| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

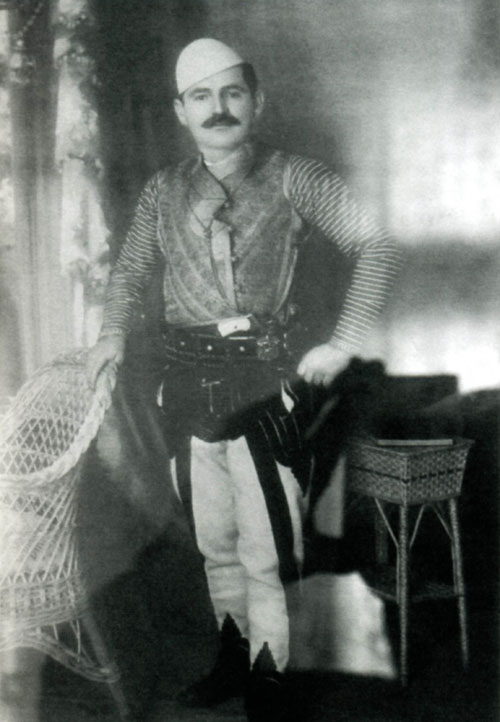

Lt. Col. Stirling (1880-1958).

1953

W. F. Stirling:

A British Officer in Albania,

1923-1931British military figure, Lieutenant-Colonel Walter Francis Stirling (1880-1958), known as Michael Stirling, was born in Portsmouth and spent his youth at Hampton Court Palace. He trained at Kelly College and the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. During the First World War, he was chief staff officer to Lawrence of Arabia and became somewhat of an expert in Arab affairs. In 1923, he was contacted by the British consul in Albania, Sir Harry Eyres, about a position to advise and assist in the reorganization of the Albanian Ministry of the Interior. Stirling accepted the post and arrived in Albania in May 1923. He worked as inspector general of the new Albanian gendarmerie but he was not a popular figure. He quarrelled with the instructors he had hastily recruited, had poor relations with dictator Ahmet Zogu and was heartily disliked by the British legation there. Stirling was finally removed from his post by Zogu in August 1926 and replaced by Sir Jocelyn Percy. To keep him in the wings, so to speak, Zogu made him inspector general of civil administration, a rather nebulous position he retained until 1931. His book “Safety Last” (London 1953), contains the following chapter on his experience in Albania.

I was thinking about what I should do after my dismissal from Jaffa, when our Minister in Albania suddenly wrote to me saying that the Albanian Government was seeking an experienced British official to reorganise the Ministry of the Interior. My name had apparently been suggested to him by a well-known judge in the Sudan who was nicknamed Abu saba saneen, or “the-father-of-seven-years,” from his practice of never giving a sentence of shorter duration. It was pointed out that the post, though somewhat hazardous and carrying a salary of only £1,000 a year, was nevertheless thought to offer plenty of scope to the right man.

I accepted it at once, and in May 1923 embarked for Durazzo, accompanied by my wife, our baby daughter Elspeth (born in Jaffa the previous summer), her nurse, and three dogs. The master did me the honour of dressing ship from stem to stern and I was followed on board by a great concourse both of Jews and Arabs who seemed really sorry to see me go. In my pocket I also had telegrams of appreciation from the Bishop in Jerusalem and from the Patriarch of the Greek Orthodox Church.

Corfu is a very lovely island and still permeated with the influence of its one-time British ownership. The better-class houses are constructed in the Georgian or Regency manner, and the fanlights over the doors are often identical with those that can be seen in Bruton Street. Cricket was played with enthusiasm, and materials were still being sold by the yard.

On our arrival at Durazzo we stayed a few days with the British Consul and then moved to a small house in Tirana, the capital.

Before going farther, it would be as well to give some historical account of Albania.

The Albanians are a distinct race. Neither in their physical make-up nor in their language does there seem to be any affinity to other European peoples. One theory is that they, and perhaps the Basques in the Pyrenees, are the only people remaining of the original population of Europe; a population which was engulfed and absorbed at a time when there was a great migration from the East, and when one of the migrating tribes settled in Greece and became the people we know as the ancient Greeks. Neither they nor the Basques were absorbed by the newcomers because they lived in pockets of the high mountains. In the earliest records they seem to have been known as Illyrians.

In the days of the Romans they had become an important Roman province and the main gateway to the East, since the Via Ignatia started from the port of Durazzo. To this day their language contains many Latin roots and forms. Little is known of the history of Albania in medieval times but, at the end of the Crusades, she was broken into small Principalities under Norman barons. Later she became the fief of Venice, but achieved independence under their national hero, Skanderbeg. He fought the Venetians and he fought the Turks, and succeeded in keeping his people from all outside oppression. At his death the Turks overran the country, which became a Turkish Province for something like four hundred years. Hence their Arabic and Turkish words, but their basic language remains unique.

On the rise to power of the Young Turk Party in Turkey, the Albanians revolted and formed themselves into an independent State. This worried the Chancelleries of Europe and it was thought wise, as some measure of control, to provide the young State with a nominated Prince.

Jealousies broke out and every suitable candidate was objected to by one or other of the nominating Powers. The result was that a feeble German princeling was eventually chosen as being harmless. This was Prince Wilhelm of Wied. It was true he was a poor creature, but they had overlooked his wife, who was a woman of great character and very intelligent.

His reign was short and unhappy, since before very long he was besieged in Durazzo by his own War Minister. On the outbreak of the first European War, Prince Wied fled the country and Albania was occupied by the Austrians in the north, by the Italians in the south-west and by the French in the south-east. So during the period of the war she passed out of existence.

However, when the occupying troops, with the exception of the Italians, were withdrawn, the Albanian Parliament met and formed their own Government once again. To meet the vacuum in the Constitution caused by the defection of their ruling Prince they elected four Regents to exercise his powers. There were two Moslem Regents, one Orthodox and one Catholic–this being in proportion to the creeds prevalent in the country.

Having formed, or re-formed, their Government, the next step was to attack the Italian forces yet remaining in the country. The Italians, being at the time rotten with Communism, put up a very poor defence and were literally driven into the sea at Valona, retaining only the little island of Sassena which lies across the entrance to the Gulf of Valona.

