| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1959

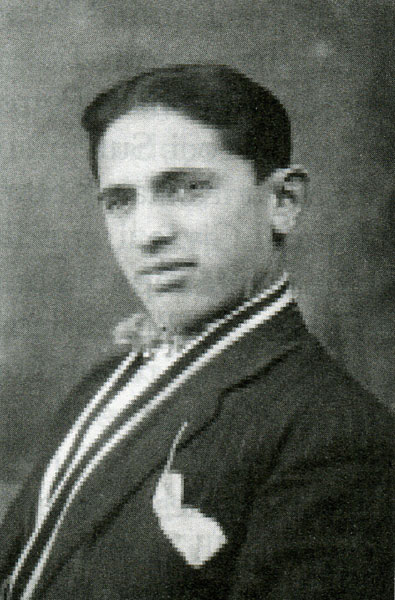

Ali Këlcyra:

Historical Reminiscences (1923-1936)

Ali Këlcyra (1891-1963).

Political figure Ali Këlcyra (1891-1963), also known as Ali bey Klissura, was born in Klissura (now Këlcyra) in the Përmet district of southern Albania. After studies in Constantinople and Rome, he served as a member of parliament (1921-1924) until the fall of the Fan Noli government in late December 1924. Klissura was a democratic nationalist, patriot and idealist, remembered in particular as a great speaker who used his rhetorical skills to attack dictator Ahmet Zogu and his cohorts. In exile, he headed the emigré Bashkimi Kombëtar (National Unity) organization, founded in Bari in 1925. The Zogu regime sentenced him to death in absentia. In 1942 he was among the founders and leading figures of the Balli Kombëtar (The National Front) resistance movement. Ali Këlcyra fled to Italy in October 1944 where he was later a member of the Free Europe Committee. In this extract from his political memoirs he denounces the dictatorship of Ahmet Zogu and the British commercial interests that promoted it.

The Results of the 1923 Elections

The government headed by Ahmet Zogu lost its majority in parliament when his People’s Party fell apart under the weight of fierce criticism from the opposition, and was forced to hold elections to the Constitutional Assembly at the end of 1923. These elections were held in a spirit of complete freedom because the government was unable to influence them even if it had wanted to. The opposition was on its toes and very watchful. Unfortunately, the result was bad representation for the country from the point of view of parliamentary activity. The three major factions now represented in parliament were:

1. the government faction in favour of Prime Minister Zogu;

2. the opposition faction in an open struggle with him (both of these factions arose from within the People’s Party); and

3. a third faction consisting of figures who were considered not only conservative but reactionary. This group profited from the extreme polarisation between the two other factions and got its own members into parliament who were both against Zogism and against the opposition. They detested the Zogu dictatorship with all the negative effects it was having on the country, but on the other hand, they were fearful of the agrarian reform that the opposition intended to implement.

None of these factions had the majority needed in parliament to take over the reins of power democratically with requisite impetus. The Constitutional Assembly began its work in early 1924. The government of Zogu remained in power for a further two months as there was still no majority, since no two factions could reach an agreement. In many patriotic circles, both in Albania and abroad, responsibility for this chaotic situation was rightly or wrongly attributed to Ahmet Zogu who was openly accused not only of endangering international relations with his adventures, but also of impeding government activity with his plots and intrigues within the country.

Although the situation in parliament was chaotic, the opposition was convinced that it could reach power by legal, i.e. parliamentary means. It enjoyed intellectual superiority, indubitable parliamentary competence, and prestige among the population in view of its patriotic and moral principles. These were not affected by private ambition or interests and, as such, were attractive for the masses of the population. The opposition was convinced that within a short period of time, it would be able to destroy the People’s Party in parliament and attain its goal of driving a wedge between its two opponents in the Constitutional Assembly and of contributing to the creation of an educated political elite in the country.

The Attempt to Assassinate Zogu

Unfortunately, the fierce polemics going on in parliament had a strong echo in the population that was as yet unused to life in a parliamentary democracy. As a consequence of the extremely politicised atmosphere, with much vociferous strife among the factions in parliament, a sixteen-year-old lad called Beqir Valteri from the Mat region attempted to kill the Prime Minister when the latter was entering parliament. He shot at him four or five times with his revolver. The Prime Minister, who had received several flesh wounds, entered the assembly drenched in blood. The moral and political effect of the assassination attempt was enormous, and the consequences of the incident proved to be extremely negative for Albania.

Beqir Valteri (1893-1945).

When he surrendered, the would-be assassin initially told the authorities that he had attempted to shoot the Prime Minister because he considered him a dangerous figure for the future of the nation. The government party immediately accused the opposition of being behind the shooting, but the opposition was not ruffled by these accusations. On the contrary, it stated that it was willing to give the government its full support (the assassin already being in custody) and use all of its energy to determine whether there had been a plot and to act decisively against all those involved, be they from within parliament or without, but that it would only go along with legal means. To distance itself publicly from any moral responsibility and to convince the government that it did not intend to impede investigations, the opposition also accepted a government proposal, though it was in itself unlawful, that the assassin not be taken to prison, but be held in a special location under the supervision of the parliamentary guard, whose officers were extremely loyal to the Prime Minister. In the interests of state, the opposition in parliament also kept silent and did not demand an enquête [parliamentary inquiry] when it learned that the young would-be assassin had been tortured by these officers, into whose hands parliament had placed him. The assassin was tortured to force him to admit that he had been incited by one of the opposition deputies to shoot the Prime Minister. As a consequence of the mistreatment, the deputy Avni Rustemi, considered one of the Prime Minister’s fiercest foes, was summoned by the investigating judge to respond because the authorities now accused him of having incited Beqir Valteri. The assassin then stated the following before the investigating judge and before Avni Rustemi: “I declare that Avni Rustemi incited me. I have been forced to make this statement by the officers of the parliamentary guard who not only tortured me but left me hanging by the arms for twenty-four hours. No, I hereby state once and for all in front of you that I acted purely in accordance with my conscience and that no one incited me to carry out the assassination attempt!” The opposition members of parliament once again took no measures to censor the government even though they believed that their freedom and honour had been violated by the actions of the authorities, actions that were not only illegal but also inhumane. The wounded Zogu, who had now taken to bed, nonetheless, officially stepped down from his position as prime minister and was replaced by his one-time father-in-law, Shefqet Vërlaci. This change of power was only superficial, however – just for the eyes of the public – because in reality Zogu continued to rule the country. The ambitious Zogu tried all the means available to him to make use of the assassination attempt to compromise his opponents in parliament, if not legally then at least morally and politically. When he realised that all of his endeavours in this direction had failed and that the shooting now forced him to use his trump card, i.e. terrorising his opponents with physical attacks carried out openly, with government collusion, Avni Rustemi was murdered.

