| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

1999

The Hague Tribunal (ICTY):

The Victims of Vushtrria

Serbian paramilitary forces entered the town of Vushtria (Vučitrn) in northern Kosovo in late March 1999. The following account, based on eyewitness testimony given at The Hague Tribunal, is taken from the 2011 Judgement of Vlastimir Đorđević and reveals the grim nature of the events that took place there and in the surrounding region.

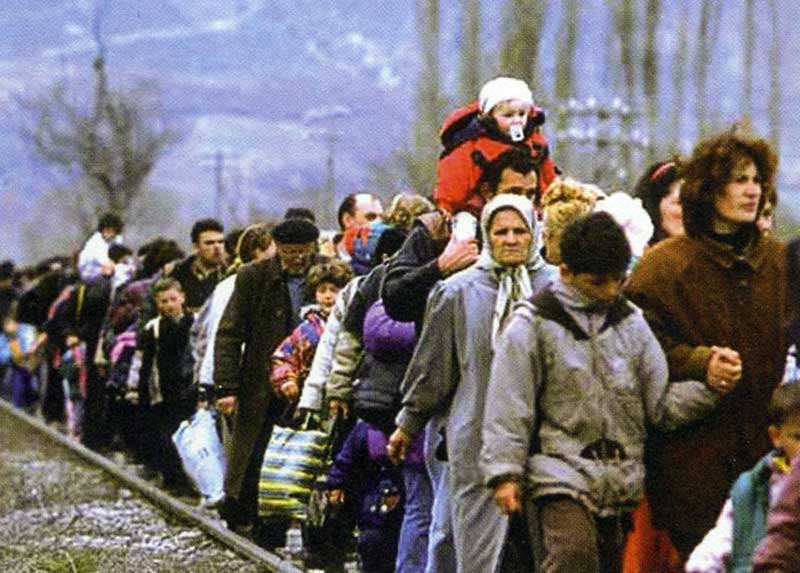

Kosovo Albanian refugees fleeing their country in March 1999.

Vučitrn/Vushtrri town

1. On 27 March 1999, Serbian forces, some wearing blue camouflage uniforms and others green camouflage uniforms, arrived at a school in Vučitrn/Vushtrri town. A witness, Sabit Kadriu, observed two Serbs wearing civilian clothes entering a house opposite the school. Shortly thereafter, he saw this house and the neighbouring house burning. The witness also observed Serbian forces wearing green camouflage uniforms in the vicinity of the burning houses.

2. The same day in the evening, the old part of Vučitrn/Vushtrri and the town centre were burnt. The minaret of a 17th century mosque located in the town centre was burnt and fell down. The surrounding buildings belonging to the mosque were also burnt. Shouting and the sound of doors being broken could be heard. On 28 March 1999, in the morning, shooting was heard in the town. On 29 March 1999 in the morning, three or four bodies were found on a street nearby the old Vučitrn/Vushtrri Bridge.

3. Evidence confirms that at the time, blue camouflage uniforms were worn by police and that green camouflage uniforms were worn by the VJ and the PJP of the MUP. The presence of MUP and VJ forces in Vučitrn/Vushtrri town is supported by an order issued by the Military District Command and dated 27 March 1999, redeploying the 54 Military Territorial Detachment of the Priština/Prishtinë Military Sector to Vučitrn/Vushtrri town. This order tasked the VJ units to act, in coordination with MUP forces, to establish control of the Vučitrn/Vushtrri area. Another document indicates the presence of two platoons of the 3rd Company of the PJP in Vučitrn/Vushtrri municipality at the time.

4. On 1 April 1999 at around 0840 hours, people in Vučitrn/Vushtrri town heard voices shouting and telling the people to leave. These voices were those of police who were wearing blue camouflage uniforms. The residents were told to go to the cemetery. Three policemen were telling residents to be quick and Sabit Kadriu recognized one of the policemen to be Dragan Petrović, the Commander of Vushtrri/Vučitrn police station. He also saw a policeman beat, with the butt of his gun, a man who refused to leave his home.

