast. It is dangerous to give the Greeks time to prepare.AUGUST 12, 1940

I accompany Jacomoni and Visconti Prasca to the Duce, who sets down the political and military lines for action against Greece. If Ciamuria and Corfu are yielded without striking a blow, we shall not ask for anything more. If, on the other hand, any resistance is attempted, we shall go the limit. Jacomoni and Visconti Prasca consider the action possible, and even easy, provided, however, that it be undertaken at once. On the other hand, the Duce is still of the opinion, for general military reasons, that the action should be postponed until towards the end of September.OCTOBER 14, 1940

Mussolini speaks to me again about our action in Greece, and fixes the date for October 26th. Jacomoni gives very satisfactory information, especially on the state of mind of the population of Ciamuria, which is favourable to us.OCTOBER 15, 1940

A meeting with the Duce at the Palazzo Venezia, to discuss the Greek enterprise. Badoglio, Roatta, Soddu, Jacomoni, Visconti Prasca, and myself take part in it. The discussion is available in a stenographic report.Afterwards, at the Palazzo Chigi, I speak with Ranza and Visconti Prasca, who explain their military plans. I speak also with Jacomoni, who gives an account of the political situation. He says that in Albania the attack on Greece is awaited keenly and enthusiastically. Albanian youth, which has always been reserved in its attitude towards us, now makes open manifestations of approval.

OCTOBER 17, 1940

The Duce is at Terni. Marshal Badoglio comes to see me, and speaks very seriously about our action in Greece. The three heads of the General Staff have unanimously pronounced themselves against it. The present forces are insufficient, and the Navy does not feel that it can carry out a landing at Prevesa because the water is too shallow. All of Badoglio’s talk has a pessimistic tinge. He foresees the prolongation of the war, and with it the exhaustion of our already meagre resources. I listen, and do not argue. I insist that, from a political point of view, the moment is good. Greece is isolated. Turkey will not move. Neither will Yugoslavia. If the Bulgarians enter the war it will be on our side. From the military point of view I express no opinion. Badoglio must, without any hesitation, repeat to Mussolini what he has told me.OCTOBER 18, 1940

I go early to see the Duce. I find Soddu in the ante-room. He has spoken with Badoglio, who declared that if we move against Greece he will resign. I report to the Duce, who is already in a very bad humour because of Graziani. He has a violent outburst of rage, and says that he will go personally to Greece “to witness the incredible shame of Italians who are afraid of the Greeks”.OCTOBER 27, 1940

Numerous incidents in Albania. Action is expected at any moment. And yet the four diplomats, German, Japanese, Spanish, and Hungarian, to whom I handed the text of the ultimatum to Greece, were rather surprised.OCTOBER 28, 1940

We attack in Albania and confer in Florence. In both places things have gone well. Notwithstanding the bad weather, the troops are moving fast, even if air support is lacking.OCTOBER 29, 1940

The weather is bad, but the advance continues. Diplomatic reactions in the Balkans are quite limited for the time being. No one makes a move to defend the Greeks. It is now a question of speed, and we must act quickly. I leave for Tirana during the evening.OCTOBER 30, 1940

At Tirana. Bad weather. I do not fly. I inspect the public works, the roads, the port. Things are going a little slowly. It’s because of the rain.OCTOBER 31, 1940

Continued bad weather. I write a long letter to the Duce. Here they complain of the ill-will of the General Staff, which has not done what it should have done to prepare for the action. Badoglio was convinced that the Greek question could have been settled at the peace table, and his attitude was affected by this prejudice. This has resulted in much weaker preparations than we were led to expect.NOVEMBER 6, 1940

Mussolini is dissatisfied over the way things are going in Greece. The attack on Corcia did take place, even though the results were not those bragged about by the British radio. The enemy has made some progress and it is a fact that on the eighth day of operations the initiative is in their hands. Soddu has left for Albania and will assume command. Visconti will remain in command of the Army of the Epirus.I don’t think that we have come to the point where we must bandage our heads, although many are beginning to think so. As a matter of fact, in the evening Mussolini is calmer. The forces now concentrated in the Corcia sector indicate that the Greek push may be definitely slowed up. Afterwards the counter-attack and success will come. Perhaps even much sooner than is expected.