The Murder of Member of Parliament, Avni Rustemi

Several weeks after the above-mentioned attempt to kill Ahmet Zogu, Avni Rustemi was assassinated on the streets of the capital city in broad daylight. His assassin was never found. The murder had all the signs of an assassination carried out by the government.

Bust of Avni Rustemi

in his native village of Libohova

(Photo: Robert Elsie, October 2012).

Avni Rustemi enjoyed great prestige in the population for the service he had rendered to the nation, as we have explained in our comments on the Congress of Lushnja. Zogu should have known what impression would be created by Avni’s murder, not only in intellectual circles but among the broad masses. Alas, such an assassination inevitably caused great turmoil in public life. But in reality, Zogu was interested in provoking such turmoil himself in order, one way or the other – i.e. by the capitulation of the democrats under his fist or by natural reaction – to impose the dictatorship that he had been scheming over for ages. Avni Rustemi’s murder was an open provocation to the opposition and constituted a direct assault on democracy in Albania. The opposition had absolutely no doubt about this. We were not certain whether Zogu was incited by any foreign influence to take such a drastic step or whether it was his own decision to play his trump card in order to present the foreign governments supporting him with a fait accompli.

Many intellectuals, officers in particular, swore on the corpse of Avni Rustemi that they would take bloody revenge as a matter of national honour. Without any exaggeration, it can be said that, with the assassination of Rustemi, democratic and nationalist circles in the country more or less rose in revolt. They resolved to attack Zogu’s home in the capital, where he was held up with over one hundred armed men. I was personally in favour of such an assasult. This movement was, however, suppressed by Luigj Gurakuqi, a peace-loving man and a foe of murders and armed uprisings to solve political problems.

Since the murder of Avni Rustemi had all the signs of a government plot, the opposition decided to declare that, unless the true perpetrators of the crime were captured within forty-eight hours, it would withdraw, so to speak, to Aventino, in this case to the south of Albania, and inform the population that its representatives could no longer remain in the capital because they enjoyed neither security nor freedom of speech. They felt threatened by government assassins. In other words, the Albanian democrats used the same tactic employed several months thereafter by the Italian democrats, following the assassination of Matteotti. Forty-eight hours later, as the government was not in a position to take any measures, the opposition deputies and all of their intellectual supporters took the body of the dead Rustemi and departed for Vlora. This was the first grand step in a national uprising.

The Revolution of June 1924

The members of parliament who withdrew to Vlora formed a “Revolutionary Committee” under Fan Noli, including Qazim Koculi, Spiro Koleka, Koço Tasi and Ali Këlcyra representing southern Albania; and Luigj Gurakuqi and Xhemal Bushati representing northern Albania. Within a few days, all of the creative forces in the country, both civilian and military, were assembled in this committee, which set about to rise against the government in power. Twenty-four hours after the beginning of concerted action between the forces of the north and south to move on Tirana, the forces of the June Movement, firing hardly a shot, entered the capital.

Fan Noli (1882-1965).

The June Movement was in essence nothing more than a military parade. Zogu hardly had time to get away with his ministers and faithful supporters. Some of them escaped to Yugoslavia, others left for Italy. The opposition victory was complete, swift and without casualties. The forces of the Movement entered Tirana in an orderly fashion. Later unfortunately, problem arose.

Our opponents at the time criticised us bitterly for the following:

1. we overthrew a legitimate government created from popular representation;

2. we made use of the army and, with deceitful propaganda, we incite school children to take part in the uprising.

3. the population was in fact against this uprising that we were forcing upon them.

All these things may be true. But even if they are, they in no way compromise the leaders of the movement, morally or legally. We did not set about to seize power illegally from another political party. The aim of the movement was solely patriotic and had nothing to do with party politics. The aim of the movement, as has been explained above, was to put an end to a perilous mixture of international plots against the country. In such a situation and with a population inexperienced in the ways of politics, an armed uprising was not only just; it was also an obligation imposed by our sense of patriotism. One cannot say that justice was infringed upon, since Fan Noli was not a dictator. It was the young people and intellectuals who propelled Fan Noli to power but, as soon as they did so, they decided to remove him from politics in the first elections that were to be held at the end of the year, and to allow him to deal only with matters of religion. This was the categorical position that we took in a statement presented to the ministers of Great Britain and Italy in Tirana. None of the religious communities wanted Archbishop Fan Noli as their prime minister. Indeed it was the Orthodox community that was most opposed to him. […]

The Administration of Fan Noli

First of all, a distinction must be made between the June Revolution and the administration headed by Fan Noli, which the revolution brought to power. We may be proud of the former, and of all the uprisings and movements in which we have taken part, but we cannot say the same thing of the latter. We accept the fact that responsibility for the choice of Fan Noli as head of government fell more upon us, the younger intellectuals, than it did upon the older figures. The latter, especially Luigj Gurakuqi, were strongly opposed to Fan Noli, an Orthodox archbishop, as the leader of a rebel movement, and all the more so as head of the Albanian government.

We, the younger figures, backed Fan Noli for the following reasons:

1. Fan Noli had a solid international reputation which he had gained as Albania’s representative at the League of Nations. None of the other younger figures of the movement were known abroad. As we intended to rise against the government in power, we needed a figure who was known abroad. We were afraid that ministers Eyers, Pasić and others who supported the Zogist dictatorship would accuse the June Revolution publicly of attempting to usurp power, like thieves, from a legitimate government, similar to the accusations made by General Piacentini concerning the Vlora Uprising.

2. From an intellectual perspective, we considered Noli to be the most suitable person to rule the country.

3. The young people regarded Fan Noli as a proponent of North American democracy.

4. Because we were still full of youthful enthusiasm, we were proud to put an Orthodox archbishop at the head of a country that, ten years earlier, had been in the throes of a fanatic Muslim uprising.

