| | Robert Elsie | AL Art | AL History | AL Language | AL Literature | AL Photography | Contact | |

Robert Elsie

Texts and Documents of Albanian History

BACK | AL History

Kolec Topalli

(Photo: Robert Elsie, August 2003)

2010

Kolec Topalli:

Communist Persecution

in Albanian StudiesEternal bad governance or lack of government in Albania meant that education and scholarship lacked far behind the rest of Europe in the twentieth century. By the 1920s, however, with the spread of Albanian-language schools and with opportunities for education abroad, a new generation of educated Albanians arose, some of whom devoted themselves to research and scholarship in the field of Albanian studies. This first generation of scholars, active in the 1930s and early 1940s, was brutally eradicated when the communist partisans took over Albania in 1944. The terror and Stalinist purges that followed the takeover put an end to learning in Albania for many years. In this essay, Albanian linguist Kolec Topalli (b. 1938) traces the destruction of intellectual life in his country. He was himself one of the victims.

Class war and communist persecution affected all classes of Albanian society. They were particularly severe among intellectuals who had been educated abroad in the traditions of Western culture. The fear the communist regime had of democratic intellectuals who might have thought differently than what official dogma was to teach them, led to their persecution, arrest, internment, torture and execution and brought about a rupture, for half a century, of the intellectual ties the Albanians had with the civilised Western world. The following examples speak a clear language.

Donat Kurti (1903-1983)Bernardin Palaj (1894-1947) and Donat Kurti (1903-1983) unearthed our nation’s cultural treasures. The former was a well-known expert in mythology, whom Russian linguist Agnija Desnickaja (1912-1992) called “the man who knew the northern Albanian mountains best.” Palaj was also a poet and prose writer. Having graduated in Innsbruck in Austria, he worked as a teacher of ancient Greek and Latin at the Illyricum secondary school in Shkodra. He had been imprisoned in 1924, but devoted his whole life to Albanian studies. Learning from Shtjefën Gjeçovi in 1905 that “our mountains contain an inestimable treasure of Albanian epic songs,” he and Donat Kurti began their research, collecting, ordering and publishing hundreds of Songs of the Frontier Warriors (Kënge kreshnikësh) that were printed in the periodical Hylli i Dritës and were recognized as being among the best in the Balkans. His reward for this great achievement was imprisonment in 1946, and savage torture until his death in prison at the age of 50. One of his fellow prisoners reported: “They had tied his hands with rusty wire to a pine tree in the courtyard where he hung.” This was where the prisoners were usually beaten to death. Then they stuffed him into a rotting cell under a staircase. He spent months and months there until he got blood poisoning and died of tetanus. They buried him at the end of the courtyard, but his remains were never found. Palaj was accused of being a foreign agent even though it was he who gave the nation its most sacred gift, the epic songs that foreign scholars would rank among the greatest in Europe and compare to the Greek Iliad, the French Chanson de Roland and the German Nibelungen.

Donat Kurti, the Hans Christian Andersen of Albania, was an active collector of folklore. He graduated from San Antonio University in Rome with “doctor of science” degree and knew seven foreign languages. Norbert Jokl called him “one of the greatest Albanian prose writers.” Kurti was to suffer the same fate as his colleagues. He was imprisoned in the first years of the dictatorship and sentenced to death, a sentence that was later commuted to life in prison. Indeed he spent seventeen years in communist prisons and death camps. It is ironic that he died in complete obscurity, alone and forgotten, on the very day that a symposium was held in Tirana on the epic Songs of the Frontier Warriors.

Lazër Shantoja (1891-1945),

photo taken in Florence

in 1940.Another specialist in Albanian studies suffered an even worse fate. Lazër Shantoja (1891-1945) was a collector of folklore, a publicist, literary critic, poet and prose writer, and was a talented translator of Goethe, Schiller and Heine. He was very knowledgeable about Faust and William Tell. Shantoja had spent time in prison in the 1920s in the defence of democracy and was made to suffer appallingly under the dictatorship. He was arrested in February 1945 and was tortured so badly that he begged God to let him die. When his mother saw him for the last time, crawling in chains with gangrened legs, she pleaded with the guards to kill him and put an end to his suffering. A witch court sentenced him to death and he was shortly thereafter shot. The last person to see his mangled body stated: “They chopped him to bits. His arms and legs were mutilated. They had taken a saw to him. His right thigh was so swollen that it looked bigger than the rest of his body. The whole body was covered in wounds inflicted from all sorts of instruments. He could not stand up, so they executed him in an open grave in a hail of bullets. Stones and dirt were heaped on his mutilated body and his remains were never found.” Shantoja’s work, published in a range of periodicals of the period, was gathered in one 700-page volume sixty years after his death. He was known abroad, too. I was present at a scholarly gathering in Rome four years ago that was organized in his honour.