5. When the people of Vučitrn/Vushtrri town arrived at the cemetery, there were no Serbian forces present. However, three buses from the private company Hajra were waiting, as they had been instructed by the police. A bus-driver told the people that the police had instructed him to take them to FYROM. Most of the people at the cemetery boarded the buses, but because of a lack of space, some people had to walk behind. Sabit Kadriu did not board the bus and was able to reach the house of the KLA commander in Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme. This house was full of people who had left their villages. On 2 April 1999, Sabit Kadriu moved on to Cecelija/Ceceli, which was under KLA control.

Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm

6. The village of Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm is situated on a plain in the municipality of Vučitrn/Vushtrri. The neighbouring village of Gornji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Epërm, is located on an elevated area north of Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm. In March 1999, there were approximately 80 Albanian households and 10 Serbian households in the lower part of Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm. The village of Gornji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Epërm is visible to the naked eye from Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm.

7. In March 1999, VJ forces had taken position in the neighbourhood of Llapzoviq in the village of Samodreža/Samodrezhë and in the hills of Gornji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Epërm, on the Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme side.

8. On 27 March 1999, all the Serbian families left Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm for the village of Nedakovac/Nedakofc. On the next day, Fedrije Xhafa, an Albanian resident of lower Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm, heard heavy weapon fire and observed that the houses in Gornji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Epërm were burning. Because of the events and fearing for their safety, with only a few exceptions, all Albanian families left Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm in a convoy. The convoy travelled through the village of Gornja Dubnica/Dumnicë-e-Epërme and Samodreža/Samodrezhë, before stopping in Vesekovce/Vesekoc. Fedrije Xhafa’s father, her uncle and her cousin, who had remained in Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm, were nevertheless forced to leave the village shortly after the convoy because of danger to the Kosovo Albanian people from sniper shots coming from the direction of Nedakovac/Nedakofc. The Albanian families were not allowed to return to the village at this time.

9. At the end of the war, when the residents of Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm were able to return to the village, they found that the houses belonging to Albanian families were burnt and that the houses of Serbian families were not damaged.

Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme and Slakovce/Sllakoc

10. The village of Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme is divided into the neighbourhood of Lower Mohalla and the neighbourhood of Upper Mohalla. Upper Mohalla is also known as Rašica/Rashica. It is situated on an elevated area of Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme. On 28 and 29 March 1999, Serbian forces were present in Donji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Poshtëm and in Rašica/Rashica. Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme came under Serbian shelling and other weapon fire, causing the population to flee towards the surrounding hills. On 29 March 1999, Serbian forces, believed to be local Vučitrn/Vushtrri police, came to Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme and told the residents they had 15 minutes to leave the village or face the consequences. Villagers then fled to the hills surrounding the village. The lower part of Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme came under small arms fire, while Rašica/Rashica was under shelling from VJ tanks and heavy weapons. During this operation, houses in the village were set on fire. A witness in the hills observed that Serbian forces stayed in Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme for a few days.

11. Between 7 April 1999 and 10 April 1999, Shukri Gërxhaliu was in his house in Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme. Around 10 April 1999, he heard that Serbian forces were coming to take him away. Fearing for his safety, he hid in bushes at the back of his house. While hiding, he heard men asking his wife in Serbian and in Albanian about his whereabouts. He was told later by his wife that the men were police officers. Later, he observed that the house of Izet Bunjaku, in Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme, was burning. Because of this incident, the witness left the village with his family to go to a KLA controlled area in the surrounding hills. On the way, as they walked by the stream running alongside the road towards Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme, the family came under small arms fire but were not hit. When they came within sight of Rašica/Rashica, they were also shelled by VJ tanks. As the family reached a strip of land between 200 and 300 metres in length, located between KLA and Serbian controlled territory between Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme and Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme, they were picked up by people in a horse and cart and taken to Slakovce/Sllakoc, where KLA forces were located.

12. Up until the end of April 1999, the KLA resisted Serbian forces in Vučitrn/Vushtrri municipality. However, around 28 April 1999, Serbian forces successfully advancing against KLA positions in the mountains in the direction of Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovicë, took control of Bajgora/Bajgorë, and established a camp at Bare. A simultaneous offensive by Serbian forces was launched from the direction of Podujevo/Podujevë and Serbia. On 1 May 1999, Serbian forces advanced to Vesekovce/Vesekoc.

13. Around 28 April 1999, an advance by Serbian forces in the area caused displaced Kosovo Albanians sheltering in the mountainous region Shala to move towards Samodreža/Samodrezhë, Slakovce/Sllakoc and Cecelija/Ceceli.