Of course, none of us ever supposed that Noli, with his cultural and moral qualities and after his studies in America, would let himself be influenced by the intrigues of Kostandin Boshnjaku and become a follower of Soviet culture and, whether intentionally or not, become a tool of Stalinist propaganda. This was a tragedy for our country, for which we must bear the responsibility. But our mistakes and all of Fan Noli’s failings were not the main reason for the tragedy that shook the nation. It was rather foreign imperialism that was to blame, because the government was not really aware of what Fan Noli was doing, and after all, he did not commit any great national or international sin. For example, he did not enter into any secret agreements with representatives of the Soviet Union, as did the representative of the British Legation in Tirana, to transform Albanian legations in the Balkans into nests of Soviet espionage, as we have explained (according to information from Lebedev).

The political mistakes of the Fan Noli administration are the following:

1. He did not keep proper order in Albania. He gave too much leeway to young people inspired by political extremism. They abused this freedom and undermined the prestige of the democratic nationalists in the population, until he was fed up with the injustices they were committing.

2. Without good reason and without informing the Council of Ministers or the Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Prime Minister met with the Soviet ambassador at a time when major countries like Britain and France had no diplomatic relations with the Soviets. When the Russian diplomatic mission arrived in Tirana, without the government’s knowledge, the latter, aware of the bad impression this left in the country and in international diplomatic circles, was obliged to declare the letters of credence of the Soviet diplomats invalid, and the Soviet mission withdrew immediately.

3. In the autumn of 1924, Fan Noli held a sarcastic speech at the League of Nations criticising the Dawes Plan on German reparations for war damages. The tone of his speech was incompatible with the position of the representative of a small country.

These errors led, rightly or wrongly, to Fan Noli being considered by our opponents as a tool of Moscow. The governments of the countries that were against democracy in Albania used these events and the impulsive doings of the Prime Minister as a pretext for imposing a dictatorship upon the Albanian people, a dictatorship they had long been scheming about.

The Dictatorship of Ahmet Zogu and the International Plot to Impose it upon Albania

Just as we would never have imagined that Fan Noli, a proponent of American culture, would turn into the tool of the Soviet agent, Boshnjaku, we would also never have suspected that Great Britain, which had the same moral obligations to support the League of Nations that the United States of America now has to support the United Nations, would take the initiative and contrive an international plot against a tiny country like Albania, a member of the League of Nations, for base economic or political interests. The plots and schemes of the British Legation in Tirana, which had such repercussions on the international scene, had as their prime objectives:

Ahmet Zogu (left) and Ceno bey Kryeziu (right).

a) to get a concession for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company under favourable conditions, 2 or 3% lower than the other bidders, and this, to the detriment of a little underdeveloped country with a starving population devastated by the destruction wrought by war after 1912;

b) to impose a dictatorship upon the wearied Albanian people by which it intended to turn us into a pawn to back the interests of the British Empire in international politics.

To further its base interests, not only did the representative of Great Britain in Tirana do great damage to the Albanian people – and they are still suffering from the consequences – but he also damaged his own country from a moral perspective, in particular at the League of Nations. In view of its international interests, one might have assumed that enhancing the prestige of the League of Nations would have been a major goal of British foreign policy.

According to information we received from various sources, when international forces resolved to intervene and overthrow democracy in Albania, Ahmet Zogu, who was waiting in the wings in Belgrade as a distant sovereign on an improvised throne, made secret agreements with a number of foreign countries:

The Constitutional Assembly in Tirana declares

the monarchy and proclaims Ahmet Zogu

as King of the Albanians, 1 September 1928.

1) With representatives of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company for the oil concession under conditions set forth in a contract signed by the Tirana government in 1923. In this connection, the future dictator of Albania received 50,000 pounds sterling for… his expenses in the operation he was preparing!

2) With the Belgrade government that agreed to provide auxiliary forces (consisting of Kosovo Albanians, Macedonians and Wrangelites), not to mention the activities of the Yugoslav army and artillery along the border. In addition, the Yugoslav government gave the future Albanian head of state 22 million dinars for his expenses in the operation. Under the agreement, Zogu was obliged to promote the political and military interests of Yugoslavia in Albania. He was not to raise an Albanian army because this would have conflicted with Yugoslav political objectives in the Balkans, but was simply to maintain auxiliary forces. He was also to review the Albanian-Yugoslav border issue in accordance with urgent requests from Belgrade, such that strategic sites such as Vermosh and Saint Naum, both inhabited by Albanians, would be given to Yugoslavia. In exchange, the village of Lin was to be given to Albania.

3) With the Athens government, under which he was obliged, after taking power, to open Greek-language schools and promote Greek-language education in southern Albania, organised by the Orthodox Church.

4) Greece regarded these constant demands as its prime strategy for hellenising the Orthodox population of Albania. As compensation for these concessions of vital interest to our people, the Greek government guaranteed to provide Zogu with military support along the border and with 12 million drachmas to cover the requisite expenses of the invasion.

5) Zogu did not make any written commitment to fascist Italy because, according to what we learned from Palazzo Chigi (for various reasons that we have elucidated in our comments on Albania’s position in international relations), Mussolini did not want to get involved in imposing the dictatorship and preferred to leave all the moral responsibility for this coup d’état, organised against his opponents on the international scene, to the Balkan states and in particular to Great Britain. The Duce hoped up to the very last minute that, when the democratic nationalists became aware of the advance of Zogist forces on Tirana and thus, so to speak, of the invasion by Yugoslavia with the approval of England and with the silent approbation of the League of Nations, they would be forced to seek support from him in order to defend the country’s independence and territorial integrity. But here, the Duce was wrong. The Albanian nationalists, who had once saved the country by the skin of their teeth, preferred death to emigration, which would have been equivalent to dishonouring both themselves and the fallen martyrs of the nation. It is incomprehensible how he could have thought that those who had struggled to put an end to the Italian protectorate in 1920 would ever have sought Italy’s assistance. The Italian Legation suggested such a strategy to us in Tirana. We declined their offer.