Such was the Government under which I had now taken service. The Minister of the Interior was Ahmed Bey Zogu who, later on, was to become King Zog.

Ahmed Bey was an exceedingly able and intelligent man and was the hereditary chief of the Mati tribe. In the second Balkan War, when Albania was still a Turkish Province, the Turks had ordered the Mati tribe out to fight. They refused, as they said that they never fought except under the leadership of their own chief. Ahmed was then a boy at school in Constantinople. So the Turks took him out of his school and sent him back to his tribe, which he most successfully led throughout the campaign.

The chieftainship had descended to him from father to son from the sixteenth century, and so he was of no upstart breed.

During the initial discussions I had with the Albanian Government on my arrival at Tirana, I refused to make any recommendations as to the reorganisation of the Ministry until I had toured the whole country and seen how the internal administration functioned. I was therefore given a secretary-interpreter with whom I set off on two long tours, first to Scutari and the northern mountains, then to Korça and the southern regions. After visiting all the principal districts I returned to Tirana to think things over. I saw quite clearly what ought to be done, but not so clearly what it was possible to do.

The country was divided into prefectures, each controlled by a prefect who was immediately responsible to the Ministry, but the selection of suitable officials for these posts was for various reasons a serious problem. In the first place, the country was also divided racially between the Ghegs in the north and the Tosks in the south. The former were tall, lean mountaineers, silent, dour and dignified; the latter were small men, gay, laughing and fat. As a fighting race, the Ghegs looked down on the Tosks, and so it was difficult for a Tosk prefect to rule in a Gheg prefecture. Secondly, there were the religious differences. The north was mostly Catholic, the centre Moslem, and the south Greek Orthodox, the proportions being roughly 1:3:1. Thirdly, there were the differences between the plainsmen of the coast and the mountaineers, and finally, the difference between those who were considered besnik, or loyal to the Government, and those who were not.

With all these factors to be taken into consideration it was by no means easy to find the man for the job, and each successive Government had to be balanced in relation to these various factors. In drawing up lists for the portfolios to be held in a new Cabinet, as I so often did in later years, my main difficulty was that after selecting the best men for the various ministries I would then discover that there were too many Catholics in the Cabinet or, perhaps, too many Tosks, and the different posts and candidates would have to be re-shuffled once again.

Tirana was then a mere village set in a cup in the foothills of the great mountains. The houses were grey and cream-coloured with red tiled roofs, each in its own garden and embowered with trees. Here and there the minarets of mosques pierced the skies, and towering over all were the white-capped mountains. The capital was about twenty-five miles from the port of Durazzo, which was the seat of the British and Italian legations.

It was not long before I came up against the members of our legation. They expected me to send them a copy of all my reports to the Albanian Government. I refused to do this, since I was paid by the Albanian Government and therefore considered my reports to be Government property, but agreed to warn our legation should any action by the Albanian Government appear to me to be inimical to British interests.

The shooting in Albania was really excellent, and our Minister, Sir Harry Eyres, was an extremely keen shot. One very cold day when I was out with him in the marshes round Durazzo the birds were so plentiful that he would not stop even for a sandwich lunch. It was so icy that the sea was frozen seven yards from the beach, and my hands were so numb that for the last hour I could hardly pull the trigger. When we got back to the legation the old man looked at his watch and exclaimed:

“Humph! Too late for tea–spoil your dinner.”

But dinner itself was not much to look forward to. The Minister did not keep a cook but used to get his food sent in from a local restaurant, and for reasons of economy ordered three portions for four people. When three small fish arrived for four ravenous men a fair division of the feast was difficult to achieve.

In the summer of 1924 an agrarian revolt broke out and Ahmed Bey Zogu, the Minister of the Interior, had to flee the country. The revolt was headed by a certain Orthodox bishop, Fan Noli. He was a Harvard-educated intellectual and quite a good musician; he had once played the organ in a cinema in the United States. At the time of the revolt I was on leave in England, and when news of it filtered through I assumed rather despondently that my job was at an end. However, the bishop sent me a telegram asking me to return as soon as possible.

When I got back I found an entirely new set of ministers in power, all amateurs, though some of them were clearly anxious to improve conditions in the country. The only stumbling-block was Fan Noli himself. He was the most cynical man I have ever met. He once said to me that he supposed he ought to keep at least one of the many promises he had made on seizing power. I don’t think he ever did so.

Albanian tribesman of the Shala

mountains (Photo: W. F. Stirling).

His position in the country was undoubtedly supported by Communist funds, and very soon a Soviet Minister arrived in Albania, complete with a staff considerably larger than that of any other legation. The Powers promptly made combined representations to the Government, stating that the new legation would not be tolerated, and within three days the Russian Minister and his staff had packed up and left.

At the end of the year Ahmed Bey Zogu staged a comeback and, with the help of the Jugoslavs and some fifteen thousand Albanian mountaineers, invaded Albania with the intention of turning out the Soviet-sponsored bishop. By Christmas Eve he had penetrated the principal mountain chain and was reported to be just east of the great range that protected the capital. There were no more than two passes over this range, and these could only be crossed by a column in single file. Meanwhile the Government troops held all the summits, their machine-guns dug in and sited to cover the tracks of approach.

The firing, though distant, seemed to be pretty heavy, and after lunch my wife and I started out for some high ground south of Tirana hoping to see something of the fighting. I had only one pony available at the time, so she rode while I walked, but when we came to a stream I vaulted up behind the saddle, for I hate getting my feet wet. The pony did not approve of this and in mid-stream started to buck. I clung on to my wife’s shoulders, but we both came off and disappeared gracefully beneath the water. Luckily it was not very deep and we rose to the surface bursting with laughter, much to the surprise of some peasants who were watching nearby.

There was nothing to be seen of the fighting except a few bursts of shrapnel over the mountain tops, which indicated that Ahmed Bey Zogu had a mule battery with him, so we returned home; but after tea I heard the sound of the firing suddenly change. A rifle fired straight at one, however far away, has a quite distinct sound, and I knew at once that Ahmed must have forced the passes. I walked down to the main square of the town and chatted to some of the ministers whom I found in a cafe. I asked them about the situation and they replied that Ahmed Bey Zogu could beat his head against the Government positions for as long as he liked; he would never get through. I smiled to myself, for I knew very well he was through already.