14. An order dated 15 April 1999 from the Joint Command indicates that the VJ Pri{tina/Prishtinë Corps was deployed at this time to support MUP forces in “breaking up and destroying KLA forces in the Shala Zone, including in Samodreža/Samodrezhë and Cecelija/Ceceli.

15. On 1 May 1999, Serbian forces advanced to Vesekovce/Vesekoc, a village situated in the north-east part of Vučitrn/Vushtrri municipality. In the evening of the same day, Serbian forces started shelling Vesekovce/Vesekoc.

16. On or around that day, in the village of Slakovce/Sllakoc, located south of Vesekovce/Vesekoc, the KLA was resisting the advance of Serbian forces coming from the village of Meljenica/Melenicë and from the Llap Zone. The KLA told the people in Slakovce/Sllakoc that they were running out of ammunition to defend Slakovce/Sllakoc and told them to go to Vučitrn/Vushtrri town. Meanwhile, the KLA moved from Slakovce/Sllakoc to the east and Serbian forces started shelling Slakovce/Sllakoc.

17. On 2 May 1999, by 1100 hours, Slakovce/Sllakoc was being shelled heavily. Houses were seen burning and the sound of automatic gunfire was heard. Shortly thereafter, Serbian infantry forces entered Slakovce/Sllakoc. At around 1300 hours, over 30,000 Kosovo Albanian people left Slakovce/Sllakofc on foot, by horses and by vehicle.

18. The convoy first travelled to Cecelija/Ceceli before heading towards Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme, Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme and Vučitrn/Vushtrri town. The road between Slakovce/Sllakoc and Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme was approximately seven kilometres long. Between Cecelija/Ceceli and Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme, the convoy came under VJ shelling and gun fire coming from Slakovce/Sllakoc, the Rašica/Rashica neighbourhood in Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme, Gornji Svračak/Sfaraçak-i-Epërm and from the north. At around 1500 hours, the shelling and gunfire forced the convoy to stop in Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme. At least two people in the convoy were wounded by gunfire.

19. Between 1600 hours and 1700 hours that same day, the convoy was able to start moving again. However, as the convoy progressed short bursts of machine gun fire were heard. At around 1800 hours, the convoy stopped in a position that was sheltered from the line of fire by a curve in the road. This was at a location some three kilometres past Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme and about one kilometre from Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme. Serbian forces had imposed a 1600 hours curfew in that area. At night fall, houses in Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme were seen to be burning and automatic gunfire was heard coming from that village.

20. At around 1700 hours, Serbian forces approached the convoy from the north in APC vehicles and Pinzgauers. They wore green camouflage uniforms, blue camouflage uniforms and plain black uniforms. Some wore bandannas. There were men with painted faces, others wore plastic masks which covered the area from their face to their chest with holes for the eyes and the mouth and were painted with eyebrows and moustaches. Serbian forces were described as paramilitary. There is other evidence that paramilitary forces wore plain black uniforms, bandannas, and had painted faces or wore masks. While the description of the Serbian forces in black uniforms is consistent with them being paramilitary forces, the presence of green camouflage and blue camouflage uniforms confirms, in the Chamber’s finding, that there were also MUP and VJ forces in the mixed Serbian forces which came to the convoy.

21. The Serbian forces demanded money from people in the convoy and they threatened to rape the wife of a witness if she did not pay. The witness’s wife then paid some money. The brother-in-law of this witness, Halil Basholli, was asked for his name and where he was from. He was then beaten by members of the Serbian forces with a rifle, wooden sticks and police batons. Halil Basholli was heavily injured as a result of the beating.

22. Another group of Serbian armed men, identified as policemen, driving Jeeps and APCs, approached the main body of the convoy that had remained on the road to Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme. The police came from the direction of the neighbourhood of Rašica/Rashica in Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme. They pushed a vehicle which was in their way into a stream nearby. They disembarked from their vehicles and demanded money from the people in the convoy, shooting men who did not pay. One witness saw Serbian forces approach one tractor and repeatedly ask the tractor-driver for money. He then saw police pull the driver off that tractor. The tractor-driver’s father, Sherif Bunjaku, begged the police not to kill his son. However, automatic gunfire followed and the tractor-driver was killed. The tractor driver was not armed. The Chamber accepts that the tractor driver was Hysni Bunjaku, a Kosovo Albanian who is listed in Schedule I of the Indictment and was 21 years old at the time of the events. Members of the Serbian forces were heard to say that they had killed about 50 people and that they would not stop until they reached 100.