Nonetheless, for the reasons mentioned above, Italy did not wish to participate openly in supporting Zogu. In order at least to affirm its neutrality in the violent intervention that took place against Albanian democracy, Zogu promised Rome economic and financial concessions in compensation, through his former father-in-law, Shefqet Vërlaci, and the member of parliament, Andon Beça, who were in Rome at the time.

After issuing such promissory notes to foreign governments to the detriment of the country’s resources and of the constitutional order of the Albanian people, and after having been informed by the Yugoslav Foreign Minister Ninčić that everything was ready, Ahmet Zogu set off triumphantly to take over the country with foreign assistance. In the third week of December 1924, at a time when the Albanian people were holding peaceful elections guaranteed by international treaties, they were startled from their sleep one night to hear that all the country’s borders were in flames. Greek and Yugoslav artillery were bombing Albania. The regular and auxiliary forces of these countries were on the march, together with marauding bands expedited by the Belgrade government to accompany Zogu. This was the realisation of the international plot.

Mr Eyers, the Minister of Great Britain in Tirana, did not fail to make a final contribution to the realisation of this plot, to which he had given his discreet support from the start. One could easily state that the success of this plot marked the zenith of his diplomatic career. While the operation was underway, he met with many Albanian patriots, both civilian and military, and appealed to them: “Albanian patriots! It is useless to fight and resist. The fate of Fan Noli’s government and its supporters has been decided. They have been condemned by high-level international circles as tools of Soviet Russia. Even if Zog and his forces do not triumph, the divisions of Greece and Yugoslavia will receive orders to invade Albanian soil and cleanse it as necessary, as happened in Hungary under Béla Kun”. When the Albanians heard these words, they were dumbfounded and could not believe their ears.

The national front, taken by surprise by the unexpected invasion, demoralised by the propaganda of Mr Eyers, and wearied and angered by the behaviour of young extremists who, encouraged by others, tried to imitate communist and fascist tactics and thus compromised the dignity of democratic nationalists in public opinion, was virtually ploughed under without showing any resistance whatsoever. It was a tragic day in the history of our nation.

Zogu entered the Albanian capital to the sound of drums, at the head of the army prepared for him by Ninčić and the diplomatic service of Great Britain. Here, six months earlier, he had been forced to flee in the night so as not to fall into the hands of the vanguard of democratic nationalists that was approaching the city. The servile parliament of the new dictatorship later ignobly called this victory, realised with foreign arms, the “Triumph of Legality.”

One thousand patriots and intellectuals left the country in sign of protest against foreign occupation.

The above-mentioned words of propaganda of Mr Eyers in 1924 still echo in our ears, reminding us of the voice of Colonel Hill, an officer of His Britannic Majesty, who after organising the Albanian Gendarmerie for a long period of time (1929-1938), returned to the mountains of Albania during the resistance (1940-1943) and via radio from the heart of the greatest empire in the world, called upon our comrades and fighters in August 1944, saying: “Men of Balli Kombëtar! Leave your organisation and join the National Liberation movement because your leaders have been compromised as collaborators with the Nazis. Have no fear of the extremist tendencies of the communists because today’s communists are not the ones you know. Stalin has given orders for the churches to be opened and for religious freedom”!

What a curious coincidence and irony of fate – our patriotic democrats were accused by Mr Eyers in 1924 of being communists and by Colonel Hill in 1944 of being fascists! These orators of the British Empire spoke openly to the Albanian people in the name and on behalf of two opposing ideologies, asking the democratic nationalists to distance themselves from them. These two gentlemen, scions of a country considered to be the cradle of democracy, at two tragic turns in our national history, 1924 and 1944, demoralised the armed forces of the democratic nationalists and paved the way for dictatorship in Albania. The democratic nationalists, accused in turn of being communists and fascists according to the interests of the British Empire, were exiled from their country for years on end or, even worse, found themselves interned amidst barbed wired and mud in the “R” camps of Terni and Rimini, solely because they did not obey London’s orders to work for the Bolshevists. Our national tragedy has continued now for 40 years and, it would seem, will continue until we die or until a Messiah comes to save our oppressed and terrorised people from European imperialism and, at the same time, from the running-dogs of pan-Slavic communism that it fostered. […]

Likoff and M. F. Eden, the Foundation of the Konare, the Formation of the Bashkimi Kombëtar Organisation, and the Murder of Luigj Gurakuqi

The rather shabby grave of

Luigj Gurakuqi in Shkodra

(Photo: Robert Elsie, July 2011).

Before the invasion of our country by the neighbouring states that were actively scheming to realise an international plot aimed at imposing a dictatorship upon our people, a large section of the Albanian elite was forced to flee the country and go abroad, not so much out of fear of the new rulers but in sign of protest against the injustice done to our people. Many of these emigrants arrived in Brindisi and Bari on the steamship Mektovic. They were met on the docks and in the Italian capital by two figures who represented two rival currents of European imperialism at the time: Mr Likoff, the Bulgarian communist leader, former deputy of the sobranje [parliament] and delegate to the Comintern; and the English Major M. F. Eden, an old friend of Albanian democrats who had played an extremely important role as an advisor in the convening of the Congress of Lushnja and in preparations for the liberation of Vlora. These two gentlemen, who represented opposing ideologies and national interests, told our Albanian patriots the same thing: “You are victims of the oil reserves which are reported to have been discovered in your country.” Major M. F. Eden, who was deeply moved by the sight of Albanian patriots cast into the streets and forced to flee their country, said to them; “With my own eyes, I have seen the sacrifices you made to save your country in 1920, and my heart aches with you at the injustice you have suffered. Cursed be the day that they discovered oil in Albanian soil. The oil rigs may prove to be the graveyard of your national freedom.” The Bulgarian Likoff, for his part, who was sent to Brindisi to attract many of the Albanian patriots to his cause, set off for Vienna with Fan Noli, Kostandin Boshnjaku and several others, where the Comintern had its headquarters at the time. Many of those who followed him, in particular the young ones, continued on to Moscow, a move that marked the start of our current national tragedy.