NOVEMBER 7, 1940

I confer with Benini, who has just returned from Tirana, and accompany him to the Duce, to whom he makes a long report. On the Corcia sector our collapse began when a frightened battalion of Albanians ran away. It seems there was no treachery. Our soldiers did miracles. Entire Greek divisions were stopped by the resistance put up by platoons of customs guards, and the Greeks did not pass until the defenders had died to the last man. We withdrew to a defensive line. Soddu maintains that the arrival of a few regiments of Alpine troops would definitely eliminate all dangers. On the Epirus sector Visconti is still relatively optimistic and thinks that we can place ourselves in a position to bring about the fall of Jianina [Janina]. Soddu is not of this opinion and thinks we ought to drop this manoeuvre, augment our forces, and repeat our attack.The civilian organization is excellent. The port of Durazzo is operating at full capacity, but is not too crowded with ships. So also are the roads, which ensure a continuous and safe flow of traffic between the front and the rear.

NOVEMBER 8, 1940

The news given by Jacomoni does not coincide with that from headquarters, which is more pessimistic. The Duce has a long conversation with Badoglio and Roatta, and makes plans for the dispatch of troops. It appears that Badoglio is lugubrious, and this irritates the Duce. He is especially irritated because Badoglio asks for four months more. Too long. We must act immediately and energetically. The Greek attack is slowing down, and they have no reserves. Grazzi, returning from Athens, confirms that the internal conditions of the country are very bad, and that their resistance is made of soap bubbles. According to him, Metaxas, receiving our ultimatum in his night-shirt and dressing-gown, was ready to yield. He became unyielding only after having talked with the King, and after the intervention of the British Minister. In the evening news is better. The Greek attack is weakening on all sectors.NOVEMBER 9, 1940

The situation is stationary on the Albanian front. The Greek attack has lost its impetus and is dying out. But we, too, unfortunately, have not the strength to resume our advance. We shall do so in a few weeks. The Duce is now very angry with Jacomoni and Visconti, who had represented the operation as too easy and sure of success.NOVEMBER 10, 1940

An offensive thrust by our cavalry in the vicinity of Prevesa made good progress and met with no resistance, which proves that the Greeks are only holding a weak line and that having broken this we shall go on with ease. If we had two divisions in Albania to-day we could launch them with certainty of success.From Albania we receive news that the situation is re-established. Had we had more adequate forces we could have gone far. Now we can only wait. Unfortunately, success, when it does come, will no longer be of the first magnitude.

In the evening the news from Albania is more serious. Pressure continues, and resistance is more difficult. And then we lack guns, while the Greek artillery is modern and well handled.

NOVEMBER 12, 1940

The British bombardment also did serious damage to Durazzo. The Agio oil refinery is burning. Fortunately the port is intact. It is very important to keep it from being damaged, since it is our only access to Albania. It has worked well and is still working splendidly. No slowing down or bottleneck in this port.NOVEMBER 15, 1940

It seems that the Greeks have resumed their attack all long the front, and with considerable forces. Up to now we have resisted very well. This is also confirmed by a letter from Starace, which, with all its realism, is not pessimistic. Above all, he blames Visconti Prasca, who had too lightly asserted that everything was ready to the last detail, when, as a matter of fact, the organization of our forces was altogether defective.In the evening the news from Albania is more serious. Pressure continues, and resistance is more difficult. And then we lack guns, while the Greek artillery is modern and well handled.

NOVEMBER 16, 1940

We are putting up a strong resistance in Albania.NOVEMBER 17, 1940

I leave for Salzburg. News from Albania is uncertain; an eventual withdrawal is not to be excluded.NOVEMBER 18, 1940

Alternating news of defeats and victories on the Albanian front. I fear that we shall have to withdraw to a pre-established line. The loss of Corcia is certainly not the loss of Paris, but it will serve to give a name to the battle and help the enemy to beat the drums of propaganda against Italy. This is why I hope that we may hold on to Corcia.NOVEMBER 21, 1940

I find the Duce calm, decided, not worried. What is happening in Albania saddens but does not disturb him. He is critical of our military men, of Badoglio, and announces imminent changes in the army command.During the evening Soddu announces that he intends to abandon Corcia and withdraw on the entire front. And yet the Greek pressure seems to be less. Mussolini intervenes to get him to reconsider, but the machine is in motion and it cannot be stopped now.