Two hours later a messenger arrived, with his horse in a lather, and shouted that all was lost; the Government troops were in full retreat. Within half an hour there was not a penny left in the Treasury nor a minister in the capital. They were all streaking off for Durazzo in the hopes of escaping to Italy. Luckily for some of them the Italian fishing-fleet was in harbour and, after much bargaining, the officials were taken off at a price of eighty gold sovereigns a head. It was the most profitable fishing venture the Italians had ever had.

Tirana was in a whirl of excitement and joy as the mountaineers came streaming in. All the inhabitants seemed to be firing their rifles into the air, the bullets came raining down from the sky. We happened to be giving a small dinner-party that night, and our guests were somewhat perturbed to find themselves racing up the garden path while bullets plopped down through the leaves of surrounding fig trees.

Ahmed Bey Zogu entered the capital with about fifteen thousand of the wildest of wild mountaineers, some of whom had never before seen a town. They had been fighting through the mountains for three weeks, and it says a great deal for Ahmed’s control over his men that not a shop was rifled nor even a fruit stall robbed.

The streets next morning were a wonderful sight, with the mountaineers strolling about in their colourful dress. They wore hopenkos, or rawhide sandals, trousers of stiff white felt, a coloured sash stuck full with daggers and pistols, a coarse cotton shirt with full sleeves caught in at the wrists, a magnificent short bolero heavily embroidered with gold lace, and a round, brimless pill-box hat of white felt. Every man carried a rifle in addition to the minor armament round his waist.

As a result of the revolution it was realised that the existing system, whereby four old gentlemen acted as Regents, was cumbersome and unworkable, for the four of them together could not exert the power which the head of a State should possess. Consequently it was decided to establish a republican form of government, and a deputation came and asked me to draw up a constitution, more on the lines of the American than the French, since it was desirable for greater powers to be vested in the president. Since I knew nothing whatever about the complicated American Constitution, I suggested that they approach the American Minister. They were reluctant to do this and asked me to lend them some books on the subject. The best I could offer was a Whitakers Almanack, which defines the powers of the President and the Judiciary and the relations of the Houses, and from this a commission of Albanian lawyers eventually drew up a workable constitution for the State.

Ahmed Bey Zogu was named first President of the Albanian Republic. An extremely intelligent man, he started off with the very best intentions and schemes for the reform of the country’s administration and the well-being of the people. He realised that the first essential was to establish security in the country and that for this purpose a really first-class gendarmerie force was needed. He therefore commissioned me to go to England and engage a group of British officers who would form a British inspectorate for his gendarmerie.

When I got to London I thought I should inform the British Government of Ahmed Bey’s proposals and so called on Sir Eyre Crowe, the permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. He listened carefully to what I had to say and then advised me to put it down on paper for the information of Sir Austen Chamberlain, the Secretary of State. I wrote a concise report on the situation in Albania, on the necessity for a highly trained gendarmerie, on the importance for the peace of the Balkans of a firm Albanian Government, on the various factors affecting the selection of officers from other nations for this work; and I finally remarked that I did not believe His Majesty’s Government would allow a nucleus of German staff officers to be established in the heart of the Balkans, which would be the only alternative if my request for the employment of British officers was refused.

Sir Austen wrote in reply that while he could not actually prevent me from engaging these officers, I would do so at my own peril. He added that he was requesting the War Office to forbid any serving soldier to join me, and told me that I was to inform any officer I engaged that he could expect no protection or support from the British Government. The wording of the letter and the foolishness of the decision annoyed me so much that I proceeded straightway with the enrolment of the officers I required. With the help of various officers’ associations I interviewed a number of candidates and selected ten who had good war records and who seemed to be well recommended.

I then returned to the Foreign Office and told Sir Eyre Crowe what I had done. He, I may say, was completely on my side. “This may interest you,” he said, flipping a telegram across the table. It was a personal message from Mussolini to Sir Austen, thanking him for his courtesy in telegraphing in full the terms of his letter to Colonel Stirling with respect to the inauguration of a British inspectorate of gendarmerie in Albania. I was amazed that a Minister of the Crown should so far demean himself as to explain to the head of a State like Italy the manner in which he had dealt with one of His Majesty’s subjects. My next reaction was one of amusement, for Mussolini himself must have been laughing up his sleeve. Sir Austen was probably acting on the well-known adage “once a soldier, always a fool,” for he had never even sent for me or questioned me personally. Had he done so, I could have told him that I had already discussed the matter with Mussolini when I had gone to see him in Rome on my way to London, and after pointing out to the Duce the advantages to Italy of having a friendly British influence in Albania, I had won his consent and support for the scheme.

Sir Austen’s attitude was due, I believe, to the fact that the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was about to prospect for oil in Southern Albania, and he was fearful of arousing any sort of antagonism on the part of the Italian Government. The officers who thus took service with me were each and severally warned that they could expect no help or protection from the British Government if they got into trouble, and that they would come under and be amenable to Albanian law.

I had had only ten days in which to choose these officers and check their circumstances. They were mostly colonels, majors and captains and some of them had been awarded the C.M.G. or the D.S.O. among other distinctions. Nevertheless I was obliged to return two or three of them to England very soon, for although they were men with good war records, they had rapidly deteriorated in the post-war years and were no longer suitable for an active life, either on account of drunkenness or addiction to drugs.

Albania was ill-provided with roads and only the main towns, such as Scutari, Durazzo, Berat, Elbasan, Valona and Korça, were linked together. The other communications were little more than mule tracks, along which one stepped into a country and breathed an atmosphere at least four centuries older than the rest of Europe. Even in the days of the Turks the law of the Government did not apply in the mountains. In Scutari, for instance, although a whole Turkish division was garrisoned there, it was not safe for a Turk to ride more than three miles beyond the city walls. Since the Turkish Government had no power to enforce law and order in the mountains, the mountaineers had evolved a law of their own known as the Lex Dukajini, or the law of Duke John. Expounded and laid down by a Norman baron in the fourteenth century, it follows in some respects the law of England as it is today; whereby all trials are by jury and judgment is given according to precedent.