The Konare [National Revolutionary Committee] was founded in Vienna, a revolutionary organisation with pro-communist leanings that left a very bad impression in moderate nationalist circles. The Albanian refugees all considered that it compromised them in international public opinion. The founding of this organisation confirmed to an extent the intrigues of the domestic and foreign enemies of Albanian democrats who accused us of communist inclinations in order to justify the plot they were hatching. As a reaction to the foundation of the Konare, a public meeting was held in Brindisi at which many patriotic emigrants took part. It continued for several days and led to the founding of the Bashkimi Kombëtar [National Unity] that, historically, can be considered as the successor to the Mbrojtja Kombëtare [The National Defence] and as a forerunner of Balli Kombëtar [The National Front], because they had the same goals and objectives.

In the early months of emigration, Luigj Gurakuqi was murdered in Bari by a cohort of the regime in power. This murder was one of the gravest mistakes made by the Albanian dictatorship, politically, morally and psychologically, because Gurakuqi was the only leader who could have served as a bridge between the Albanian emigrants and the regime that had attained power by means of an international plot. He had actually been against the June Revolution that was imposed on the country by the extremists. The murder of Gurakuqi gave great impetus to the nationalist movement abroad and damaged the reputation of the regime in power.

The Trani Court Case and its Repercussions, Italo-Yugoslav Rivalry and Greek Disillusion in Albania, England Gains Nothing from the Plot it Hatched.

Mussolini, who on two or three occasions declared that we had broken into tears when Giolitta-Sforza decided to withdraw Italian forces from Vlora in 1920, regarded the establishment of a dictatorship in Albania as a good opportunity to attain his objectives. The realisation of his policies began with the Trani court case when, after receiving orders from Rome, the court declared Gurakuqi’s assassin to be innocent and branded Gurakuqi, who was in fact a great supporter of Italy and a leader of the Catholic community in Albania, as a dangerous figure with communist leanings. With flattery and favours, and with threats and corruption, fascism managed to impose a “loan” upon the government in Tirana, a golden chain with which the head and feet of the Albanian people were bound. They were enslaved in particular by the concession for the so-called “national” bank. The final elements of the fascist yoke imposed upon our country were the Commercial Treaty and the other political and military agreements.

Yugoslavia also gained concessions from the new regime, initially by changes in the border, at Saint Naum and Vermosh. In addition to this, from the start, it gained a substantial political presence when Ceno Bey Kryeziu, one of its faithfuls, was made Albanian ambassador, when other figures were appointed to important posts, and in particular when the national army which had taken part in the June Revolution was replaced by a type of irregular militia headed by mercenaries of the Belgrade government and forces under the command of Wrangel officers.

The Belgrade government was, nonetheless, not too happy about the situation that arose because it was unable to stifle the rising influence of its fascist rival. The Albanian regime believed that it had deceived the people and the outside world with its neutrality and independence. At the same time, it was handing out concessions, to the country’s detriment, to Yugoslavia and to fascist Italy. Our closest neighbour, Greece, weakened and weary by the war in Anatolia, was unable to gain any particular advantage from the new regime, even with its army and government. The same went for Great Britain which, in international politics, had played the major role in imposing the dictatorship upon Albania, hoping thereby to gain access to all of Albania’s oil resources. However, it did not attain its objective because of strong opposition from fascist Italy. The Albanian oil fields in some regions were divided up among the Great Powers, despite all the quarrels that arose among them, as the general director in the Italian Foreign Ministry, Vincenzo Lojacono, admitted to me: “Siamo ai ferri corti con l’Inghilterra per la questione del petrolio in Albania.”

The Proposal of Baron Aloisi in Tirana, the Leghorn Meeting, the Dukagjin Uprising, the Pact of Tirana

Once he overcame the denunciations of Matteotti, Mussolini believed that he was the unquestioned lord of Italy. The first move in his imperialist policies was to get his hands on Albania, a country worn out and oppressed. Convinced from the state of the country at that time that the moment was ripe to take revenge for Drashovica, he appointed Baron Aloisi as his minister at the Italian Legation in Tirana. The baron had recently abandoned Bucharest after a scandal in his social surroundings. A week after his arrival in Tirana, Aloisi requested an audience with the President of the Republic, Ahmet Zogu, and casually, using subtle threats and inducements, proposed that Zogu come to the defence of fascist Italy and become a vassal of the Duce. Surprised at this outrageous offer, but keeping his calm, Zogu informed the minister of the Italian Legation that he would send him a reply in a few days. Once the ambassador left the office, Zogu contacted the English and French ministers in Albania and informed them of the proposal and the threats made by Baron Aloisi. When the British and French ambassadors paid a joint visit to Palazzo Chigi (using normal diplomatic channels) to seek an explanation for the stance of the Italian diplomatic representative in Tirana, Mussolini understood that he would not be able to attain his objectives without first seeking an agreement with the government in London and without British approval for what he intended to do in Albania. To this end, he began to prepare the diplomatic terrain and, a couple of months after Aloisi’s proposal, he organised a meeting with Chamberlain in Leghorn [Livorno]. Knowing that an agreement between two representatives of European imperialism could only be reached on the basis of the well-known principle of reciprocity, do ut des (“I give that you might give”), Mussolini, who wanted free hand to act in Albania, was aware that Chamberlain was interested in wresting the oil reserves in Mosul from Ataturk and in preserving English territorial concessions in China that were being challenged by Chiang Kai Shek. In return for a monopoly in Albania, Mussolini was pressed upon to promote British imperialist interests by making loud speeches on the Near and Middle East. Albanian oil in 1924 and Mesopotamian oil in 1926 were to be sources of national tragedy for the two countries in question. Our present tragedy can be interpreted in good measure as the result of our oil reserves.