23. At about the same time, Shukri Gërxhaliu, who was travelling in the convoy, heard men speaking Serbian approach the tractor of Haki Gërxhaliu and his family, which was immediately behind Shukri Gërxhaliu’s trailer. Haki Gërxhaliu got off his tractor and he was shot. Shortly after, fearing for his life, Shukri Gërxhaliu jumped off his trailer to run away. As he did, he landed on top of the body of Haki Gërxhaliu, who was lying on the ground next to his tractor, apparently dead. Several other members of the Gërxhaliu’s family who were in the convoy were shot that night, although the evidence does not enable them to be separately identified. Tractors belonging to people in the convoy were pushed into the stream or burnt by members of the Serbian forces.

24. Later that evening, at around 2100 hours, three men from the Serbian forces wearing uniforms and masks and carrying automatic weapons, arrived from the direction of Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërme and went to another part of the same convoy. They ordered the people in that part of the convoy to move towards Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme. As the convoy continued its route, members of the Serbian forces pointed a search-light on a man in the convoy. Automatic gunfire was then heard from this location and the body of a man from the convoy was seen to be lying on the ground. Members of the Serbian forces who had fired at this man were standing next to his dead body. The dead man was not armed.

25. After 2100 hours, the convoy arrived at a fork in the road. One of the roads led to Vučitrn/Vushtrri and the other led to Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme. Serbian forces directed the convoy to the Vučitrn/Vushtrri road. Meanwhile, shells fell approximately 50 metres from the convoy and divided it in two. While the main part of the convoy stayed in the area of Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme, a smaller part of approximately 1,000 people was directed by Serbian forces to continue to Vučitrn/Vushtrri. This segment of the convoy arrived at the Agricultural Cooperative in Vučitrn/Vushtrri at about 2200 hours.

26. Later that evening, the sound of gunfire was heard in the convoy. Combined Serbian forces, coming from the north in green APCs and Pinzgauers covered with branches, surrounded the convoy. Some members of the Serbian forces wore blue camouflage uniform, others wore plain black uniforms and the remainder wore green camouflage uniforms.

27. The people in the convoy were ordered to clear the road to let the police and VJ vehicles pass through. Shortly after, a large group of Serbian police officers fired their machine guns in the air. They cursed and shouted insults in Serbian at people in the convoy. They examined the identification documents of a man called Ismet and accused him of being a KLA fighter. Some evidence does indicate that Ismet had been a member of the KLA in the past, but not at the time he was in the convoy. He was not armed. Ismet was beaten with bare hands and threatened that he would be killed unless he paid money. The policemen were given money after which Ismet was released.

28. One member of the Serbian forces wearing a green sleeveless vest over a dark blue camouflage uniform, in the Chamber’s finding, a policeman, pulled Fedrije Xhafa’s brother, Jetish, from his tractor and beat him with a thick wooden stick. The policeman then threatened to kill Jetish Xhafa unless he paid money. A woman gave the policeman her jewellery and Jetish was released.

29. Shortly after this, at about 2330 hours, another group of men approached Jetish Xhafa’s tractor. The men wore blue police uniforms and two of them had black gloves, black balaclava masks with holes for the eyes and mouth with their blue camouflage uniforms. The uniforms satisfy the Chamber that these were police. One of the policemen pointed a machine gun at Fedrije Xhafa’s mother. Meanwhile, Jetish was dragged to a nearby road facing towards Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme. A policeman pointed his rifle at Jetish’s head. A single shot was fired and Jetish fell to the ground. The policemen then dragged Fedrije Xhafa’s father to the spot where Jetish lay. Fedrije Xhafa heard shots. After the second shot she heard her father, Miran Xhafa (71 years old) cry out. She heard a third shot and she saw that her father had fallen to the ground. Not long after she heard another shot. It was not until after the war that Fedrije Xhafa learned that Jetish had survived but that her father had died in this incident. Neither of the men shot had been armed.