Gendarmerie post in

the Mat region.An interesting aspect of the Lex, which is probably unique, provides that a woman can legally become a man, and I have come across half a dozen such cases. The transition may occur for a variety of reasons. If, for instance, all the sons of a family are killed, the eldest daughter might apply to the tribal council for the right to be regarded as a man. Or again, if a girl, betrothed at an early age, finds when she grows up that she does not want to marry her fiancé, she cannot refuse to marry him–for a refusal would be regarded as an insult to his family and would start an immediate blood feud–but she can apply to the council of the tribe for permission to become a man. If this is agreed, she doffs her skirt, wears trousers, carries a rifle and does no more work–for no man in Albania is expected to work, seeing that he has to carry and use a rifle at any hour. There is, however, one small snag in this arrangement from the girl’s point of view. Should she later in life wish to resume her womanhood and marry someone else, her original fiancé must in honour kill the new one.

This type of blood feud was a curse to the country, but in the absence of law and deterrent punishment it could not be avoided, especially since it had for centuries been approved by public opinion. One insult, or one killing, inevitably provoked another killing, and the resultant feud often continued for generations, long after the original cause had been forgotten.

I remember taking refuge one evening in a house high up in the mountains, with the snow falling heavily outside blotting out the landscape. Grateful for the shelter, my secretary and I were welcomed in and offered low stools in the place of honour by the fire which was built on the ground at the far end of the room. Shortly afterwards two more men came in and sat down in the corner farthest away from the fire. One of them was magnificently dressed in a rose velvet bolero heavily embroidered with gold, the other was obviously his henchman. There was a chilly silence. I whispered to my secretary and asked who the man was.

“This is someone who has not fulfilled his blood feud,” he replied.

Coffee was presently brought in by the son of the house, and offered to all the guests in turn, but when the boy came to the newcomer, he lifted his leg and passed him the coffee under his thigh: the most insulting gesture that can be imagined in Albania. Public opinion was so strong that society “sent to Coventry” any man who failed to carry out his blood feud.

During my last year in the country I helped to compose about sixty of these feuds, most of which had been going on for a long time. I would first investigate the cause of the original quarrel, then add up the killings on either side and apportion the value of each in terms of cattle. When a balance had been struck, it would generally be found that one family owed the other perhaps ten or fifteen cows. The heads of the families concerned would then be approached to discover if they were prepared to pay or to accept the difference, shake hands and let the feud die. It was a delicate business, but well worth accomplishing.

When Ahmed Bey returned to his country he had brought with him from Jugoslavia a small group of White Russians to man his artillery. They were part of the remnants of Wrengel’s army who had found refuge in the Balkans after their defeat in Southern Russia. From them I acquired a Cossack captain as a groom, a marvellous man with horses and a first-rate fellow in every other respect. The stables were in the yard in front of my house, where there were also the outbuildings, storerooms and kitchen, with plenty of room for the pigs, the geese and my large collection of dogs. It was a common saying in Tirana that the Stirlings lived in their own house by the kind consent of their animals.

Albania was an expensive country to live in, for it provided none of the commodities which are considered essential in modern life, such as soap, groceries and drink, all of which had to be imported from Italy or Austria. There were no local servants and so we had to bring ours from Vienna. We had a wonderful cook, the best I have ever had, but the climate eventually affected her health. She became extremely bad-tempered and finally made a habit of throwing knives at the kitchen boy, so I had to get rid of her.

When we first arrived my wife and I were practically the only Western Europeans in Tirana. A year later a French biologist with a charming wife and family joined our number, and thereafter the foreign population grew so rapidly that whenever I gave a party I had to invite no less than 250 guests to avoid giving offence.

In the absence of competent doctors we did our own doctoring and on one occasion I cured myself of impetigo by using a large jar of Spratt’s mange mixture which I kept for the dogs. Malaria was the curse of the country, and the Italians went down with it regularly within a fortnight of their arrival, but not one of our household ever had it, as I had all my doors and windows wired and used to dose every member of the family with alcohol in some form or other every evening.

No ladies’ hairdresser existed, so I acted as barber for the whole family and was responsible for the initial shingling of my wife and our governess. I always used to cut my own hair in the Sudan and so had acquired some experience. Women are very critical in matters like these, so I finally learnt to turn out a very good job.

The reorganisation of the gendarmerie proceeded smoothly. I had divided the country into four areas, each with two British inspectors, and in each divisional centre we formed a small flying column, ready to move offat an hour’s notice to deal with marauders from across the frontier or any local brigands. Within a year we had cleaned up almost every organised band in the country and security was greatly improved.

One of the last of the bands in the south had been reduced, by a process of attrition, to three men. A large price was placed on their heads and they were chased around the country without much respite. One morning these three turned up on the outskirts of a village. Two of them decided to go in and try to find some food, while the third was left behind to watch their belongings which they hid at the foot of a tree. This rascal climbed the tree and hid in its branches, and when the other two came back and sat down underneath him he shot them both, climbed down from the tree and cut off their heads. These he put into a sack and carried over his shoulder to the nearest gendarmerie post. Ushered into the office, he opened the sack, rolled on to the floor the two gory heads and claimed his reward for the service he had interpreted so literally.

Tirana street scene

(Photo: Dayrell Oakley-Hill,

ca. 1935).

At the close of the First World War a committee, called the Council of Ambassadors, had been set up in Paris to determine the frontiers of the newly created States and of those States whose boundaries were still undefined. Albania was most unfairly treated since the President of the Council, the French Ambassador, had instructions to favour the Jugoslavs, who were at that time regarded as French protégés. In drawing the line of the eastern frontier between Albania and Jugoslavia, the demarcation committee very properly chose a geographical feature and kept the new frontier along the crest of a range of hills; but wherever there was a town of any importance lying west of this line, the line was bulged out in that direction so as to include the town in Jugoslav territory.

The whole of the eastern province of Albania and the Drin valley was thus deprived of the normal market towns and, in order to sell their produce, the peasants had to take their stuff by pack-pony five days’ journey across the mountains in the hopes of finding a market; clearly not an economic proposition. Consequently they never sowed more than what they thought sufficient for their own consumption. Should the harvest fail, or even fall short, in any one year, these people simply starved.

During one bad famine I was sent to the province to distribute relief in the shape of grain, maize and onions. I found the women out in the orchards picking the unripe cherries and plums off the trees. These they would pound in a mortar, mix with an equal quantity of wood-ash from the fires, make a paste of the mixture and bake it for bread. The wood-ash was included to give a certain amount of body to the so-called bread.