After preparing the international terrain at the Leghorn meeting, Mussolini waited for an opportunity to carry out his plan to take over Albania. This opportunity was given to him by the Dukagjin Uprising. In early 1926, the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee, with its headquarters in Bari, was informed that demoralisation within the Albanian regime had reached a zenith because of corruption and the oppression of the population, and because of the concessions given to foreign circles in contradiction with vital national interests. Convinced that a well-organised movement could overthrow the regime without great sacrifice and would be welcomed by the majority of the population, the Committee made a corresponding proposal to Albanian patriots in the north and south of the country. The patriots in the south replied that they were ready to act unconditionally at the moment the Committee deemed suitable. The patriots in the north, for their part, asked for 5,000 gold Napoleons, a sum ten times greater than what the Committee had. A little later, however, the situation in the north changed radically and in the autumn of 1926, there was great support for an uprising in Albania, in particular after the proposal made by Baron Aloisi. At this time, the Catholic clergy and the leaders of the Muslim community in Shkodra informed the Committee that they were ready to organise an uprising without any financial backing. They added that the situation was so tense that, if the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee did not act, other irresponsible and ill-prepared individuals would take over leadership of a national uprising which, under such conditions, would have catastrophic repercussions for the country. Unfortunately this is exactly what happened. The Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee told patriots in Albania to make the necessary preparations, but to wait for orders before rising in revolt. The reason why the uprising did not begin immediately was a disagreement among the leaders of our organisation (Bashkimi Kombëtar) with regard to collaboration with Konare. Sotir Peci and the leaders of the north were strictly against any uprising conducted with Konare leaders because participation of the latter would compromise the movement internationally such that it would be decried as a communist revolt. The more moderate figures insisted that if they were to reject collaboration with Konare for reasons of political expediency, they should at least exempt Qazim Koculi and a number of other persons who were considered essential for the success of an uprising in the south of the country. After much discussion, the latter proposal was accepted and Koculi and his colleagues were invited from Vienna, where they were living, to come to Bari. While these discussions were underway, the above-mentioned meeting took place in Leghorn that resulted in the collapse of the revolt, as will be explained below.

After the death of Luigj Gurakuqi, Ali Këlcyra was sent to Rome as a representative of the Bashkimi Kombëtar organisation to seek contact with the competent Italian authorities and with foreign diplomats there. One of his principal objectives was to keep contact and inform the American Embassy about the course of events in Albania. One of the secretaries at the American Embassy was in regular contact with us and knew that a revolt was about to break out in Albania. A few days after the Leghorn meeting, this person phoned Ali Këlcyra’s brother, who was a student in Rome at the time, and left the following message: “As far as I understand, Mussolini has, on the basis of services rendered to Great Britain, been given free rein to act against Albanian independence. Palazzo Chigi is only waiting for an opportunity to act. Your brother informed me that plans were underway for an uprising in Albania. It is very likely, if a revolt breaks out over a widespread territory and lasts for some time, that the fascist government here would intervene or that the jeopardised regime would seek its support. This would have very negative consequences for your country. I would therefore advise you to inform Bari as quickly as possible and tell your brother and his friends to stop the uprising at least for the time being, until we can see more clearly what the Leghorn meeting has led to.” When it received this message, the Committee not only sent it on to all of its men in Albania, north and south, to stop all preparations for the revolt, but also informed the Albanian consul in Bari.

The Committee was also in contact with Xhavit Leskoviku who had arrived in Italy on a mission from Zogu to encourage Albanian emigrants to return to Albania because, based on secure information received, it looked as if fascism was preparing the international terrain to impose an Italian protectorate on the Albanian regime in power. To reassure the rulers in Tirana that there would be no interference from Albanian emigrants, the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee informed the Tirana regime, via Xhavit Leskoviku, that all of the prominent figures among the political refugees would be willing to leave Italy immediately if the consulate in Bari could issue them with travel documents. The documents were prepared but unfortunately, before everyone could be given a passport, the Dukagjin Uprising broke out. The Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee immediately contacted the Yugoslav consulate in Bari, via two of its members, Sotir Peci and Ali Këlcyra, who woke up Consul Vasa in the middle of the night and informed him as follows: “Although the Yugoslav government was a major factor in the international plot that led to our expulsion from Albania and to the reign of the treacherous dictatorship that is still in power, we are convinced that, in its own interests, it will not want Albania to become an Italian colony. On this issue, our interests correspond to yours. We therefore hasten to let you know that we have received information from secure sources that, at the Leghorn meeting, Mussolini was given free rein to act in Albania with a view to imposing a fascist protectorate on the country. We are informing you hereof in the hope that you will take appropriate steps in the international arena to counteract the common danger we are facing.” The Yugoslav consul assured us that he would inform his government immediately and ask for instructions. Two days later, he gave us Belgrade’s reply: “We admire the patriotism of the members of the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee and thank them for the important information received. However, this ministry is of the view that the information does not correspond to the truth. In view of the Treaty of Rapallo and the Nettuno Convention, the ministry does not believe that the government in Rome would take such a step in Albania, as this would be in complete violation of the spirit of these agreements.” From this reply, we realised that neither the government in Belgrade nor the French government were aware of the contents of the Leghorn agreement.

This was the first contact between Bashkimi Kombëtar and the Belgrade government. When the Pact of Tirana was announced, the Yugoslav consul asked for a meeting with the members of the Committee, during which he made it known that the Foreign Ministry in Belgrade had expressed its surprise about the precise nature of the information it had received from the Committee. Neither the Yugoslav government nor its allies had had any idea about the Committee. The consul announced that his superiors had instructed him officially to propose that we cooperate with the Belgrade government to stop fascist rule from taking root in Albania and to state that the Yugoslav government recognised the grave error it had made in its stance towards the patriots in 1924. This step marked the beginning of preparations for an agreement and cooperation between Bashkimi Kombëtar and the government in Belgrade, about which both the Konare and Çlirimtarja (i.e. the Çlirimi Nacional [National Liberation] organisation) trumped up much criticism, accusations and shameful fabrications. The Committee replied: “We take note, with regard to our official relations with the Yugoslav government, of the fact that it took an erroneous and unjust stance towards Albanian patriots in 1924. We hope that the damage done up to now will be a lesson for that government. Despite the disappointments of the past and present, the members of the Bashkimi Kombëtar organisation are willing to collaborate honestly with the government in Belgrade in order to save the country from the new imperialist forces threatening it. We hope from now on that the Yugoslav leaders will be inspired by the same goals, not only to defend their country and to liberate ours, but also to emancipate the Balkans and free it from the influence of foreign imperialists. However, we cannot conclude the agreement with the Belgrade government here, which is designed to counterbalance fascist imperialism in our country, since we are under observation by the Italian carabinieri day and night. We will endeavour as soon as possible to leave Italy and then, in Belgrade, we will be able to work out an action plan with the government there against the current regime which has become a tool of fascist imperialism.” Consul Vasa ensured the Committee on behalf of his government that Yugoslavia would provide all necessary support for Albania’s liberation. This statement was repeated to us more forcefully later, when we went to Belgrade, by the authorities there. Similar promises were made by all the Yugoslav foreign ministers after Ninčić. The extent to which these Yugoslav government officials kept their promises became clear with the policies of Stojadinović in the Pact of Belgrade in 1937 and in the position of the Yugoslav government towards the occupation of Albania on 7 April 1939.