Nikollë Gazulli (1892-1946) was another scholar, intellectual and specialist in Albanian studies, who was executed in the first months of the communist takeover. He was the author of the best Albanian dialect dictionary, including rare words, and with a multitude of notes and explanations and an in-depth treatise on Albanian prefixes and suffixes. It is a veritable treasure of lexicography. Gazulli was also active in onomastic lexicography as the author of the first Albanian onomastic dictionary, published in the journal Hylli i Dritës. This work also involved history and ethnography. As far as we know, Gazulli had collected a further 2,000 terms, but this collection appears to have been lost. Despite this substantial contribution, his name was never referred to in Albanian studies. At the most, people were allowed to quote the title of his work and his initials, but never mention his name. This was because he was shot without trial in the early years of the communist regime. Besieged by a band of communists, he died a martyr in a cave where he had hidden from the Red terror, just as Bajram Curri had done years before him. Gazulli had already spent four years in prison in Gjirokastra in the 1930s and had been released thanks to the intervention of Norbert Jokl, Gjergj Fishta and Aleksandër Xhuvani. He died without a grave.

Another great collector of folklore, rare words, toponyms, historical information, mythology and legends etc. was Mark Dushi. He left several works in manuscript form in the Albanian State Archives, works which await the attention of some specialist to be published. One book of his that was published posthumously was Tirana dhe rrethinat e saj [Tirana and its Surroundings] that contains archaeological, ethnographic, linguistic and etymological data and information of scholarly interest about the Albanian capital and its surroundings. Despite all of his scholarly activities, he was imprisoned by the dictatorship, brutally tortured, sentenced to death and shot at the age of forty-six.

Many other scholars suffered a similar fate. They were sent to prison, interned, or otherwise persecuted. Mention must be made in this connection of three well-known Orientalists: Mykerem Janina, Vexhi Buharaja and Tahir Dizdari who were all experts in the old and modern languages of the Middle East, trained philologist, translators and transcribers of numerous scholarly works.

Mykerem Janina was one the best Albanian specialists in Ottoman studies, an expert in historical documents and palaeography, and was translator of the Defter of the Albanian Sanjak, published by Turkish historian Halil Inalcik. He began publishing in the 1930s. Janina was imprisoned twice under the stereotype charge of “agitation and propaganda” and spent fifteen years in prison and internment. The second term of imprisonment was handed down when he was almost eighty years old.

Vexhi Buharaja (1920-1987) left behind a extensive legacy of Ottoman documentary material, works of major significance to the study of Albanian history. He translated the oriental works of the Frashëri brothers into Albanian: the play Besa [The Pledge] by Sami Frashëri and Ëndërrimet [Reverie] by Naim Frashëri, as well as several masterpieces of Persian literature. He was an intellectual of great scholarly potential who worked for ten years at the Institute of History. In 1975, he was fired and spent the years of his greatest potential in solitude, away from scholarly work.

Tahir Dizdari (1900 - ca. 1975)Tahir Dizdari (1900-ca. 1975) is the author of the largest and best dictionary of oriental loanwords in Albanian, with explanations of Turkish loans, including their lexical, grammatical, ethnographic, literary and etymological background, as well as corresponding terms in the other languages of the Balkan Peninsula. It is a work of great value not only for Albanian studies, but also for Orientalists and Balkanists. However, the fruits of these years of dedication were not published in his lifetime, but 33 years after his death. The simple reason behind this was that Tahir Dizdari had been sent to jail in 1951 as an anti-communist, even though he had been interned by the fascists in 1939 for his patriotic and democratic sentiments.