As I was completing my relief work there was a heavy fall of snow. I did not relish the prospect of a six days’ ride back across the high mountains in that weather, so I wired for permission to return via Jugoslav territory. Such permission being granted, I telephoned to Prizrend, the nearest Jugoslav prefecture, and the prefect very kindly came to meet me on the frontier. Over a cup of coffee in the main square he began to yawn. I remarked that he seemed very sleepy, and he admitted that he had been up till four o’clock that morning at a dance in the officers’ club. Rather incautiously I said what a pity it was that I had arrived a day too late for the party. Whereupon he immediately insisted on summoning all the officers and their families to a second dance that night. It was great fun and my hosts were kindness itself, but I found out afterwards that everyone in the town to whom I had spoken, without the guidance of the prefect, had been thrown into prison and severely interrogated.

When I got to Sarajevo next morning, my secretary, in great agitation, showed me a long story in the local papers describing how I had been arming Comitadji bands on the Albanian frontier preparatory to raiding into Jugoslavia. I did not like the look of this at all, for I had learnt enough about Serbian prisons to know that they were far from luxurious, so I decided we should make a quick getaway and catch an early train to Ragusa, the nearest port on the Adriatic. There was no Italian ship in when we arrived there, so we had to lie low in a friend’s house for a couple of days, and when at last a suitable ship did come in, we were first taken down to a small cove on the coast and rowed out secretly at dead of night. I heaved a sigh of relief when we were safely on board.

Ahmed Bey did me the honour of taking me into his confidence on most major questions of policy, and early in the summer of 1926 I advised him that since he was too weak to resist the impending encroachments of Italy on the one hand, and of Jugoslavia on the other, and since he could not face both ways at the same time, he had better make friends and come to an alliance with one or the other. I pointed out that while an alliance with the Italians would undoubtedly be to the material advantage of Albania, since Italy could lend both money and highly trained engineers for the development of the country, it would nevertheless be the more dangerous of the two solutions, in view of Italian ambitions. From Jugoslavia he would not be able to get the same financial assistance, but by allying himself with her he would enter the Balkan bloc and so be able to present a united front to Italy.

Ahmed agreed in principle with my arguments, but said that he felt in honour bound to approach the Jugoslav Government first in any case, since it was the Jugoslavs who had helped him back to power and it was they who were his immediate neighbours. Consequently proposals were made to the Jugoslavs for a form of alliance and mutual help. Very shortsightedly they turned it down. Four months later similar proposals were made to the Italian Government; they were accepted with alacrity and in November 1926 the Pact of Tirana was signed.

The terms of the pact were innocuous in themselves. Each of the parties pledged itself to lend its mutual cooperation and support in respect of reciprocal interests, and to submit to arbitration and conciliation any difference which might arise. Each further undertook not to conclude political and military agreements with any other political power, which could be to the prejudice of the interests of the other party. Because it was so unexpected, the pact caused a good deal of excitement in diplomatic circles, and the final clause in particular annoyed the Jugoslavs considerably.

When I first went to Albania, and for many years afterwards, the currency was gold and the exchange was calculated in terms of gold francs, the English sovereign being worth twenty-five, the napoleon twenty and the Turkish pound twenty-two and a half. In payment of my salary I regularly received a bag of gold coins which had to be sorted out before the total amount could be checked. Once, when my wife and I were touring the southern districts, I drew my pay at Valona and was given a small bag of 360 coins. We had planned to cross the Greek frontier and spend the night in Janina where we heard there was a really good hotel. My wife volunteered to get the money through the customs by slinging it on a tape round her waist and wearing it under her skirt. She little realised how heavy gold was; when we got to the hotel she found the tape had cut through her skin over both hips.

We returned to Albania the next day by a different route and passed the spot where, a fortnight later, General Tellini was ambushed and killed. It was his assassination that provoked the Italian bombardment of Corfu, and for the first time Europe opened its eyes to Italian aspirations in South-East Europe.

After the British inspectorate of the gendarmerie had been functioning for nearly two years, I began to realise that I was still devoting too much time to it and so neglecting my other work. It was therefore arranged for another officer to come out from England to act as Inspector-General. The man chosen was Major-General Sir Jocelyn Percy, who had been Chief of Staff to the 5th (Gough’s) Army, and on his arrival I was made Inspector-General of all the administrations except that of justice.

For two summers running we went on leave to the enchanting little island of Brioni, which lies off Pola at the head of the Adriatic. There was a large, comfortable hotel there, a wonderful swimming-pool, a golf course and two good polo grounds. The owner of the island was very keen on polo and used to go to England to buy his ponies. One year Roger Keyes, who was then C.-in-C., Mediterranean, brought his team to the island and challenged us, and after a great match they won 8-7. Our best player was Campbell of the 10th Hussars, who had played a lot in the Argentine, and the other members of the Brioni team besides myself were Baron Windesgratz and Prince Hohenlohe.

In Albania I was constantly being caught up in the backwash of power politics. The country was, in a sense, the barometer of the Balkans, and most of the strings that were being pulled came through my hands in Tirana. The main purpose in the Italian political scheme was to prevent the Slav element from penetrating farther down the Adriatic, for should Albania become a Jugoslav province, the great harbour of Valona would fall into Slav hands and the Adriatic would be closed to Italy. Albania therefore was to remain at all costs a neutral and independent State, and Italy announced that any movement of Jugoslav troops into Albania would be regarded as casus belli.

My duties entailed continual travelling and visits of inspection, on which I always took my secretary, and very often my wife as well. Ahmed Bey encouraged her to accompany me, for he knew it was good for his mountaineers and their womenfolk to see an Englishwoman travelling unconcernedly through their country. But the stages were extremely arduous, seldom less than eight hours at a stretch and often as much as ten. We took riding and pack ponies on these trips, but it was rarely possible to move out of a walk, for the going was frequently hazardous. Rounding the shoulder of a hill one would sometimes find oneself on a path so narrow that the ponies would literally have to place one hoof right in front of the other.