NOVEMBER 22, 1940

Pavolini recounts confidentially that Badoglio said to him: “There is no doubt that Jacomoni and Visconti Prasca have a large share of the responsibility in the Albanian affair, but the real blame must be sought elsewhere. It lies entirely with the Duce’s command.NOVEMBER 23, 1940

News from Albania is of an orderly retreat without pressure from the enemy.NOVEMBER 25, 1940

Soddu confirms the better news from Albania. He considers that the forces under him are sufficient to guarantee a stabilization of the line.NOVEMBER 27, 1940

From Albania the news from Soddu indicates progressive improvement. News from Starace on the other hand, is not very optimistic, since he still feels that our fate is hanging by a thread.NOVEMBER 28, 1940

Bad news from Albania. Greek pressure continues, but above all our resistance is growing weak. If the Greeks had strength enough to penetrate our lines we might yet have a great deal of trouble.NOVEMBER 29, 1940

Starace, who has just come from Albania, sees things in pretty dark colours, and passes severe judgment on the behaviour of our troops. Our soldiers have fought but little, and badly. This is the real, fundamental cause of all that has happened.NOVEMBER 30, 1940

Meeting of the Council of Ministers. The Duce talks at length about the situation. He reads the principal documents and, while personally assuming responsibility of the political decisions, he directs some hard blows at Badoglio as regards military action. The Duce’s thesis is this: Badoglio was not only in agreement, but even over-enthusiastic. The political side of the question was handled perfectly; the military action was entirely inadequate. He did not conceal the gravity of the situation, that is the imminent retreat to the south and the enemy’s attack now going on in the Pogradec zone. “The situation is serious,” said the Duce. “It might even become tragic.” In the Council of Ministers there was a genuine revulsion against de Vecchi when the Duce mentioned his name and read the telegrams in which he had spurred him on to the attack on Greece. The Duce called in General Cavallero, and this indicates his intentions. Cavallero is an optimist who does not believe in the possibility of a defeat in Albania, having full faith in our ability to take the offensive once more. I record everything but guarantee nothing. I am becoming more and more cautious in military matters.DECEMBER 1, 1940

News from Albania has improved. We are holding and even counter-attacking in the north, while in the south the withdrawal continues without enemy pressure.DECEMBER 3, 1940

Greek pressure has started again on the Albanian front, and it seems that the 11th Army must now make that withdrawal from Argirocastro [Gjirokastra] and Port Edda which we had hoped to avoid.DECEMBER 4, 1940

Sorice telephones at an early hour that we have lost Pogradec and that the Greeks have broken through our lines. Then he informs us that Soddu now thinks that “any military action has become impossible and the situation must be settled through political intervention”. Mussolini calls me to the Palazzo Venezia. I find him discouraged as never before. He says: “There is nothing else to do. This is grotesque and absurd, but it is a fact. We have to ask for a truce through Hitler.” This is impossible. The Greeks will, as a first condition, ask for the Führer’s personal guarantee that nothing will ever be done against them again. I would rather put a bullet through my head than telephone Ribbentrop. Is it possible that we are defeated? May it not be that the commander has laid down his arms before his men? I am in no position to give military suggestions, but rigorous logic tells me that if a rout has not already started it is still possible to form a bridgehead at Valona and, with fresh forces, a safety line on the river Skumbini [Shkumbin] What counts now is to resist, and to stick to Albania. Time will bring victory, but if we give up it is the end. […]The idea strikes me that I can perhaps verify the situation through Jacomoni, and I telephone to him. I immediately get the impression that in Tirana they are more at ease than in Rome. I fear that some misunderstanding lurks in the air. In fact, Jacomoni says that “as a political solution, Soddu had intended a military diversion on the Greek flank, such as would be produced by a German or Yugoslav intervention”. News from the High Command also improved during the day, and Soddu and Cavallero leave for Elbasan to study the situation on the spot.

DECEMBER 5, 1940

News from Albania indicates that the situation is unchanged. The time gained is entirely in our favour, the more so since the Germans have given us fifty transport planes. In this way traffic is facilitated.