Among others to suffer this fate were Hellenists, Latinists and translators whose only failing was that they had studied abroad and were not supportive of the dictatorship. Guljelm Deda spent fourteen years translating the 40,000 lines of rhymed verse of the Italian epic Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto into Albanian, and then spent much of the rest of his life in prison and internment. When he was released, he was given a job breaking rocks on Mount Tarabosh. Mark Dema, the talented translator of Virgil’s Aeneid, and Veniamin Dashi, translator of many works of Albanological interest from German, suffered a similar fate. They both served many years in prison and were later assigned to anonymity and oblivion. Mit’hat Arianiti also translated major works of Albanological interest from German, among which was the three-volume Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch [Indo-European Etymological Dictionary] of Julius Pokorny, a copy of which survived in a museum in Durrës. His only reward were years of prison and internment.

Mit’hat Araniti (1912-1992) translated major works of Albanian studies, but his work remained anonymous, even though the books in question are still being used for scholarly research today. He spent forty years translating lengthy volumes, dictionaries, and studies by early and contemporary authors from all the foreign languages he knew. It was he who made known the scholarly works of Mayer, Russu, Krahe, Stipčević, De Simone, Jokl, Praschniker, Walde, Hahn and Šufflay, thus providing Albanian scholars with an incomparable wealth of information on archaeology, numismatics, Illyriology and etymology, etc. Museums in Durrës and Tirana have in their possession over 250 manuscripts of works he translated. And what was his recompense? He was arrested with his father and brother in 1944, thus becoming one of the first victims of communist terror. Araniti spent ten years in prison and a further seven years in internment before he was released as an old man.

Another great translator of Classical literature was Gjon Shllaku, who translated major texts such as Homer’s Iliad, the works of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, Virgil’s Georgics and the French Chanson de Roland. In manuscript form, he left behind a “Latin-Albanian Dictionary” and a “Greek-Albanian Dictionary.” Shllaku spent several years in prison. Nikollë Dakaj, translator, linguist, poet, literary critic and folklore expert, spent several years in communist prisons and was then obliged to make a living slaving in a brick factory. It was thus in mud and among bricks that one could encounter the most talented figures of the period. This was the venue assigned by the dictatorship to those who insisted on conversing with Homer, Virgil, Dante or Petrarch, to those who had the misfortune of being educated in the West and to anyone dared to contradict official dogmas.

Mark Harapi (1890-1973) was another talented figure. He translated the famous Italian novel I promessi sposi [The Betrothed] of Alessandro Manzoni into Albanian. Harapi was a leading intellectual figure of his age and refused a teaching position at the University of Rome so that he could return to Albania. He was the first person to transcribe and comment the Cuneus Prophetarum [Band of the Prophets] of Pjetër Bogdani. Harapi was sentenced to twenty years in prison, and served ten, plus five further years in internment. He lived his final days as a beggar in the street where he had once made his home.

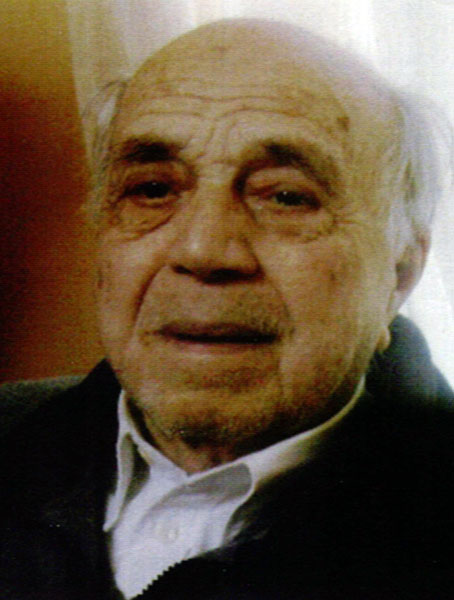

A similar fate was suffered by the last great translator of Classical literature, who died only recently. Pashko Gjeçi (1918-2010) translated about 40,000 lines of verse from ancient and modern literatures, giving us pure and crystalline Albanian versions of Homer’s Odyssey, Goethe’s Faust, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Racine’s Andromaque [Andromache], the poetry of Leopardi and Carducci and, above all, the three parts of Dante’s Divine Comedy, to which he devoted twenty years of his life. He was sentenced in the early years of the dictatorship and spent several years of horror in communist prisons and death camps, at the entrance of which one might well have inscribed Dante’s verse:

Pashko Gjeçi (1918-2010)

“Per me si va nella città dolente,

Per me si va nell’ eterno dolore,

Per me si va tra la perduta gente…

Lasciate ogni speranza voi, ch’entrate.”[Through me you pass into the city of woe:

Through me you pass into eternal pain:

Through me among the people lost for aye…

All hope abandon, ye who enter here.]Many of those who passed through into the prisons of Burrel and Spaç, or were sent to work in the swamps of Maliq and Beden, never got out, and gave up the ghost where they were.