The Failure of the Dukagjin Uprising

Despite all the important and sincere information we received from the secretary of the American Embassy, the little time we had at out disposal led to the failure of the uprising and possibly great hardship for the country. What both the Muslim and Catholic leaders of Shkodra feared, came to pass. They were afraid that, despite our warnings, the extreme tension in the country would cause it to explode into revolt, as indeed happened. Many of our compatriots who were political refugees, among whom were several Catholic officers and the priest Dom Loro Caka, lived in Montenegro and in other regions of Yugoslavia near the Albanian border. Estimating that the situation in the north of Albania was ripe for an uprising, and in an individualistic manner typical of Albanians, these persons, including Koço Tasi who had been summoned from Athens to this end, took the initiative upon themselves and called upon the movement to rise in revolt in these regions, without firstly consulting and warning the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee or the Konare or our patriots in the south. This revolt against the regime in Tirana had a certain religious, that is, Christian colouring to it, and one might say that some of the Yugoslav authorities in the areas along the border, while they may not have supported the revolt openly, encouraged it in order to force the Tirana government back into Belgrade’s lap. This support was another mistake made by the Yugoslav government because it did not hesitate to play these dangerous cards to the detriment of Albania, despite the warnings of Bashkimi Kombëtar that the Duce was plotting something at the international level. Later, when the Albanian patriots went to Belgrade to sign the agreement, the Yugoslav Foreign Ministry excused itself for the involvement by pretending that the encouragement offered to the Albanian rebels had been given by local administrative and military circles in the areas near the border that were not aware of the international ramifications.

Pursuant to the strict orders they received from the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee in Bari, the leaders of Shkodra, both Muslim and Catholic, did not give their support to the revolt set in motion by refugee Catholic officers. Indeed they did what they could to prevent it. For this reason, despite the marked success it achieved at the start, the uprising soon collapsed. The south of Albania, which had not even been informed about the revolt, did nothing, in line with instructions received from patriots abroad. […] Terrified by the initial success of the rebellion, although it was a very local movement, and cowering under the threats of Baron Aloisi, the Tirana government gave way immediately and signed the Pact of Tirana (27 November 1926) which was valid for an initial five years, though it was later not extended. A year thereafter, it signed the so-called Treaty of Alliance (22 November 1927) which was valid for a twenty-year period.

The Effects of the Pact on Political Emigration

The Pact of Tirana had great international repercussions because it constituted the first step in the spread of fascist imperialism to the Balkans. In Belgrade its effect was like a bomb. The Yugoslav Foreign Minister Ninčić who had helped prepare for the dictatorship in our country, was forced to resign. Before he did so, he stated the following in an interview given to a correspondent of the French newspaper Le Matin: “Zogu once sat where you are sitting at the moment when I called him in to inform him that everything was ready and he could depart immediately to seize power triumphantly. After thanking me, Zogu asked what he could do for us in return for the great favour we were doing to him. At that moment, we could have asked for any concession. I told him that we wanted nothing, simply that he maintain his country’s independence.”

Of course, the Pact had major repercussions on Albanian political emigrants, too. The Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee made preparations to leave Italian territory where it had been working up to then, but the fascist authorities refused to allow it to depart. Immediately after the Pact was signed, the Albanian political emigrants were interned and placed under the watchful eye of the carabinieri day and night. Despite the many difficulties involved, they managed to leave Italy secretly. Initially, the Bashkimi Kombëtar leaders stayed for a short period in Belgrade, where, after much quarrelling, they came to an agreement with the Belgrade government, under which an action plan was to be prepared aimed at preventing the establishment of fascist imperialism in Albania. The Albanian emigrants encountered major impediments in Belgrade at this time from the influence of the Albanian Minister, Ceno Bey Kryeziu, who was a close friend of the Yugoslav authorities. These authorities for their part were also interested in promoting secret cooperation between the Bashkimi Kombëtar leaders and Ceno Bey. The Albanian patriots categorically refused any such cooperation and were prepared to leave Belgrade if the Yugoslav government insisted on such ties, because they held the view that Ceno Bey was morally responsible for the murders of Bajram Curri and Luigj Gurakuqi and because, while he was Minister of the Interior, he had exercised unparalleled brutality in persecuting the representatives of the Revolution of 1924 who had remained in the country. An agreement was only reached after the departure of Ceno Bey from Belgrade during the Djurasković crisis when diplomatic relations between Albania and Yugoslavia were temporarily broken off. The heads of the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee then chose Vienna as their headquarters. Also located in Vienna was the Konare which, when the Pact of Tirana was made public, transformed itself into the Çlirimi Nacional [National Liberation] organisation that was openly pro-communist. Some of the leaders of the earlier organisation, such as Qazim Koculi, Kol Tromara, Aziz Çami and others, joined the Bashkimi Kombëtar organization. Bashkimi Kombëtar remained in the Austrian capital until 1931 when the assassination attempt was carried out on King Zog.

The Struggle between the Patriots and the Regime within the Country and Abroad

It is not unknown in many countries of the world for the opposition to carry out assassination attempts on those in power in their country, but it is a rare occurrence to see a regime systematically organise attempts on the lives of the opposition, in particular when they are refugees abroad. But this is what the regime in Tirana did, much like the Soviets before it. After the assassination of Gurakuqi, an attack was carried out on Shefqet Korça in Brindisi. This refugee miraculously survived the bullets of the assassin (of the Tirana regime). The trial of the would-be assassin in Lecce proved to be a scandal for the Albanian government, even though it was held after the Pact of Tirana when the fascist authorities were giving their full support to the Albanian regime they were protecting.

In May 1929, Ali Këlcyra, a member of the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee and editor of its journal, was forced to leave Austria under pressure exerted on the Austrian government by the Italian Legation. In Athens, an assassination attempt was carried out on him while he was strolling through Zappion Park with Koço Tasi. Tasi received four light wounds. After this, Ali Këlcyra was obliged to leave Greece and take up residence in Paris, as a delegate of the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee, where he resumed publication of its journal.