I found that people at home would not believe me when I described these paths, so one day, when we had just passed a particularly narrow section, I asked my wife to stand on the path, with my watch strap stretched on the ground at her feet, and then photographed her. The path was exactly one inch wider than the length of the strap; on the left was an almost perpendicular wall of rock, on the right a sheer drop of 600 feet.

At the end of one of these long, tiring days we would find shelter in one of the mountaineers’ houses, which were veritable fortresses in miniature. Only the animals occupied the ground floor, while the upper storey was reached by an outside ladder which could be drawn up at night so that the owner and his family could sleep in peace and security. The walls were loopholed at intervals, and the few small windows were placed high up so that a bullet fired through them would not hit the people inside.

However poor these mountaineers might be, guests were always welcome and treated with honour. Being very tired after a ride of sometimes over thirteen hours, we would wish for nothing else but a light supper and so to bed. But custom forbade this; a sheep had to be first killed and skinned and then dressed and cooked, while we would be regaled with black acorn coffee and plum or cherry raki. By the time the meal was ready, about ten o’clock at night, we were generally too tired to eat anything.

We would put up our camp beds in one of the upper rooms and our host, after a decent interval to allow us to get undressed, would come in, hang up his rifle, throw a rug on the floor and go to sleep across the doorway, for he was responsible for our lives while we were on his land. In Albania the saying “A guest is the gift of God” is taken quite seriously. In the morning our host would come in with his sons and brothers and sit cross-legged on the floor rolling cigarettes and asking countless questions. At this early hour, before we had had any tea and while I was still trying to shave, their visit was a rather trying ordeal […]

Early in 1927 I unearthed an Albanian plot. My secretary’s father kept a hotel in Tirana which was patronised by the factor, or agent, of a large landowner, one of the chiefs of the Dibra tribe. This chief was also a senator and was distantly related to Ahmed Bey, his brother having married one of Ahmed’s sisters. The factor got rather drunk most evenings and, in his cups, told my secretary that his wife had been seduced by his master, the senator, on whom he now planned to take revenge by giving away a conspiracy on which his master was engaged. He alleged that the senator was in the pay of the Jugoslavs, who had arranged that on a certain day Ahmed Bey should be murdered and the capital be seized by the Dibras, preparatory to an invasion and subsequent occupation by Jugoslav troops.

Ahmet Zogu in his famous

white uniform. 1926.I did not believe this involved story, which I attributed to the ravings of a jealous husband. My secretary, however, insisted that the senator was actually receiving gold from the Jugoslav legation, and so I put a man on to watch him. Sure enough, he was twice seen leaving the legation after midnight with a bag of gold in his hands. I now began to take a little more notice and called for reports on any troop movements on the Jugoslav side of the border. My suspicions were at once confirmed when I discovered that the infantry brigade at Monastir had been moved down to the little town of Struga on the Drin and been replaced by a whole division.

I refused to believe that the Jugoslav Minister himself had any knowledge of this business. At that time there were really two Governments in Belgrade, the elected Government of the people and that of an Army clique known as the Black Hand, and I later discovered that the plot had been hatched by the latter and was being controlled in Tirana by the Jugoslav Military Attaché.

Ahmed Bey was disgusted when he heard of it, for the senator was something of a friend of his and was being quite heavily subsidised by Ahmed himself. The story was again carefully checked and there seemed to be no doubt of its truth. We had a long discussion as to what should be done. It was obvious that as President, Ahmed Bey could not accuse a legation credited to his Government of plotting against his life. At the same time the danger could not be ignored; it was very real not only for the President and for Albania, but for the whole world. For if Jugoslav troops occupied any part of Albania, Italy would be certain to declare war and it would be difficult to localise the conflict.

We found that our only solution was to arrange for the factor to shoot the senator and then provide him with a safe conduct out of the country on a false passport. The factor duly carried out the sentence and was smuggled over the border into Greece. There was a great stir and the senator was given a state funeral, with all the military out and a couple of bands. I received a printed invitation but did not attend. The Jugoslavs, I know, always suspected I had something to do with this business, but were never quite sure.

Some months later they again started massing troops along the frontier. The British legation in Durazzo was so ill-informed and so blind to events that I decided to go to Rome and see our Ambassador, Sir Ronald Graham, who was an old friend of mine. After hearing what I had to say, he told me to go straight home and report to the Foreign Office.

On my arrival in London I was given an immediate interview by two young gentlemen of the Eastern Department. Instead of pumping me, as wise men would have done, and seeing if my information checked up with theirs, they did all the talking and gave me clearly to understand that they knew far more about the matter than I did. I apologised for wasting their time, informed them that they were certainly wasting mine, and withdrew. I then played my last card. I wrote a letter to The Times in which I said:

“In view of the world situation and the repercussion which any disturbance in the Balkans is bound to entail, I think it useful that the following information should be in your hands.”

I then outlined the general situation and continued:

“Should this situation arise, the clauses of the Treaty of Tirana would undoubtedly be brought into action. This would mean the stiffening of the Albanian forces by Italian troops, guns, supplies, etc.

It is difficult to foresee the results of such a situation but it is obvious that it would mean certain war between Italy and Jugoslavia and the making of a very pretty trouble into which Bulgaria, Roumania and Hungary might be tempted to step.

I feel very strongly that the greatest and indeed the only safeguard against such a state of affairs as I have outlined, is publicity–before the event and not after.

I am aware that the foregoing is not suitable for publication but it might be beneficial to the world if, by a carefully worded article, you could convey to the Jugoslav Government that the situation was not unknown in London.

I may add that I have no doubt of the general accuracy of my information.”

As a result of this The Times published a leading article next day, which conveyed in smooth terms a definite warning to the Jugoslav Government, and I received the following letter from the Foreign Editor:

Dear Stirling,

Your letter could not be kept entirely unpublished. We published it in a paraphrase and it went to print a few hours after the Italian Ambassador made a formal complaint to the Foreign Office about the attitude of the Jugoslavs.However, so far from doing any harm, your news and what we have published have, I think, enabled The Times to do a good stroke for Balkan peace. The one danger in the situation was the absence of publicity. If a sudden flare-up had occurred without anybody knowing why, goodness knows what might have happened. It was particularly necessary to give the French a hint to curb their Jugoslav friends. At present there is talk of a Military Mission inspecting the frontiers, etc., but I feel myself that we have passed rather a nasty corner.