Jusuf Vrioni (1916-2001) was another great translator, from and into French, who spent much of his life in communist prisons. He impressed even the French with his elegant translations, though he spent sixteen years of his life in prisons and death camps. When he got out, he left his good name behind him as he was not allowed to publish it in any book or journal. He had been sentenced to life in prison and it was only in 1958 that he was released from the small prison into the vast prison that was communist Albania. He remained an anonymous figure until the 1990s.

A further example of communist persecution was Fran Illia (1918-1997), a veritable second Shtjefën Gjeçovi, who paid for his passion for collecting customs, traditions and rare words of Albanian with a Calvary of pain. When he submitted his book “The Kanun of Scanderbeg” for publication, he was summoned, not to launch the book, but to be handcuffed and taken away. After seven months of torture in a cell of the Sigurimi (State Security) and a swift trial at a kangaroo court with all its cheering and jeering, he was sentenced to death, a penalty that was commuted to twenty-five years in prison. He did twenty of them.

Gjergj Fishta (1871-1940), the greatest figure of Albania literature, called the “Albanian Homer,” headed the 1908 commission that decided upon an Albanian alphabet. He was also among the members of the Literary Commission of the First World War. It was only his early death that saved him from the hell of communist death camps. It was hard for the communist authorities to delete all trace of the poet because his works had been published while he was still alive. They were well known and respected, and recited by Albanians throughout the country. As such, the authorities regarded him as a potential threat. Even though he was dead, they set about to persecute him and take macabre revenge upon him. His remains were found, dug up, and thrown into the River Drin. In other countries, the remains of national poets are preserved with respect as if they were holy relics, and are often the site of pilgrimages. Dante’s grave has been honoured in Ravenna for seven hundred years. Shakespeare’s grave in Stratford has been preserved for four hundred years. Even the grave of Jeronim De Rada in Macchia in the mountains of Calabria has been tended to for over a century now by the Arbëresh. These men had the good fate of not living under communism. Only in communist Albania could a national poet be left without a grave. It is not unknown for the bones of great men to be dug up and used as lucky charms, but only among the Albanians are such bones thrown into the river and lost forever. As they could not do Fishta any harm during his lifetime, they vented their rage on his literary works. It was made illegal to read, talk about or even possess his books. There are many known cases of intellectuals who were arrested for having read Fishta, for having spoken about him or for having possessed copies of The Highland Lute, etc. The dictatorship, a creation of the Slav communists, never forgave the poet for immortalizing the struggle of the Albanians: “Is it sign of all your culture that you parcel out Albania just to rear the cubs of Russia?” Fishta was never once mentioned as head of the commission that chose the Albanian alphabet. Because of his presence and the presence of a couple of other figures in the photographs taken of the commission at the 1908 Congress, these pictures were not shown to the Albanian public for half a century.

Viktor Volaj spent many years in internment camps. He was a linguist, lexicographer, and teacher of Albanian, Latin and Greek at the Illyricum secondary school in Shkodra. He was also the greatest critic and commentator of the works of Gjergj Fishta, on which he laboured for many years under the supervision of the great poet himself. For this reason, he is remembered as the “scholar without any publications.” Encouraged by Aleksander Xhuvani and Eqrem Çabej, Volaj collected and offered to the Linguistics Institute 1200 rare words and expressions of Albanian as a contribution to the Great Albanian Dictionary, but his name is mentioned nowhere as a contributor. He wrote several works of his own, but they were never published under the dictatorship and were eventually lost.

Nikollë Mazreku (1912-1996) was specialist in history, language and literature and one of the best scholars of Latin. He left behind many manuscripts, one of which was on the Albanian national hero, Scanderbeg. Mazreku collected rare words that he enjoyed using in his poetry. He was an ardent protagonist of the Albanian nation and its culture. He was given twenty-five years in prison and twelve years of internment.