DECEMBER 6, 1940

News from Albania unchanged.DECEMBER 15, 1940

In Albania also there was a retreat, which Cavallero considers not to be serious and of purely strategic value to the enemy. He believes that his reserves are sufficient to stop the break-through.DECEMBER 17, 1940

Again a bad withdrawal in Albania towards Clisura [Këlcyra] and Tepeleni [Tepelena]. The Duce has prepared a letter, a harsh letter, to Cavallero, with an order to the troops to die at their posts. “More than an order from me,” he wrote, “it is an order from our country.” Let us hope that this lash will have its effect.DECEMBER 18, 1940

I confer at length with Cavallero, who has returned from Albania. He is distinctly optimistic. He not only thinks that a notable surprise is possible, but he also believes that the critical phase is almost over, and he is planning to strike the first offensive blow at Clisura the day after to-morrow. This is to be followed by another in the Tomorrizza [Tomorica] Valley. He thinks that by February 1st he will have completed preparations for an offensive that should bring us to Corcia; from there on he will press the offensive as rapidly as possible. Being in this mood, he attaches little importance to the vicissitudes that our lines have suffered in the last few days.DECEMBER 19, 1940

I cannot say that what has happened has proved Cavallero right. The Siena division, which was covering the coastal area, was broken to pieces by a Greek attack. The position is dangerous. Once they enter the valley of Sciuscizza [Shushica] the march on Valona is easy and natural, and it is not difficult to see how heavy a loss the fall of Valona would be.DECEMBER 22, 1940

Cavallero, who is the type of man who always sounds the optimistic note, says that the counter-attack on the coast line will be mounted to-morrow or the day after. We do not expect great results, but hope to lessen pressure on Valona. This would be a success, because Valona represents a strategic objective of the first order for the Greeks and the English, and also because we shall recover the initiative.DECEMBER 23, 1940

Nothing new, but I find the Duce rather irritated over Saturday’s withdrawal, contrary to the expectations of Cavallero. Instead of lessening, the pressure on Valona is now increasing. The Duce no longer believes what Cavallero says.DECEMBER 25, 1940

Christmas. The Duce is sombre, and speaks again about the situation in Albania. He appears more tired than usual, and this saddens me very much. The Duce’s energy at this time is our greatest resource. He no longer believes in Cavallero. He says that his optimism is like that of one whistling in the dark. In fact, Cavallero reports from Tirana that “the height of the crisis has been passed, and now there is a complete change of spirit in the troops.”DECEMBER 27, 1940

The usual story in Albania, and this displeases the Duce. He is right. Notwithstanding Cavallero’s bright words one cannot read the situation clearly. He promises this offensive of the valley of Sciuscizza, but it does not take place, and we would not be surprised if once again the Greeks should launch theirs first.DECEMBER 30, 1940

During my absence the Duce conferred the command of the armed forces on Cavallero, and took it away from Soddu. For some time he had been dissatisfied with Soddu’s temperamental changes of humour. One day all rosy, and another all black. The final blow came when the Duce learned that Soddu, even in Albania, was devoting his evening hours to composing music for the films.JANUARY 11, 1941

Yesterday evening’s news of the air and sea battle was perhaps exaggerated. We cannot as yet establish whether the British carrier has been sunk or not. On the other hand, from Cavallero we are not getting very good news on the course of affairs in Albania. Clisura is lost. In itself this means nothing. It is a mass of huts in a more or less dilapidated condition, but it is a name, and Anglo-Greek propaganda is already sounding all the trumpets of the press and radio. It also proves that the wall of resistance, that famous wall which we have been awaiting for seventy days, has not yet been formed. Our troops, even the fresh ones, hold out until Greek pressure starts, but they yield ground rapidly under attack. Why? Mussolini finds that the entire situation is an inexplicable drama, so much the more serious because it is inexplicable. Cavallero, with whom I have spoken by telephone, does not hide the gravity of what has happened, but he does not feel that the situation at Berat, and therefore at Valona, has been compromised. He continues to speak of the famous attack along the coast, but of this, however, we see no concrete evidence.JANUARY 13, 1941

To-morrow morning Mussolini is going to Foggia to meet the generals from Albania. He considers the moment has come to make some decision, especially because Guzzoni is very insistent that the offensive should take place along the coast. He thinks that this will have the effect of exploding the Greek plans for an offensive and even of bringing us back to the old frontier.JANUARY 16, 1941

On the Clisura front another Greek attack takes place. Let’s hope that our troops will hold.JANUARY 18, 1941

Departure for Salzburg. Mussolini arrives at the train frowning and uneasy. He is shaken by the news from Albania. Nothing too dramatic, but once again we have had a kick in the pants, leaving many prisoners in the hands of the enemy. The serious thing is that it involves the Lupi di Toscana, a division which had an excellent reputation and a grand tradition, which landed only a short while ago in Albania, and on which he had placed high hopes.JANUARY 22, 1941