I should like to thank you very much on behalf of the Editor for your most valuable news.”

One summer we spent our holidays up in the highest Albanian mountains, my wife and I, our daughter Elspeth and her Swiss governess, one of the secretaries from the American legation, my own secretary and my Cossack groom. We motored up the Scutari road as far as the Mati river, then struck off east into the heavily wooded Mirdita country, home of the largest and most powerful Christian tribe in the north.

One of our first nights out we camped beside a church. The priest offered us the use of his house, but we knew that there would be too many of those little creatures which no one cares to mention but which everyone dreads, so we said we preferred to sleep in the open.

“Well,” said the priest, “if bad weather comes up, don’t hesitate to use the church.”

About midnight a terrific thunderstorm broke above our heads and the rain came down in sheets. Hastily gathering up our camp beds and belongings, we rushed into the church, where we disposed ourselves for the rest of the night along the central aisle. I woke up in the morning to a quiet droning sound and, looking round, saw the priest, clad in magnificent green and gold vestments, unconcernedly saying Mass at the high altar. It was a problem in tact and I thought the better part would be to feign sleep again.

Farther up in the mountains we stayed for several days in a ruined monastery, where the priest, a highly educated Italian-trained Albanian, led a lonely life shut off from the rest of the world. Few of his flock could read or write, so that they could afford him no intellectual stimulus, and he had read the handful of books he possessed over and over again. When I got back I was able to send him a large box of books from Rome which I am sure must have cheered him up. These priests take their calling very seriously. Every Sunday morning he would say Mass in his own church in the valley, then climb 4,000 feet to the high pastures and say another Mass for the shepherds.

One Sunday morning we attended this Mass, which was one of the most moving and beautiful ceremonies I have ever witnessed. The altar was simply a flat rock, over which was spread a cream-coloured brocade altar cloth for the sacred vessels. The shepherds and their families assembled, the men on the one side, the women on the other, while their flocks were left herded close by, guarded by dogs. They all knew the hymns and chants by heart, the men and women singing alternate verses, and their voices at this altitude seemed to hang in the air, and Nature itself joined in the service.

Gjon Marko Gjoni, Prince of the Mirdita, had invited us for the wedding of his eldest son and asked me to be the principal witness. He explained that according to custom I would thus become a blood relative of his family, so that none of his other sons, alas, could ever marry my daughter. His family had ruled the Mirdita without intermission since the middle of the fifteenth century and Gjon Marko Gjoni was, in addition, Paramount Chief of the Dukagjini, the five Catholic tribes of the northern mountains. He was a force to be reckoned with for, at his call, five thousand riflemen would assemble under his orders within three days, and as many more from neighbouring tribes a few days after.

Gjon Markagjoni (1888-1968),

kapidan of Mirdita.His house was built of solid stone and designed primarily for defence. From the small windows, scarcely more than loopholes, one had a wonderful view over mile upon mile of narrow winding valleys and pine-clad slopes, while behind the house were the sheer rocky crags of Mali Shenjt, the sacred mountain, rising 6,000 feet above the distant gleam of the sea.

On our arrival we were welcomed by salvoes of ball ammunition fired into the air. Every guest was so received and the amount of ammunition that was expended during the week we spent there would have sufficed for a quite considerable battle. The bride had not yet arrived for, according to custom, the principal guests must first be present to receive her, her reception being of even greater social importance than the wedding ceremony itself.

Her father’s house was two days’ journey away, and an escort of some two hundred armed Mirdita mountaineers had already left to fetch her over the difficult trail. She had left her father’s house on horseback, and the only member of her family allowed to accompany her was her mother. Tradition demanded that she be seen by no one and so she rode enveloped in a veil of scarlet silk, mounted on a wire framework supported on her head. To ride thus blindfolded over those treacherous mountain tracks was surely a test of nerves from which even our own Amazons might shrink.

The sun was setting as the bride and her cortège came into view, the escort winding along in single file across the precipitous rock face, each man firing his revolver or automatic as he advanced. The noise as the eight or nine hundred assembled guests replied in kind may be imagined. The poor girl had to be lifted off her horse. She was so stiff from the constrained attitude which custom decrees she must adopt that she could hardly stand, and had to be propped up against a wall while she received the salutations of the crowd. She was then taken by her bodyguard to a neighbouring spring where, by ancient custom, she filled a pitcher of water which she poured out for each member of her new family, to signify her capacity for domestic life and emphasise her subservience to her husband’s kin.

Merrymaking and feasting continued every night until about an hour before dawn. Throughout the day guests arrived, some from places even five or six days’ march away, and each party brought its quota of gifts, a few sheep, an ox or two, or a goat, each according to his means, but humble or great, all were received with the greatest ceremony and with a fusillade from the rifles of all present. The average number of guests, as they came and went, may be judged from the fact that on one morning 5,000 cups of coffee were served before the midday meal, and the same night 700 people sat down to dinner, in addition to the party of distinguished strangers who were entertained in one of the great upper chambers. The following details of the food and drink consumed may be of interest to heads of families who are considering marrying off their daughters: 5,000 lb. of meat, 700 lb. of rice, 450 lb. of sugar, 280 lb. of coffee; 660 quarts of raki, a potent local spirit, and 2,000 quarts of mastic, a spirit which when mixed with water becomes cloudy and milk-like–except in its effects!

The courtyard was crowded with guests, with others scattered in groups by the edge of the forest, and the brilliantly coloured and embroidered robes of the women against the deep green background of the pine trees made an unforgettable picture. Both men and women sang almost continuously, sometimes accompanied by a three-stringed wooden instrument shaped like a ukelele, while the women danced together in groups and the dance was punctuated by bursts of rapid fire.

Taking the bride to the groom

(Photo: Gerhard Kiesling, 1959).On the third day after the bride’s arrival the wedding ceremony took place. One of the rooms of the house was converted into a chapel for the simple service, at which the parish priest officiated and only near relatives were present. The bride was only sixteen, but she was tall, with a commanding presence, and made a most impressive figure as she was led in by the Prince. She was dressed in full national costume, with a head-dress of gold and scarlet silk bound round with a fillet of gold from which hung countless small gold coins which tinkled as she walked. Her undercoat was of red brocade, over which she wore a long sleeveless coat of white felt, heavily and marvellously embroidered in red, blue and orange silk. Her full white linen trousers were gathered at the waist by a multi-coloured silken scarf from which there fell an apron embroidered in the famous Kossoviet manner. Both coats were open in front to disclose a pleated skirt festooned with fine rows of finely chased and wrought gold chain, each link about half an inch wide. From the chain there hung some thirty immense gold coins, old 100-crown pieces of the Austrian Empire.