Also imprisoned was Marin Sirdani (1887-1962), a historian, folklorist and writer. Sirdani collected legends, folksongs and sayings, and compiled rare expressions and toponyms. He was the author of Skanderbegu mbas gojëdhanash [Scanderbeg in oral tradition], Për historinë kombëtare [On national history], and Shqypnia e shqiptarëve [Albania of the Albanians]. Sirdani left several thousands of pages behind in manuscript form, results of half a century of devoted work, but they were burnt by the organs of the State Security.

His brother, Aleksandër Sirdani (1892-1948), another scholar and collector of folklore and rare Albanian words, also left behind thousands of pages in manuscript form. He was brutally tortured. His mutilated body was dragged through the town of Koplik to terrify the inhabitants. He was eventually put to death with a pitchfork and his body was thrown into a sewage pit.

Selman Riza (1909-1988),

photo from the 1940s.

Other scholars were cast into oblivion in other way. Their works were simply never published or read. Such was the fate of the great linguist Selman Riza (1909-1988), who devoted his whole life to Albanian studies. He had been interned by the fascists on the island of Ventotene for his defence of democracy and for the freedom of his country. He was then interned by the Tito regime in Yugoslavia for his struggle for a free Kosovo. Riza was harshly treated by the communist dictatorship in Tirana, having spent much time in prisons and internment, and having gone from one job to another. He was fired from the Linguistics Institute and was then interned in Berat. His unpublished works were ignored for years. Even the funeral of this giant of Albanian studies went unattended.

Such a fate was also suffered by the linguist Justin Rrota (1889-1964). No officials of the regime ever mentioned this author of numerous linguistic studies, this scholar who brought back to Albania a copy of the first Albanian-language book, the Missal of Gjon Buzuku. His death went unnoticed and his works were ignored for half a century in the archives of the Linguistics Institute. They were only published after the fall of the dictatorship and the restoration of democracy.

For fifty years, the names and works of the greatest figures of Albanian scholarship abroad were also covered over in silence: Martin Camaj, Namik Ressuli, Arshi Pipa, Karl Gurakuqi (1895-1971), Mustafa Kruja, Tajar Zavalani (1903-1966), Zef Valentini and others. Their very names were taboo under the communist regime.

Ernest Koliqi (1903-1975), poet and prose writer, translator and critic, scholar and publicist, professor of Albanian studies at La Sapienza University in Rome, was one of the most eminent figures of Albanian literature and culture of his day. In addition to his own literary works, he translated the great poets of Italy, such as Dante, Petrarch, Ariosto, Tasso, Parini, Monti and Foscolo. In addition, he translated some of the cantos of Fishta’s “The Highland Lute” from Albanian into Italian. Koliqi was also active collecting material in the field of folklore as well as with scholarly research, and played an active role in the publication of a number of cultural and scholarly periodicals. For instance, he was editor of the periodicals Shêjzat/Le Pleiadi, Illyria and Shkëndija, important for a transmission of information about the Albanian world. It was under his direction that the Studi Albanesi series was initiated. Koliqi was a noted stylist in his poetry and prose works, offering new syntactic structures and enriching the Albanian lexicon. He was the éminence grise of the emigrant community, the figure who kept Albanian studies and traditions alive in Italy, in particular among the Arbëresh. Although his work was well known abroad, it was stifled and kept in silence in Albania.

Martin Camaj (1925-1992) was one of the greatest figures of Albanian studies, and was, in addition, among the most talented Albanian writers and poets. In the field of scholarship, he left a series of works on the history of the Albanian language, on grammar and dialectology, on Arbëresh etymology and dialects, on early texts, folklore and literature. He was the main figure of Albanian emigration and one who kept studies on the Albanian language and traditions alive in Italy, Germany and elsewhere. The communist regime considered him a “traitor” simply because he had managed to escape from the Stalinist inferno to the free world, and yet he remained a true Albanian. It is as such that he has been remembered since his death. I had occasion to be at his graveside. It is a simple plot in the cemetery of Lenggries in Germany, an unpolished stone that his compatriots brought with them from the mountains of Dukagjin to place upon the resting spot of this great Albanian, who died before ever being able to revisit his homeland.

Another Albanologist who escaped from the barbed wire encircling Albania was Arshi Pipa (1920-1997), a specialist in linguistics, folklore, literary criticism, aesthetics, poetry and translation. He was arrested immediately after the communist takeover, but was able to escape prison and to flee abroad. Having emigrated to the United States, he taught at the university there, edited a number of scholarly and literary periodicals and published several books and articles of interest for Albanian culture. Up until the 1990s, no one in Albania dared mention his name, and none of his publications were known.