30. At about the same time as these events, Fedrije Xhafa’s family, still in the convoy, was ordered by Serbian forces to start moving. The convoy was again under way. There was nobody left in the family to drive the tractor. Lavdim, who was 13 years old and who did not know how to drive, attempted to move the vehicle but was beaten by a policeman with the butt of his rifle when he failed to make it move. After a few attempts, Lavdim was able to move the tractor for approximately 100 metres but then stopped on the side of the road. The family then hid behind the tractor. The family sent one of its members, Ismet, to Samodreža/Samodrezhë to tell KLA forces what had happened to the convoy. Other Serbian police wearing blue camouflage uniforms returned to the tractor and ordered the family to keep moving with the rest of the convoy. The family left the tractor and their belongings behind as there was no driver and continued in the convoy on foot. As the convoy progressed, Serbian forces ordered the people in the convoy to shout: “KLA”, “Slobo” and “Draza”. On the way, a witness observed seven or eight corpses. Amongst them, she recognized her cousin, Veli Xhafa, who lay dead on his tractor. The witness also observed injured people, including women and children, on the road. One of them, a young boy, was shot by a policeman.

31. Shukri Gërxhaliu, who was in another part of the convoy, observed that 10 vehicles carrying soldiers and police, coming from the direction of Vučitrn/Vushtrri town, were heading along the road from Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme to Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërm. These were APC vehicles and three regular police cars. One of the occupants, a VJ soldier, was heard to say that the area had been “mopped up”. The vehicles carrying the soldiers and police moved on, and the convoy was able to keep going. Bodies could be seen on both sides of the road as they moved along. One witness left the convoy and return to Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërm. There, he found KLA soldiers burying human corpses. Many appeared to have been shot from a close range. The victims were mostly men but there were some women and children. A KLA member showed the witness a list of 97 people believed to have been killed and asked if he knew any of them. The witness’s name mistakenly appeared on the list and was crossed out.

32. The Defence challenged the credibility of Shukri Gërxhaliu, arguing that in his previous testimony before the Tribunal, he did not mention the presence of policemen in the vehicles that came from Vučitrn/Vushtrri. The Chamber notes that Gërxhaliu had amended his previous statement to include that, in addition to the soldiers, policemen were in the APC vehicles and the police cars that came from Vučitrn/Vushtrri town. The Chamber does not consider that this amendment undermines Gërxhaliu’s credibility. Although Gërxhaliu was a member of the KLA at the time of the event alleged in the Indictment, and for this reason his evidence has been considered with much care, the Chamber was generally impressed by the witness and considered that he gave credible and reliable evidence about events in the municipality.

33. Later that day, it was seen from the convoy that the village of Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërm was burning. At about 0200 hours on 3 May 1999, the main part of the convoy, still escorted by Serbian forces, rejoined the smaller segment of the convoy that had reached the Agricultural Cooperative in Vučitrn/Vushtrri.

34. It is alleged in the Indictment that during the night of 2/3 May 1999, Serbian forces killed approximately 105 people travelling in a convoy on the “Studime Gorge” road, in the direction of Vučitrn/Vushtrri. Schedule I of the Indictment lists 104 alleged victims by name.

35. As discussed above, eye-witness evidence establishes that four of the victims listed in the Indictment, Hysni Bunjaku, Haki Gërxhaliu, Miran Xhafa and Veli Xhafa, were killed by Serbian forces in the night of 2/3 May 1999 on their way to Vučitrn/Vushtrri town. The evidence about the killings of Haki Gërxhaliu, Miran Xhafa and Veli Xhafa is supported by the findings of the French forensic experts who later exhumed and examined the bodies. The forensic reports reveal that they had suffered a violent death caused by gunshot wounds to the head. The body of Hysni Bunjaku was never found by the forensic team. However, based on eye-witness evidence, the Chamber is satisfied that he was shot and killed in the convoy by Serbian forces in the night of 2/3 May 1999. Based on the eyewitness account discussed above, the Chamber is satisfied that at the time of their killing, these victims were travelling in a convoy of displaced people, were in the custody of Serbian forces and were not taking active part in hostilities. The Chamber is satisfied that these victims were Kosovo Albanians.