The bridegroom was in the usual national costume of the mountaineers, with tight-fitting white felt trousers, heavily braided in black, and a cross-over bolero so thickly embroidered with gold that it looked like a golden cuirass. A plain white felt cap completed his costume. He was young, barely eighteen, with a handsome, intelligent face. His father had decided that his marriage should not interfere with the completion of his education and he was shortly to be sent to some of the great capitals of Europe to finish his studies, and finally to England.

A curious feature of the wedding customs is that the bridegroom must take no notice of the bride–although he has never yet seen her–either on her arrival or afterwards and must pretend to be unaware of her existence. Further, to ensure that the bridegroom’s attention shall be in no way distracted from the entertainment of his honoured guests, the bride herself must sleep with her mother for the first two nights after the wedding.

After many discussions with Ahmed Bey on the best means of stabilising the Government, we came to the conclusion that elections in the Balkans, particularly presidential elections, were disturbing factors which usually led to bloodshed. We decided, therefore, to ask Parliament for powers to create a dynasty and to nominate Ahmed Bey as King. These powers were granted in 1928; Parliament voted for a change in the Constitution and Ahmed Bey was named King Zog. The title he adopted, “King of the Albanians” instead of “King of Albania,” irritated the Jugoslavs since there were at least three-quarters of a million Albanians living in Serbia.

Minorities of this kind always presented a problem. The Albanians living in Jugoslavia were undoubtedly oppressed; their children were forbidden to learn Albanian in the schools and there were severe restrictions on the sale and disposal of their land. To the south there was the problem of the Greeks living in Albania, and the Albanians living in Greece. The Greek Government claimed, and still claims, that the greater part of Southern Albania carries a Greek population. As a matter of fact, if a line were to be drawn fifty miles north of the frontier, and another fifty miles south of it, as many Albanians would be found to be living in Greece as Greeks living in Albania. Many of the people in the south, although Albanians by race, speak Greek in their everyday life, partly because their trade is almost exclusively with Greece, partly because their religion is Greek Orthodox; but their language does not make them Greeks, as Greek propaganda would have it.

The Pact of Tirana was followed a year later by the Treaty of Tirana, and streams of Italians began to pour in, advisers and technicians for the development of the country. With them came loans of money for the Government, and the establishment of a military mission to train the Army. General Pariani, one of the best officers on the Italian General Staff, commanded the mission. King Zog was somewhat dazzled by the importance of being in direct alliance with an almost first-class Power such as Italy, and he unfortunately allowed large sums of money to be deflected from the upkeep of an efficient gendarmerie to the requirements of a showy but useless army–useless since such an army could never be strong enough for a war of aggression, while for defence the Albanians could rely on the great mountains and their own aptitude for guerrilla tactics for which a regular army would be ill-equipped.

Meanwhile, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company had acquired a concession from the Albanian Government to prospect for oil. After drilling in a number of places, an oil-bearing stratum was discovered in the low hills north of Valona, and several wells were sunk. The quantity of oil found was considerable but the quality was poor. It was so thick that it was almost impossible to pump, so that a refining treatment at the wellhead would have been required before it could be piped down to the coast for shipment. At world market prices this was not a lucrative proposition for the company, so the concession was offered to the Italians, who accepted it at once. There was no oil available to Italy that did not lie beyond straits which could be closed to shipping in the event of war; hence the eagerness of the Italian Government to gain possession of the Albanian oil which, although not an economic proposition, was nevertheless a major strategic necessity.

After visiting the oilfields and inspecting in the neighbourhood of Valona, I rode up the shores of the gulf and came across a small stream full of trout. Even I could catch them, and I am no fisherman. The stream rose up in the limestone cliffs and ran a short course of about seven miles to the sea. As I sat on the bank eating lunch, an old peasant came up and began talking to me. To my surprise he spoke excellent English, and explained that he had once been a butler in an English household for a number of years. He remembered the days when this stream had belonged to an English syndicate and he had seen as many as seven rods at a time fishing the water. King George V, in his younger days when in the Navy, had come and fished here, and much earlier, when Corfu was still occupied by us, and before Gladstone had restored the island to Greece, rich Englishmen used to come over for the fishing in this stream and also for the wonderful woodcock shooting.

As the years went by the Italians gradually began to turn against me, not for personal reasons but through the policy of their Government. They felt that I was the one obstacle to their gaining control of King Zog, since he was a close friend of mine and, to a certain extent, took my advice. At the same time the local political leaders feared me since I knew so much of their murky past and they disliked my influence with the King. The Jugoslav Government was also very suspicious of me.

“The Jugoslavs hate me,” the King told me one day, “but they dislike you even more and you must be very careful when you go anywhere near their frontier.”

My position in the country was becoming daily more insecure, so that finally I felt safe only when I was up in the mountains with the tribes. In the circumstances, I reckoned that my usefulness in Albania was coming to an end, and in the spring of 1931 I resigned my post and returned to England.

The outstanding phenomenon during my service in Albania had been the rapid rise to power of King Zog and the founding of his dynasty. What made his rule so different from that of most Balkan leaders was his ability to give his people, who were the most turbulent and individualistic in the whole of Europe, peace and a very considerable degree of prosperity over a period of fifteen years. Of all the statesmen in the Middle East–and I have met most of them–I consider Zog to be by far the most brilliant, the most cultured and the most far-seeing.

The dastardly and treacherous invasion of his country in the spring of 1939 was one of the series of Nazi-inspired crimes on the continent of Europe; and the British Government, by meekly acquiescing in this act of aggression and refusing afterwards to recognise King Zog, helped to pave the way for the rise of Hitler which nearly brought about our downfall.

[excerpt from: Lt.-Col. W. F. Stirling, Safety Last (London: Hollis and Carter, 1953), p. 124-157.]

TOP