In February 1931, Zog set off for a visit to Vienna where various Albanian political emigrants were living, who considered his visit a provocation and an offence to their dignity. For this reason, all the emigrant groups, despite their differences, joined forces to prepare an attempt to assassinate the king. Many of the patriots from various European countries endeavoured to travel to Vienna to take part in the action, but they were unable to get there because of visa problems. At this time, Albanian emigration was divided into three groups:

(a) the Bashkimi Kombëtar organisation, supported by Yugoslavia and its allies;

(b) the Çlirimi Nacional organisation that collaborated with the Comintern;

(c) pro-Italian groupings who, although they were foes of the Tirana regime, were supported by the fascist authorities.The pro-Italian group, led by Hasan Prishtina, Mustafa Kruja and Qazim Mulleti, not only took part in the plot against Zog, but actually played the major role in it. They were the ones who informed Ndok Gjeloshi that Zog would be at the Vienna Opera on the evening in question. There are many indications with regard to this plot that some undercover fascist circles were not only aware of the assassination attempt, but actually encouraged it. The Yugoslav authorities, for their part, not only prevented the members of Bashkimi Kombëtar, called to take part in the plot, from getting to Vienna, but informed Tirana (this was later confirmed to us by Musa Juka in Egypt) about the plot while Zog was still in Albania, i.e. before he left for Vienna. All of this shows just how insincere the government in Rome was towards the Albanian regime and just how insincere the government in Belgrade was towards Bashkimi Kombëtar. Their real positions became more than apparent on 7 April 1939.

The grave of Ali bey Klissura

at the Protestant Cemetery in Rome

(Photo: Robert Elsie, March 2011).

In 1932 preparations for a revolt in Vlora were uncovered. The preparations had been carried out with the knowledge of the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee in Vienna and with the collaboration of the Yugoslav legate there. However, letters were also exchanged written in invisible ink so that the Yugoslav legate would not be able to read them. The revolt failed because it was betrayed by Idriz Jazo (Kuçi). Steps undertaken by the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee and the arrival in Albania of the one-time Russian naval minister Lebedef, of whom we have spoken earlier, enabled us to save the lives of many of those who were sentenced to death. But the failure of this revolt did not in any way demoralise the nationalists and the Albanian people, who despised the regime in power. In the autumn of 1934, the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee in Paris received information from various sources in Albania that a new revolt was being prepared and was to break out in several months’ time in Fier. Strangely enough, the regime in power, despite its well-organised secret service, learned nothing of this until the last moment. Musa Juka later told us in Alexandria that they were only informed of the uprising by Teki Xhindi when Riza Cerova was preparing to leave for Berat. Our foreign affairs committees did not contribute to this revolt at all because our representatives in Albania had repeatedly begged us not to get mixed up in it, in particular since the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee was collaborating with the Belgrade government, such that we would have given rise to suspicion in Rome that the revolt was being supported by Yugoslavia. This would have brought about immediate Italian intervention to quell the uprising from the start. All the political currents in the country took part in the attempted revolt of Vlora and in the Fier uprising of 1935: democratic nationalists, communists and pro-fascist groups. On the basis of the information we received, nonetheless, we were convinced that the fascist authorities were aware of this uprising, and it is eminently possible that they were encouraging it, and perhaps even assisting it. The new revolt, prepared on a broad basis, could have been successful if it had been prepared well. It is, however, an undeniable fact that the presence of Riza Cerova and a few other extremists frightened off the beys and large landowners, causing them to withdraw from the initiative at the last moment. This enabled the regime, despised by Albanians of all classes and political affiliations, to survive miraculously. With regard to this revolt, Musa Juka later informed me in Egypt: “When the uprising broke out, we did not know whom we could trust at all.”

When the rebels in Fier were being tried in court, a campaign initiated by the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee at the League of Nations in Geneva managed to save the lives of dozens of innocent opponents of the regime who had been incarcerated. This fact, known by everyone, was even acknowledged by the officials of the regime when they were later in exile in Alexandria.

It is quite likely that the Toto movement of 1936 was also secretly instigated by certain fascist circles endeavouring to free Albania from Italian tutelage. The Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee in Paris had no information about this movement and was taken by surprise by it.

The fight against our patriotic refugees continued outside of Albania. Hasan Prishtina was assassinated in Salonica by an emissary of the Tirana government. The assassin, who stemmed from the Ohrid region and who lived on the French Riviera, had been recommended to Hasan Prishtina by Irfan Ohri at a time when the former was living in France. Hasan Prishtina had persuaded the assassin to go and kill Zog, but when he got to Tirana the assassin changed his mind and, induced by Musa Juka in collaboration with the Yugoslav Legation, he returned to Salonica and killed Hasan Prishtina instead. Not only did the assassin receive money from representatives of the regime, but he also got a promise from the Yugoslav Legation that he would be given a plot of land in the village where his family lived.

In March 1936, the leaders of Albanian emigration held a meeting in which the representatives of the three major groups took part, as well as younger men who had left Albania after the Fier revolt. At this meeting, stock was taken of the domestic situation and of the situation of Albanian emigration in general. Çlirimi Nacional had few members left when Zai Fundo [Llazar Fundo] asked for permission to return to Albania. However, just as it had in 1925, when the regime issued a general amnesty, the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee insisted on a continuation of the struggle, despite the vociferous propaganda of Mehdi Frashëri, who had risen to power once again (1935-1936) and called for Albanian emigrants to return to the country. The participants all rejected Mustafa Kruja’s proposal to put an end to the struggle, etc.

It ought to be noted that throughout the emigration period (1924-1939), the Bashkimi Kombëtar Committee and I myself did nothing to impede direct contacts with the Çlirimi Nacional people and to negotiate with them in a fraternal spirit in order to see how we could best serve the country’s interests. This became impossible in Albanian emigration circles after 1944. […].

[Extract from the political memoirs of Ali Këlcyra, published in: Ali Këlcyra - Shkrime për Historinë e Shqipërisë, edited by Tanush Frashëri (Tirana: Onufri 2012), pp. 107-140. Note that some quotations in this text, originally in English, have been retranslated from the Albanian version. Translated from the Albanian by Robert Elsie.]

TOP