36. With respect to the remaining men listed in Schedule I of the Indictment, no evidence about the circumstances of their death has been presented. The Prosecution seeks to rely on the evidence of Sabit Kadriu, the President of the local War Crime Commission of Vučitrn/Vushtrri, who investigated the killings of the people in the night of 2/3 May 1999. It is his evidence that on the basis of interviews he conducted with the families of the victims and eye-witnesses, he compiled a list of 104 victims thought to have been killed on 2/3 May 1999, in various locations in Vučitrn/Vushtrri municipality. Kadriu’s list is identical to the list in Schedule I of the Indictment. It is also Sabit Kadriu’s evidence that the bodies of these 104 persons were found on 3 May 1999, and were then buried in a cemetery in the village of Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërm.

37. Considering its finding that, at the time, there was on-going fighting between the KLA and Serbian forces in Vučitrn/Vushtrri municipality, the Chamber cannot exclude the possibility that some of the men buried in the cemetery in Gornja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Epërm may have been killed while taking part in hostilities or that their death may not have been caused by Serbian forces. The Chamber is not satisfied that the remaining persons listed on Sabit Kadriu’s list were killed by Serbian forces in the manner described above.

Agricultural Cooperative in Vučitrn/Vushtrri town

38. The policeman who had beaten Jetish Xhafa during the progress of the convoy to Vučitrn/Vushtrri town was at the Agricultural Cooperative in the town. Policemen in blue uniforms ordered people from the convoy to go to various buildings of the Agricultural Cooperative, which was a government owned facility with large storage hangars, located on the outskirts of Vučitrn/Vushtrri town.

39. The people from the convoy spent the night of 3 May 1999 inside the buildings of the Agricultural Cooperative. The buildings were dark and crowded. Police guarded the compound and stopped people from going out to get water.

40. On 4 May 1999 in the morning, the people were ordered out of the buildings. Police had surrounded the buildings area. Sabit Kadriu heard people discussing the killings on 2 May 1999. He observed that some people in the convoy had carried in their tractors the bodies of their relatives who had died on way to Vučitrn/Vushtrri. The witness recognized the bodies of a mother and her two sons from the village of Pasoma/Pasomë. The evidence indicates that between 17 and 29 bodies were seen on the road to the Agricultural Cooperative in Vučitrn/Vushtrri.

41. At around 1300 hours, a man understood to be Simić, the deputy police commander of Vučitrn/Vushtrri, arrived on the site of the Agricultural Cooperative buildings. He too wore a blue police camouflage uniform. Shortly after, police proceeded to separate men aged approximately 15 to 73 years old from their families and took them to a nearby field which was surrounded by police. In the field, Serbian forces checked the men’s identification documents. A man understood to be Dragan Petrović was supervising this operation.

42. Meanwhile, two policemen instructed one of the Kosovo Albanian men from the convoy, Ali Menica, to come with them out of the Agricultural Cooperative buildings. The two policemen took Ali Mernica to the gate of a factory across a main road. One of these policemen waited at the gate, while the other took Ali Mernica inside the premises. Immediately after, two gunshots were heard inside the premises. Ali Mernica was unarmed and in custody of armed police when taken inside the premises as described above. After the war, a witness heard that the body of Ali Mernica was buried in the village of Pestovo/Pestovë. However, his body was never found by the forensic teams who conducted crime scene investigations and forensic examinations. In these circumstances, the Chamber cannot be satisfied by the evidence that his death has been established.

43. At about 1330 hours, civilian trucks with long trailers and an excavator were brought to the field. Approximately 30 men who had driving licences were singled out from the group and sent back to the Agricultural Cooperative buildings. Other men who paid money to Serbian guards were also allowed to go back. The remaining men in the field were ordered to get in the trucks. Police formed a line and beat the men with wooden sticks as they ran towards the trucks. The trucks drove the men to Smrekovnica/Smrekonicë prison, situated approximately halfway between Vučitrn/Vushtrri and Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovicë.

44. Meanwhile, police ordered the remaining persons from the convoy, mainly women and children, to get a registration certificate at one of three offices that had been set up in the Agricultural Cooperative buildings.