Namik Ressuli (1908-1985)

Namik Ressuli (1908-1985) was a philologist, grammarian, literary historian, scholar of ancient texts, and director of the Institute for Albanian Studies at La Sapienza University in Rome. He transcribed the “Songs of Milosao” of De Rada and other works of early Arbëresh and Albanian literature. The Grammatica Albanese [Grammar of Albanian] he published is among the best of its kind. His greatest achievement was the transcription, commentary and publication of the earliest book ever written in Albanian, the Missal of Gjon Buzuku. Many scholars had worked on this over the preceding decades, and ten years after Ressuli, Eqrem Çabej re-edited the work in Tirana. This Missal long remained unpublished in the archives of the Linguistics Institute because the authorities were suspicious of it as a “work of religious content.” The most recent publication on Buzuku is the 800-page Das albanische Verbalsystrem in der Sprache des Gjon Buzuku [The Albanian Verbal System in the Language of Gjon Buzuku] by Wilfried Fiedler, who relied on the work of Namik Ressuli. Even though Ressuli’s work had substantial impact in Albanian studies, his name was a taboo and his publications were kept in the National Library for half a century under the infamous letter “R”, meaning for “Reserved distribution.” He was never allowed to return to Albania.

Faik Konitza (1875-1942) made an important contribution to literary Albanian and to the Albanian question. In his periodical Albania he offered place for much discussion, debate in which he took part himself from time to time. He was quite rightly known as one of the most cultured men of his age. Although his writings assisted substantially in enriching the Albanian language, his name was not mentioned in public in Albania for half a century.

Mustafa Kruja (1887-1958) was a noted scholar of the Albanian language, a man with a broad education who left behind a number of manuscripts. He is known to have compiled a dictionary of Albanian, including etymological information, but no one knows what became of it. All trace of it was lost, as has been the case of many other works of scholarly and cultural research. However, one of his best studies was recently published, his Nji studim analitik: gjuha e Frang Bardhit dhe shqipja moderne [An Analytical Study: the Language of Frang Bardhi and Modern Albanian] which offers not only linguistic and historical analyses, but also an attempt to codify the Albanian language. His contribution to scholarship is seen not only in his linguistic studies, but also in his endeavours to create and maintain the Albania’s first scholarly institution, the Institute of Albanian Studies.

Zef Valentini (1900-1979) was another eminent specialist in Albanian studies, whose works were never recognized in communist Albania. He was an Albanian through and through, although he was not actually of Albanian blood. Valentini was an historian, ethnologist, linguist, literature professor, collaborator and editor of scholarly and literary periodicals in Albania and abroad, and a member of several scholarly academies. He had an excellent knowledge of the Albanian language, and of the history and ethnology of the country, and did much to promote the Albanian nation and its culture in the outside world. His works were seminal to Albanian studies. After his departure from Albania, he continued doing research and publishing in the field of Albanology at the University of Palermo, where headed the International Institute for Albanian Studies. Valentini accomplished the work of an entire institute. His greatest achievement, the Acta Albaniae Veneta, consists of 27 volumes of documents on mediaeval Albanian history. Although he spent all the rest of his life writing about our country, he was never allowed to visit it during the half a century of dictatorship. His name became taboo; no one was allowed to mention it. Though the communist regime was not able to imprison the scholar himself, who had left Albania one year before the rise of the dictatorship, it did keep his works in custody for half a century, placing them under the letter “R”.

In conclusion, one might ask: “What were all of these people actually guilty of?” Their guilt was no different from mine in 1949, when I was nine years old and the communist regime interned me in death camps surrounded by barbed wire in Turan and Bënça near Tepelena and in the fortress of Ali Pasha in Porto Palermo near Himara. Their guilt was no different from mine in 1990 when I was working as a village school teacher, far from my family, and the Sigurimi (State Security) placed my name on a death list – a document that was later published, after the fall of the regime.

It is said that a nation that ignores its history is condemned to repeat it. Let us never forget the national tragedy we suffered - the fifty years of communism that brought torture, crucifixion and martyrdom upon the entire nation.

[Persekutimi komunist në shkencat albanologjike, published in Hylli i Dritës, Shkodra, 1 (2010), p. 8-17. Translated from the Albanian by Robert Elsie.]

TOP