45. Afterwards, Simić ordered the people from the convoy to leave Vučitrn/Vushtrri town. He ordered those who had tractors to drive to Albania and those who were on foot to walk back to Smrekovnica/Smrekonicë or Dobra Luka/Dobërllukë. Fedrije Xhafa’s family did as they were ordered. Xhafa’s mother, who was sick, was put on another tractor and driven to Albania while the rest of the family walked to the village of Kicić/Kiciq where they found shelter in an empty house. On 7 March 1999, the family went to Dobra Luka/Dobërllukë, where they stayed until approximately 30 June 1999.

46. The Defence argues that the movements of population were voluntary and that they were not the result of forced expulsions by Serbian forces. In support of its contention, the Defence puts forward that Xhafa’s family first went to Kicik/Kiciq and then to Dobra Luka/Dobërllukë where they remained until NATO troops arrived. Shukri Gërxhaliu and his family, returned from the Agricultural Cooperative to their homes in the village of Donja Sudimlja/Studime-e-Poshtme.

47. The evidence satisfies the Chamber that the people left Vučitrn/Vushtrri town by virtue of the actions of the Serbian police, not of their free will. Under the direction of the Serbian police, they were deported to Albania or displaced to Smrekovnica/Smrekonicë and Dobra Luka/Dobërllukë. This will be discussed in further detail later in this Judgement.

Smrekovnica/Smrekonicë prison48. The men sent in trucks from the Agricultural Cooperative to the Smrekovnica/Smrekonicë prison had their identification documents checked on their arrival at the prison. This was done by persons wearing civilian clothes, who were thought to be secret police. A witness recognised Duško Janić, chief of the secret police in Vučitrn/Vushtrri, and the deputy police commander, Simić, who were supervising the registration.

49. As they walked inside the prison, the detainees were ordered to hold their hands behind their necks and they were beaten with sticks and guns by police. Sabit Kadriu was locked up in a cell, along with approximately 63 other men, for approximately 20 days. The cell was very crowded. There was no space to sit or lie down. Some of the men were kept in the prison’s corridors. During their first two days of detention, the men were not given any food. On the third day, they were given water and bread. The water was dirty and most men became sick. A man who asked for medication was taken outside and he was heard screaming. After the third day of detention, every evening, the men were taken to a dining hall to eat. On their way there and back, they were beaten with sticks by policemen.

50. Around 17 May 1999, after 12 or 14 days of detention, the detainees were taken to the office of the prison’s supervisor. On their way they were beaten with sticks. They were taken inside the supervisor’s office in groups of two or three. Two Serbian men wearing civilian clothes questioned them. One witness described his experience of this questioning. He was asked whether he was a member of the KLA and was then forced to sign a confession that he belonged to group of terrorists acting against the Serbian government.

51. The following day, around 18 May 1999, men from the convoy were taken in groups of seven or eight to the basement of a small building located in the prison’s yard by policemen wearing blue camouflage uniforms. The Chamber is satisfied that these policemen were members of the regular MUP. Other groups of detainees were taken by prison guards. Soon after the detainees had entered the basement, screams were heard. This became a usual occurrence. Detainees were taken to the basement on a daily basis and then screams were heard from the basement. On one occasion, a detainee was heard to be screaming from the basement and then, police came back up the stairs, without the detainee. One of the policemen present was identified as Saša Manojlović. He wore a green camouflage uniform. Based on the evidence dealing with uniforms discussed earlier, the Chamber is satisfied that this man was a member of the SAJ of the MUP, who acted in coordination with local police in this operation. The following morning, a policeman brought three or four men, also thought to be police, and one man in civilian clothes to the prison yard. Shortly after, four policemen came out of the basement, carrying a body concealed under a blanket.

52. A few days later, half of the detainees from the convoy were taken to a technical school by policemen. There, the men were made to kneel down with their hands up and three or four policemen beat them with sticks. Other policemen then took over and the beatings continued. Later, some civilians were brought in and they beat the prisoners with iron bars. The men were questioned individually about their ties to the KLA and to the OSCE. The other half of the men were taken to the medical school in Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovicë town. When they were brought back to the prison, at approximately 1500 hours that day, both groups of men (those from the technical school and those from the medical school) were covered in blood.

[Excerpt from: International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991 (ICTY). Public Judgement with Confidential Annex. Prosecutor v. Vlastimir Đorđević. 23 February 2011. Paragraphs 1163-1214 (here without footnotes).]

TOP